The Development of the Railway Network in Britain 1825-19111 Leigh Shaw-Taylor and Xuesheng You 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kentucky in the 1880S: an Exploration in Historical Demography Thomas R

The Kentucky Review Volume 3 | Number 2 Article 5 1982 Kentucky in the 1880s: An Exploration in Historical Demography Thomas R. Ford University of Kentucky Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kentucky-review Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Ford, Thomas R. (1982) "Kentucky in the 1880s: An Exploration in Historical Demography," The Kentucky Review: Vol. 3 : No. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kentucky-review/vol3/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Kentucky Libraries at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Kentucky Review by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kentucky in the 1880s: An Exploration in Historical Demography* e c Thomas R. Ford r s F t.; ~ The early years of a decade are frustrating for social demographers t. like myself who are concerned with the social causes and G consequences of population changes. Social data from the most recent census have generally not yet become available for analysis s while those from the previous census are too dated to be of current s interest and too recent to have acquired historical value. That is c one of the reasons why, when faced with the necessity of preparing c a scholarly lecture in my field, I chose to stray a bit and deal with a historical topic. -

Great Western Railway Ships - Wikipedi… Great Western Railway Ships from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

5/20/2011 Great Western Railway ships - Wikipedi… Great Western Railway ships From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Great Western Railway’s ships operated in Great Western Railway connection with the company's trains to provide services to (shipping services) Ireland, the Channel Islands and France.[1] Powers were granted by Act of Parliament for the Great Western Railway (GWR) to operate ships in 1871. The following year the company took over the ships operated by Ford and Jackson on the route between Wales and Ireland. Services were operated between Weymouth, the Channel Islands and France on the former Weymouth and Channel Islands Steam Packet Company routes. Smaller GWR vessels were also used as tenders at Plymouth and on ferry routes on the River Severn and River Dart. The railway also operated tugs and other craft at their docks in Wales and South West England. The Great Western Railway’s principal routes and docks Contents Predecessor Ford and Jackson Successor British Railways 1 History 2 Sea-going ships Founded 1871 2.1 A to G Defunct 1948 2.2 H to O Headquarters Milford/Fishguard, Wales 2.3 P to R 2.4 S Parent Great Western Railway 2.5 T to Z 3 River ferries 4 Tugs and work boats 4.1 A to M 4.2 N to Z 5 Colours 6 References History Isambard Kingdom Brunel, the GWR’s chief engineer, envisaged the railway linking London with the United States of America. He was responsible for designing three large ships, the SS Great Western (1837), SS Great Britain (1843; now preserved at Bristol), and SS Great Eastern (1858). -

The Carrying Trade and the First Railways in England, C1750-C1850

The Carrying Trade and the First Railways in England, c1750-c1850 Carolyn Dougherty PhD University of York Railway Studies November 2018 Abstract Transport and economic historians generally consider the change from moving goods principally on roads, inland waterways and coastal ships to moving them principally on railways as inevitable, unproblematic, and the result of technological improvements. While the benefits of rail travel were so clear that most other modes of passenger transport disappeared once rail service was introduced, railway goods transport did not offer as obvious an improvement over the existing goods transport network, known as the carrying trade. Initially most railways were open to the carrying trade, but by the 1840s railway companies began to provide goods carriage and exclude carriers from their lines. The resulting conflict over how, and by whom, goods would be transported on railways, known as the carrying question, lasted more than a decade, and railway companies did not come to dominate domestic goods carriage until the 1850s. In this study I develop a fuller picture of the carrying trade than currently exists, highlighting its multimodal collaborative structure and setting it within the ‘sociable economy’ of late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century England. I contrast this economy with the business model of joint-stock companies, including railway companies, and investigate responses to the business practices of these companies. I analyse the debate over railway company goods carriage, and identify changes in goods transport resulting from its introduction. Finally, I describe the development and outcome of the carrying question, showing that railway companies faced resistance to their attempts to control goods carriage on rail lines not only from the carrying trade but also from customers of goods transport, the government and the general public. -

