Palaeoecological, Archaeological and Historical Data and the Making of Devon Landscapes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mill Cottage the Mill Cottage Cockercombe, Over Stowey, Bridgwater, TA5 1HJ Taunton 8 Miles

The Mill Cottage The Mill Cottage Cockercombe, Over Stowey, Bridgwater, TA5 1HJ Taunton 8 Miles • 4.2 Acres • Stable Yard • Mill Leat & Stream • Parkland and Distant views • 3 Reception Rooms • Kitchen & Utility • 3 Bedrooms (Master En-Suite) • Garden Office Guide price £650,000 Situation The Mill Cottage is situated in the picturesque hamlet of Cockercombe, within the Quantock Hills, England's first Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. This is a very attractive part of Somerset, renowned for its beauty, with excellent riding, walking and other country pursuits. There is an abundance of footpaths and bridleways. The village of Nether Stowey is 2 miles away and Kingston St A charming Grade II Listed cottage with yard, stabling, 4.2 Acres of Mary is 5 miles away. Taunton, the County Town of Somerset, is some 8 miles to the South. Nether Stowey is an attractive centre land and direct access to the Quantock Hills. with an extensive range of local facilities, which are further supplemented by the town of Bridgwater, some 8 miles to the East. Taunton has a wide range of facilities including a theatre, county cricket ground and racecourse. Taunton is well located for national communications, with the M5 motorway at Junction 25 and there is an excellent intercity rail service to London Paddington (an hour and forty minutes). The beautiful coastline at Kilve is within 15 minutes drive. Access to Exmoor and the scenic North Somerset coast is via the A39 or through the many country roads in the area. The Mill Cottage is in a wonderful private location in a quiet lane, with clear views over rolling countryside. -

River Brue's Historic Bridges by David Jury

River Brue’s Historic Bridges By David Jury The River Brue’s Historic Bridges In his book "Bridges of Britain" Geoffrey Wright writes: "Most bridges are fascinating, many are beautiful, particularly those spanning rivers in naturally attractive settings. The graceful curves and rhythms of arches, the texture of stone, the cold hardness of iron, the stark simplicity of iron, form constant contrasts with the living fluidity of the water which flows beneath." I cannot add anything to that – it is exactly what I see and feel when walking the rivers of Somerset and discover such a bridge. From source to sea there are 58 bridges that span the River Brue, they range from the simple plank bridge to the enormity of the structures that carry the M5 Motorway. This article will look at the history behind some of those bridges. From the river’s source the first bridge of note is Church Bridge in South Brewham, with it’s downstream arch straddling the river between two buildings. Figure 1 - Church Bridge South Brewham The existing bridge is circa 18th century but there was a bridge recorded here in 1258. Reaching Bruton, we find Church Bridge described by John Leland in 1525 as the " Est Bridge of 3 Archys of Stone", so not dissimilar to what we have today, but in 1757 the bridge was much narrower “barely wide enough for a carriage” and was widened on the east side sometime in the early part of the 19th century. Figure 2 - Church Bridge Bruton Close by we find that wonderful medieval Bow Bridge or Packhorse Bridge constructed in the 15th century with its graceful slightly pointed chamfered arch. -

Writing Another Continent's History: the British and Pre-Colonial Africa

eSharp Historical Perspectives Writing Another Continent’s History: The British and Pre-colonial Africa, 1880-1939 Christopher Prior (Durham University) Tales of Britons striding purposefully through the jungles and across the arid deserts of Africa captivated the metropolitan reading public throughout the nineteenth century. This interest only increased with time, and by the last quarter of the century a corpus of heroes both real and fictional, be they missionaries, explorers, traders, or early officials, was formalized (for example, see Johnson, 1982). While, for instance, the travel narratives of Burton, Speke, and other famous Victorians remained perennially popular, a greater number of works that emerged following the ‘Scramble for Africa’ began to put such endeavours into wider historical context. In contrast to the sustained attention that recent studies have paid to Victorian fiction and travel literature (for example, Brantlinger, 1988; Franey, 2003), such histories have remained relatively neglected. Therefore, this paper seeks to examine the way that British historians, writing between the Scramble and the eve of the Second World War, represented Africa. It is often asserted that the British enthused about much of Africa’s past. It is claimed that there was an admiration for a simplified, pre-modern existence, in keeping with a Rousseauean conception of the ‘noble savage.’ Some, particularly postcolonialists such as Homi Bhabha, have argued that this all added a sense of disquiet to imperialist proceedings. Bhabha claims that a colonizing power advocates a ‘colonial mimicry’, that is, it wants those it ruled over to become a ‘reformed, recognizable Other, as a subject of difference that is almost the same, but not quite’. -

