A Comparative Study of Yucatec Maya Sign Languages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

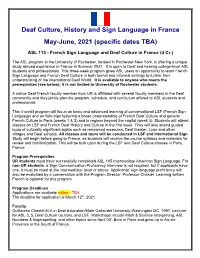

Deaf Culture, History and Sign Language in France May-June, 2021 (Specific Dates TBA)

Deaf Culture, History and Sign Language in France May-June, 2021 (specific dates TBA) ASL 113 - French Sign Language and Deaf Culture in France (4 Cr.) The ASL program at the University of Rochester, located in Rochester New York, is offering a unique study abroad experience in France in Summer 2021. It is open to Deaf and hearing college-level ASL students and professionals. This three-week program gives ASL users an opportunity to learn French Sign Language and French Deaf Culture in both formal and informal settings to further their understanding of the international Deaf World. It is available to anyone who meets the prerequisites (see below); it is not limited to University of Rochester students. A native Deaf French faculty member from UR is affiliated with several faculty members in the Deaf community and they jointly plan the program, schedule, and curriculum offered to ASL students and professionals. This 4-credit program will focus on basic and advanced learning of conversational LSF (French Sign Language) and on field trips fostering a broad understanding of French Deaf Culture and general French Culture in Paris (weeks 1 & 2) and in regions beyond the capital (week 3). Students will attend classes on LSF and French Deaf History and Culture in the first week. They will also attend guided tours of culturally significant sights such as renowned museums, Deaf theater, Lyon and other villages and Deaf schools. All classes and tours will be conducted in LSF and International Sign. Study will begin before going to France, as students will receive the course syllabus and materials for review and familiarization. -

Sign Language Typology Series

SIGN LANGUAGE TYPOLOGY SERIES The Sign Language Typology Series is dedicated to the comparative study of sign languages around the world. Individual or collective works that systematically explore typological variation across sign languages are the focus of this series, with particular emphasis on undocumented, underdescribed and endangered sign languages. The scope of the series primarily includes cross-linguistic studies of grammatical domains across a larger or smaller sample of sign languages, but also encompasses the study of individual sign languages from a typological perspective and comparison between signed and spoken languages in terms of language modality, as well as theoretical and methodological contributions to sign language typology. Interrogative and Negative Constructions in Sign Languages Edited by Ulrike Zeshan Sign Language Typology Series No. 1 / Interrogative and negative constructions in sign languages / Ulrike Zeshan (ed.) / Nijmegen: Ishara Press 2006. ISBN-10: 90-8656-001-6 ISBN-13: 978-90-8656-001-1 © Ishara Press Stichting DEF Wundtlaan 1 6525XD Nijmegen The Netherlands Fax: +31-24-3521213 email: [email protected] http://ishara.def-intl.org Cover design: Sibaji Panda Printed in the Netherlands First published 2006 Catalogue copy of this book available at Depot van Nederlandse Publicaties, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Den Haag (www.kb.nl/depot) To the deaf pioneers in developing countries who have inspired all my work Contents Preface........................................................................................................10 -

A Lexicostatistic Survey of the Signed Languages in Nepal

DigitalResources Electronic Survey Report 2012-021 ® A Lexicostatistic Survey of the Signed Languages in Nepal Hope M. Hurlbut A Lexicostatistic Survey of the Signed Languages in Nepal Hope M. Hurlbut SIL International ® 2012 SIL Electronic Survey Report 2012-021, June 2012 © 2012 Hope M. Hurlbut and SIL International ® All rights reserved 2 Contents 0. Introduction 1.0 The Deaf 1.1 The deaf of Nepal 1.2 Deaf associations 1.3 History of deaf education in Nepal 1.4 Outside influences on Nepali Sign Language 2.0 The Purpose of the Survey 3.0 Research Questions 4.0 Approach 5.0 The survey trip 5.1 Kathmandu 5.2 Surkhet 5.3 Jumla 5.4 Pokhara 5.5 Ghandruk 5.6 Dharan 5.7 Rajbiraj 6.0 Methodology 7.0 Analysis and results 7.1 Analysis of the wordlists 7.2 Interpretation criteria 7.2.1 Results of the survey 7.2.2 Village signed languages 8.0 Conclusion Appendix Sample of Nepali Sign Language Wordlist (Pages 1–6) References 3 Abstract This report concerns a 2006 lexicostatistical survey of the signed languages of Nepal. Wordlists and stories were collected in several towns of Nepal from Deaf school leavers who were considered to be representative of the Nepali Deaf. In each city or town there was a school for the Deaf either run by the government or run by one of the Deaf Associations. The wordlists were transcribed by hand using the SignWriting orthography. Two other places were visited where it was learned that there were possibly unique sign languages, in Jumla District, and also in Ghandruk (a village in Kaski District). -

