Writing Another Continent's History: the British and Pre-Colonial Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colony and Empire, Colonialism and Imperialism: a Meaningful Distinction?

Comparative Studies in Society and History 2021;63(2):280–309. 0010-4175/21 © The Author(s), 2021. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Society for the Comparative Study of Society and History doi:10.1017/S0010417521000050 Colony and Empire, Colonialism and Imperialism: A Meaningful Distinction? KRISHAN KUMAR University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA It is a mistaken notion that planting of colonies and extending of Empire are necessarily one and the same thing. ———Major John Cartwright, Ten Letters to the Public Advertiser, 20 March–14 April 1774 (in Koebner 1961: 200). There are two ways to conquer a country; the first is to subordinate the inhabitants and govern them directly or indirectly.… The second is to replace the former inhabitants with the conquering race. ———Alexis de Tocqueville (2001[1841]: 61). One can instinctively think of neo-colonialism but there is no such thing as neo-settler colonialism. ———Lorenzo Veracini (2010: 100). WHAT’ S IN A NAME? It is rare in popular usage to distinguish between imperialism and colonialism. They are treated for most intents and purposes as synonyms. The same is true of many scholarly accounts, which move freely between imperialism and colonialism without apparently feeling any discomfort or need to explain themselves. So, for instance, Dane Kennedy defines colonialism as “the imposition by foreign power of direct rule over another people” (2016: 1), which for most people would do very well as a definition of empire, or imperialism. Moreover, he comments that “decolonization did not necessarily Acknowledgments: This paper is a much-revised version of a presentation given many years ago at a seminar on empires organized by Patricia Crone, at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton. -

Age of Exploration Flyer

POSTER INSIDE POSTER Age of Exploration A DIGITAL RESOURCE Introduction Explore five centuries of journeys across the globe, scientific discoveries, the expansion of European colonialism, new trade routes, and conflict over territories. Overview This impressive multi-archive collection focuses on “This remarkable collection European, maritime exploration from the earliest voyages of Vasco da Gama and Christopher provides the documentary Columbus, through the age of discovery, the search base to interpret some of the for the ‘New World’, the establishment of European settlements on every continent, to the eventual major movements of the age discovery of the Northwest and Northeast Passages, of exploration. The variety and the race for the Poles. of the sources made available Bringing together material from twelve archives from opens perspectives that should around the world, this collection includes documents challenge students and bring the relating to major events in European maritime history from the voyages of James Cook to the search for period to life. It is a collection John Franklin’s doomed mission to the Northwest that promotes both historical Passage. It contains a host of additional features for analysis and imagination.” teaching, such as an interactive map which presents an in-depth visualisation of over 50 of these Emeritus Professor John Gascoigne influential voyages. University of New South Wales Highlights Material Types • Captain Cook’s secret instructions, ships’ logs and • Le Livre des merveilles by Marco Polo including the • Diaries, journals and ships’ logbooks journals from three voyages of James Cook, written illuminations of Maître d’Egerton – this illuminated Printed and manuscript books by various crew members and Cook himself which relate manuscript compendium dates from c.1410-1412 and • to early British Pacific exploration and the search for is comprised of geographical works and accounts of • Correspondence, notes and ephemera Terra Australis. -

Colonialism and Economic Development in Africa

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES COLONIALISM AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT IN AFRICA Leander Heldring James A. Robinson Working Paper 18566 http://www.nber.org/papers/w18566 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 November 2012 We are grateful to Jan Vansina for his suggestions and advice. We have also benefitted greatly from many discussions with Daron Acemoglu, Robert Bates, Philip Osafo-Kwaako, Jon Weigel and Neil Parsons on the topic of this research. Finally, we thank Johannes Fedderke, Ewout Frankema and Pim de Zwart for generously providing us with their data. The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2012 by Leander Heldring and James A. Robinson. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Colonialism and Economic Development in Africa Leander Heldring and James A. Robinson NBER Working Paper No. 18566 November 2012 JEL No. N37,N47,O55 ABSTRACT In this paper we evaluate the impact of colonialism on development in Sub-Saharan Africa. In the world context, colonialism had very heterogeneous effects, operating through many mechanisms, sometimes encouraging development sometimes retarding it. In the African case, however, this heterogeneity is muted, making an assessment of the average effect more interesting. -

