Changing Englishness: in Search of National Identity*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

West Midlands' Circular Economy Routemap

West Midlands’ Circular Economy Routemap Kickstarting the region’s journey to a green circular revolution DRAFT FOR REVIEW Baseline 1 Analysis DRAFT FOR REVIEW West Midlands’ Circular Economy Routemap DRAFT 2 Policy Analysis International Context A policy analysis was conducted to Paris Agreement and the Nationally Determined Contributions (2016) determine which international, national and Description: The Paris Agreement sets out a global framework to regional policies support a transition to the limit global temperature rise below 2°C, with a target of 1.5°C in circular economy and what are best practice accordance with the recommendations of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Signed by 175 countries, including examples for the West Midlands region. the UK, it is the first legally binding global climate change agreement and came into force in November 2016. The circular economy is one United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (2015) method for countries to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions. Description: The United Nations (UN) set 17 goals for sustainable Focus on Circular Economy: Low development that were adopted by UN Member states in 2015. Impact: No significant impact on circular economy. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are intended to be achieved by 2030. SDG7 Affordable and Clean Energy, SDG8 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Fifth Decent Work and Economic Growth, SDG9 Industry, Innovation and Assessment Report AR5 (2018) Infrastructure, and SDG12 Responsible Consumption and Production are particularly relevant for the Circular Economy. Description: Since the Paris Agreement the IPCC have called for increased action to achieve net zero carbon by 2030, including Focus on Circular Economy: Medium placing a higher price on emissions, shifting investment patterns, Impact: Encourages consideration of circular economy concepts and accelerating the transition to renewable energy and enabling inter-connectivity with wider development goals. -

Foundation Priority Programmes South

Foundation Priority Programmes West Midlands South Thank you for your interest in the Foundation Priority Programmes available in WM South. We have 15 programmes available offering experience in Medical Education, Leadership and Digital Innovation. I hope you will find the information below helpful and hope to see you working in WM South in August 2021. Further information regarding Foundation Priority programmes, including the application process can be found on the UKFPO website https://foundationprogramme.nhs.uk/programmes/2-year- foundation-programme/foundation-priority-programme-2/ The following table give an overview of the programmes we are offering in WM South. Employing Organisation FPP Post and Incentives Hereford County Hospital, Wye Valley x3 Education Foundation Posts NHS Trust ➢ Postgraduate Certificate in Education at F2 ➢ 80% clinical and 20% education at F2 University Hospitals Coventry and x6 Leadership Foundation Posts Warwickshire (UHCW), George Eliot ➢ Linked to Leadership Programme Hospital and South Warwickshire NHS ➢ Quality Improvement Project (QIP) Foundation Trust ➢ Peer Support and Management ➢ Undertaken during the F2 year x6 Digital Health Innovation Posts ➢ Links with Local Universities ➢ Develop skills for Delivering Care in a Digital World ➢ Six Workshops, Evaluative Project and Mentoring ➢ Course Certificate and Associate Membership of Faculty of Clinical Informatics ➢ Undertaken during the F1 year Education Foundation posts – Wye Valley NHS Trust – Hereford Hospital Following successful completion of -

Empire and English Nationalismn

Nations and Nationalism 12 (1), 2006, 1–13. r ASEN 2006 Empire and English nationalismn KRISHAN KUMAR Department of Sociology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, USA Empire and nation: foes or friends? It is more than pious tribute to the great scholar whom we commemorate today that makes me begin with Ernest Gellner. For Gellner’s influential thinking on nationalism, and specifically of its modernity, is central to the question I wish to consider, the relation between nation and empire, and between imperial and national identity. For Gellner, as for many other commentators, nation and empire were and are antithetical. The great empires of the past belonged to the species of the ‘agro-literate’ society, whose central fact is that ‘almost everything in it militates against the definition of political units in terms of cultural bound- aries’ (Gellner 1983: 11; see also Gellner 1998: 14–24). Power and culture go their separate ways. The political form of empire encloses a vastly differ- entiated and internally hierarchical society in which the cosmopolitan culture of the rulers differs sharply from the myriad local cultures of the subordinate strata. Modern empires, such as the Soviet empire, continue this pattern of disjuncture between the dominant culture of the elites and the national or ethnic cultures of the constituent parts. Nationalism, argues Gellner, closes the gap. It insists that the only legitimate political unit is one in which rulers and ruled share the same culture. Its ideal is one state, one culture. Or, to put it another way, its ideal is the national or the ‘nation-state’, since it conceives of the nation essentially in terms of a shared culture linking all members. -

