English Society 1660±1832

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Professionalisation of the Royal Navy: 1660-1688

The Professionalisation of the Royal Navy: 1660-1688 by Samantha Middleton The thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY of the University of Portsmouth September 2020 Abstract This thesis analyses the developments made between 1660 and 1688 that contributed towards the Royal Navy becoming a more professionalised organisation. It outlines the impact of individuals and their methods towards achieving professionalisation. The political and financial problems facing the navy before the restoration of the monarchy are also addressed. Biographical case studies of three influential naval reformers; James Stewart, The Duke of York; William Coventry; and Samuel Pepys are used to demonstrate the significant influence that they had on the process of professionalization. This thesis ascertains that although the terminology had not been invented at this stage, the principles of Management Control were implemented by Pepys, Coventry and the Duke of York as a method of organizational professionalisation, identifying examples of performance measurement, rewards systems and the implantation of standard operating procedures. An in-depth analysis of the Duke of York’s instructions for the duties of the Principal Officers demonstrates that the Duke of York introduced enhanced accounting procedures and additional control mechanisms to reduce abuses and increase administrative efficiency. Additionally, a set of professional responsibilities has been created within this thesis for Coventry, whose role as secretary is absent from the instructions. This shows for the first time, that Coventry identified his professional remit as focusing primarily on retrenchment and the reduction of abuses. This contributed towards wider professionalisation. -

Empire and English Nationalismn

Nations and Nationalism 12 (1), 2006, 1–13. r ASEN 2006 Empire and English nationalismn KRISHAN KUMAR Department of Sociology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, USA Empire and nation: foes or friends? It is more than pious tribute to the great scholar whom we commemorate today that makes me begin with Ernest Gellner. For Gellner’s influential thinking on nationalism, and specifically of its modernity, is central to the question I wish to consider, the relation between nation and empire, and between imperial and national identity. For Gellner, as for many other commentators, nation and empire were and are antithetical. The great empires of the past belonged to the species of the ‘agro-literate’ society, whose central fact is that ‘almost everything in it militates against the definition of political units in terms of cultural bound- aries’ (Gellner 1983: 11; see also Gellner 1998: 14–24). Power and culture go their separate ways. The political form of empire encloses a vastly differ- entiated and internally hierarchical society in which the cosmopolitan culture of the rulers differs sharply from the myriad local cultures of the subordinate strata. Modern empires, such as the Soviet empire, continue this pattern of disjuncture between the dominant culture of the elites and the national or ethnic cultures of the constituent parts. Nationalism, argues Gellner, closes the gap. It insists that the only legitimate political unit is one in which rulers and ruled share the same culture. Its ideal is one state, one culture. Or, to put it another way, its ideal is the national or the ‘nation-state’, since it conceives of the nation essentially in terms of a shared culture linking all members. -

Emigration from Great Britain

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: International Migrations, Volume II: Interpretations Volume Author/Editor: Walter F. Willcox, editor Volume Publisher: NBER Volume ISBN: 0-87014-017-5 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/will31-1 Publication Date: 1931 Chapter Title: Emigration from Great Britain Chapter Author: C. E. Snow Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c5111 Chapter pages in book: (p. 237 - 260) PART III STUDIES OF NATIONALEMIGRATION CURRENTS CHAPTER IX EMIGRATION FROM GREAT BRITAIN.' By DR. C. E. SNOW. General Concerning emigration from Great Britain prior to 1815, only fragmentary statistics are available, for before that date no regular attempt was made to measure the outflow of population.For some years before the treaty of peace with France, under which Canada in 1763 became a colony of the United Kingdom, a certain number of emigrants from Great Britain to the British North Amer- ican colonies were reported, but no reliable figures are available. During the five years 1769—1774 there was an emigration, probably approaching 10,000 persons per annum,2 from Scotland to North America, and substantial numbers also left England for the same destination.It has been estimated by Johnson3 that during the first decade of the nineteenth century the annual emigration from the whole of the United Kingdom to the American Continent ex- ceeded 20,000 persons, the majority going from the Highlands of Scotland and from Ireland. Emigration can be considered from two distinct aspects: (a) from the point of view of the force attracting people to other countries; (b) from the point of view of the force expelling people from their own country. -

H 955 Great Britain

Great Britain H 955 BACKGROUND: The heading Great Britain is used in both descriptive and subject cataloging as the conventional form for the United Kingdom, which comprises England, Northern Ireland, Scotland, and Wales. This instruction sheet describes the usage of Great Britain, in contrast to England, as a subject heading. It also describes the usage of Great Britain, England, Northern Ireland, Scotland, and Wales as geographic subdivisions. 1. Great Britain vs. England as a subject heading. In general assign the subject heading Great Britain, with topical and/or form subdivisions, as appropriate, to works about the United Kingdom as a whole. Assign England, with appropriate subdivision(s), to works limited to that country. Exception: Do not use the subdivisions BHistory or BPolitics and government under England. For a work on the history, politics, or government of England, assign the heading Great Britain, subdivided as required for the work. References in the subject authority file reflect this practice. Use the subdivision BForeign relations under England only in the restricted sense described in the scope note under EnglandBForeign relations in the subject authority file. 2. Geographic subdivision. a. Great Britain. Assign Great Britain directly after topics for works that discuss the topic in relation to Great Britain as a whole. Example: Title: History of the British theatre. 650 #0 $a Theater $z Great Britain $x History. b. England, Scotland, Northern Ireland, and Wales. Assign England, Scotland, Northern Ireland, or Wales directly after topics for works that limit their discussion to the topic in relation to one of the four constituent countries of Great Britain. -