Download the Report Item 4

BOROUGH COUNCIL OF WELLINGBOROUGH AGENDA ITEM 4 Development Committee 17 February 2020 Report of the Principal Planning Manager Local listing of the Roundhouse and proposed Article 4 Direction 1 Purpose of report For the committee to consider and approve the designation of the Roundhouse (or number 2 engine shed) as a locally listed building and for the committee to also approve an application for the addition of an Article 4(1) direction to the building in order to remove permitted development rights and prevent unauthorised demolition. 2 Executive summary 2.1 The Roundhouse is a railway locomotive engine shed built in 1872 by the Midland Railway. There is some concern locally that the building could be demolished and should be protected. It was not considered by English Heritage to be worthy of national listing but it is considered by the council to be worthy of local listing. 2.2 Local listing does not protect the building from demolition but is a material consideration in a planning application. 2.3 An article 4(1) direction would be required to be in place to remove the permitted development rights of the owner. In this case it would require the owner to seek planning permission for the partial or total demolition of the building. 3 Appendices Appendix 1 – Site location plan Appendix 2 – Photos of site Appendix 3 – Historic mapping Appendix 4 – Historic England report for listing Appendix 5 – Local list criteria 4 Proposed action: 4.1 The committee is invited to APPROVE that the Roundhouse is locally listed and to APPROVE that an article 4 (1) direction can be made. -

Empire and English Nationalismn

Nations and Nationalism 12 (1), 2006, 1–13. r ASEN 2006 Empire and English nationalismn KRISHAN KUMAR Department of Sociology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, USA Empire and nation: foes or friends? It is more than pious tribute to the great scholar whom we commemorate today that makes me begin with Ernest Gellner. For Gellner’s influential thinking on nationalism, and specifically of its modernity, is central to the question I wish to consider, the relation between nation and empire, and between imperial and national identity. For Gellner, as for many other commentators, nation and empire were and are antithetical. The great empires of the past belonged to the species of the ‘agro-literate’ society, whose central fact is that ‘almost everything in it militates against the definition of political units in terms of cultural bound- aries’ (Gellner 1983: 11; see also Gellner 1998: 14–24). Power and culture go their separate ways. The political form of empire encloses a vastly differ- entiated and internally hierarchical society in which the cosmopolitan culture of the rulers differs sharply from the myriad local cultures of the subordinate strata. Modern empires, such as the Soviet empire, continue this pattern of disjuncture between the dominant culture of the elites and the national or ethnic cultures of the constituent parts. Nationalism, argues Gellner, closes the gap. It insists that the only legitimate political unit is one in which rulers and ruled share the same culture. Its ideal is one state, one culture. Or, to put it another way, its ideal is the national or the ‘nation-state’, since it conceives of the nation essentially in terms of a shared culture linking all members. -

A Forgotten Landscape

Crossing the Severn A Forgotten Landscape School Learning Resources Crossing the Severn Objectives :- To describe how people and animals have crossed the river Severn in the past and present. To create, design and build an innovative way of crossing the Severn. School Learning Resources Under and Over Under and Over - Tiny water voles burrow under the reens that drain the forgotten landscape and the two Severn crossings carry thousands of people over the Severn every day. Starlings and sparrowhawks get a birds’ eye view of the estuary while fossils lie just underneath its surface. School Learning Resources Make your Severn crossing You are going to design and make a new innovative way to cross the river Severn. You need to use the materials provided to create a model of your design. Your model must be able to support the lego man across the river. When you have you model come back and test it. School Learning Resources Your design Look at the following slides and take inspiration from designs from the past, present and future. Think about whether you will go under or over the river, whether you will use the water or try to keep dry. School Learning Resources Over - Second Severn Crossing Over - Severn Bridge Under - The Severn Railway Tunnel School Learning Resources Severn Bridge The Severn Bridge is a suspension bridge, carrying the M48 across the river Severn and river Wye. It leaves Aust and arrives in Chepstow, via support in Beachley on a peninsula. The bridge replaced the Aust ferry in 1966, and was granted Grade 1 listed status in 1999. -

Emigration from Great Britain

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: International Migrations, Volume II: Interpretations Volume Author/Editor: Walter F. Willcox, editor Volume Publisher: NBER Volume ISBN: 0-87014-017-5 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/will31-1 Publication Date: 1931 Chapter Title: Emigration from Great Britain Chapter Author: C. E. Snow Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c5111 Chapter pages in book: (p. 237 - 260) PART III STUDIES OF NATIONALEMIGRATION CURRENTS CHAPTER IX EMIGRATION FROM GREAT BRITAIN.' By DR. C. E. SNOW. General Concerning emigration from Great Britain prior to 1815, only fragmentary statistics are available, for before that date no regular attempt was made to measure the outflow of population.For some years before the treaty of peace with France, under which Canada in 1763 became a colony of the United Kingdom, a certain number of emigrants from Great Britain to the British North Amer- ican colonies were reported, but no reliable figures are available. During the five years 1769—1774 there was an emigration, probably approaching 10,000 persons per annum,2 from Scotland to North America, and substantial numbers also left England for the same destination.It has been estimated by Johnson3 that during the first decade of the nineteenth century the annual emigration from the whole of the United Kingdom to the American Continent ex- ceeded 20,000 persons, the majority going from the Highlands of Scotland and from Ireland. Emigration can be considered from two distinct aspects: (a) from the point of view of the force attracting people to other countries; (b) from the point of view of the force expelling people from their own country. -

