The Pattern of Social Transformation in England Perkin, Harold

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Society 1660±1832

ENGLISH SOCIETY 1660±1832 Religion, ideology and politics during the ancien regime J. C. D. CLARK published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, UK www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011±4211, USA www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia Ruiz de AlarcoÂn 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain # Cambridge University Press 2000 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published as English Society 1688±1832,1985. Second edition, published as English Society 1660±1832 ®rst published 2000. Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Baskerville 11/12.5 pt. System 3b2[ce] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data Clark, J. C. D. English society, 1660±1832 : religion, ideology, and politics during the ancien regime/J.C.D.Clark. p. cm. Rev. edn of: English society, 1688±1832. 1985. Includes index. isbn 0 521 66180 3 (hbk) ± isbn 0 521 66627 9 (pbk) 1. Great Britain ± Politics and government ± 1660±1714. 2. Great Britain ± Politics and government ± 18th century. 3. Great Britain ± Politics and government ± 1800±1837. 4. Great Britain ± Social conditions. i.Title. ii.Clark,J.C.D.Englishsociety,1688±1832. -

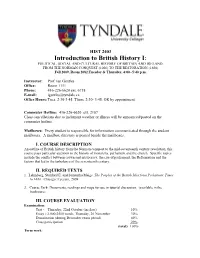

Introduction to British History I

HIST 2403 Introduction to British History I: POLITICAL, SOCIAL AND CULTURAL HISTORY OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND, FROM THE NORMAN CONQUEST (1066) TO THE RESTORATION (1660) Fall 2009, Room 2082,Tuesday & Thursday, 4:00--5:40 p.m. Instructor: Prof. Ian Gentles Office: Room 1111 Phone: 416-226-6620 ext. 6718 E-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Tues. 2:30-3:45, Thurs. 2:30- 3:45, OR by appointment Commuter Hotline: 416-226-6620 ext. 2187 Class cancellations due to inclement weather or illness will be announced/posted on the commuter hotline. Mailboxes: Every student is responsible for information communicated through the student mailboxes. A mailbox directory is posted beside the mailboxes. I. COURSE DESCRIPTION An outline of British history from the Norman conquest to the mid-seventeenth century revolution, this course pays particular attention to the history of monarchy, parliament and the church. Specific topics include the conflict between crown and aristocracy, the rise of parliament, the Reformation and the factors that led to the turbulence of the seventeenth century. II. REQUIRED TEXTS 1. Lehmberg, Stanford E. and Samantha Meigs. The Peoples of the British Isles from Prehistoric Times to 1688 . Chicago: Lyceum, 2009 2. Course Pack: Documents, readings and maps for use in tutorial discussion. (available in the bookstore) III. COURSE EVALUATION Examination : Test - Thursday, 22nd October (in class) 10% Essay - 2,000-2500 words, Thursday, 26 November 30% Examination (during December exam period) 40% Class participation 20% (total) 100% Term work : a. You are expected to attend the tutorials, preparing for them through the lectures and through assigned reading. -

A History of English Literature MICHAEL ALEXANDER

A History of English Literature MICHAEL ALEXANDER [p. iv] © Michael Alexander 2000 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W 1 P 0LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2000 by MACMILLAN PRESS LTD Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and London Companies and representatives throughout the world ISBN 0-333-91397-3 hardcover ISBN 0-333-67226-7 paperback A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 O1 00 Typeset by Footnote Graphics, Warminster, Wilts Printed in Great Britain by Antony Rowe Ltd, Chippenham, Wilts [p. v] Contents Acknowledgements The harvest of literacy Preface Further reading Abbreviations 2 Middle English Literature: 1066-1500 Introduction The new writing Literary history Handwriting -

England and the Process of Commercialization ?

