A Look at the History of Instrumental Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Science of String Instruments

The Science of String Instruments Thomas D. Rossing Editor The Science of String Instruments Editor Thomas D. Rossing Stanford University Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) Stanford, CA 94302-8180, USA [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4419-7109-8 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-7110-4 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-7110-4 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer ScienceþBusiness Media (www.springer.com) Contents 1 Introduction............................................................... 1 Thomas D. Rossing 2 Plucked Strings ........................................................... 11 Thomas D. Rossing 3 Guitars and Lutes ........................................................ 19 Thomas D. Rossing and Graham Caldersmith 4 Portuguese Guitar ........................................................ 47 Octavio Inacio 5 Banjo ...................................................................... 59 James Rae 6 Mandolin Family Instruments........................................... 77 David J. Cohen and Thomas D. Rossing 7 Psalteries and Zithers .................................................... 99 Andres Peekna and Thomas D. -

A Musical Instrument of Global Sounding Saadat Abdullayeva Doctor of Arts, Professor

Focusing on Azerbaijan A musical instrument of global sounding Saadat ABDULLAYEVA Doctor of Arts, Professor THE TAR IS PRObabLY THE MOST POPULAR MUSICAL INSTRUMENT AMONG “The trio”, 2005, Zakir Ahmadov, AZERbaIJANIS. ITS SHAPE, WHICH IS DIFFERENT FROM OTHER STRINGED INSTRU- bronze, 40x25x15 cm MENTS, IMMEDIATELY ATTRACTS ATTENTION. The juicy and colorful sounds to the lineup of mughams, and of a coming from the strings of the tar bass string that is used only for per- please the ear and captivate people. forming them. The wide range, lively It is certainly explained by the perfec- sounds, melodiousness, special reg- tion of the construction, specifically isters, the possibility of performing the presence of twisted steel and polyphonic chords, virtuoso passag- copper strings that convey all nuanc- es, lengthy dynamic sound rises and es of popular tunes and especially, attenuations, colorful decorations mughams. This is graphically proved and gradations of shades all allow by the presence on the instrument’s the tar to be used as a solo, accom- neck of five frets that correspondent panying, ensemble and orchestra 46 www.irs-az.com instrument. But nonetheless, the tar sounding board instead of a leather is a recognized instrument of solo sounding board contradict this con- mughams when the performer’s clusion. The double body and the mastery and the technical capa- leather sounding board are typical of bilities of the instrument manifest the geychek which, unlike the tar, has themselves in full. The tar conveys a short neck and a head folded back- the feelings, mood and dreams of a wards. Moreover, a bow is used play person especially vividly and fully dis- this instrument. -

CAPSTONE 20-1 SWA Field Study Trip Book Part II

CAPSTONE 20-1 SWA Field Study Trip Book Part II Subject Page Afghanistan ................................................................ CIA Summary ......................................................... 2 CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 3 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 24 Culture Gram .......................................................... 30 Kazakhstan ................................................................ CIA Summary ......................................................... 39 CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 40 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 58 Culture Gram .......................................................... 62 Uzbekistan ................................................................. CIA Summary ......................................................... 67 CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 68 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 86 Culture Gram .......................................................... 89 Tajikistan .................................................................... CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 99 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 117 Culture Gram .......................................................... 121 AFGHANISTAN GOVERNMENT ECONOMY Chief of State Economic Overview President of the Islamic Republic of recovering -