Government Policy During the British Railway Mania and the 1847 Commercial Crisis

Government Policy during the British Railway Mania and the 1847 Commercial Crisis Campbell, G. (2014). Government Policy during the British Railway Mania and the 1847 Commercial Crisis. In N. Dimsdale, & A. Hotson (Eds.), British Financial Crises Since 1825 (pp. 58-75). Oxford University Press. https://global.oup.com/academic/product/british-financial-crises-since-1825-9780199688661?cc=gb&lang=en& Published in: British Financial Crises Since 1825 Document Version: Peer reviewed version Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights Copyright 2014 OUP. This material was originally published in British Financial Crises since 1825 Edited by Nicholas Dimsdale and Anthony Hotson, and has been reproduced by permission of Oxford University Press. For permission to reuse this material, please visit http://global.oup.com/academic/rights. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:28. Sep. 2021 Government Policy during the British Railway Mania and 1847 Commercial Crisis Gareth Campbell, Queen’s University Management School, Queen's University Belfast, Belfast, BT7 1NN ([email protected]) *An earlier version of this paper was presented to Oxford University’s Monetary History Group. -

Stimson Mill Company Records Inventory Accession No: 2397-001

UNIVERSITY UBRARIES w UNIVERSITY of WASH INCTON Spe, ial Colle tions. Stimson Mill Company records Inventory Accession No: 2397-001 Special Collections Division University of Washington Libraries Box 352900 Seattle, Washington, 98195-2900 USA (206) 543-1929 This document forms part of the Guide to the Stimson Mill Company Records. To find out more about the history, context, arrangement, availability and restrictions on this collection, click on the following link: http://digital.lib.washington.edu/findingaids/permalink/StimsonMillCompany0050_2397/ Special Collections home page: http://www.lib.washington.edu/specialcollections/ Search Collection Guides: http://digital.lib.washington.edu/findingaids/search STIMSON MILL a:ffl>ANY RECX)RDS Accession No. 2397, 2397-2 CDNI'AINER Lisr Folders Dates Incoming Letters 1 1879 - 1882 2 1882 - 1884 3 1884 - 1885 4 1885 - 1886 5 1886 - 1887/88 6 1887/88 - 1889 7 1889 - 1890 8 1890/91 - 1891/92 9 1892 - 1893/94 10 1893/94 - 1900/04 11 Miscellaneous Family Correspondence Williard stimson T. D. stimson Jay stimson J.J. Fay Fred s. stimson Charles D. stimson Charles W. stimson to Willard H. sti.m.son F.state of Willard H. sti.m.son Madera Property Papers of Willard H. stimson F.state of Willard H. sti.m.son 1929 Tax statements for I.and ca. 1860-80 Miscellaneous Business Correspondence Business Papers: Washington and I.os Angeles Correspondence re: stimson Building, I.os Angeles-A-G 1904-12 Correspondence re: stimson Building, I.os Angeles--H-1 1902-12 Correspondence re: stimson Building, I.os Angeles--M-S 1902-14 Correspondence re: stimson Building, I.os Angeles-T-Z 1915-20 Miscellaneous Business Papers 12 stimson Company Time Books ca. -

Brunel's Dream

Global Foresights | Global Trends and Hitachi’s Involvement Brunel’s Dream Kenji Kato Industrial Policy Division, Achieving Comfortable Mobility Government and External Relations Group, Hitachi, Ltd. The design of Paddington Station’s glass roof was infl u- Renowned Engineer Isambard enced by the Crystal Palace building erected as the venue for Kingdom Brunel London’s fi rst Great Exhibition held in 1851. Brunel was also involved in the planning for Crystal Palace, serving on the The resigned sigh that passed my lips on arriving at Heathrow building committee of the Great Exhibition, and acclaimed Airport was prompted by the long queues at immigration. the resulting structure of glass and iron. Being the gateway to London, a city known as a melting pot Rather than pursuing effi ciency in isolation, Brunel’s of races, the arrivals processing area was jammed with travel- approach to constructing the Great Western Railway was to ers from all corners of the world; from Europe of course, but make the railway lines as fl at as possible so that passengers also from the Middle East, Africa, Asia, and North and South could enjoy a pleasant journey while taking in Britain’s won- America. What is normally a one-hour wait can stretch to derful rural scenery. He employed a variety of techniques to two or more hours if you are unfortunate enough to catch a overcome the constraints of the terrain, constructing bridges, busy time of overlapping fl ight arrivals. While this only adds cuttings, and tunnels to achieve this purpose. to the weariness of a long journey, the prospect of comfort Rain, Steam and Speed – The Great Western Railway, a famous awaits you on the other side. -

