Se,Veri\ E.Stuary Levels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mill Cottage the Mill Cottage Cockercombe, Over Stowey, Bridgwater, TA5 1HJ Taunton 8 Miles

The Mill Cottage The Mill Cottage Cockercombe, Over Stowey, Bridgwater, TA5 1HJ Taunton 8 Miles • 4.2 Acres • Stable Yard • Mill Leat & Stream • Parkland and Distant views • 3 Reception Rooms • Kitchen & Utility • 3 Bedrooms (Master En-Suite) • Garden Office Guide price £650,000 Situation The Mill Cottage is situated in the picturesque hamlet of Cockercombe, within the Quantock Hills, England's first Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. This is a very attractive part of Somerset, renowned for its beauty, with excellent riding, walking and other country pursuits. There is an abundance of footpaths and bridleways. The village of Nether Stowey is 2 miles away and Kingston St A charming Grade II Listed cottage with yard, stabling, 4.2 Acres of Mary is 5 miles away. Taunton, the County Town of Somerset, is some 8 miles to the South. Nether Stowey is an attractive centre land and direct access to the Quantock Hills. with an extensive range of local facilities, which are further supplemented by the town of Bridgwater, some 8 miles to the East. Taunton has a wide range of facilities including a theatre, county cricket ground and racecourse. Taunton is well located for national communications, with the M5 motorway at Junction 25 and there is an excellent intercity rail service to London Paddington (an hour and forty minutes). The beautiful coastline at Kilve is within 15 minutes drive. Access to Exmoor and the scenic North Somerset coast is via the A39 or through the many country roads in the area. The Mill Cottage is in a wonderful private location in a quiet lane, with clear views over rolling countryside. -

SCC Covers (Page 1)

Somerset Local Transport Plan 2006-2011 VISION, OBJECTIVES & PRIORITIES - 1 15 Somerset Local Transport Plan 2006-2011 1 VISION, OBJECTIVES & PRIORITIES 1 VISION, OBJECTIVES & PRIORITIES Our vision for transport in Somerset builds upon the overarching community strategy 'vision' of the Somerset Strategic Partnership for 2025: Somerset Strategic Partnership Vision "A dynamic, successful, modern economy that supports, respects and develops Somerset's distinctive communities and unique environments". 1.1 TRANSPORT OBJECTIVES The National shared priorities for transport form the basis of our objectives for this LTP which are set out below. We have adopted environmental objectives to reflect Somerset’s unique landscape, heritage and biodiversity, and have also adopted economic objectives to reflect the regional priority for investment in our larger growth centres as well as the community strategy vision for economic regeneration. Improve safety for all who travel by meeting the following objectives: Reducing traffic accidents with a particular emphasis on killed and seriously injured casualties and rural main roads; and Reducing fear of crime in all aspects of the transport network. Reduce social exclusion and improve access to everyday facilities by meeting the following objectives: Improving access to work, learning, healthcare, food-shops and other services; Improving access to the countryside and recreation; and Facilitating the better co-ordination of activities of other authorities to improve accessibility of services. Reduce growth -

River Brue's Historic Bridges by David Jury

River Brue’s Historic Bridges By David Jury The River Brue’s Historic Bridges In his book "Bridges of Britain" Geoffrey Wright writes: "Most bridges are fascinating, many are beautiful, particularly those spanning rivers in naturally attractive settings. The graceful curves and rhythms of arches, the texture of stone, the cold hardness of iron, the stark simplicity of iron, form constant contrasts with the living fluidity of the water which flows beneath." I cannot add anything to that – it is exactly what I see and feel when walking the rivers of Somerset and discover such a bridge. From source to sea there are 58 bridges that span the River Brue, they range from the simple plank bridge to the enormity of the structures that carry the M5 Motorway. This article will look at the history behind some of those bridges. From the river’s source the first bridge of note is Church Bridge in South Brewham, with it’s downstream arch straddling the river between two buildings. Figure 1 - Church Bridge South Brewham The existing bridge is circa 18th century but there was a bridge recorded here in 1258. Reaching Bruton, we find Church Bridge described by John Leland in 1525 as the " Est Bridge of 3 Archys of Stone", so not dissimilar to what we have today, but in 1757 the bridge was much narrower “barely wide enough for a carriage” and was widened on the east side sometime in the early part of the 19th century. Figure 2 - Church Bridge Bruton Close by we find that wonderful medieval Bow Bridge or Packhorse Bridge constructed in the 15th century with its graceful slightly pointed chamfered arch. -