A Science & Innovation Audit for the West Midlands

A Science & Innovation Audit for the West Midlands June 2017 A Science & Innovation Audit for the West Midlands Contents Foreword 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 1 2. Economic and research landscape .................................................................................... 4 3. The West Midlands SIA Framework ................................................................................. 15 4. Innovation Ecosystem ....................................................................................................... 18 5. Enabling Competencies .................................................................................................... 38 6. Market Strengths ................................................................................................................ 49 7. Key findings and moving forward .................................................................................... 73 Annex A: Case Studies ........................................................................................................ A-1 www.sqw.co.uk A Science & Innovation Audit for the West Midlands Foreword In a year of change and challenge on other fronts, this last year has also been one of quiet revolution. This year has seen a dramatic increase across the UK in the profile of science and innovation as a key driver of productivity and its potential to improve the way our public services are delivered. The potential has always -

West Midlands European Regional Development Fund Operational Programme

Regional Competitiveness and Employment Objective 2007 – 2013 West Midlands European Regional Development Fund Operational Programme Version 3 July 2012 CONTENTS 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 – 5 2a SOCIO-ECONOMIC ANALYSIS - ORIGINAL 2.1 Summary of Eligible Area - Strengths and Challenges 6 – 14 2.2 Employment 15 – 19 2.3 Competition 20 – 27 2.4 Enterprise 28 – 32 2.5 Innovation 33 – 37 2.6 Investment 38 – 42 2.7 Skills 43 – 47 2.8 Environment and Attractiveness 48 – 50 2.9 Rural 51 – 54 2.10 Urban 55 – 58 2.11 Lessons Learnt 59 – 64 2.12 SWOT Analysis 65 – 70 2b SOCIO-ECONOMIC ANALYSIS – UPDATED 2010 2.1 Summary of Eligible Area - Strengths and Challenges 71 – 83 2.2 Employment 83 – 87 2.3 Competition 88 – 95 2.4 Enterprise 96 – 100 2.5 Innovation 101 – 105 2.6 Investment 106 – 111 2.7 Skills 112 – 119 2.8 Environment and Attractiveness 120 – 122 2.9 Rural 123 – 126 2.10 Urban 127 – 130 2.11 Lessons Learnt 131 – 136 2.12 SWOT Analysis 137 - 142 3 STRATEGY 3.1 Challenges 143 - 145 3.2 Policy Context 145 - 149 3.3 Priorities for Action 150 - 164 3.4 Process for Chosen Strategy 165 3.5 Alignment with the Main Strategies of the West 165 - 166 Midlands 3.6 Development of the West Midlands Economic 166 Strategy 3.7 Strategic Environmental Assessment 166 - 167 3.8 Lisbon Earmarking 167 3.9 Lisbon Agenda and the Lisbon National Reform 167 Programme 3.10 Partnership Involvement 167 3.11 Additionality 167 - 168 4 PRIORITY AXES Priority 1 – Promoting Innovation and Research and Development 4.1 Rationale and Objective 169 - 170 4.2 Description of Activities -

LANGUAGE VARIETY in ENGLAND 1 ♦ Language Variety in England

LANGUAGE VARIETY IN ENGLAND 1 ♦ Language Variety in England One thing that is important to very many English people is where they are from. For many of us, whatever happens to us in later life, and however much we move house or travel, the place where we grew up and spent our childhood and adolescence retains a special significance. Of course, this is not true of all of us. More often than in previous generations, families may move around the country, and there are increasing numbers of people who have had a nomadic childhood and are not really ‘from’ anywhere. But for a majority of English people, pride and interest in the area where they grew up is still a reality. The country is full of football supporters whose main concern is for the club of their childhood, even though they may now live hundreds of miles away. Local newspapers criss-cross the country in their thousands on their way to ‘exiles’ who have left their local areas. And at Christmas time the roads and railways are full of people returning to their native heath for the holiday period. Where we are from is thus an important part of our personal identity, and for many of us an important component of this local identity is the way we speak – our accent and dialect. Nearly all of us have regional features in the way we speak English, and are happy that this should be so, although of course there are upper-class people who have regionless accents, as well as people who for some reason wish to conceal their regional origins. -