Writing Another Continent's History: the British and Pre-Colonial Africa

eSharp Historical Perspectives Writing Another Continent’s History: The British and Pre-colonial Africa, 1880-1939 Christopher Prior (Durham University) Tales of Britons striding purposefully through the jungles and across the arid deserts of Africa captivated the metropolitan reading public throughout the nineteenth century. This interest only increased with time, and by the last quarter of the century a corpus of heroes both real and fictional, be they missionaries, explorers, traders, or early officials, was formalized (for example, see Johnson, 1982). While, for instance, the travel narratives of Burton, Speke, and other famous Victorians remained perennially popular, a greater number of works that emerged following the ‘Scramble for Africa’ began to put such endeavours into wider historical context. In contrast to the sustained attention that recent studies have paid to Victorian fiction and travel literature (for example, Brantlinger, 1988; Franey, 2003), such histories have remained relatively neglected. Therefore, this paper seeks to examine the way that British historians, writing between the Scramble and the eve of the Second World War, represented Africa. It is often asserted that the British enthused about much of Africa’s past. It is claimed that there was an admiration for a simplified, pre-modern existence, in keeping with a Rousseauean conception of the ‘noble savage.’ Some, particularly postcolonialists such as Homi Bhabha, have argued that this all added a sense of disquiet to imperialist proceedings. Bhabha claims that a colonizing power advocates a ‘colonial mimicry’, that is, it wants those it ruled over to become a ‘reformed, recognizable Other, as a subject of difference that is almost the same, but not quite’. -

Praise, Patronage, and the Penshurst Poems: from Jonson (1616) to Southey (1799)

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2015-09-24 Praise, Patronage, and the Penshurst Poems: From Jonson (1616) to Southey (1799) Gray, Moorea Gray, M. (2015). Praise, Patronage, and the Penshurst Poems: From Jonson (1616) to Southey (1799) (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/27395 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/2486 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Praise, Patronage, and the Penshurst Poems: From Jonson (1616) to Southey (1799) by Mooréa Gray A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN ENGLISH CALGARY, ALBERTA SePtember, 2015 © Mooréa Gray 2015 Abstract The Penshurst grouP of Poems (1616-1799) is a collection of twelve Poems— beginning with Ben Jonson’s country-house Poem “To Penshurst”—which praises the ancient estate of Penshurst and the eminent Sidney family. Although praise is a constant theme, only the first five Poems Praise the resPective Patron and lord of Penshurst, while the remaining Poems Praise the exemplary Sidneys of bygone days, including Sir Philip and Dorothy (Sacharissa) Sidney. This shift in praise coincides with and is largely due to the gradual shift in literary economy: from the Patronage system to the literary marketPlace. -

Background, Brexit, and Relations with the United States

The United Kingdom: Background, Brexit, and Relations with the United States Updated April 16, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL33105 SUMMARY RL33105 The United Kingdom: Background, Brexit, and April 16, 2021 Relations with the United States Derek E. Mix Many U.S. officials and Members of Congress view the United Kingdom (UK) as the United Specialist in European States’ closest and most reliable ally. This perception stems from a combination of factors, Affairs including a sense of shared history, values, and culture; a large and mutually beneficial economic relationship; and extensive cooperation on foreign policy and security issues. The UK’s January 2020 withdrawal from the European Union (EU), often referred to as Brexit, is likely to change its international role and outlook in ways that affect U.S.-UK relations. Conservative Party Leads UK Government The government of the UK is led by Prime Minister Boris Johnson of the Conservative Party. Brexit has dominated UK domestic politics since the 2016 referendum on whether to leave the EU. In an early election held in December 2019—called in order to break a political deadlock over how and when the UK would exit the EU—the Conservative Party secured a sizeable parliamentary majority, winning 365 seats in the 650-seat House of Commons. The election results paved the way for Parliament’s approval of a withdrawal agreement negotiated between Johnson’s government and the EU. UK Is Out of the EU, Concludes Trade and Cooperation Agreement On January 31, 2020, the UK’s 47-year EU membership came to an end. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 46100 I I