Langport and Frog Lane

English Heritage Extensive Urban Survey An archaeological assessment of Langport and Frog Lane Miranda Richardson Jane Murray Corporate Director Culture and Heritage Directorate Somerset County Council County Hall TAUNTON Somerset TA1 4DY 2003 SOMERSET EXTENSIVE URBAN SURVEY LANGPORT AND FROG LANE ARCHAEOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT by Miranda Richardson CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................... .................................. 3 II. MAJOR SOURCES ............................... ................................... 3 1. Primary documents ............................ ................................ 3 2. Local histories .............................. .................................. 3 3. Maps ......................................... ............................... 3 III. A BRIEF HISTORY OF LANGPORT . .................................. 3 IV. THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF LANGPORT . .............................. 4 1. PREHISTORIC and ROMAN ........................ ............................ 4 2. SAXON ........................................ .............................. 7 3. MEDIEVAL ..................................... ............................. 9 4. POST-MEDIEVAL ................................ ........................... 14 5. INDUSTRIAL (LATE 18TH AND 19TH CENTURY) . .......................... 15 6. 20TH CENTURY ................................. ............................ 18 V. THE POTENTIAL OF LANGPORT . ............................... 19 1. Research interests........................... ................................. -

Se,Veri\ E.Stuary Levels

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE The Historic Landscapes of the Severn Estuary Levels AUTHORS Rippon, Stephen DEPOSITED IN ORE 25 April 2008 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10036/24173 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication Archaeology-in theSevern Estuary 11 (2000),1i9-i35 THE HISTORIC LANDSCAPES OF THE SE,VERI\E.STUARY LEVELS By StephenRippon The deepalluvial sequencesthat make up the SevernEstuary Levels comprisea seriesof stratified landscapesdating Jrom earlyprehi,story through to thepresent day. Most of theselandscapes are deeply buried, and, whilst exceptionally 'historic well-preserved,are largely inaccessibleand so ill-understood.It is only with the landscape',that lies on the surface of the Levels, that we can really start to reconstruct and analyse what thesepast landscapeswere like. However, although the enormously diverse historic landscapeis itself an important source of information, itsfull potential is only achievedthrough its integration with associatedarchaeological and documentatyevidence. This presentsmany challengesand whilst much has beenachieved in the last tenyears, there is a long way to go before we can write a comprehensivehistory of the SevernLevels. Two techniquesare vital. Historic landscapecharacterisation focuses on the key character -

English Society 1660±1832

ENGLISH SOCIETY 1660±1832 Religion, ideology and politics during the ancien regime J. C. D. CLARK published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, UK www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011±4211, USA www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia Ruiz de AlarcoÂn 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain # Cambridge University Press 2000 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published as English Society 1688±1832,1985. Second edition, published as English Society 1660±1832 ®rst published 2000. Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Baskerville 11/12.5 pt. System 3b2[ce] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data Clark, J. C. D. English society, 1660±1832 : religion, ideology, and politics during the ancien regime/J.C.D.Clark. p. cm. Rev. edn of: English society, 1688±1832. 1985. Includes index. isbn 0 521 66180 3 (hbk) ± isbn 0 521 66627 9 (pbk) 1. Great Britain ± Politics and government ± 1660±1714. 2. Great Britain ± Politics and government ± 18th century. 3. Great Britain ± Politics and government ± 1800±1837. 4. Great Britain ± Social conditions. i.Title. ii.Clark,J.C.D.Englishsociety,1688±1832. -