The Story of New Jersey

THE STORY OF NEW JERSEY HAGAMAN THE UNIVERSITY PUBLISHING COMPANY Examination Copy THE STORY OF NEW JERSEY (1948) A NEW HISTORY OF THE MIDDLE ATLANTIC STATES THE STORY OF NEW JERSEY is for use in the intermediate grades. A thorough story of the Middle Atlantic States is presented; the context is enriohed with illustrations and maps. THE STORY OF NEW JERSEY begins with early Indian Life and continues to present day with glimpses of future growth. Every aspect from mineral resources to vac-| tioning areas are discussed. 160 pages. Vooabulary for 4-5 Grades. List priceJ $1.28 Net price* $ .96 (Single Copy) (5 or more, f.o.b. i ^y., point of shipment) i^c' *"*. ' THE UNIVERSITY PUBLISHING COMPANY Linooln, Nebraska ..T" 3 6047 09044948 8 lererse The Story of New Jersey BY ADALINE P. HAGAMAN Illustrated by MARY ROYT and GEORGE BUCTEL The University Publishing Company LINCOLN NEW YORK DALLAS KANSAS CITY RINGWOOD PUBLIC LIBRARY 145 Skylands Road Ringwood, New Jersey 07456 TABLE OF CONTENTS NEW.JERSEY IN THE EARLY DAYS Before White Men Came ... 5 Indian Furniture and Utensils 19 Indian Tribes in New Jersey 7 Indian Food 20 What the Indians Looked Like 11 Indian Money 24 Indian Clothing 13 What an Indian Boy Did... 26 Indian Homes 16 What Indian Girls Could Do 32 THE WHITE MAN COMES TO NEW JERSEY The Voyage of Henry Hudson 35 The English Take New Dutch Trading Posts 37 Amsterdam 44 The Colony of New The English Settle in New Amsterdam 39 Jersey 47 The Swedes Come to New New Jersey Has New Jersey 42 Owners 50 PIONEER DAYS IN NEW JERSEY Making a New Home 52 Clothing of the Pioneers .. -

Disunited Kingdom?

DISUNITED KINGDOM? ATTITUDES TO THE EU ACROSS THE UK Rachel Ormston Head of Social Attitudes at NatCen Social Research Disunited kingdom? Attitudes to the EU across the UK This paper examines the nature and scale of differences in support for the European Union across the four constituent countries of the UK. It assesses how far apart opinion in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland appears to be. It reviews the current state of the polls in each country and what this suggests about whose views might determine the outcome of the referendum. Finally, it examines potential reasons for the variation between England, Scotland and Wales in the level of support for EU membership, including differences in demographic profile, party structure and national identity. FAR FROM UNITED ON EUROPE Although recent poll and survey data suggests a slight majority favour remaining in the EU, the size of this majority is much narrower in England than in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. 52% 55% 64% 75% Figures based on mean of recent polls 2 DISUNITED KINGDOM? ATTITUDES TO THE EU ACROSS THE UK PARTY POLITICS AND PUBLIC OPINION England’s relatively anti-EU mood reflects the relatively high level of support for (anti-EU) UKIP and (partly Eurosceptic) Conservatives. LEAVE REMAIN UKIP SNP LABOUR LIBERAL PLAID CYMRU CONSERVATIVE DEMOCRATS AN ENGLISH REFERENDUM? Within England, people who feel particularly strongly English are the most likely to want Britain to leave the EU. LEAVE! DISUNITED KINGDOM? ATTITUDES TO THE EU ACROSS THE UK 3 INTRODUCTION From the perspective of 2015, constant constitutional wrangling seems to have become the norm in the UK. -