A Review of the Origin and Evolution of Uygur Musical Instruments

2019 International Conference on Humanities, Cultures, Arts and Design (ICHCAD 2019) A Review of the Origin and Evolution of Uygur Musical Instruments Xiaoling Wang, Xiaoling Wu Changji University Changji, Xinjiang, China Keywords: Uygur Musical Instruments, Origin, Evolution, Research Status Abstract: There Are Three Opinions about the Origin of Uygur Musical Instruments, and Four Opinions Should Be Exact. Due to Transliteration, the Same Musical Instrument Has Multiple Names, Which Makes It More Difficult to Study. So Far, the Origin of Some Musical Instruments is Difficult to Form a Conclusion, Which Needs to Be Further Explored by People with Lofty Ideals. 1. Introduction Uyghur Musical Instruments Have Various Origins and Clear Evolution Stages, But the Process is More Complex. I Think There Are Four Sources of Uygur Musical Instruments. One is the National Instrument, Two Are the Central Plains Instruments, Three Are Western Instruments, Four Are Indigenous Instruments. There Are Three Changes in the Development of Uygur Musical Instruments. Before the 10th Century, the Main Musical Instruments Were Reed Flute, Flute, Flute, Suona, Bronze Horn, Shell, Pottery Flute, Harp, Phoenix Head Harp, Kojixiang Pipa, Wuxian, Ruan Xian, Ruan Pipa, Cymbals, Bangling Bells, Pan, Hand Drum, Iron Drum, Waist Drum, Jiegu, Jilou Drum. At the Beginning of the 10th Century, on the Basis of the Original Instruments, Sattar, Tanbu, Rehwap, Aisi, Etc New Instruments Such as Thar, Zheng and Kalong. after the Middle of the 20th Century, There Were More Than 20 Kinds of Commonly Used Musical Instruments, Including Sattar, Trable, Jewap, Asitar, Kalong, Czech Republic, Utar, Nyi, Sunai, Kanai, Sapai, Balaman, Dapu, Narre, Sabai and Kashtahi (Dui Shi, or Chahchak), Which Can Be Divided into Four Categories: Choral, Membranous, Qiming and Ti Ming. -

Instrument List

Instrument List Africa: Europe: Kora, Domu, Begana, Mijwiz 1, Mijwiz 2, Arghul, Celtic & Wire Strung Harps, Mandolins, Zitter, Ewe drum collection, Udu drums, Doun Doun Collection of Recorders, Irish and other whistles, drums, Talking drums, Djembe, Mbira, Log drums, FDouble Flutes, Overtone Flutes, Sideblown Balafon, and many other African instruments. Flutes, Folk Flutes, Chanters and Bagpipes, Bodran, Hang drum, Jews harps, accordions, China: Alphorn and many other European instruments. Erhu, Guzheng, Pipa, Yuequin, Bawu, Di-Zi, Guanzi, Hulusi, Sheng, Suona, Xiao, Bo, Darangu Middle East: Lion Drum, Bianzhong, Temple bells & blocks, Oud, Santoor, Duduk, Maqrunah, Duff, Dumbek, Chinese gongs & cymbals, and various other Darabuka, Riqq, Zarb, Zills and other Middle Chinese instruments. Eastern instruments. India: North America: Sitar, Sarangi, Tambura, Electric Sitar, Small Banjo, Dulcimer, Zither, Washtub Bass, Native Zheng, Yuequin, Bansuris, Pungi Snake Charmer, Flute, Fife, Bottle Blows, Slide Whistle, Powwow Shenai, Indian Whistle, Harmonium, Tablas, Dafli, drum, Buffalo drum, Cherokee drum, Pueblo Damroo, Chimtas, Dhol, Manjeera, Mridangam, drum, Log drum, Washboard, Harmonicas Naal, Pakhawaj, Tamte, Tasha, Tavil, and many and more. other Indian instruments. Latin America: Japan: South American & Veracruz Harps, Guitarron, Taiko Drum collection, Koto, Shakuhachi, Quena, Tarka, Panpipes, Ocarinas, Steel Drums, Hichiriki, Sanshin, Shamisen, Knotweed Flute, Bandoneon, Berimbau, Bombo, Rain Stick, Okedo, Tebyoshi, Tsuzumi and other Japanese and an extensive Latin Percussion collection. instruments. Oceania & Australia: Other Asian Regions: Complete Jave & Bali Gamelan collections, Jobi Baba, Piri, Gopichand, Dan Tranh, Dan Ty Sulings, Ukeleles, Hawaiian Nose Flute, Ipu, Ba,Tangku Drum, Madal, Luo & Thai Gongs, Hawaiian percussion and more. Gedul, and more. www.garritan.com Garritan World Instruments Collection A complete world instruments collection The world instruments library contains hundreds of high-quality instruments from all corners of the globe. -