Imperialism Tate Britain: Colonialism Tate Britain Has Over 500 Pieces of Art That Are Related to British Colonialism. There Ar

Imperialism Tate Britain: Colonialism Tate Britain has over 500 pieces of art that are related to British Colonialism. There are portraits, propaganda and photographs. Mutiny at the Margin: The Indian Uprising of 1857 2007 saw the 150th Anniversary of the Indian Uprising (also known as the ‘Mutiny') of 1857-58. One of the best-known episodes of both British imperial and South Asian history and a seminal event for Anglo-Indian relations, 1857 has yet to be the subject of a substantial revisionist history British Postal Museum and Archive: British Empire Exhibition Great Britain’s first commemorative stamps were issued on 23 April 1924 – this marked the first day of the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley. British Cartoon Archive: British Empire The British Cartoon Archive has a collection of 280 contemporary cartoons that are related to the British Empire. The Word on the Street: Emigration This contains a collection of 44 ballads that are related to British emigration during the 1800/1900’s. British Pathe: Empire British Pathe has a collection of contemporary newsreels that are related to the empire. Included, for example, is footage from Empire Day celebration in 1933. The British Library: Asians in Britain These webpages trace the long history of Asians in Britain, focusing on the period 1858-1950. They explore the subject through contemporary accounts, posters, pamphlets, diaries, newspapers, political reports and illustrations, all evidence of the diverse and rich contributions Asians have made to British life. The National Archives: British Empire The National Archives has an exhibition that analyses the growth of the British Empire. -

English Society 1660±1832

ENGLISH SOCIETY 1660±1832 Religion, ideology and politics during the ancien regime J. C. D. CLARK published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, UK www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011±4211, USA www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia Ruiz de AlarcoÂn 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain # Cambridge University Press 2000 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published as English Society 1688±1832,1985. Second edition, published as English Society 1660±1832 ®rst published 2000. Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Baskerville 11/12.5 pt. System 3b2[ce] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data Clark, J. C. D. English society, 1660±1832 : religion, ideology, and politics during the ancien regime/J.C.D.Clark. p. cm. Rev. edn of: English society, 1688±1832. 1985. Includes index. isbn 0 521 66180 3 (hbk) ± isbn 0 521 66627 9 (pbk) 1. Great Britain ± Politics and government ± 1660±1714. 2. Great Britain ± Politics and government ± 18th century. 3. Great Britain ± Politics and government ± 1800±1837. 4. Great Britain ± Social conditions. i.Title. ii.Clark,J.C.D.Englishsociety,1688±1832. -

Palaeoecological, Archaeological and Historical Data and the Making of Devon Landscapes

bs_bs_banner Palaeoecological, archaeological and historical data and the making of Devon landscapes. I. The Blackdown Hills ANTONY G. BROWN, CHARLOTTE HAWKINS, LUCY RYDER, SEAN HAWKEN, FRANCES GRIFFITH AND JACKIE HATTON Brown, A. G., Hawkins, C., Ryder, L., Hawken, S., Griffith, F. & Hatton, J.: Palaeoecological, archaeological and historical data and the making of Devon landscapes. I. The Blackdown Hills. Boreas. 10.1111/bor.12074. ISSN 0300-9483. This paper presents the first systematic study of the vegetation history of a range of low hills in SW England, UK, lying between more researched fenlands and uplands. After the palaeoecological sites were located bespoke archaeological, historical and documentary studies of the surrounding landscape were undertaken specifically to inform palynological interpretation at each site. The region has a distinctive archaeology with late Mesolithic tool scatters, some evidence of early Neolithic agriculture, many Bronze Age funerary monuments and Romano- British iron-working. Historical studies have suggested that the present landscape pattern is largely early Medi- eval. However, the pollen evidence suggests a significantly different Holocene vegetation history in comparison with other areas in lowland England, with evidence of incomplete forest clearance in later-Prehistory (Bronze−Iron Age). Woodland persistence on steep, but poorly drained, slopes, was probably due to the unsuit- ability of these areas for mixed farming. Instead they may have been under woodland management (e.g. coppicing) associated with the iron-working industry. Data from two of the sites also suggest that later Iron Age and Romano-British impact may have been geographically restricted. The documented Medieval land manage- ment that maintained the patchwork of small fields, woods and heathlands had its origins in later Prehistory, but there is also evidence of landscape change in the 6th–9th centuries AD. -