Introduction ENGLAND AND THE PROCESS OF COMMERCIALIZATION ? As the core country of the British Isles, England is regarded as a pioneer of mod- ern industrial capitalism and as a model of an open society with a viable public sphere. Th erefore, an examination of English history can be expected to yield fundamental insights into the preconditions for Western ways of living and doing business. It furthermore seems legitimate to reformulate a central question of historical social science, originally posed by Max Weber: ‘to what combination of circumstances should the fact be attributed that precisely on English soil cultural phenomena appeared which (as we like to think) lie in a line of development hav- ing universal signifi cance and value?’1 With reference to this question, English – and more broadly British – history has already been the subject of numerous comprehensive research initiatives. In the 1960s and 1970s, for example, it served U.S.-based modernization theorists as a preferred model and benchmark of Western development and inspired a large number of empirically rich comparative studies that juxtaposed it with the history of other European countries, the United States and Latin America.2 Th e current debate about the ‘Great Divergence’ between Europe and Asia has rekindled this discussion. To determine when and for what reasons Asia diverged from the path of Western development, the protagonists viewed England and subregions of China as proxies for Europe and Asia, respectively. In this discus- sion, the stagnation of the Qing dynasty with its highly developed commercial economy is explained in terms of the absence of the structural preconditions that are presumed to have been present and eff ectively utilized in medieval and Early Modern England.3 Notes from this chapter begin on page 15. -

Changing Englishness: in Search of National Identity*

ISSN 1392-0561. INFORMACIJOS MOKSLAI. 2008 45 Changing Englishness: In search of national identity* Elke Schuch Cologne University of Applied Sciences Institute of Translation and Multilingual Communication Mainzer Str. 5, D-50678 Köln, Germany Ph. +49-221/8275-3302 E-mail: [email protected] The subsumation of Englishness into Britishness to the extent that they were often indistinguishable has contributed to the fact that at present an English identity is struggling to emerge as a distinct category. While devolved Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland have been able to construct a strong sense of local identity for themselves in opposition to the dominant English, England, without an e�uivalent Other, has never had to explain herself in the way Scotland or Wales have had to. But now, faced with the af- ter-effects of globalisation, devolution and an increasingly cosmopolitan and multicultural society as a conse�uence of de-colonisation and migration, the English find it difficult to invent a postimperial identity for themselves. This paper argues that there are chances and possibilities to be derived from the alleged crisis of Englishness: Britain as a nation-state has always accommodated large numbers of non-English at all levels of society. If England manages to re-invent itself along the lines of a civic, non- ethnic Britishness with which it has been identified for so long, the crisis might turn into the beginning of a more inclusive and cosmopolitan society which acknowledges not just the diversification of the people, particularly the legacy of the Empire, but also realises that the diversity of cultures has to be accommo- dated within a common culture. -

The Forest and Social Change in Early Modern English Literature, 1590–1700

The Forest and Social Change in Early Modern English Literature, 1590–1700 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Elizabeth Marie Weixel IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Dr. John Watkins, Adviser April 2009 © Elizabeth Marie Weixel, 2009 i Acknowledgements In such a wood of words … …there be more ways to the wood than one. —John Milton, A Brief History of Moscovia (1674) —English proverb Many people have made this project possible and fruitful. My greatest thanks go to my adviser, John Watkins, whose expansive expertise, professional generosity, and evident faith that I would figure things out have made my graduate studies rewarding. I count myself fortunate to have studied under his tutelage. I also wish to thank the members of my committee: Rebecca Krug for straightforward and honest critique that made my thinking and writing stronger, Shirley Nelson Garner for her keen attention to detail, and Lianna Farber for her kind encouragement through a long process. I would also like to thank the University of Minnesota English Department for travel and research grants that directly contributed to this project and the Graduate School for the generous support of a 2007-08 Doctoral Dissertation Fellowship. Fellow graduate students and members of the Medieval and Early Modern Research Group provided valuable support, advice, and collegiality. I would especially like to thank Elizabeth Ketner for her generous help and friendship, Ariane Balizet for sharing what she learned as she blazed the way through the dissertation and job search, Marcela Kostihová for encouraging my early modern interests, and Lindsay Craig for his humor and interest in my work. -

