Beyond Class?1 Social Structures and Social Perceptions in Modern England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring 2018 Celebrating Our 45Th

Celebrating our 45th Anniversary, p. 2 Stowe Restoration Project, pgs. 3-4 The Trevelyans of Wallington Hall, pgs. 5-6 Spring 2018 1 | From the Executive Director Dear Members & Friends, THE ROYAL OAK FOUNDATION 20 West 44th Street, Suite 606 New York, New York 10036-6603 2018 marks Royal Oak’s 45th Anniversary. We Churchill’s studio at Chartwell give tangible 212.480.2889 | www.royal-oak.org will celebrate this in many ways—more with a expression to the many new interpretive focus on where we are as an organization today programs that will excite visitors daily just as and what we hope for in the future. the exhibition did 35 years ago. BOARD OF DIRECTORS Honorary Chairman In reviewing some of the histories of Royal Other big news for 2018 is our appeal to help Mrs. Henry J. Heinz II Oak, I was surprised to find an event in 1983 the National Trust finish off a multi-year and Chairman that was noted as pivotal in transforming multi-task restoration effort for Stowe. Stowe Lynne L. Rickabaugh the Foundation’s relationship is one of the leading garden and Vice Chairman with the Trust from one of just landscape properties in England Prof. Susan S. Samuelson growing ‘friendship’ to one of a and has a wide significance in Treasurer serious fundraising partnership. the history of garden design in Renee Nichols Tucei The connections of this historic Europe, Russia and America (see Secretary event with what Royal Oak has pages 3-4). It is among the most Thomas M. Kelly more recently accomplished and visited Trust properties. -

Guidance on the Use of Royal Arms, Names and Images

GUIDANCE ON THE USE OF ROYAL ARMS, NAMES AND IMAGES 1 The following booklet summarises the legal position governing the use, for commercial purposes, of the Royal Arms, Royal Devices, Emblems and Titles and of photographs, portraits, engravings, effigies and busts of The Queen and Members of the Royal Family. Guidance on advertising in which reference is made to a Member of the Royal Family, and on the use of images of Members of the Royal Family on articles for sale, is also provided. The Lord Chamberlain’s Office will be pleased to provide guidance when it is unclear as to whether the use of “Arms” etc., may give the impression that there is a Royal connection. 2 TRADE MARKS Section 4 (1) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 states: “A trade mark which consists of or contains – (a) the Royal arms, or any of the principal armorial bearings of the Royal arms, or any insignia or device so nearly resembling the Royal arms or any such armorial bearing as to be likely to be mistaken for them or it, (b) a representation of the Royal crown or any of the Royal flags, (c) a representation of Her Majesty or any Member of the Royal Family, or any colourable imitation thereof, or (d) words, letters or devices likely to lead persons to think that the applicant either has or recently has had Royal patronage or authorisation, shall not be registered unless it appears to the registrar that consent has been given by or on behalf of Her Majesty or, as the case may be, the relevant Member of the Royal Family.” The Lord Chamberlain's Office is empowered to grant the consent referred to in Section 4(1) on behalf of Her Majesty The Queen. -

Sample Intercessions for Atonement & Healing

Diocese of Scranton Sample Intercessions for Atonement & Healing From the Federation of Diocesan Liturgical Commissions and the Diocese of Scranton Office for Parish Life It is recommended to include at least one of these intercessions in the Universal Prayer each weekend. 1. For the victims of abuse at the hands of some members of the clergy, may they find healing, support, and peace within the Catholic community, we pray to the Lord. 2. For the families of abuse victims, that their compassionate concern may affect healing and that their strong advocacy may bring about change within the Church and society, we pray to the Lord. 3. For Pope Francis, for the bishops of the United States, and all the bishops of the world, that they may heed the promptings of the Holy Spirit and work to promote justice for all victims of sexual abuse, we pray to the Lord. 4. That those terrorized by sexual abuse, especially those abused by priests of our Diocese, may find the courage to come forward to authorities and find the peace and consolation they need, we pray to the Lord. 5. That the Church may be a safe refuge for all in need, especially those who suffer physical, mental and sexual abuse, we pray to the Lord. 6. That all members of the Church may commit themselves to protect children and the most vulnerable in our communities, we pray to the Lord. 7. For all those in parishes and dioceses who are responsible for safe environment training programs which promote the protection of children, we pray to the Lord. -