"Tal-Grixti" a Family of Żaqq and Tanbur Musicians

"TAL-GRIXTI" A FAMILY OF ŻAQQ AND TANBUR MUSICIANS Anna Borg Cardona, B.A., L.T.C.L. On his visit to Malta, George Percy Badger (1838) observed that Unative musical instruments", were "getting into disuse" (1). Amongst these was the Maltese bagpipe known as żaqq'. A hundred years later, the żaqq was stil1 in use, but evidently still considered to be waning. By the end of the first half of the twentieth century, the few remaining żaqq musicians were scattered around the isla:nd of Ma1ta in Naxxar, Mosta, Siġġiewi, Dingli, Żurrieq, Birgu (Vittoriosa), Marsa, Mellieħ.a and also on the sister island of Gozo, in Rabat. By the time Partridge and Jeal (2) investigated the situation between 1971 and 1973, they found a total of9living players in Malta and none in Gozo. Now the instrument is no longer played and may be considered virtually extinct. Zaqq players up to the early part of the twentieth century used to perform in the streets and in coffee or wine bars. They would often venture forth to nearby villages, making melodious music to the accompaniment of percussive instruments such as tambourine (tanbur) or fiiction drum (rabbaba, żuvżaJa). It was also not uncommon to witness a group of dancers c10sely followingthe musicians and contorting to their rhythms. This music came to be expected especially a.round Christmas time, Feast days (Festi) and Camival time. The few musicians known as żaqq players tended to pass theit knowledge on from generation to generation, in the same way as other arts, crafts and trades were handed down. -

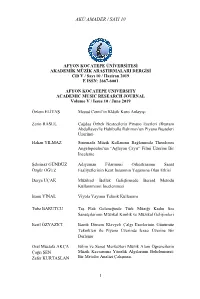

Akü Amader / Sayi 10 1

AKÜ AMADER / SAYI 10 AFYON KOCATEPE ÜNİVERSİTESİ AKADEMİK MÜZİK ARAŞTIRMALARI DERGİSİ Cilt V / Sayı 10 / Haziran 2019 E ISSN: 2667-6001 AFYON KOCATEPE UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC MUSIC RESEARCH JOURNAL Volume V / Issue 10 / June 2019 Özlem ELİTAŞ Mesud Cemil’in Klâsik Koro Anlayışı Zerin RASUL Çağdaş Özbek Bestecilerin Piyano Eserleri (Rustam Abdullayev'le Habibulla Rahimov'un Piyano Besteleri Üzerine) Hakan YILMAZ Sinemada Müzik Kullanımı Bağlamında Theodoros Angelopoulos’un “Ağlayan Çayır” Filmi Üzerine Bir İnceleme Şehrinaz GÜNDÜZ Adıyaman Filarmoni Orkestrasının Sanat Özgür OĞUZ Faaliyetlerinin Kent İnsanının Yaşamına Olan Etkisi Derya UÇAK Müziksel Bellek Geliştirmede Berard Metodu Kullanımının İncelenmesi Banu YİNAL Viyola Yayının Teknik Kullanımı Tuba BARUTCU Taş Plak Geleneğinde Türk Müziği Kadın Ses Sanatçılarının Müzikal Kimlik ve Müzikal Gelişimleri Beril ÖZYAZICI Barok Dönem Klavyeli Çalgı Eserlerinin Günümüz Teknikleri ile Piyano Üzerinde İcrası Üzerine Bir Derleme Oral Mustafa AKÇA Bilim ve Sanat Merkezleri Müzik Alanı Öğrencilerin Çağrı ŞEN Müzik Kavramına Yönelik Algılarının Belirlenmesi: Zafer KURTASLAN Bir Metafor Analizi Çalışması 1 AKÜ AMADER / SAYI 10 AFYON KOCATEPE ÜNİVERSİTESİ AKADEMİK MÜZİK ARAŞTIRMALARI DERGİSİ Cilt V / Sayı 10 / Haziran 2019 E ISSN: 2667-6001 AFYON KOCATEPE UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC MUSIC RESEARCH JOURNAL Volume V / Issue 10 / June 2019 Sahibi / Owner Afyon Kocatepe Üniversitesi adına Devlet Konservatuvarı Müdürü Prof. Dr. Uğur TÜRKMEN Editörler / Editors Prof. Dr. Uğur TÜRKMEN Dr. Öğr. Üyesi Duygu SÖKEZOĞLU ATILGAN Yardımcı Editörler / Co-Editorials Doç. Çağhan ADAR Dr. Öğr. Üyesi Safiye YAĞCI Öğr. Elm. Filiz YILDIZ Yayın Kurulu / Editorial Board Prof. Dr. Uğur TÜRKMEN Prof. Dr. Emel Funda TÜRKMEN Doç. Çağhan ADAR Doç. Servet YAŞAR Dr. Öğr. Üyesi Duygu SÖKEZOĞLU ATILGAN Dr. Öğr. Üyesi Sevgi TAŞ Dr. -