Colonialism, Political, Economic and Social Impacts, Africa

Impacts of Colonialism - A Research Survey 1 Patrick Ziltener University of Zurich, Switzerland zaibat@soziologie .unizh.ch Daniel Kunzler University of Fribourg, Switzerland daniel.kuenzler@un ifr.ch Abstract The impacts of colonialism in Africa and Asia have never been compared in a systematic manner for a large sample of countries. This research survey presents the results of a new and thorough assessment of the highly diverse phenomenon - including length of domination , violence, partition, proselytization, instrumentalization of ethno-linguistic and religious cleavages, trade, direct investment, settlements, plantations, and migration - organized through a dimensional analysis (political, social, and economic impacts). It is shown that while in some areas, colonial domination has triggered profound changes in economy and social structure, others have remained almost untouched. Keywords: Colonialism, political, economic and social impact s, Africa, Asia There is a stron g tradition of empirical-quantitativ e research from a world systems perspective (see, among other s, Bomschier and Chase-Dunn 1985). This research, howev er, has until recently been confined to indir ect mea suring of historicall y earlier factors, although it stresses theoreticall y the importance of long-term historical factors. According to Sanderson, world-systems analys is "tends to ignore the pre capitalist history of these societies [... ] this history often turns out to be of critical importance in conditioning the way in which any given society will be incorporat ed into the capitali st system and the effects of that incorporation" (Sanderson 2005: 188). For Kerbo (2005a: 430), scholarship has "yet to consider that East and Southeast Asian countries more generall y are somehow different from Latin American and African nations when it comes to important aspects of political economy that might interact with the affects of outside multin ational corporate investment. -

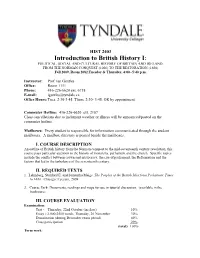

Introduction to British History I

HIST 2403 Introduction to British History I: POLITICAL, SOCIAL AND CULTURAL HISTORY OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND, FROM THE NORMAN CONQUEST (1066) TO THE RESTORATION (1660) Fall 2009, Room 2082,Tuesday & Thursday, 4:00--5:40 p.m. Instructor: Prof. Ian Gentles Office: Room 1111 Phone: 416-226-6620 ext. 6718 E-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Tues. 2:30-3:45, Thurs. 2:30- 3:45, OR by appointment Commuter Hotline: 416-226-6620 ext. 2187 Class cancellations due to inclement weather or illness will be announced/posted on the commuter hotline. Mailboxes: Every student is responsible for information communicated through the student mailboxes. A mailbox directory is posted beside the mailboxes. I. COURSE DESCRIPTION An outline of British history from the Norman conquest to the mid-seventeenth century revolution, this course pays particular attention to the history of monarchy, parliament and the church. Specific topics include the conflict between crown and aristocracy, the rise of parliament, the Reformation and the factors that led to the turbulence of the seventeenth century. II. REQUIRED TEXTS 1. Lehmberg, Stanford E. and Samantha Meigs. The Peoples of the British Isles from Prehistoric Times to 1688 . Chicago: Lyceum, 2009 2. Course Pack: Documents, readings and maps for use in tutorial discussion. (available in the bookstore) III. COURSE EVALUATION Examination : Test - Thursday, 22nd October (in class) 10% Essay - 2,000-2500 words, Thursday, 26 November 30% Examination (during December exam period) 40% Class participation 20% (total) 100% Term work : a. You are expected to attend the tutorials, preparing for them through the lectures and through assigned reading. -