Some Pages from the Book

AF Whats Mine is Yours.indb 2 16/3/21 18:49 What’s Mine Is Yours Private Collectors and Public Patronage in the United States Essays in Honor of Inge Reist edited by Esmée Quodbach AF Whats Mine is Yours.indb 3 16/3/21 18:49 first published by This publication was organized by the Center for the History of Collecting at The Frick Collection and Center for the History of Collecting Frick Art Reference Library, New York, the Centro Frick Art Reference Library, The Frick Collection de Estudios Europa Hispánica (CEEH), Madrid, and 1 East 70th Street the Center for Spain in America (CSA), New York. New York, NY 10021 José Luis Colomer, Director, CEEH and CSA Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica Samantha Deutch, Assistant Director, Center for Felipe IV, 12 the History of Collecting 28014 Madrid Esmée Quodbach, Editor of the Volume Margaret Laster, Manuscript Editor Center for Spain in America Isabel Morán García, Production Editor and Coordinator New York Laura Díaz Tajadura, Color Proofing Supervisor John Morris, Copyeditor © 2021 The Frick Collection, Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica, and Center for Spain in America PeiPe. Diseño y Gestión, Design and Typesetting Major support for this publication was provided by Lucam, Prepress the Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica (CEEH) Brizzolis, Printing and the Center for Spain in America (CSA). Library of Congress Control Number: 2021903885 ISBN: 978-84-15245-99-5 Front cover image: Charles Willson Peale DL: M-5680-2021 (1741–1827), The Artist in His Museum. 1822. Oil on canvas, 263.5 × 202.9 cm. -

Brexit-Tales from a Divided Country: Fragmented Nationalism in Anthony Cartwright’S the Cut, Amanda Craig’S the Lie of the Land, and Jonathan Coe’S Middle England

Brexit-Tales from a Divided Country: Fragmented Nationalism in Anthony Cartwright’s The Cut, Amanda Craig’s The Lie of the Land, and Jonathan Coe’s Middle England Emma Linders, S2097052 Master thesis: Literary Studies, Literature in Society: Europe and Beyond University of Leiden Supervisor: Prof. Dr. P.T.M.G. Liebregts Second reader: Dr. M.S. Newton Date: 01-02-2020 (Zaichenko) Emma Linders 2 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 3 CHAPTER 1 – Strangers in a Familiar Land: National divisions in Anthony Cartwright’s The Cut ......... 10 Outsider Perspective ......................................................................................................................... 10 Personification .................................................................................................................................. 11 Demographic Divides ........................................................................................................................ 11 Foreign Home Nation ........................................................................................................................ 13 Class Society ...................................................................................................................................... 14 Geography ......................................................................................................................................... 16 Language -

![Notes for the Guidance of Rep Dls Re Borough Observance of Mourning Following the Death of a Member of the Royal Family [Not Including the Sovereign]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6001/notes-for-the-guidance-of-rep-dls-re-borough-observance-of-mourning-following-the-death-of-a-member-of-the-royal-family-not-including-the-sovereign-766001.webp)

Notes for the Guidance of Rep Dls Re Borough Observance of Mourning Following the Death of a Member of the Royal Family [Not Including the Sovereign]

Notes for the Guidance of Rep DLs re Borough Observance of Mourning Following the Death of a Member of the Royal Family [not including the Sovereign] The forms of Mourning are: NATIONAL MOURNING ROYAL MOURNING Following the death of a Member of The Royal Family, the Lord Chamberlain or the Earl Marshal will consult with the Prime Minister before seeking The Sovereign’s Commands with regard to mourning. No action should be taken until there is a formal announcement of the death (that is, when the media reports that Buckingham Palace or Downing Street has announced the death, not when they indicate that “reports are coming in of the death of …..”). National Mourning Observed by all, including national representatives serving abroad. Flags lowered from the day of death to the day of Funeral. Business/Sporting activities considered by Prime Minister’s Office. Royal Mourning Observed by Members of the Royal Family, Households of the Royal Family and Troops on Public Duties. Flags Flags should be flown at half-mast on the day the death is announced (or immediately following) and day of Funeral. Flags also lowered on any other occasions where Her Majesty has given special command. Half-mast means the flag is flown two-thirds of the way up the flagpole with at least the height of the flag between the top of the flag and the top of the flagpole. On flag poles that are more than 45o from the vertical, flags cannot be flown at half-mast and the pole should be left empty. When a flag is to be flown at half-mast it should first be raised all the way to the top of the mast, allowed to remain there for a second and then lowered to the half-mast position. -