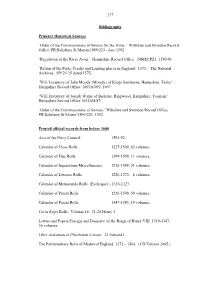

217 Bibliography Primary Historical Sources 'Order Of

217 Bibliography Primary Historical Sources ‘Order of the Commissioners of Sewers for the Avon.’ Wiltshire and Swindon Record Office, PR/Salisbury St Martin/1899/223 - date 1592. ‘Regulation of the River Avon.’ Hampshire Record Office. 24M82/PZ3. 1590-91. ‘Return of the Ports, Creeks and Landing places in England. 1575.’ The National Archives. SP12/135 dated 1575. ‘Will, Inventory of John Moody (Mowdy) of Kings Somborne, Hampshire. Tailor.’ Hampshire Record Office. 1697A/099. 1697. ‘Will, Inventory of Joseph Warne of Bisterne, Ringwood, Hampshire, Yeoman.’ Hampshire Record Office 1632AD/87. ‘Order of the Commissioners of Sewers.’ Wiltshire and Swindon Record Office, PR/Salisbury St Martin/1899/223. 1592. Printed official records from before 1600 Acts of the Privy Council. 1591-92. Calendar of Close Rolls. 1227-1509, 62 volumes. Calendar of Fine Rolls. 1399-1509, 11 volumes. Calendar of Inquisitions Miscellaneous. 1216-1509, 21 volumes. Calendar of Liberate Rolls. 1226-1272, 6 volumes. Calendar of Memoranda Rolls. (Exchequer.) 1326-1327. Calendar of Patent Rolls. 1226-1509, 59 volumes. Calendar of Patent Rolls. 1547-1583, 19 volumes. Curia Regis Rolls. Volume 16. 21-26 Henry 3. Letters and Papers Foreign and Domestic of the Reign of Henry VIII. 1519-1547, 36 volumes. Liber Assisarum et Placitorum Corone. 23 Edward I. The Parliamentary Rolls of Medieval England. 1272 – 1504. (CD Version 2005.) 218 Placitorum in Domo Capitulari Westmonasteriensi Asservatorum Abbreviatio. (Abbreviatio Placitorum.) 1811. Rotuli Hundredorum. Volume I. Statutes at Large. 42 Volumes. Statutes of the Realm. 12 Volumes. Year Books of the Reign of King Edward the Third. Rolls Series. Year XIV. Printed offical records from after 1600 Calendar of State Papers, Domestic Series, of the Reign of Charles I. -

Coridor-Yr-M4-O-Amgylch-Casnewydd

PROSIECT CORIDOR YR M4 O AMGYLCH CASNEWYDD THE M4 CORRIDOR AROUND NEWPORT PROJECT Malpas Llandifog/ Twneli Caerllion/ Caerleon Llandevaud B Brynglas/ 4 A 2 3 NCN 4 4 Newidiadau Arfaethedig i 6 9 6 Brynglas 44 7 Drefniant Mynediad/ A N tunnels C Proposed Access Changes 48 N Pontymister A 4 (! M4 C25/ J25 6 0m M4 C24/ J24 M4 C26/ J26 2 p h 4 h (! (! p 0 Llanfarthin/ Sir Fynwy/ / 0m 4 u A th 6 70 M4 Llanmartin Monmouthshire ar m Pr sb d ph Ex ese Gorsaf y Ty-Du/ do ifie isti nn ild ss h ng ol i Rogerstone A la p M4 'w A i'w ec 0m to ild Station ol R 7 Sain Silian/ be do nn be Re sba Saint-y-brid/ e to St. Julians cla rth res 4 ss u/ St Brides P M 6 Underwood ifi 9 ed 4 ng 5 Ardal Gadwraeth B M ti 4 Netherwent 4 is 5 x B Llanfihangel Rogiet/ 9 E 7 Tanbont 1 23 Llanfihangel Rogiet B4 'St Brides Road' Tanbont Conservation Area t/ Underbridge en Gwasanaethau 'Rockfield Lane' w ow Gorsaf Casnewydd/ Trosbont -G st Underbridge as p Traffordd/ I G he Newport Station C 4 'Knollbury Lane' o N Motorway T Overbridge N C nol/ C N Services M4 C23/ sen N Cyngor Dinas Casnewydd M48 Pre 4 Llanwern J23/ M48 48 Wilcrick sting M 45 Exi B42 Newport City Council Darperir troedffordd/llwybr beiciau ar hyd Newport Road/ M4 C27/ J27 M4 C23A/ J23A Llanfihangel Casnewydd/ Footpath/ Cycleway Provided Along Newport Road (! Gorsaf Pheilffordd Cyffordd Twnnel Hafren/ A (! 468 Ty-Du/ Parcio a Theithio Arfaethedig Trosbont Rogiet/ Severn Tunnel Junction Railway Station Newport B4245 Grorsaf Llanwern/ Trefesgob/ 'Newport Road' Rogiet Rogerstone 4 Proposed Llanwern Overbridge -