University of California Santa Cruz the Vietnamese Đàn

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ THE VIETNAMESE ĐÀN BẦU: A CULTURAL HISTORY OF AN INSTRUMENT IN DIASPORA A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in MUSIC by LISA BEEBE June 2017 The dissertation of Lisa Beebe is approved: _________________________________________________ Professor Tanya Merchant, Chair _________________________________________________ Professor Dard Neuman _________________________________________________ Jason Gibbs, PhD _____________________________________________________ Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Table of Contents List of Figures .............................................................................................................................................. v Chapter One. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 Geography: Vietnam ............................................................................................................................. 6 Historical and Political Context .................................................................................................... 10 Literature Review .............................................................................................................................. 17 Vietnamese Scholarship .............................................................................................................. 17 English Language Literature on Vietnamese Music -

About Two Types of Universalism in the Musical Instruments of the Kazakhs

Opción, Año 35, No. 88 (2019): 567-583 ISSN 1012-1587 / ISSNe: 2477-9385 About Two Types Of Universalism In The Musical Instruments Of The Kazakhs Saule Utegalieva1, Raushan Alsaitova2, Talgat Mykyshev3, Maksat Medeybek4, Slushash Ongarbayeva5 1Musicology and Composition Department, Kurmangazy Kazakh National сonservatory E-mail: [email protected] 2Zhetysu state University named after Ilyas Zhansugurov E-mail: [email protected] 3T.K. Zhurgenov Kazakh national academy of arts E-mail: [email protected] 4Kurmangazy Kazakh National Conservatory E-mail: [email protected] 5E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The aim of the study is to investigate common features and differences between musical cultures of nomadic and settled Turks in Kazakhstan via comparative qualitative research methods. As a result, Timbre-register variation is actively used in dombra music. The compositional form of the kui - buyn (link) and with using transposition - suggests a register differentiation of the musical space. In conclusion, the timbre-register principle of development should be taken into account in the analysis of instrumental samples (dombra kui –tokpe and shertpe) and vocal-instrumental music not only of the Kazakhs, but also of other Turkic peoples. Keywords: Dombra, Kyl-Kobyz, Chordophones, Pinch, Bow. Recibido: 06-01-2019 Aceptado: 28-03-2019 568 Saule Utegalieva et al. Opción, Año 35, No. 88 (2019): 567-583 Sobre Dos Tipos De Universalismo En Los Instrumentos Musicales De Los Kazajos Resumen El objetivo del estudio es investigar las características comunes y las diferencias entre las culturas musicales de los turcos nómadas y asentados en Kazajstán a través de métodos comparativos de investigación cualitativa. -

The Poetics of Persian Music

The Poetics of Persian Music: The Intimate Correlation between Prosody and Persian Classical Music by Farzad Amoozegar-Fassie B.A., The University of Toronto, 2008 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Music) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) August 2010 © Farzad Amoozegar-Fassie, 2010 Abstract Throughout most historical narratives and descriptions of Persian arts, poetry has had a profound influence on the development and preservation of Persian classical music, in particularly after the emergence of Islam in Iran. A Persian poetic structure consists of two parts: the form (its fundamental rhythmic structure, or prosody) and the content (the message that a poem conveys to its audience, or theme). As the practice of using rhythmic cycles—once prominent in Iran— deteriorated, prosody took its place as the source of rhythmic organization and inspiration. The recognition and reliance on poetry was especially evident amongst Iranian musicians, who by the time of Islamic rule had been banished from the public sphere due to the sinful socio-religious outlook placed on music. As the musicians’ dependency on prosody steadily grew stronger, poetry became the preserver, and, to a great extent, the foundation of Persian music’s oral tradition. While poetry has always been a significant part of any performance of Iranian classical music, little attention has been paid to the vitality of Persian/Arabic prosody as its main rhythmic basis. Poetic prosody is the rhythmic foundation of the Persian repertoire the radif, and as such it makes possible the development, memorization, expansion, and creation of the complex rhythmic and melodic compositions during the art of improvisation. -

