Journal of Arts & Humanities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal.Uad.Ac.Id/Index.Php/Edulearn J

Journal of Education and Learning (EduLearn) Vol. 13, No. 4, November 2019, pp. 510~517 ISSN: 2089-9823 DOI: 10.11591/edulearn.v13i4.14353 510 Implementation of think-pair-share to mathematics instruction Benidiktus Tanujaya, Jeinne Mumu Department of Mathematics Education, University of Papua, Indonesia Article Info ABSTRACT Article history: The purpose of this research was to study the procedure of think pair share, the type of cooperative learning models, which can be implemented in Received Sep 19, 2019 mathematics instruction in Manokwari, West Papua Indonesia. This study Revised Oct 8, 2019 was conducted at Senior High School in Manokwari (SMA Negeri 1), Accepted Oct 28, 2019 Manokwari West Papua Indonesia. The research was carried out using research and development methods. The Think Pair Share learning model was modified to get the procedure of implementation in accordance with Keywords: the characteristics of students studying mathematics in Manokwari, West Papua. The results of the research showed that there were two Cooperative model principals in the application of the think pair share model in mathematics Mathematics instruction instruction in Manokwari West Papua, selection of group members and the Modification model determination of the number of group members. Students individually start Think-pair-share thinking of finding answers to the assignment submitted. Group members must consist of students who already know each other well, but should not to have a similar level of knowledge, while the number of group members must start from two students. Copyright © 2019 Institute of Advanced Engineering and Science. All rights reserved. Corresponding Author: Jeinne Mumu, Department of Mathematics Education, University of Papua, Manokwari, West Papua, Indonesia. -

Reflections on Linguistic Fieldwork and Language Documentation in Eastern Indonesia

Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 15 Reflections on Language Documentation 20 Years after Himmelmann 1998 ed. by Bradley McDonnell, Andrea L. Berez-Kroeker & Gary Holton, pp. 256–266 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc/ 25 http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24827 Reflections on linguistic fieldwork and language documentation in eastern Indonesia Yusuf Sawaki Center for Endangered Languages Documentation, University of Papua I Wayan Arka Australia National University Udayana University In this paper, we reflect on linguistic fieldwork and language documentation activities in Eastern Indonesia. We first present the rich linguistic and biological diversity of this region, which is of significant interest in typological and theoretical linguistics and language documentation. We then discuss certain central educational issues in relation to human resources, infrastructures, and institutional support, critical for high quality research and documentation. We argue that the issues are multidimensional and complex across all levels, posing sociocultural challenges in capacity-building programs. Finally, we reflect on the significance of the participation oflocal fieldworkers and communities and their contextual training. 1. Introduction In this paper, we reflect on linguistic fieldwork and language documentation in Eastern Indonesia. By “Eastern Indonesia,” we mean the region that stretches from Nusa Tenggara to Papua,1 including Nusa Tenggara Timur, Sulawesi, and Maluku. This region is linguistically one of the most diverse regions in the world interms of the number of unrelated languages and their structural properties, further discussed in the next section. This is the region where Nikolaus Himmelmann has done his linguistic 1The term “Papua” is potentially confusing because it is used in two senses. -

In Antoinette SCHAPPER, Ed., Contact and Substrate in the Languages of Wallacea PART 1