Langport and Frog Lane

English Heritage Extensive Urban Survey An archaeological assessment of Langport and Frog Lane Miranda Richardson Jane Murray Corporate Director Culture and Heritage Directorate Somerset County Council County Hall TAUNTON Somerset TA1 4DY 2003 SOMERSET EXTENSIVE URBAN SURVEY LANGPORT AND FROG LANE ARCHAEOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT by Miranda Richardson CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................... .................................. 3 II. MAJOR SOURCES ............................... ................................... 3 1. Primary documents ............................ ................................ 3 2. Local histories .............................. .................................. 3 3. Maps ......................................... ............................... 3 III. A BRIEF HISTORY OF LANGPORT . .................................. 3 IV. THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF LANGPORT . .............................. 4 1. PREHISTORIC and ROMAN ........................ ............................ 4 2. SAXON ........................................ .............................. 7 3. MEDIEVAL ..................................... ............................. 9 4. POST-MEDIEVAL ................................ ........................... 14 5. INDUSTRIAL (LATE 18TH AND 19TH CENTURY) . .......................... 15 6. 20TH CENTURY ................................. ............................ 18 V. THE POTENTIAL OF LANGPORT . ............................... 19 1. Research interests........................... ................................. -

Appendix 6: Energy Sector Detailed Report What This Area of Work

Appendix 6: Energy Sector Detailed Report What This Area of Work Covers The focus of this area of work is: • Energy conservation and energy efficiency; • Increasing levels of low carbon and renewable energy generation and storage; • Facilitating the transition to a smart, flexible energy system. A zero-carbon world is predominantly electric. Power generation from clean renewable and low carbon sources will need to accelerate to support the increase in electrical demand resulting from the electrification and decarbonisation of heat and transport. Due to the increased role of electricity, the existing capacity issues on the distribution network will need to be addressed. A whole systems approach to energy is required, integrating energy conservation, efficiency, heat, power and transport supported by a smart, resilient and flexible grid network with greater participation from consumers. The transition to a zero-carbon economy can address the energy trilemma (security of supply, affordability and environmental sustainability), making the UK’s energy system: • Integrated: The energy system needs to be smart, resilient and secure, • Affordable: The energy system will be affordable, to alleviate fuel poverty and allow businesses to be competitive, • Zero carbon: The energy system needs to decarbonise by 2050 to meet legally binding targets. Local authorities are in a key position to enable the transition and to demonstrate leadership and we have the following recommended outcomes for Somerset: Page 1 of 30 • DEVELOP AND DELIVER AN ENERGY PLAN FOR SOMERSET- ROADMAP TO DECARBONISING THE ENERGY SYSTEM IN SOMERSET. WHOLE SYSTEMS APPROACH (BUILDINGS, HEAT, TRANSPORT AND POWER GENERATION). • LOCAL AUTHORITY ENERGY PERFORMANCE IS SMARTER, MORE EFFICIENT AND ELIMINATES THE USE OF FOSSIL FUELS FOR HEATING AND TRANSPORT BY 2030 (ESTATE AND OPERATIONS) • 100% OF LOCAL AUTHORITY ENERGY DEMAND IS MET THROUGH LOCALLY GENERATED AND LOCALLY OWNED LOW CARBON AND RENEWABLE ENERGY BY 2030 (ESTATE AND OPERATIONS). -