Lift up Your Hearts. All: We Lift Them up to the Lord. Priest

Priest: The Lord be with you. CONGREGATION’S PRAYER CARD All: And with your spirit. NEW RESPONSES AT MASS Priest: Lift up your hearts. All: We lift them up to the Lord. (Changes are indicated in bold type.) Priest: Let us give thanks to the Lord our God. All: It is right and just. THE GREETING Priest: In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. Holy, Holy, Holy Lord God of hosts. All: Amen. Heaven and earth are full of your glory. Priest: The Lord be with you. Hosanna in the highest. All: And with your spirit. Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord. Hosanna in the highest. PENITENTIAL ACT A All: I confess to almighty God and to you, my brothers and sisters, Priest: The mystery of faith. that I have greatly sinned, in my thoughts and in my words, All: We proclaim your death, O Lord, and profess your in what I have done and in what I have failed to do, Resurrection until you come again. Striking your breast as you say: through my fault, Or When we eat this Bread and drink this Cup, through my fault, we proclaim your death, O Lord, until you come again. through my most grievous fault; therefore I ask blessed Mary ever-Virgin, Or Save us Saviour of the world, for by your Cross and all the Angels and Saints, and you, my brothers and sisters, Resurrection, you have set us free. to pray for me to the Lord our God. -

The Oxford Companion to English Literature, 6Th Edition

e cabal, from the Hebrew word qabbalah, a secret an elderly man. He is said by *Bede to have been an intrigue of a sinister character formed by a small unlearned herdsman who received suddenly, in a body of persons; or a small body of persons engaged in vision, the power of song, and later put into English such an intrigue; in British history applied specially to verse passages translated to him from the Scriptures. the five ministers of Charles II who signed the treaty of The name Caedmon cannot be explained in English, alliance with France for war against Holland in 1672; and has been conjectured to be Celtic (an adaptation of these were Clifford, Arlington, *Buckingham, Ashley the British Catumanus). In 1655 François Dujon (see SHAFTESBURY, first earl of), and Lauderdale, the (Franciscus Junius) published at Amsterdam from initials of whose names thus arranged happened to the unique Bodleian MS Junius II (c.1000) long scrip form the word 'cabal' [0£D]. tural poems, which he took to be those of Casdmon. These are * Genesis, * Exodus, *Daniel, and * Christ and Cade, Jack, Rebellion of, a popular revolt by the men of Satan, but they cannot be the work of Caedmon. The Kent in June and July 1450, Yorkist in sympathy, only work which can be attributed to him is the short against the misrule of Henry VI and his council. Its 'Hymn of Creation', quoted by Bede, which survives in intent was more to reform political administration several manuscripts of Bede in various dialects. than to create social upheaval, as the revolt of 1381 had attempted. -

English Society 1660±1832

ENGLISH SOCIETY 1660±1832 Religion, ideology and politics during the ancien regime J. C. D. CLARK published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, UK www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011±4211, USA www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia Ruiz de AlarcoÂn 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain # Cambridge University Press 2000 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published as English Society 1688±1832,1985. Second edition, published as English Society 1660±1832 ®rst published 2000. Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Baskerville 11/12.5 pt. System 3b2[ce] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data Clark, J. C. D. English society, 1660±1832 : religion, ideology, and politics during the ancien regime/J.C.D.Clark. p. cm. Rev. edn of: English society, 1688±1832. 1985. Includes index. isbn 0 521 66180 3 (hbk) ± isbn 0 521 66627 9 (pbk) 1. Great Britain ± Politics and government ± 1660±1714. 2. Great Britain ± Politics and government ± 18th century. 3. Great Britain ± Politics and government ± 1800±1837. 4. Great Britain ± Social conditions. i.Title. ii.Clark,J.C.D.Englishsociety,1688±1832. -

(Title of the Thesis)*

TENDENCIA THATCHERITIS OR ENGLISHNESS REMADE The Fictions of Julian Barnes, Hanif Kureishi and Pat Barker by Heather Ann Joyce A thesis submitted to the Department of English In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen‘s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (July, 2011) Copyright © Heather Ann Joyce, 2011 Abstract Julian Barnes, Pat Barker, and Hanif Kureishi are all canonical authors whose fictions are widely believed to reflect the cultural and political state of a nation that is post-war, post-imperial and post-modern. While much has been written on how Barker‘s and Kureishi‘s early works in particular respond to and intervene in the presiding political narrative of the 1980s – Thatcherism – treatment of how revenants of Thatcherism have shaped these writers‘ works from 1990 on has remained cursory. Thatcherism is more than an obvious historical reference point for Barker, Barnes, and Kureishi; their works demonstrate a sophisticated understanding of how Thatcher‘s reworkings of the repertoires of Englishness – a representational as well as political and cultural endeavour – persist beyond her time in office. Barnes, Barker, and Kureishi seem to have reached the same conclusion as political and cultural critics: Thatcher and Thatcherism have remade not only the contemporary political and cultural landscapes but also the electorate and consequently the English themselves. Tony Blair‘s conception of the New Britain proved less than satisfactory because contemporary repertoires of Englishness repeat and rework historical and not incidentally imperial formulations of England and Englishness rather than envision civic and populist formulations of renewal. Barnes‘s England, England and Arthur & George confront the discourse of inevitability that has come to be attached to contemporary formulations of both political and cultural Englishness – both in terms of its predictable demise and its belated celebration. -