Contact and substrate in the languages of Wallacea: Introduction Antoinette SCHAPPER KITLV & University of Cologne 1. What is Wallacea?1 The term “Wallacea” originally refers to a zoogeographical area located between the ancient continents of Sundaland (the Malay Peninsula, Sumatra, Borneo, Java, and Bali) and Sahul (Australia and New Guinea) (Dickerson 1928). Wallacea includes Sulawesi, Lombok, Sumbawa, Flores, Sumba, Timor, Halmahera, Buru, Seram, and many smaller islands of eastern Indonesia and independent Timor-Leste (Map 1). What characterises this region is its diverse biota drawn from both the Southeast Asian and Australian areas. This volume uses the term Wallacea to refer to a linguistic area (Schapper 2015). In linguistic terms as in biogeography, Wallacea constitutes a transition zone, a region in which we observe the progression attenuation of the Southeast Asian linguistic type to that of a Melanesian linguistic type (Gil 2015). Centred further to the east than Biological Wallacea, Linguistic Wallacea takes in the Papuan and Austronesian languages in the region of eastern Nusantara including the Minor Sundic Islands east of Lombok, Timor-Leste, Maluku, the Bird’s Head and Neck of New Guinea, and Cenderawasih Bay (Map 2). Map 1. Biological Wallacea Map 2. Linguistic Wallacea 1 My editing and research for this issue has been supported by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research VENI project “The evolution of the lexicon. Explorations in lexical stability, semantic shift and borrowing in a Papuan language family” and by the Volkswagen Stiftung DoBeS project “Aru languages documentation”. Many thanks to Asako Shiohara and Yanti for giving me the opportunity to work with them on editing this NUSA special issue. -

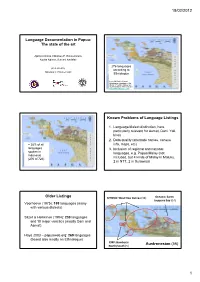

Language Documentation in Papua: the State of the Art

18/02/2012 Language Documentation in Papua: The state of the art Apriani Arilaha, Nikolaus P. Himmelmann, Novita Ndiken, Sutriani Narfafan 276 languages presented by according to Nikolaus P. Himmelmann Ethnologue Lewis, M. Paul (ed.), 2009. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 16th edition. Dallas, Tex.: SIL International. Online version: http://www.ethnologue.com/ Known Problems of Language Listings 1. Language/dialect distinction, here particularly relevant for Asmat, Dani, Yali, Irires 2. Data quality (alternate names, census = 38% of all info, maps, etc) languages 3. Inclusion of regional and national spoken in languages, e.g. Papua Malay (not Indonesia (276 of 726) included, but 4 kinds of Malay in Maluku, 2 in NTT, 2 in Sulawesi) Older Listings SHWNG: West New Guinea (34) Oceanic: Sarmi Jayapura Bay (14) Voorhoeve (1975): 199 languages (many ? with various dialects) Silzer & Heikkinen (1984): 230 languages and 10 major varieties (mostly Dani and Asmat). Hays 2003 – papuaweb.org: 269 languages (based also mostly on Ethnologue) CMP: Bomberai Austronesian (56) North/South (5) 1 18/02/2012 Papuan Languages (220) Speaker numbers Lakes Plain (20) Tor Kwerba (24) Largest, smallest, mean, median Trans‐New Guinea (93) Administrative structure of Irian Jaya before Sociopolitical Setting 1998 (?): 1 Province, 12 Kabupaten Kab. Biak Numfor Accelerating change in the last 150 years: Kab. Manokwari Kab. Sorong Kab. Yapen Waropen - Christian mission since 1855, last ‘first’ Kab. Jayapura Kab. Nabire contacts in the late 1970s Kab. Puncak Jaya Kab. Fakfak Kab. Paniai - Dutch colonial rule 1898 till 1962 Kab. Jayawijaya Kab. Mimika - Indonesiasikan 1962-1998 Kab. Merauke - Otonomi daerah 2001-?? PROVINSI PAPUA Demographic change Population figures 1988/2010 2010 1988 Papua Papua Barat (Irian Jaya) Rural Urban Rural Urban PROVINSI PAPUA BARAT 2.097.752 735.629 532.659 227.763 2.833.381 760.422 Now 2 Provinces with all 1,452,900 3,593,803 together 28 Kabupaten (19 Kabupaten in Papua and 9 Kabupaten in Papua Barat). -