Neolithic Report

RESEARCH DEPARTMENT REPORT SERIES no. 29-2011 ISSN 1749-8775 REVIEW OF ANIMAL REMAINS FROM THE NEOLITHIC AND EARLY BRONZE AGE OF SOUTHERN BRITAIN (4000 BC – 1500 BC) ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES REPORT Dale Serjeantson ARCHAEOLOGICAL SCIENCE Research Department Report Series 29-2011 REVIEW OF ANIMAL REMAINS FROM THE NEOLITHIC AND EARLY BRONZE AGE OF SOUTHERN BRITAIN (4000 BC – 1500 BC) Dale Serjeantson © English Heritage ISSN 1749-8775 The Research Department Report Series, incorporates reports from all the specialist teams within the English Heritage Research Department: Archaeological Science; Archaeological Archives; Historic Interiors Research and Conservation; Archaeological Projects; Aerial Survey and Investigation; Archaeological Survey and Investigation; Architectural Investigation; Imaging, Graphics and Survey; and the Survey of London. It replaces the former Centre for Archaeology Reports Series, the Archaeological Investigation Report Series, and the Architectural Investigation Report Series. Many of these are interim reports which make available the results of specialist investigations in advance of full publication. They are not usually subject to external refereeing, and their conclusions may sometimes have to be modified in the light of information not available at the time of the investigation. Where no final project report is available, readers are advised to consult the author before citing these reports in any publication. Opinions expressed in Research Department Reports are those of the author(s) and are not necessarily those of English Heritage. Requests for further hard copies, after the initial print run, can be made by emailing: [email protected]. or by writing to English Heritage, Fort Cumberland, Fort Cumberland Road, Eastney, Portsmouth PO4 9LD Please note that a charge will be made to cover printing and postage. -

Two Aspects of the Windmill Hill Culture 1 Are to Be Discussed in This Paper

r. F. SMITH WINDMILL HILL AND ITS IMPLICATIONS (Figs. 1-2) Two aspects of the Windmill Hill culture 1 are to be discussed in this paper. One will be the specificproblem of the function of the causewayed enclosures or 'camps' which constitute one of its characteristic earthwork structures. The other will be its role as the founder of traditions that were to survive long after its own disappea rance. THE FUNCTION OF THE CAUSE WAYED ENCLOSURES Fifteen or sixteen earthworks of this type are now known in southerri England2, and over a dozen more may be indicated by cropmarks discovered during recent aerial surveys of valley gravels in counties north of the Thames (St. Joseph, 1966; see also Feachem, 1966). These, however, remain to be verified by excavation. The main concentration of proven sites therefore still lies in the counties of DOl'set, Wiltshire and Sussex, where there are altogether eleven, all on chalk downland; two more are in the Thames valley, in Berkshire and Middlesex, and the remainder are outliers in Bedfordshire and Devonshire. The enclosures3 are oval or roughly circular in plan and vary in diameter from about 400 m(Windmill Hill, Maiden Castle) to less than 200 m(Combe Hill, Staines). Five have diameters within the range 230-290. The ditch systems consist of one to four rings, or incomplete rings, of segments of variable length separated by cause ways of variable width. The three rings at Windmill Hill must all be regarded as integral parts of the original plan, for they ean be shown to have been contemporary (Smith, 1965, p. -

English Heritage Extensive Urban Survey an Archaeological

English Heritage Extensive Urban Survey An archaeological assessment of Clare Gathercole N. Farrow Corporate Director Environment and Property Department Somerset County Council County Hall TAUNTON Somerset TA1 4DY Somerset Extensive Urban Survey - Down End Archaeological Assessment SOMERSET EXTENSIVE URBAN SURVEY DOWN END ARCHAEOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT by Clare Gathercole CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................................... .................. 3 II. MAJOR SOURCES ................................................... ................ 3 III. A BRIEF HISTORY OF DOWN END ................................................... 3 IV. THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF DOWN END ................................................ 4 GENERAL COMMENTS ................................................... 4 1. PREHISTORIC ................................................... ............. 4 2. ROMAN ................................................... ................... 4 3. SAXON ................................................... .................... 5 4. MEDIEVAL ................................................... ................ 5 5. POST-MEDIEVAL ................................................... .......... 7 6. INDUSTRIAL (LATE 18TH/ 19TH CENTURY) ...................................... 8 7. 20TH CENTURY ................................................... ........... 10 V. THE POTENTIAL OF DOWN END ................................................... 11 1. Research interests ................................................... ........... 11 2. Areas of -