A Guide to English Culture and Customs

A GUIDE TO ENGLISH CULTURE AND CUSTOMS This document has been prepared for you to read before you leave for England, and to refer to during your time there. It gives you information about English customs and describes some points that may be different from your own culture. Part of the fun of coming to live or study in another country is observing and learning about the culture and customs of its people. We don’t want to spoil the surprise for you but we do understand that it can be useful to know how other people will expect you to behave, and will behave towards you whilst you’re away from home. This can avoid awkward misunderstandings for both you and the people you meet and make friends with! We hope that your stay in England will be thoroughly enjoyable and we very much look forward to welcoming you at St Giles College. Queues – The English are famous for being very polite. Always join the back of the queue and wait your turn when buying tickets, waiting in a bank, post office or for a bus or train. If you ‘jump the queue’ in England you are known as a ‘queue jumper’ and although people may not say anything to you, they will make very unhappy noises! If there is any confusion about whether there is one queue or more for several different cashiers, you should still wait your turn and stay behind everyone who arrived before you. English people do not try to get to the front first; they are very fair. -

English Society 1660±1832

ENGLISH SOCIETY 1660±1832 Religion, ideology and politics during the ancien regime J. C. D. CLARK published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, UK www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011±4211, USA www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia Ruiz de AlarcoÂn 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain # Cambridge University Press 2000 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published as English Society 1688±1832,1985. Second edition, published as English Society 1660±1832 ®rst published 2000. Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Baskerville 11/12.5 pt. System 3b2[ce] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data Clark, J. C. D. English society, 1660±1832 : religion, ideology, and politics during the ancien regime/J.C.D.Clark. p. cm. Rev. edn of: English society, 1688±1832. 1985. Includes index. isbn 0 521 66180 3 (hbk) ± isbn 0 521 66627 9 (pbk) 1. Great Britain ± Politics and government ± 1660±1714. 2. Great Britain ± Politics and government ± 18th century. 3. Great Britain ± Politics and government ± 1800±1837. 4. Great Britain ± Social conditions. i.Title. ii.Clark,J.C.D.Englishsociety,1688±1832. -

Refugees in Europe, 1919–1959 Iii Refugees in Europe, 1919–1959

Refugees in Europe, 1919–1959 iii Refugees in Europe, 1919–1959 A Forty Years’ Crisis? Edited by Matthew Frank and Jessica Reinisch Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc LONDON • OXFORD • NEW YORK • NEW DELHI • SYDNEY Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2017 © Matthew Frank, Jessica Reinisch and Contributors, 2017 This work is published subject to a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Licence. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the authors. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: HB: 978-1-4725-8562-2 ePDF: 978-1-4725-8564-6 eBook: 978-1-4725-8563-9 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. Cover image © LAPI/Roger Viollet/Getty Images Typeset by Deanta Global Publishing Services, Chennai, India To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com. Here you will find extracts, author interviews, details of forthcoming events and the -

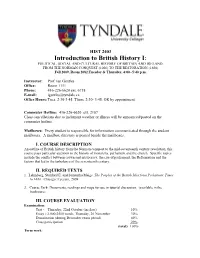

Introduction to British History I

HIST 2403 Introduction to British History I: POLITICAL, SOCIAL AND CULTURAL HISTORY OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND, FROM THE NORMAN CONQUEST (1066) TO THE RESTORATION (1660) Fall 2009, Room 2082,Tuesday & Thursday, 4:00--5:40 p.m. Instructor: Prof. Ian Gentles Office: Room 1111 Phone: 416-226-6620 ext. 6718 E-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Tues. 2:30-3:45, Thurs. 2:30- 3:45, OR by appointment Commuter Hotline: 416-226-6620 ext. 2187 Class cancellations due to inclement weather or illness will be announced/posted on the commuter hotline. Mailboxes: Every student is responsible for information communicated through the student mailboxes. A mailbox directory is posted beside the mailboxes. I. COURSE DESCRIPTION An outline of British history from the Norman conquest to the mid-seventeenth century revolution, this course pays particular attention to the history of monarchy, parliament and the church. Specific topics include the conflict between crown and aristocracy, the rise of parliament, the Reformation and the factors that led to the turbulence of the seventeenth century. II. REQUIRED TEXTS 1. Lehmberg, Stanford E. and Samantha Meigs. The Peoples of the British Isles from Prehistoric Times to 1688 . Chicago: Lyceum, 2009 2. Course Pack: Documents, readings and maps for use in tutorial discussion. (available in the bookstore) III. COURSE EVALUATION Examination : Test - Thursday, 22nd October (in class) 10% Essay - 2,000-2500 words, Thursday, 26 November 30% Examination (during December exam period) 40% Class participation 20% (total) 100% Term work : a. You are expected to attend the tutorials, preparing for them through the lectures and through assigned reading.