The Position of Enggano Within Austronesian

7KH3RVLWLRQRI(QJJDQRZLWKLQ$XVWURQHVLDQ 2ZHQ(GZDUGV Oceanic Linguistics, Volume 54, Number 1, June 2015, pp. 54-109 (Article) 3XEOLVKHGE\8QLYHUVLW\RI+DZDL L3UHVV For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/ol/summary/v054/54.1.edwards.html Access provided by Australian National University (24 Jul 2015 10:27 GMT) The Position of Enggano within Austronesian Owen Edwards AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Questions have been raised about the precise genetic affiliation of the Enggano language of the Barrier Islands, Sumatra. Such questions have been largely based on Enggano’s lexicon, which shows little trace of an Austronesian heritage. In this paper, I examine a wider range of evidence and show that Enggano is clearly an Austronesian language of the Malayo-Polynesian (MP) subgroup. This is achieved through the establishment of regular sound correspondences between Enggano and Proto‒Malayo-Polynesian reconstructions in both the bound morphology and lexicon. I conclude by examining the possible relations of Enggano within MP and show that there is no good evidence of innovations shared between Enggano and any other MP language or subgroup. In the absence of such shared innovations, Enggano should be considered one of several primary branches of MP. 1. INTRODUCTION.1 Enggano is an Austronesian language spoken on the southernmost of the Barrier Islands off the west coast of the island of Sumatra in Indo- nesia; its location is marked by an arrow on map 1. The genetic position of Enggano has remained controversial and unresolved to this day. Two proposals regarding the genetic classification of Enggano have been made: 1. -

Permissive Residents: West Papuan Refugees Living in Papua New Guinea

Permissive residents West PaPuan refugees living in PaPua neW guinea Permissive residents West PaPuan refugees living in PaPua neW guinea Diana glazebrook MonograPhs in anthroPology series Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/permissive_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Glazebrook, Diana. Title: Permissive residents : West Papuan refugees living in Papua New Guinea / Diana Glazebrook. ISBN: 9781921536229 (pbk.) 9781921536236 (online) Subjects: Ethnology--Papua New Guinea--East Awin. Refugees--Papua New Guinea--East Awin. Refugees--Papua (Indonesia) Dewey Number: 305.8009953 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Teresa Prowse. Printed by University Printing Services, ANU This edition © 2008 ANU E Press Dedicated to the memory of Arnold Ap (1 July 1945 – 26 April 1984) and Marthen Rumabar (d. 2006). Table of Contents List of Illustrations ix Acknowledgements xi Glossary xiii Prologue 1 Intoxicating flag Chapter 1. Speaking historically about West Papua 13 Chapter 2. Culture as the conscious object of performance 31 Chapter 3. A flight path 51 Chapter 4. Sensing displacement 63 Chapter 5. Refugee settlements as social spaces 77 Chapter 6. Inscribing the empty rainforest with our history 85 Chapter 7. Unsated sago appetites 95 Chapter 8. Becoming translokal 107 Chapter 9. Permissive residents 117 Chapter 10. Relocation to connected places 131 Chapter 11. -

Kodrah Kristang: the Initiative to Revitalize the Kristang Language in Singapore

Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 19 Documentation and Maintenance of Contact Languages from South Asia to East Asia ed. by Mário Pinharanda-Nunes & Hugo C. Cardoso, pp.35–121 http:/nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc/sp19 2 http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24906 Kodrah Kristang: The initiative to revitalize the Kristang language in Singapore Kevin Martens Wong National University of Singapore Abstract Kristang is the critically endangered heritage language of the Portuguese-Eurasian community in Singapore and the wider Malayan region, and is spoken by an estimated less than 100 fluent speakers in Singapore. In Singapore, especially, up to 2015, there was almost no known documentation of Kristang, and a declining awareness of its existence, even among the Portuguese-Eurasian community. However, efforts to revitalize Kristang in Singapore under the auspices of the community-based non-profit, multiracial and intergenerational Kodrah Kristang (‘Awaken, Kristang’) initiative since March 2016 appear to have successfully reinvigorated community and public interest in the language; more than 400 individuals, including heritage speakers, children and many people outside the Portuguese-Eurasian community, have joined ongoing free Kodrah Kristang classes, while another 1,400 participated in the inaugural Kristang Language Festival in May 2017, including Singapore’s Deputy Prime Minister and the Portuguese Ambassador to Singapore. Unique features of the initiative include the initiative and its associated Portuguese-Eurasian community being situated in the highly urbanized setting of Singapore, a relatively low reliance on financial support, visible, if cautious positive interest from the Singapore state, a multiracial orientation and set of aims that embrace and move beyond the language’s original community of mainly Portuguese-Eurasian speakers, and, by design, a multiracial youth-led core team. -