Llanwern Solar Farm, Newport NP18 2AY Zone of Theoretical Visibility

Christchurch 23 Gwent Farmers te si e Community th M4 m M4 o Solar Scheme fr Ringland m k 5 te si 17 Llanwern Solar Farm, e Alway th m Newport NP18 2AY o 16 fr 13 Llanwern 14 m Hill k Zone of 4 LA. 07-2 te si e Theoretical Visibility th m 15 Screening Features Analysis ro Magor/ f NEWPORT/ Magwyr m k 3 CASNEWYDD te si e Steel Works th Key m o r f Site boundary m k e 2 sit 1km Buffers from site boundary he t A4810 m o Lafarge Unitary Authority boundary fr Tarmac m k Assessment viewpoint photograph locations 1 Refer to A091650 LA15 for photographs 2 20 Bowleaze Reen Viewpoint photograph locations Refer to A091650 LA16 for photographs 3 El Sub Sta North Row 21 1 NCR 4 22 Photomontage locations NCR 4 Pye Chapel Reen Refer to A091650 LA17 for photographs Corner Broadstreet Common Public Access : 4 Wainbridge 5 Whitson Court 10 Elyer Pill Reen Public Footpaths Little NCR 4 Newra The Half Acre Public Bridleways 7 6 Wainbridge Reen Common Whitson Road Redwick 9 Wales Coast Path Pipe Lines 8 River Usk / Afon Wysg Nash 'NCR 4' National Cycle Route Power Chapel Road Station Heritage Designations : Whitson Hare's Reen 18 'Gwent Levels' 11 Landscape of Outstanding Historic Interest Great Porton Wales Coast Path Historic Parks and Gardens Newport Wetlands Goldcliff19 National Nature Reserve 12 Scheduled Monuments Listed Buildings Wales Coast Path Zone of Theoretical Visibility : Screening Features Analysis Majority of the solar farm visible Moderate part of the solar farm visible Small part of the solar farm visible Woodland included in analysis 0 200 400 800 1,200 1,600 2,000 m ZTV Note: The computer generated Zone of Theoretical Visibility (ZTV) is based on a digital surface model generated from the 5m grid interval Ordnance Survey OS Terrain 5® dataset. -

Palaeoecological, Archaeological and Historical Data and the Making of Devon Landscapes

bs_bs_banner Palaeoecological, archaeological and historical data and the making of Devon landscapes. I. The Blackdown Hills ANTONY G. BROWN, CHARLOTTE HAWKINS, LUCY RYDER, SEAN HAWKEN, FRANCES GRIFFITH AND JACKIE HATTON Brown, A. G., Hawkins, C., Ryder, L., Hawken, S., Griffith, F. & Hatton, J.: Palaeoecological, archaeological and historical data and the making of Devon landscapes. I. The Blackdown Hills. Boreas. 10.1111/bor.12074. ISSN 0300-9483. This paper presents the first systematic study of the vegetation history of a range of low hills in SW England, UK, lying between more researched fenlands and uplands. After the palaeoecological sites were located bespoke archaeological, historical and documentary studies of the surrounding landscape were undertaken specifically to inform palynological interpretation at each site. The region has a distinctive archaeology with late Mesolithic tool scatters, some evidence of early Neolithic agriculture, many Bronze Age funerary monuments and Romano- British iron-working. Historical studies have suggested that the present landscape pattern is largely early Medi- eval. However, the pollen evidence suggests a significantly different Holocene vegetation history in comparison with other areas in lowland England, with evidence of incomplete forest clearance in later-Prehistory (Bronze−Iron Age). Woodland persistence on steep, but poorly drained, slopes, was probably due to the unsuit- ability of these areas for mixed farming. Instead they may have been under woodland management (e.g. coppicing) associated with the iron-working industry. Data from two of the sites also suggest that later Iron Age and Romano-British impact may have been geographically restricted. The documented Medieval land manage- ment that maintained the patchwork of small fields, woods and heathlands had its origins in later Prehistory, but there is also evidence of landscape change in the 6th–9th centuries AD. -

Welsh Government M4 Corridor Around Newport Environmental Statement Volume 1 Chapter 7: Air Quality M4CAN-DJV-EAQ-ZG GEN--REP-EN-0001.Docx