Contemporary England Instructor: Justin J

Course Title: Contemporary England Instructor: Justin J. Lorentzen Instructor Contact Details Email: [email protected] Contact phone number: TBC Office hours/office location: By Appointment Course Description: Britain is at a crossroads politically, socially and culturally. This course attempts to come to terms with the legacy of Britain’s imperial past and simultaneously analysing contemporary Britain in the light of the challenges that the country faces from a variety of political, economic and cultural sources. Key features for analysis will include: Britain’s traditional political institutions and the process of reform; the importance of social class, race and ethnicity; ‘popular culture’ v ‘high culture’. In addition, understanding the Urban experience will play a central role in the course. Course Objectives: • To provide students with a broad understanding of contemporary British social processes; • To offer students a framework with which to analyse and reflect on their experience of ‘cultural difference’. • To enable students to actively engage in the social ecology of everyday life Course Learning Outcomes: Ultimately, the course should provide students with a series of critical perspectives that will enable them to analyse, criticise, empathise and celebrate contemporary Britain. Required Text(s): Reading will be provided throughout the course, however you may find the following text Useful: Lynch, Phillip and Fairclough, Paul UK Government and Politics, Phillip Allan Updates 2011 Heffernan Richard (et al) Developments in British Politics, Macmillan 2011 Gamble, Andrew (Editor} Wright, Tony (Editor} Britishness: Perspectives on the British Question ngman 1997 (Political Quarterly Monograph Series) Wiley- Blackwell 2009 1 All rights reserved. This material may not be reproduced, displayed, modified, or distributed without the express prior written permission of FIE: Foundation for International Education. -

Otherness and Identity in the Victorian Novel

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Faculty Publications Department of English 2002 Otherness and Identity in the Victorian Novel Michael Galchinsky Georgia State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_facpub Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Galchinsky, M. (2002). Otherness and identity in the Victorian novel. In W. Baker & K. Womack (Eds.), Victorian Literary Cultures: A Critical Companion, (pp. 403-420). Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Michael Galchinsky Department of English Georgia State University Atlanta, GA 30303 [email protected] Otherness and Identity in the Victorian Novel Much recent journalism to the contrary, migrations, diasporas, and even globalization are not phenomena originating in the post-colonial, post-industrial, post-Cold War period of our own day (Crossette). Population transfer, at least, was already a prominent feature of the post- Enlightenment, post-French Revolution era of national consolidation and imperial expansion that followed the British victories of 1815. The increased mobility of populations and their concentration in cities were distinctive signs of nineteenth century Britain, driven by the Industrial Revolution’s vast production of wealth, by the slave trade and colonial expansion, and by new technologies like the train, the canal, and the steamship. Such mobility inevitably compelled the Victorians to experience greater regional, religious, racial and national diversity. -

1 HI 2101: Anglo-Saxons and Vikings: the Making of England, C.400-1000 AD. Possible Reconstruction of the Sutton Hoo Helmet

HI 2101: Anglo-Saxons and Vikings: the making of England, c.400-1000 AD. Possible reconstruction of the Sutton Hoo helmet. Welcome to this course in Senior Freshmen (2nd) year. There will be two lectures throughout the Semester, and one tutorial per week for seven weeks from Week 3. There will be no lectures or tutorials in ‘Reading Week’ 25th February-1st March 2013. Lectures are WED 11-12 Room 5082. FRI 2-3 pm Room 4047. Course Aims: This course aims to give you an outline understanding of the major developments in politics and society in Britain between the end of Roman Rule and the start of the new millennium. Outcomes: • Allow you to understand the broad chronology of the period. • Allow you to analyse the relevant literature. • Allow you also to realise the importance of key contemporary texts in translation. • Allow you to chart the main developments in early medieval society in Britain. Lectures: 1 1. General introduction to the course (TBB) 2. The governmental structure of Roman Britain (TBB) 3. The end of Roman Britain (TBB) 4. Background to the Anglo-Saxon invasions of Britain (TBB) 5. Anglo-Saxon Settlements (TBB) 6. The conversion of Anglo-Saxon England: The Augustinian Mission (TBB) 7. The conversion of England: Paulinus and Northumbria (TBB) 8. Anglo-Saxon society and the Law Codes (TBB) 9. Introduction to Anglo-Saxon art and archaeology (TBB) 10. The politics of the early Anglo-Saxon kingdoms (TBB) 11. The politics of the middle Anglo-Saxon kingdoms (TBB) 12. The “Golden Age” of Northumbria (TBB) 13. -