Tungusic Languages

641 TUNGUSIC LANGUAGES he last Imperial family that reigned in Beij- Nanai or Goldi has about 7,000 speakers on the T ing, the Qing or Manchu dynasty, seized banks ofthe lower Amur. power in 1644 and were driven out in 1912. Orochen has about 2,000 speakers in northern Manchu was the ancestral language ofthe Qing Manchuria. court and was once a major language ofthe Several other Tungusic languages survive, north-eastern province ofManchuria, bridge- with only a few hundred speakers apiece. head ofthe Japanese invasion ofChina in the 1930s. It belongs to the little-known Tungusic group Numerals in Manchu, Evenki and Nanai oflanguages, usually believed to formpart ofthe Manchu Evenki Nanai ALTAIC family. All Tungusic languages are spo- 1 emu umuÅn emun ken by very small population groups in northern 2 juwe dyuÅr dyuer China and eastern Siberia. 3 ilan ilan ilan Manchu is the only Tungusic language with a 4 duin digin duin written history. In the 17th century the Manchu 5 sunja tungga toinga rulers ofChina, who had at firstruled through 6 ninggun nyungun nyungun the medium of MONGOLIAN, adapted Mongolian 7 nadan nadan nadan script to their own language, drawing some ideas 8 jakon dyapkun dyakpun from the Korean syllabary. However, in the 18th 9 uyun eÅgin khuyun and 19th centuries Chinese ± language ofan 10 juwan dyaÅn dyoan overwhelming majority ± gradually replaced Manchu in all official and literary contexts. From George L. Campbell, Compendium of the world's languages (London: Routledge, 1991) The Tungusic languages Even or Lamut has 7,000 speakers in Sakha, the Kamchatka peninsula and the eastern Siberian The mountain forest coast ofRussia. -

A Comparative Study of Yucatec Maya Sign Languages

Josefina Safar A comparative study of Yucatec Maya Sign Languages A comparative study of Yucatec Maya Sign Languages Maya Yucatec of study A comparative Josefina Safar ISBN 978-91-7911-298-1 Department of Linguistics Doctoral Thesis in Linguistics at Stockholm University, Sweden 2020 A comparative study of Yucatec Maya Sign Languages Josefina Safar Academic dissertation for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics at Stockholm University to be publicly defended on Friday 30 October 2020 at 09.00 in hörsal 11, hus F, Universitetsvägen 10 F, digitally via conference (Zoom), public link at department https://www.ling.su.se/ Abstract In my dissertation, I focus on the documentation and comparison of indigenous sign languages in Yucatán, Mexico. I conducted fieldwork in four Yucatec Maya communities with a high incidence of deafness. Because deaf people born into these villages have never had access to an established sign language, they have developed their own local sign languages to communicate with each other and their hearing relatives. Yucatec Maya Sign Languages (YMSLs) are young languages that have emerged over the past decades. The sign languages in the four communities are historically unrelated, but their shared cultural background and the influence of co-speech gestures used by hearing speakers of Yucatec Maya lead to striking similarities in their lexicon and grammar. At the same time, YMSLs display a high degree of variation related to sociolinguistic factors, such as family membership, age, education or language acquisition from deaf adults. In my dissertation, I argue that we can use the phenomenon of variation in young, micro-community sign languages as a window to find out how linguistic conventions are established and which sociolinguistic variables are relevant for shaping sign language structures. -