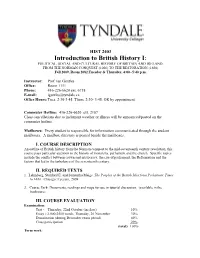

Introduction to British History I

HIST 2403 Introduction to British History I: POLITICAL, SOCIAL AND CULTURAL HISTORY OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND, FROM THE NORMAN CONQUEST (1066) TO THE RESTORATION (1660) Fall 2009, Room 2082,Tuesday & Thursday, 4:00--5:40 p.m. Instructor: Prof. Ian Gentles Office: Room 1111 Phone: 416-226-6620 ext. 6718 E-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Tues. 2:30-3:45, Thurs. 2:30- 3:45, OR by appointment Commuter Hotline: 416-226-6620 ext. 2187 Class cancellations due to inclement weather or illness will be announced/posted on the commuter hotline. Mailboxes: Every student is responsible for information communicated through the student mailboxes. A mailbox directory is posted beside the mailboxes. I. COURSE DESCRIPTION An outline of British history from the Norman conquest to the mid-seventeenth century revolution, this course pays particular attention to the history of monarchy, parliament and the church. Specific topics include the conflict between crown and aristocracy, the rise of parliament, the Reformation and the factors that led to the turbulence of the seventeenth century. II. REQUIRED TEXTS 1. Lehmberg, Stanford E. and Samantha Meigs. The Peoples of the British Isles from Prehistoric Times to 1688 . Chicago: Lyceum, 2009 2. Course Pack: Documents, readings and maps for use in tutorial discussion. (available in the bookstore) III. COURSE EVALUATION Examination : Test - Thursday, 22nd October (in class) 10% Essay - 2,000-2500 words, Thursday, 26 November 30% Examination (during December exam period) 40% Class participation 20% (total) 100% Term work : a. You are expected to attend the tutorials, preparing for them through the lectures and through assigned reading. -

Two Middle Neolithic Radiocarbon Dates from the East Midlands

THE NEWSLASTetteR OF THE PREHISTORIC SOCIetY P Registered Office: University College London, Institute of Archaeology, 31–34 Gordon Square, London WC1H 0PY http://www.prehistoricsociety.org/ Two Middle Neolithic radiocarbon dates from the East Midlands Earlier this year, radiocarbon dates were commissioned for awaiting confirmation of post-excavation funding. The two Middle Neolithic artefacts from the east Midlands. The bowl was originally identified as a Food Vessel. It has a fine first was obtained from a macehead of red deer antler from thin fabric, a concave neck, rounded body and foot-ring. Watnall, Northamptonshire, currently in the collections It is decorated all over with incised herring bone motif and of the National Museums Scotland who acquired it in certainly has a Food Vessel form. However the rim form is 1946/7. The macehead is No. 2 in Simpson’s corpus (PPS much more in keeping with Impressed Ware ceramics and 1996). It is of standard ‘crown’ type, it is undecorated, and the foot-ring has been added to an otherwise rounded base. unfortunately the circumstances of the find are unknown. Both the foot-ring and the decorated lower part of the vessel A radiocarbon date was obtained from the antler itself and are features more common in Food Vessels than in Impressed produced a result of 4395±30 BP (SUERC-40112). This date Wares. Could this be a missing link? Does this vessel bridge unfortunately coincides with a plateau in the calibration curve the Impressed Ware-Food Vessel gap? A later Neolithic or but nevertheless calibrates to 3097–2916 cal BC (95.4% Chalcolithic date was expected but instead the date is very probability) and is in keeping with the few available dates firmly in the Middle Neolithic – 4790±35 BP (SUERC- already obtained for these artefacts (see Loveday et al. -

A History of English Literature MICHAEL ALEXANDER

A History of English Literature MICHAEL ALEXANDER [p. iv] © Michael Alexander 2000 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W 1 P 0LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2000 by MACMILLAN PRESS LTD Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and London Companies and representatives throughout the world ISBN 0-333-91397-3 hardcover ISBN 0-333-67226-7 paperback A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 O1 00 Typeset by Footnote Graphics, Warminster, Wilts Printed in Great Britain by Antony Rowe Ltd, Chippenham, Wilts [p. v] Contents Acknowledgements The harvest of literacy Preface Further reading Abbreviations 2 Middle English Literature: 1066-1500 Introduction The new writing Literary history Handwriting