An Inclusive Cultural History of Early Eighteenth-Century British Literature

An Inclusive Cultural History of Early Eighteenth-Century British Literature. By: James E. Evans Evans, James E. “An Inclusive Cultural History of Early Eighteenth-Century British Literature.” Teaching the Eighteenth Century (American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies) 8 (2001): 1-13. Made available courtesy of the American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies: http://asecs.press.jhu.edu/evans.html ***Reprinted with permission. No further reproduction is authorized without written permission from the American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies. This version of the document is not the version of record. Figures and/or pictures may be missing from this format of the document. *** Abstract: During the late twentieth century the recovery of texts by women authors was an important scholarly project in English studies, which also led to paperback editions and, more recently, hypertexts for instructional use. At my university, which is probably typical, this availability contributed to two types of courses—those focused on early women authors, found in Women's Studies programs as well as English departments, and those still centered on male authors, with added novels, plays, or poems by women. Introducing their anthology Popular Fiction by Women 1660-1730, which could facilitate either type of course, Paula R. Backscheider and John J. Richetti ask this question about the selections: "Do they constitute, taken together and separately, a counter-tradition or a rival and competing set of narrative choices to the male novel of the mid-century?" While recognizing that the answer is complicated, they set me thinking about an undergraduate course that would ask their question more generally about various kinds of literature early in the eighteenth century through systematic juxtaposition of texts by previously canonical male authors with works by "recovered" female authors. -

Tudor Society

Gale Primary Sources Start at the source. Tudor Society Matthew J. Clark University of Cambridge Various source media, State Papers Online EMPOWER™ RESEARCH English society in the sixteenth and early seventeenth feed themselves and their families, with a surplus left centuries experienced intense social change.[1] The over to take to market. As many farmers employed national population was increasing rapidly: from labourers, the falling value of wages was to their around three million in 1541, it had risen to over five advantage, serving to increase profits.[6] The prosperity million at the time of Elizabeth's death in 1603, and of the sixteenth century yeomanry is evident in what would continue rising to reach a high of almost six and has been dubbed the great rebuilding of rural England, a half million in the 1650s.[2] Although people at the time as newly rich farmers enlarged, improved and had no way of measuring demographic change, they beautified their houses.[7] certainly noticed and commented on its effects. Above all, they felt it in their pockets. The most telling effect of Rural and Urban Society the rise in population was inflation as supply, Although some three-quarters of England's population particularly of basic foodstuffs, failed to keep up with lived and worked in rural communities, urban society demand. It has been calculated that the price of staple ought not to be overlooked. Towns were important as foods rose sixfold between 1500 and the early 1600s, religious and political centres, and also as sites for with almost half of that growth occurring in the years markets where agricultural produce was bought and after 1570.[3] sold. -

Orphans and Class Anxiety in Nineteenth-Century English Novels

SSStttooonnnyyy BBBrrrooooookkk UUUnnniiivvveeerrrsssiiitttyyy The official electronic file of this thesis or dissertation is maintained by the University Libraries on behalf of The Graduate School at Stony Brook University. ©©© AAAllllll RRRiiiggghhhtttsss RRReeessseeerrrvvveeeddd bbbyyy AAAuuuttthhhooorrr... Orphans and Class Anxiety in Nineteenth-century English Novels A Dissertation Presented by Junghan Choi to The Graduate School in Partial Ful¯llment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Stony Brook University August 2008 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Junghan Choi We, the dissertation committee for the above candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this dissertation. Helen M. Cooper { Dissertation Advisor Associate Professor, English Susan Scheckel { Chairperson of Defense Associate Professor, English Peter J. Manning Professor, English Lou Charnon-Deutsch Professor Hispanic Languages and Literature This dissertation is accepted by the Graduate School. Lawrence Martin Dean of the Graduate School ii Abstract of the Dissertation Orphans and Class Anxiety in Nineteenth-century English Novels by Junghan Choi Doctor of Philosophy in English Stony Brook University 2008 This dissertation discusses the most popular outsiders in nineteenth- century English novels|orphans. Both real and ¯ctional orphans are often known to formulate the threatening force that disturbs conventional domesticity and obscures social boundaries, for with- out heritage or parentage an individual in the nineteenth century is home-less, name-less, and class-less. Suggesting Mary Shel- ley's creature in Frankenstein as the ¯rst orphan prototype in nineteenth-century novels, this dissertation shows the inevitable tension between orphans and society. However, this study also argues that literary orphan characters encourage purposeful sepa- iii ration from domestic history and pursue self-reformation rejecting social and cultural interference.