Walk 3 in Between

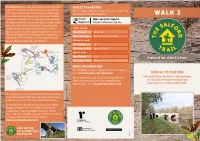

The Salford Trail is a new, long distance walk of about 50 public transport miles/80 kilometres and entirely within the boundaries The new way to find direct bus services to where you of the City of Salford. The route is varied, going through want to go is the Route Explorer. rural areas and green spaces, with a little road walking walk 3 in between. Starting from the cityscape of Salford Quays, tfgm.com/route-explorer the Trail passes beside rivers and canals, through country Access it wherever you are. parks, fields, woods and moss lands. It uses footpaths, tracks and disused railway lines known as ‘loop lines’. Start of walk The Trail circles around to pass through Kersal, Agecroft, Bus Number 92, 93, 95 Walkden, Boothstown and Worsley before heading off to Bus stop location Littleton Road Post Office Chat Moss. The Trail returns to Salford Quays from the historic Barton swing bridge and aqueduct. During the walk Bus Number 484 Blackleach Country Park Bus stop location Agecroft Road 5 3 Clifton Country Park End of walk 4 Walkden Roe Green Bus Number 8, 22 5 miles/8 km, about 2.5 hours Kersal Bus stop location Manchester Road, St Annes’s church 2 Vale 6 Worsley 7 Eccles Chat 1 more information Moss 8 Barton For information on any changes in the route please Swing Salford 9 Bridge Quays go to visitsalford.info/thesalfordtrail kersal to clifton Little Woolden 10 For background on the local history that you will This walk follows the River Irwell upstream Moss as it meanders through woodland and Irlam come across on the trail or for information on wildlife please go to thesalfordtrail.btck.co.uk open spaces to a large country park. -

Manchester M2 6AN Boyle 7 C Brook Emetery Track Telephone 0161 836 6910 - Facsimile 0161 836 6911

Port Salford Project Building Demolitions and Tree Removal Plan Peel Investments (North) Ltd Client Salford CC LPA Date: 28.04.04 Drawing No.: 010022/SLP2 Rev C Scale: 1:10 000 @Application A3 Site Boundary KEY Trees in these areas to be retained. Scattered or occasional trees within these areas to be removed SB 32 Bdy t & Ward Co Cons SL 42 Const Bdy Boro Chat Moss CR 52 Buildings to be Demolished MP 25.25 OAD B 62 ODDINGTON ROA STANNARD R Drain 9 8 72 D 83 43 5 6 GMA PLANNING M 62 36 35 SP 28 35 27 48 3 7 2 0 19 4 0 Drain C HA Drain TLEY ROAD 3 MP 25.25 6 23 King Street, Manchester M2 6AN 12 Planning and Development Consultants Chat Moss 11 CR 32 rd Bdy Wa nst & Co Co Bdy Const e-mail [email protected] o Bor 2 53 8 1 Telephone 0161 836 6910 - Facsimile 0161 836 6911 22 Barton Moss 10 16 ROAD F ETON OXHIL BRER 9 rain 43 D L ROAD 23 Drain 2 0 St Gilbert's 33 Catholic Church MP 25 Presbytery 10 3 2 2 4 Drain Barton Moss 2 Drain Drain CR Drain 1 13 15 Co Const Bdy 6 Track Barton Moss 16 Dra Boro Const and Ward Bdy in MP 24.75 27 Eccles C of E High S Drain FLEET ROAD 6 3 ORTH 26 N SL chool D rain 0 3 Drain 39 Drai n 36 Drain BUC KT HORN D E L OA R Drain AN E D ra ILEY in H M 62 53 44 51 55 Dra 5 9 0 5 in M 62 Drain Brookhouse k Sports Centre Barton Moss Primary School rac T 0 6 63 H ILEY ROA D 6 N 5 O BU RTH D 78 rai 2 CK FLEE n T 67 4 35 H O 3 3 54 RN LA 6 T Pavilion 3 ROAD 75 N 74 E 34 27 25 18 78 6 20 7 80 88 Drain 1 1 TRIPPIER ROAD 6 56 23 58 0 30 6 3 1 n 32 55 89 9 2 7 Drai 6 1 9 6 93 64 3 2 15 95 59 ROCHFORD R 59 2 9 15 66