Sign Language Endangerment and Linguistic Diversity Ben Braithwaite

RESEARCH REPORT Sign language endangerment and linguistic diversity Ben Braithwaite University of the West Indies at St. Augustine It has become increasingly clear that current threats to global linguistic diversity are not re - stricted to the loss of spoken languages. Signed languages are vulnerable to familiar patterns of language shift and the global spread of a few influential languages. But the ecologies of signed languages are also affected by genetics, social attitudes toward deafness, educational and public health policies, and a widespread modality chauvinism that views spoken languages as inherently superior or more desirable. This research report reviews what is known about sign language vi - tality and endangerment globally, and considers the responses from communities, governments, and linguists. It is striking how little attention has been paid to sign language vitality, endangerment, and re - vitalization, even as research on signed languages has occupied an increasingly prominent posi - tion in linguistic theory. It is time for linguists from a broader range of backgrounds to consider the causes, consequences, and appropriate responses to current threats to sign language diversity. In doing so, we must articulate more clearly the value of this diversity to the field of linguistics and the responsibilities the field has toward preserving it.* Keywords : language endangerment, language vitality, language documentation, signed languages 1. Introduction. Concerns about sign language endangerment are not new. Almost immediately after the invention of film, the US National Association of the Deaf began producing films to capture American Sign Language (ASL), motivated by a fear within the deaf community that their language was endangered (Schuchman 2004). -

Anastasia Bauer the Use of Signing Space in a Shared Signing Language of Australia Sign Language Typology 5

Anastasia Bauer The Use of Signing Space in a Shared Signing Language of Australia Sign Language Typology 5 Editors Marie Coppola Onno Crasborn Ulrike Zeshan Editorial board Sam Lutalo-Kiingi Irit Meir Ronice Müller de Quadros Roland Pfau Adam Schembri Gladys Tang Erin Wilkinson Jun Hui Yang De Gruyter Mouton · Ishara Press The Use of Signing Space in a Shared Sign Language of Australia by Anastasia Bauer De Gruyter Mouton · Ishara Press ISBN 978-1-61451-733-7 e-ISBN 978-1-61451-547-0 ISSN 2192-5186 e-ISSN 2192-5194 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. ” 2014 Walter de Gruyter, Inc., Boston/Berlin and Ishara Press, Lancaster, United Kingdom Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck Țȍ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Acknowledgements This book is the revised and edited version of my doctoral dissertation that I defended at the Faculty of Arts and Humanities of the University of Cologne, Germany in January 2013. It is the result of many experiences I have encoun- tered from dozens of remarkable individuals who I wish to acknowledge. First of all, this study would have been simply impossible without its partici- pants. The data that form the basis of this book I owe entirely to my Yolngu family who taught me with patience and care about this wonderful Yolngu language. -

Assessing the Bimodal Bilingual Language Skills of Young Deaf Children

ANZCED/APCD Conference CHRISTCHURCH, NZ 7-10 July 2016 Assessing the bimodal bilingual language skills of young deaf children Elizabeth Levesque PhD What we’ll talk about today Bilingual First Language Acquisition Bimodal bilingualism Bimodal bilingual assessment Measuring parental input Assessment tools Bilingual First Language Acquisition Bilingual literature generally refers to children’s acquisition of two languages as simultaneous or sequential bilingualism (McLaughlin, 1978) Simultaneous: occurring when a child is exposed to both languages within the first three years of life (not be confused with simultaneous communication: speaking and signing at the same time) Sequential: occurs when the second language is acquired after the child’s first three years of life Routes to bilingualism for young children One parent-one language Mixed language use by each person One language used at home, the other at school Designated times, e.g. signing at bath and bed time Language mixing, blending (Lanza, 1992; Vihman & McLaughlin, 1982) Bimodal bilingualism Refers to the use of two language modalities: Vocal: speech Visual-gestural: sign, gesture, non-manual features (Emmorey, Borinstein, & Thompson, 2005) Equal proficiency in both languages across a range of contexts is uncommon Balanced bilingualism: attainment of reasonable competence in both languages to support effective communication with a range of interlocutors (Genesee & Nicoladis, 2006; Grosjean, 2008; Hakuta, 1990) Dispelling the myths….. Infants’ first signs are acquired earlier than first words No significant difference in the emergence of first signs and words - developmental milestones are met within similar timeframes (Johnston & Schembri, 2007) Slight sign language advantage at the one-word stage, perhaps due to features being more visible and contrastive than speech (Meier & Newport,1990) Another myth…. -