European Voyages of Exploration: Christopher Columbus and the Spanish Empire

European Voyages of Exploration: Christopher Columbus and the Spanish Empire The Spanish Empire During the period from the late fifteenth through the seventeenth century, the Spanish empire expanded the extent of its power, influence, and wealth throughout the world. In particular the Spanish were responsible for exploring, conquering, and colonizing significant portions of Central America, South America, and the Caribbean. The Spanish Empire, along with neighboring Portugal, launched the period known in European history as the Age of Discovery or the Age of Exploration. Compared to Portugal, Spain succeeded in establishing more permanent and complex settlements in the New World, largely through centralized colonial governments. During the Age of Discovery several other burgeoning European empires such as England and France followed the lead of the Spanish Crown and increasingly extended their power and influence throughout the New World. Starting in 1492, Queen Isabella of Castile and King Ferdinand of Aragon largely spearheaded the Age of Exploration under the newly unified kingdom of Spain. Before 1492, the Canary Islands were Spain’s only substantial territorial possession outside of Europe. By the end of the first half of the sixteenth century the Spanish Empire controlled territories in Africa, the Caribbean, and significant portions of Central and South America. During the reign of Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand, Spain’s empire grew and developed exponentially, as overseas exploration and colonization became one of the most important priorities for the Crown. The Spanish monarchy had the financial and political freedom to devote their resources to oceanic voyages because of the relative peace in Europe during this period that resulted from several marriages between other European royal households. -

Racism, Oligarchy and Contentious Politics in Bermuda Andrea Dean [email protected]

Western University Scholarship@Western MA Research Paper Sociology Department September 2017 Racism, Oligarchy and Contentious Politics in Bermuda Andrea Dean [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/sociology_masrp Part of the Politics and Social Change Commons Recommended Citation Dean, Andrea, "Racism, Oligarchy and Contentious Politics in Bermuda" (2017). MA Research Paper. 16. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/sociology_masrp/16 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology Department at Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in MA Research Paper by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Racism, Oligarchy and Contentious Politics in Bermuda by Andrea S. Dean A research paper accepted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Sociology The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada Supervisor: Dr. Anton Allahar 2017 ABSTRACT In 1959, ‘blacks’ in Bermuda boycotted the island’s movie theatres and held nightly protests over segregated seating practices. By all accounts the 1959 Theatre Boycott was one of the most significant episodes of contentious politics in contemporary Bermuda, challenging social norms that had been in existence for 350 years. While the trajectory and outcomes of ‘black’ Bermudians’ transgressive social protests could not have been predicted, this analysis uses racism, oligarchy and contentious politics as conceptual tools to illuminate the social mechanisms and processes that eventually led to the end of formal racial segregation in Bermuda after less than three weeks of limited and non-violent collective action. -

A History of English Literature MICHAEL ALEXANDER

A History of English Literature MICHAEL ALEXANDER [p. iv] © Michael Alexander 2000 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W 1 P 0LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2000 by MACMILLAN PRESS LTD Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and London Companies and representatives throughout the world ISBN 0-333-91397-3 hardcover ISBN 0-333-67226-7 paperback A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 O1 00 Typeset by Footnote Graphics, Warminster, Wilts Printed in Great Britain by Antony Rowe Ltd, Chippenham, Wilts [p. v] Contents Acknowledgements The harvest of literacy Preface Further reading Abbreviations 2 Middle English Literature: 1066-1500 Introduction The new writing Literary history Handwriting -

The History of England A. F. Pollard

The History of England A study in political evolution A. F. Pollard, M.A., Litt.D. CONTENTS Chapter. I. The Foundations of England, 55 B.C.–A.D. 1066 II. The Submergence of England, 1066–1272 III. Emergence of the English People, 1272–1485 IV. The Progress of Nationalism, 1485–1603 V. The Struggle for Self-government, 1603–1815 VI. The Expansion of England, 1603–1815 VII. The Industrial Revolution VIII. A Century of Empire, 1815–1911 IX. English Democracy Chronological Table Bibliography Chapter I The Foundations of England 55 B.C.–A.D. 1066 "Ah, well," an American visitor is said to have soliloquized on the site of the battle of Hastings, "it is but a little island, and it has often been conquered." We have in these few pages to trace the evolution of a great empire, which has often conquered others, out of the little island which was often conquered itself. The mere incidents of this growth, which satisfied the childlike curiosity of earlier generations, hardly appeal to a public which is learning to look upon historical narrative not as a simple story, but as an interpretation of human development, and upon historical fact as the complex resultant of character and conditions; and introspective readers will look less for a list of facts and dates marking the milestones on this national march than for suggestions to explain the formation of the army, the spirit of its leaders and its men, the progress made, and the obstacles overcome. No solution of the problems presented by history will be complete until the knowledge of man is perfect; but we cannot approach the threshold of understanding without realizing that our national achievement has been the outcome of singular powers of assimilation, of adaptation to changing circumstances, and of elasticity of system.