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again - beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Palaeoecological, Archaeological and Historical Data and the Making of Devon Landscapes

bs_bs_banner Palaeoecological, archaeological and historical data and the making of Devon landscapes. I. The Blackdown Hills ANTONY G. BROWN, CHARLOTTE HAWKINS, LUCY RYDER, SEAN HAWKEN, FRANCES GRIFFITH AND JACKIE HATTON Brown, A. G., Hawkins, C., Ryder, L., Hawken, S., Griffith, F. & Hatton, J.: Palaeoecological, archaeological and historical data and the making of Devon landscapes. I. The Blackdown Hills. Boreas. 10.1111/bor.12074. ISSN 0300-9483. This paper presents the first systematic study of the vegetation history of a range of low hills in SW England, UK, lying between more researched fenlands and uplands. After the palaeoecological sites were located bespoke archaeological, historical and documentary studies of the surrounding landscape were undertaken specifically to inform palynological interpretation at each site. The region has a distinctive archaeology with late Mesolithic tool scatters, some evidence of early Neolithic agriculture, many Bronze Age funerary monuments and Romano- British iron-working. Historical studies have suggested that the present landscape pattern is largely early Medi- eval. However, the pollen evidence suggests a significantly different Holocene vegetation history in comparison with other areas in lowland England, with evidence of incomplete forest clearance in later-Prehistory (Bronze−Iron Age). Woodland persistence on steep, but poorly drained, slopes, was probably due to the unsuit- ability of these areas for mixed farming. Instead they may have been under woodland management (e.g. coppicing) associated with the iron-working industry. Data from two of the sites also suggest that later Iron Age and Romano-British impact may have been geographically restricted. The documented Medieval land manage- ment that maintained the patchwork of small fields, woods and heathlands had its origins in later Prehistory, but there is also evidence of landscape change in the 6th–9th centuries AD. -

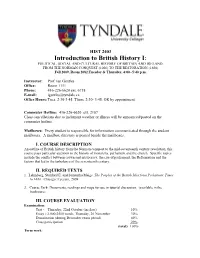

Introduction to British History I

HIST 2403 Introduction to British History I: POLITICAL, SOCIAL AND CULTURAL HISTORY OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND, FROM THE NORMAN CONQUEST (1066) TO THE RESTORATION (1660) Fall 2009, Room 2082,Tuesday & Thursday, 4:00--5:40 p.m. Instructor: Prof. Ian Gentles Office: Room 1111 Phone: 416-226-6620 ext. 6718 E-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Tues. 2:30-3:45, Thurs. 2:30- 3:45, OR by appointment Commuter Hotline: 416-226-6620 ext. 2187 Class cancellations due to inclement weather or illness will be announced/posted on the commuter hotline. Mailboxes: Every student is responsible for information communicated through the student mailboxes. A mailbox directory is posted beside the mailboxes. I. COURSE DESCRIPTION An outline of British history from the Norman conquest to the mid-seventeenth century revolution, this course pays particular attention to the history of monarchy, parliament and the church. Specific topics include the conflict between crown and aristocracy, the rise of parliament, the Reformation and the factors that led to the turbulence of the seventeenth century. II. REQUIRED TEXTS 1. Lehmberg, Stanford E. and Samantha Meigs. The Peoples of the British Isles from Prehistoric Times to 1688 . Chicago: Lyceum, 2009 2. Course Pack: Documents, readings and maps for use in tutorial discussion. (available in the bookstore) III. COURSE EVALUATION Examination : Test - Thursday, 22nd October (in class) 10% Essay - 2,000-2500 words, Thursday, 26 November 30% Examination (during December exam period) 40% Class participation 20% (total) 100% Term work : a. You are expected to attend the tutorials, preparing for them through the lectures and through assigned reading. -

The Pattern of Social Transformation in England Perkin, Harold

www.ssoar.info The pattern of social transformation in England Perkin, Harold Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Sammelwerksbeitrag / collection article Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: GESIS - Leibniz-Institut für Sozialwissenschaften Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Perkin, H. (1982). The pattern of social transformation in England. In K. H. Jarausch (Ed.), The transformation of higher learning 1860-1930 : expansion, diversification, social opening and professionalization in England, Germany, Russia and the United States (pp. 207-218). Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-339634 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under Deposit Licence (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, non- Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, transferable, individual and limited right to using this document. persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses This document is solely intended for your personal, non- Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für commercial use. All of the copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke By using this particular document, you accept the above-stated vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder conditions of use. -

A History of English Literature MICHAEL ALEXANDER

A History of English Literature MICHAEL ALEXANDER [p. iv] © Michael Alexander 2000 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W 1 P 0LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2000 by MACMILLAN PRESS LTD Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and London Companies and representatives throughout the world ISBN 0-333-91397-3 hardcover ISBN 0-333-67226-7 paperback A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 O1 00 Typeset by Footnote Graphics, Warminster, Wilts Printed in Great Britain by Antony Rowe Ltd, Chippenham, Wilts [p. v] Contents Acknowledgements The harvest of literacy Preface Further reading Abbreviations 2 Middle English Literature: 1066-1500 Introduction The new writing Literary history Handwriting