Further Reading, Listening, and Viewing

The Music of Central Asia: Further Reading, Listening, and Viewing The editors welcome additions, updates, and corrections to this compilation of resources on Central Asian Music. Please submit bibliographic/discographic information, following the format for the relevant section below, to: [email protected]. Titles in languages other than English, French, and German should be translated into English. Titles in languages written in a non-Roman script should be transliterated using the American Library Association-Library of Congress Romanization Tables: Transliteration Schemes for Non-Roman Scripts, available at: http://www.loc.gov/catdir/cpso/roman.html Print Materials and Websites 1. Anthropology of Central Asia 2. Central Asian History 3. Music in Central Asia (General) 4. Musical Instruments 5. Music, Sound, and Spirituality 6. Oral Tradition and Epics of Central Asia 7. Contemporary Music: Pop, Tradition-Based, Avant-Garde, and Hybrid Styles 8. Musical Diaspora Communities 9. Women in Central Asian Music 10. Music of Nomadic and Historically Nomadic People (a) General (b) Karakalpak (c) Kazakh (d) Kyrgyz (e) Turkmen 11. Music in Sedentary Cultures of Central Asia (a) Afghanistan (b) Azerbaijan (c) Badakhshan (d) Bukhara (e) Tajik and Uzbek Maqom and Art Song (f) Uzbekistan (g) Tajikistan (h) Uyghur Muqam and Epic Traditions Audio and Video Recordings 1. General 2. Afghanistan 3. Azerbaijan 4. Badakhshan 5. Karakalpak 6. Kazakh 7. Kyrgyz 8. Tajik and Uzbek Maqom and Art Song 9. Tajikistan 10. Turkmenistan 11. Uyghur 12. Uzbekistan 13. Uzbek pop 1. Anthropology of Central Asia Eickelman, Dale F. The Middle East and Central Asia: An Anthropological Approach, 4th ed. Pearson, 2001. -

The Bandistan Ensemble, Music from Central Asia

Asia Society and CEC Arts Link Present The Bandistan Ensemble, Music From Central Asia Thursday, July 14, 7:00 P.M. Asia Society 725 Park Avenue at 70th Street New York City Bandistan Ensemble Music Leaders: Alibek Kabdurakhmanov, Jakhongir Shukur, Jeremy Thal Kerez Berikova (Kyrgyzstan), viola, kyl-kiyak, komuz, metal and wooden jaw harps Emilbek Ishenbek Uulu (Kyrgyzstan), komuz, kyl-kiyak Alibek Kabdurakhmanov (Uzbekistan), doira, percussion Tokzhan Karatai (Kazakhstan), qyl-qobyz Sanjar Nafikov (Uzbekistan), piano, electric keyboard Aisaana Omorova (Kyrgyzstan), komuz, metal and wooden jaw harps Jakhongir Shukur (Uzbekistan), tanbur Ravshan Tukhtamishev (Uzbekistan), chang, santur Lemara Yakubova (Uzbekistan), violin Askat Zhetigen Uulu (Kyrgyzstan), komuz, metal jaw harp The Bandistan Ensemble is the most recent manifestation of an adventurous two-year project called Playing Together: Sharing Central Asian Musical Heritage, which supports training, artistic exchange, and career enhancement for talented young musicians from Central Asia who are seeking links between their own musical heritage and contemporary languages of art. The ensemble’s creative search is inspired by one of the universal axioms of artistic avant-gardes: that tradition can serve as an invaluable compass for exploring new forms of artistic consciousness and creativity inspired, but not constrained, by the past. Generously supported by the United States Department of State’s Bureau of South and Central Asian Affairs, Playing Together was established and has been