Word-Prosodic Systems of Raja Ampat Languages

Word-prosodic systems of Raja Ampat languages PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Universiteit Leiden, op gezag van de Rector Magnificus Dr. D.D. Breimer, hoogleraar in de faculteit der Wiskunde en Natuurwetenschappen en die der Geneeskunde, volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties te verdedigen op woensdag 9 januari 2002 te klokke 15.15 uur door ALBERT CLEMENTINA LUDOVICUS REMIJSEN geboren te Merksem (België) in 1974 Promotiecommissie promotores: Prof. Dr. V.J.J.P. van Heuven Prof. Dr. W.A.L. Stokhof referent: Dr. A.C. Cohn, Cornell University overige leden: Prof. Dr. T.C. Schadeberg Prof. Dr. H. Steinhauer Published by LOT phone: +31 30 253 6006 Trans 10 fax: +31 30 253 6000 3512 JK Utrecht e-mail: [email protected] The Netherlands http://www.let.uu.nl/LOT/ Cover illustration: Part of the village Fafanlap (Misool, Raja Ampat archipelago, Indonesia) in the evening light. Photo by Bert Remijsen (February 2000). ISBN 90-76864-09-8 NUGI 941 Copyright © 2001 by Albert C.L. Remijsen. All rights reserved. This book is dedicated to Lex van der Leeden (1922-2001), with friendship and admiration Table of contents Acknowledgements vii Transcription and abbreviations ix 1 Introduction 1 2 The languages of the Raja Ampat archipelago 5 2.1. About this chapter 5 2.2. Background 6 2.2.1. The Austronesian and the Papuan languages, and their origins 6 2.2.2. The South Halmahera-West New Guinea subgroup of Austronesian 8 2.2.2.1. In general 8 2.2.2.2. Within the South Halmahera-West New Guinea (SHWNG) subgroup 9 2.2.2.3. -

The Language Situation in Vanuatu Terry Crowley Published Online: 26 Mar 2010

This article was downloaded by: [Monterey Inst of International Studies] On: 16 December 2013, At: 22:46 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Current Issues in Language Planning Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rclp20 The Language Situation in Vanuatu Terry Crowley Published online: 26 Mar 2010. To cite this article: Terry Crowley (2000) The Language Situation in Vanuatu, Current Issues in Language Planning, 1:1, 47-132, DOI: 10.1080/14664200008668005 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14664200008668005 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. -

Remijsen Phd (2002) Word-Prosodic Systems of the Raja

Word-prosodic systems of Raja Ampat languages PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Universiteit Leiden, op gezag van de Rector Magnificus Dr. D.D. Breimer, hoogleraar in de faculteit der Wiskunde en Natuurwetenschappen en die der Geneeskunde, volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties te verdedigen op woensdag 9 januari 2002 te klokke 15.15 uur door ALBERT CLEMENTINA LUDOVICUS REMIJSEN geboren te Merksem (België) in 1974 Promotiecommissie promotores: Prof. Dr. V.J.J.P. van Heuven Prof. Dr. W.A.L. Stokhof referent: Dr. A.C. Cohn, Cornell University overige leden: Prof. Dr. T.C. Schadeberg Prof. Dr. H. Steinhauer Published by LOT phone: +31 30 253 6006 Trans 10 fax: +31 30 253 6000 3512 JK Utrecht e-mail: [email protected] The Netherlands http://www.let.uu.nl/LOT/ Cover illustration: Part of the village Fafanlap (Misool, Raja Ampat archipelago, Indonesia) in the evening light. Photo by Bert Remijsen (February 2000). ISBN 90-76864-09-8 NUGI 941 Copyright © 2001 by Albert C.L. Remijsen. All rights reserved. This book is dedicated to Lex van der Leeden (1922-2001), with friendship and admiration Table of contents Acknowledgements vii Transcription and abbreviations ix 1 Introduction 1 2 The languages of the Raja Ampat archipelago 5 2.1. About this chapter 5 2.2. Background 6 2.2.1. The Austronesian and the Papuan languages, and their origins 6 2.2.2. The South Halmahera-West New Guinea subgroup of Austronesian 8 2.2.2.1. In general 8 2.2.2.2. Within the South Halmahera-West New Guinea (SHWNG) subgroup 9 2.2.2.3.