Alignment Mouth Demonstrations in Sign Languages Donna Jo Napoli

Mouth corners in sign languages Alignment mouth demonstrations in sign languages Donna Jo Napoli, Swarthmore College, [email protected] Corresponding Author Ronice Quadros, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, [email protected] Christian Rathmann, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, [email protected] 1 Mouth corners in sign languages Alignment mouth demonstrations in sign languages Abstract: Non-manual articulations in sign languages range from being semantically impoverished to semantically rich, and from being independent of manual articulations to coordinated with them. But, while this range has been well noted, certain non-manuals remain understudied. Of particular interest to us are non-manual articulations coordinated with manual articulations, which, when considered in conjunction with those manual articulations, are semantically rich. In which ways can such different articulators coordinate and what is the linguistic effect or purpose of such coordination? Of the non-manual articulators, the mouth is articulatorily the most versatile. We therefore examined mouth articulations in a single narrative told in the sign languages of America, Brazil, and Germany. We observed optional articulations of the corners of the lips that align with manual articulations spatially and temporally in classifier constructions. The lips, thus, enhance the message by giving redundant information, which should be particularly useful in narratives for children. Examination of a single children’s narrative told in these same three sign languages plus six other sign languages yielded examples of one type of these optional alignment articulations, confirming our expectations. Our findings are coherent with linguistic findings regarding phonological enhancement and overspecification. Keywords: sign languages, non-manual articulation, mouth articulation, hand-mouth coordination 2 Mouth corners in sign languages Alignment mouth demonstration articulations in sign languages 1. -

What Sign Language Creation Teaches Us About Language Diane Brentari1∗ and Marie Coppola2,3

Focus Article What sign language creation teaches us about language Diane Brentari1∗ and Marie Coppola2,3 How do languages emerge? What are the necessary ingredients and circumstances that permit new languages to form? Various researchers within the disciplines of primatology, anthropology, psychology, and linguistics have offered different answers to this question depending on their perspective. Language acquisition, language evolution, primate communication, and the study of spoken varieties of pidgin and creoles address these issues, but in this article we describe a relatively new and important area that contributes to our understanding of language creation and emergence. Three types of communication systems that use the hands and body to communicate will be the focus of this article: gesture, homesign systems, and sign languages. The focus of this article is to explain why mapping the path from gesture to homesign to sign language has become an important research topic for understanding language emergence, not only for the field of sign languages, but also for language in general. © 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. How to cite this article: WIREs Cogn Sci 2012. doi: 10.1002/wcs.1212 INTRODUCTION linguistic community, a language model, and a 21st century mind/brain that well-equip the child for this esearchers in a variety of disciplines offer task. When the very first languages were created different, mostly partial, answers to the question, R the social and physiological conditions were very ‘What are the stages of language creation?’ Language different. Spoken language pidgin varieties can also creation can refer to any number of phylogenic and shed some light on the question of language creation. -

The Position of Enggano Within Austronesian

7KH3RVLWLRQRI(QJJDQRZLWKLQ$XVWURQHVLDQ 2ZHQ(GZDUGV Oceanic Linguistics, Volume 54, Number 1, June 2015, pp. 54-109 (Article) 3XEOLVKHGE\8QLYHUVLW\RI+DZDL L3UHVV For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/ol/summary/v054/54.1.edwards.html Access provided by Australian National University (24 Jul 2015 10:27 GMT) The Position of Enggano within Austronesian Owen Edwards AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Questions have been raised about the precise genetic affiliation of the Enggano language of the Barrier Islands, Sumatra. Such questions have been largely based on Enggano’s lexicon, which shows little trace of an Austronesian heritage. In this paper, I examine a wider range of evidence and show that Enggano is clearly an Austronesian language of the Malayo-Polynesian (MP) subgroup. This is achieved through the establishment of regular sound correspondences between Enggano and Proto‒Malayo-Polynesian reconstructions in both the bound morphology and lexicon. I conclude by examining the possible relations of Enggano within MP and show that there is no good evidence of innovations shared between Enggano and any other MP language or subgroup. In the absence of such shared innovations, Enggano should be considered one of several primary branches of MP. 1. INTRODUCTION.1 Enggano is an Austronesian language spoken on the southernmost of the Barrier Islands off the west coast of the island of Sumatra in Indo- nesia; its location is marked by an arrow on map 1. The genetic position of Enggano has remained controversial and unresolved to this day. Two proposals regarding the genetic classification of Enggano have been made: 1. -