Welsh Government M4 Corridor around Newport Environmental Statement Volume 1 Chapter 7: Air Quality M4CAN-DJV-EAQ-ZG_GEN--REP-EN-0001.docx At Issue | March 2016 CVJV/AAR 3rd Floor Longross Court, 47 Newport Road, Cardiff CF24 0AD Welsh Government M4 Corridor around Newport Environmental Statement Volume 1 Contents Page 7 Air Quality 7-1 7.1 Introduction 7-1 7.2 Legislation and Policy Context 7-1 7.3 Assessment Methodology 7-7 7.4 Baseline Environment 7-28 7.5 Mitigation Measures Forming Part of the Scheme Design 7-35 7.6 Assessment of Potential Land Take Effects 7-35 7.7 Assessment of Potential Construction Effects 7-35 7.8 Assessment of Potential Operational Effects 7-42 7.9 Additional Mitigation and Monitoring 7-49 7.10 Assessment of Land Take Effects 7-53 7.11 Assessment of Construction Effects 7-53 7.12 Assessment of Operational Effects 7-53 7.13 Assessment of Cumulative Effects 7-53 7.14 Inter-relationships 7-54 7.15 Summary of Effects 7-54 Welsh Government M4 Corridor around Newport Environmental Statement Volume 1 7 Air Quality 7.1 Introduction 7.1.1 This chapter examines the potential effect of the Scheme on local and regional air quality during both the construction and operational phases. 7.1.2 The Scheme would transfer approximately 30-45% of traffic from the existing M4, between Junctions 23A and 29, onto the new section of motorway to the south of Newport. Traffic related pollution in the urban areas adjacent to the existing M4 is therefore predicted to improve as a result of the Scheme. -

United States Bankruptcy Court Eastern District of New York

Case 8-19-71020-reg Doc 178 Filed 03/22/19 Entered 03/22/19 20:59:04 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ----------------------------------------------------------------- x In re: : Chapter 11 : Décor Holdings, Inc., et al.,1 : Case No. 19-71020 (REG) : Case No. 19-71022 (REG) Debtors. : Case No. 19-71023 (REG) : Case No. 19-71024 (REG) : Case No. 19-71025 (REG) : : Jointly Administered ---------------------------------------------------------------- x AFFIDAVIT OF SERVICE State of California ) ) ss County of Los Angeles ) I, Darleen Sahagun, being duly sworn, depose and says: 1. I am employed by Omni Management Group located at 5955 DeSoto Avenue, Suite 100, Woodland Hills, CA 91367. I am over the age of eighteen years and am not a party to the above-captioned action. 2. On March 15, 2019, I caused to be served the: a. Notice of Deadline Requiring Filing of Proofs of Claim on or Before April 17, 2019 (General Bar Date) and August 11, 2019 (Governmental Bar Date), b. Official Form 410 - Proof of Claim, c. Official Form 410 - Instructions for Proof of Claim, d. Notice of Deadline Requiring Filing of Certain Administrative Claims on or Before April 17, 2019, e. Administrative Expense Proof of Claim, f. Instructions for Filing Proof of Administrative Claim Form, g. Notice of Hearing on the Motion of the Debtors for an Order (I) Approving the Disclosure Statement, (II) Establishing Plan Solicitation and Voting Procedures, (III) Scheduling a Confirmation Hearing, and (IV) Establishing Notice and Objection Procedures for Confirmation of the Debtors’ Chapter 11 Plan of Liquidation. (2a through 2g collectively referred to as the “General/Administrative Proof of Claim Packages”) By causing true and correct copies to be served via first-class mail, postage pre-paid to the names and addresses of the parties listed as follows: ----------------------------------------------------- 1 The Debtors in these chapter 11 cases, along with the last four digits of each Debtor’s federal tax identification number, are: Décor Holdings, Inc. -

English Heritage Extensive Urban Survey an Archaeological

English Heritage Extensive Urban Survey An archaeological assessment of Clare Gathercole N. Farrow Corporate Director Environment and Property Department Somerset County Council County Hall TAUNTON Somerset TA1 4DY Somerset Extensive Urban Survey - Down End Archaeological Assessment SOMERSET EXTENSIVE URBAN SURVEY DOWN END ARCHAEOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT by Clare Gathercole CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................................... .................. 3 II. MAJOR SOURCES ................................................... ................ 3 III. A BRIEF HISTORY OF DOWN END ................................................... 3 IV. THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF DOWN END ................................................ 4 GENERAL COMMENTS ................................................... 4 1. PREHISTORIC ................................................... ............. 4 2. ROMAN ................................................... ................... 4 3. SAXON ................................................... .................... 5 4. MEDIEVAL ................................................... ................ 5 5. POST-MEDIEVAL ................................................... .......... 7 6. INDUSTRIAL (LATE 18TH/ 19TH CENTURY) ...................................... 8 7. 20TH CENTURY ................................................... ........... 10 V. THE POTENTIAL OF DOWN END ................................................... 11 1. Research interests ................................................... ........... 11 2. Areas of