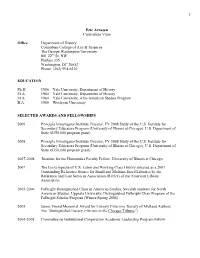

Arnesen CV GWU Website June 2009

1 Eric Arnesen Curriculum Vitae Office Department of History Columbian College of Arts & Sciences The George Washington University 801 22nd St. NW Phillips 335 Washington, DC 20052 Phone: (202) 994-6230 EDUCATION Ph.D. 1986 Yale University, Department of History M.A. 1984 Yale University, Department of History M.A. 1984 Yale University, Afro-American Studies Program B.A. 1980 Wesleyan University SELECTED AWARDS AND FELLOWSHIPS 2009 Principle Investigator/Institute Director, FY 2008 Study of the U.S. Institute for Secondary Educators Program (University of Illinois at Chicago), U.S. Department of State ($350,000 program grant) 2008 Principle Investigator/Institute Director, FY 2008 Study of the U.S. Institute for Secondary Educators Program (University of Illinois at Chicago), U.S. Department of State ($350,000 program grant) 2007-2008 Institute for the Humanities Faculty Fellow, University of Illinois at Chicago 2007 The Encyclopedia of U.S. Labor and Working Class History selected as a 2007 Outstanding Reference Source for Small and Medium-Sized Libraries by the Reference and User Services Association (RUSA) of the American Library Association. 2005-2006 Fulbright Distinguished Chair in American Studies, Swedish Institute for North American Studies, Uppsala University, Distinguished Fulbright Chair Program of the Fulbright Scholar Program (Winter-Spring 2006) 2005 James Friend Memorial Award for Literary Criticism, Society of Midland Authors (for “distinguished literary criticism in the Chicago Tribune”) 2004-2005 Committee on Institutional -

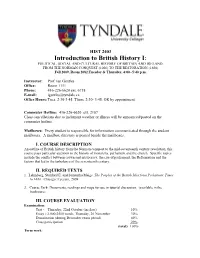

Introduction to British History I

HIST 2403 Introduction to British History I: POLITICAL, SOCIAL AND CULTURAL HISTORY OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND, FROM THE NORMAN CONQUEST (1066) TO THE RESTORATION (1660) Fall 2009, Room 2082,Tuesday & Thursday, 4:00--5:40 p.m. Instructor: Prof. Ian Gentles Office: Room 1111 Phone: 416-226-6620 ext. 6718 E-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Tues. 2:30-3:45, Thurs. 2:30- 3:45, OR by appointment Commuter Hotline: 416-226-6620 ext. 2187 Class cancellations due to inclement weather or illness will be announced/posted on the commuter hotline. Mailboxes: Every student is responsible for information communicated through the student mailboxes. A mailbox directory is posted beside the mailboxes. I. COURSE DESCRIPTION An outline of British history from the Norman conquest to the mid-seventeenth century revolution, this course pays particular attention to the history of monarchy, parliament and the church. Specific topics include the conflict between crown and aristocracy, the rise of parliament, the Reformation and the factors that led to the turbulence of the seventeenth century. II. REQUIRED TEXTS 1. Lehmberg, Stanford E. and Samantha Meigs. The Peoples of the British Isles from Prehistoric Times to 1688 . Chicago: Lyceum, 2009 2. Course Pack: Documents, readings and maps for use in tutorial discussion. (available in the bookstore) III. COURSE EVALUATION Examination : Test - Thursday, 22nd October (in class) 10% Essay - 2,000-2500 words, Thursday, 26 November 30% Examination (during December exam period) 40% Class participation 20% (total) 100% Term work : a. You are expected to attend the tutorials, preparing for them through the lectures and through assigned reading.