AN ETHNOGRAPHY of DEAF PEOPLE in TANZANIA By

THEY HAVE TO SEE US: AN ETHNOGRAPHY OF DEAF PEOPLE IN TANZANIA by Jessica C. Lee B.A., University of Northern Colorado, 2001 M.A., Gallaudet University, 2004 M.A., University of Colorado, 2006 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the degree requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology 2012 ii This thesis entitled: They Have To See Us: an Ethnography of Deaf People in Tanzania written by Jessica Chantelle Lee has been approved for the Department of Anthropology J. Terrence McCabe Dennis McGilvray Paul Shankman --------------------------------------------- Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. IRB protocol # 13090619 iii ABSTRACT They Have To See Us: an Ethnography of Deaf People in Tanzania Jessica Lee Department of Anthropology Thesis directed by Professor J. Terrence McCabe This dissertation explores the relationship between Tanzanian deaf people and mainstream society, as well as dynamics within deaf communities. I argue that deaf people who do participate in NGOs and other organizations that provide support to deaf people, do so strategically. In order to access services and improve their own lives and the lives of their families, deaf people in Tanzania move comfortably and fluidly between identity groups that are labeled as disabled or only as deaf. Through intentional use of the interventions provided by various organizations, deaf people are able to carve out deaf spaces that act as places for transmission of information, safe areas to learn and use sign language, and sites of network and community development among other deaf people. -

Iconicity As a Pervasive Force in Language: Evidence from Ghanaian Sign

Iconicity as a pervasive force in language: Evidence from Ghanaian Sign Language and Adamorobe Sign Language By Mary Edward A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Brighton for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Humanities University of Brighton 2021 Abstract In this dissertation, I investigate various manifestations of iconicity and how these are demonstrated in the visual-spatial modality, focusing specifically on Ghanaian Sign Language (GSL) and Adamorobe Sign Language (AdaSL). The dissertation conducts three main empirical analyses comparing GSL and AdaSL. The data for the analyses were elicited from deaf participants using lexical elicitation and narrative tasks. The first study considers iconicity in GSL and AdaSL lexical items. This study additionally compares the iconic strategies used by signers to those produced in gestures by hearing non-signers in the surrounding communities. The second study investigates iconicity in the spatial domain, focusing on the iconic use of space to depict location, motion, action. The third study looks specifically at the use of, simultaneous constructions, and compares the use of different types of simultaneous constructions between the two sign languages. Finally, the dissertation offers a theoretical analysis of the data across the studies from a cognitive linguistics perspective on iconicity in language. The study on lexical iconicity compares GSL and AdaSL signers’ use of iconic strategies across five semantic categories: Handheld tools, Clothing & Accessories, Furniture & Household items, Appliances, and Nature. Findings are discussed with respect to patterns of iconicity across semantic categories, and with respect to similarities and differences between signs and gestures. -

Code-Blending with Depicting Signs

Code-blending with Depicting Signs Code-blending with Depicting Signs Ronice Quadros1, Kathryn Davidson2, Diane Lillo-Martin3, and Karen Emmorey4 1Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina/2Harvard University/3University of Connecticut/4San Diego State University Abstract Bimodal bilinguals sometimes use code-blending, simultaneous production of (parts of) an utterance in both speech and sign. We ask what spoken language material is blended with entity and handling depicting signs (DS), representations of action that combine discrete components with iconic depictions of aspects of a referenced event in a gradient, analog manner. We test a semantic approach that DS may involve a demonstration, involving a predicate which selects for an iconic demonstrational argument, and adopt a syntactic analysis which crucially distinguishes between entity and handling DS. Given this analysis and our model of bilingualism, we expect DS to be blended with restricted structures: either iconic vocal gestures/demonstrations or with spoken language predicates. Further we predict that handling, but not entity, DS may occur in blends with subjects. Data from three hearing native bimodal bilinguals from the United States and one from Brazil support these predictions. Keywords: bimodal bilingualism; code-blending; depicting signs; demonstration; semantics 1 Code-blending with Depicting Signs Code-blending with Depicting Signs 1. Introduction In this squib, we analyze production data from hearing bimodal bilinguals – adults whose native languages include a sign language and a spoken language. Bimodal bilinguals engage in a bilingual phenomenon akin to code-switching, but unique to the bimodal situation: code-blending (Emmorey, Giezen, & Gollan, 2016). In code-blending, aspects of a spoken and signed utterance are produced simultaneously; this is possible since the articulators of speech and sign are largely separate.