The Austronesian Languages of Asia and Madagascar Colonial History and Language Policy in Insular Southeast Asia and Madagascar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Fi~Eeting Encounter with the Moken Cthe Sea Gypsies) in Southern Thailand: Some Linguistic and General Notes

A FI~EETING ENCOUNTER WITH THE MOKEN CTHE SEA GYPSIES) IN SOUTHERN THAILAND: SOME LINGUISTIC AND GENERAL NOTES by Christopher Court During a short trip (3-5 April 1970) to the islands of King Amphoe Khuraburi (formerly Koh Kho Khao) in Phang-nga Province in Southern Thailand, my curiosity was aroused by frequent references in conversation with local inhabitants to a group of very primitive people (they were likened to the Spirits of the Yellow Leaves) whose entire life was spent nomadically on small boats. It was obvious that this must be the Moken described by White ( 1922) and Bernatzik (1939, and Bernatzik and Bernatzik 1958: 13-60). By a stroke of good fortune a boat belonging to this group happened to come into the beach at Ban Pak Chok on the island of Koh Phrah Thong, where I was spending the afternoon. When I went to inspect the craft and its occupants it turned out that there were only women and children on board, the one man among the occupants having gone ashore on some errand. The women were extremely shy. Because of this, and the failing light, and the fact that I was short of film, I took only two photographs, and then left the people in peace. Later, when the man returned, I interviewed him briefly elsewhere (see f. n. 2) collecting a few items of vocabulary. From this interview and from conversations with the local residents, particularly Mr. Prapa Inphanthang, a trader who has many dealings with the Moken, I pieced together something of the life and language of these people. -

Tagalog Author: Valeria Malabonga

Heritage Voices: Language - Tagalog Author: Valeria Malabonga About the Tagalog Language Tagalog is a language spoken in the central part of the Philippines and belongs to the Malayo-Polynesian language family. Tagalog is one of the major languages in the Philippines. The standardized form of Tagalog is called Filipino. Filipino is the national language of the Philippines. Filipino and English are the two official languages of the Philippines (Malabonga & Marinova-Todd, 2007). Within the Philippines, Tagalog is spoken in Manila, most of central Luzon, and Palawan. Tagalog is also spoken by persons of Filipino descent in Canada, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom, and the United States. In the United States, large numbers of Filipino immigrants live in California, Hawaii, Illinois, New Jersey, New York, Texas, and Washington (Camarota & McArdle, 2003). According to the 2000 US Census, Tagalog is the sixth most spoken language in the United States, spoken by over a million speakers. There are about 90 million speakers of Tagalog worldwide. Bessie Carmichael Elementary School/Filipino Education Center in San Francisco, California is the only elementary school in the United States that has an English-Tagalog bilingual program (Guballa, 2002). Tagalog is also taught at two high schools in California. It is taught as a subject at James Logan High School, in the New Haven Unified School District (NHUSD) in the San Francisco Bay area (Dizon, 2008) and as an elective at Southwest High School in the Sweetwater Union High School District of San Diego. At the community college level, Tagalog is taught as a second or foreign language at Kapiolani Community College, Honolulu Community College, and Leeward Community College in Hawaii and Sacramento City College in California. -

Language Specific Peculiarities Document for Tagalog As Spoken In

Language specific peculiarities Document for Tagalog as Spoken in the Philippines 1. Dialects Tagalog is spoken by around 25 million1 people as a first language and approximately 60 million as a second language. It is the local language spoken by most Filipinos and serves as a lingua franca in most parts of the Philippines. It is also the de facto national language of the Philippines together with English. Although officially the name of the national language is "Filipino", which has Tagalog as its basis, the majority of Filipinos are unaccustomed, even unaware, of this naming convention. Practically speaking, the name "Tagalog" is used by many Filipinos when referring to the national language. "Filipino", on the other hand, is rather ambiguous and, it must be said, carries nationalistic overtones2. The population of Tagalog native speakers is primarily concentrated in a region that covers southern Luzon and nearby islands. In this project, three major dialectal regions of Tagalog will be presented: Dialectal Region Description North Includes the Tagalog spoken in Bulacan, Bataan, Nueva Ecija and parts of Zambales. Central The Tagalog spoken in Manila, parts of Rizal and Laguna. This is the Tagalog dialect that is understood by the majority of the population. South Characteristic of the Tagalog spoken in Batangas, parts of Cavite, major parts of Quezon province and the coastal regions of the island of Mindoro. 1.1. English Influence The standard Tagalog spoken in Manila, the capital of the Philippines, is also considered the prestige dialect of Tagalog. It is the Tagalog used in the media and is taught in schools. -

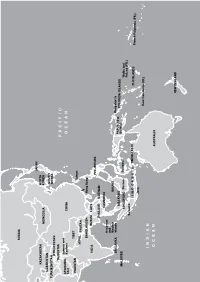

J. Collins Malay Dialect Research in Malysia: the Issue of Perspective

J. Collins Malay dialect research in Malysia: The issue of perspective In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 145 (1989), no: 2/3, Leiden, 235-264 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/28/2021 12:15:07AM via free access JAMES T. COLLINS MALAY DIALECT RESEARCH IN MALAYSIA: THE ISSUE OF PERSPECTIVE1 Introduction When European travellers and adventurers began to explore the coasts and islands of Southeast Asia almost five hundred years ago, they found Malay spoken in many of the ports and entrepots of the region. Indeed, today Malay remains an important indigenous language in Malaysia, Indonesia, Brunei, Thailand and Singapore.2 It should not be a surprise, then, that such a widespread and ancient language is characterized by a wealth of diverse 1 Earlier versions of this paper were presented to the English Department of the National University of Singapore (July 22,1987) and to the Persatuan Linguistik Malaysia (July 23, 1987). I would like to thank those who attended those presentations and provided valuable insights that have contributed to improving the paper. I am especially grateful to Dr. Anne Pakir of Singapore and to Dr. Nik Safiah Karim of Malaysia, who invited me to present a paper. I am also grateful to Dr. Azhar M. Simin and En. Awang Sariyan, who considerably enlivened the presentation in Kuala Lumpur. Professor George Grace and Professor Albert Schiitz read earlier drafts of this paper. I thank them for their advice and encouragement. 2 Writing in 1881, Maxwell (1907:2) observed that: 'Malay is the language not of a nation, but of tribes and communities widely scattered in the East.. -

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

ROGER D. WOODARD, Ed. the Ancient Languages of Asia and the Americas

ROGER D. WOODARD, Ed. The ancient languages of Asia and the Americas. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008. Pp. xix, 264. This is one of five volumes derived from the Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World’s Ancient Languages (2006), from the same editor and publisher. The ten chapters, prepared by noted specialists, are supplemented by 24 figures, 16 tables, and a map. The contents are indexed separately for subject, grammatical and linguistic terms, languages, and establish laws and principles referred to in the text, e.g., Bartholomae’s Law, Grassmann’s Law. The first appendix (234 – 250) provides a comprehensive discussion of methods and problems for reconstructing ancient languages, focusing on the comparative method, while discussing questions of morphology and syntax as well, in the context of Indo-European reconstruction. This is understandable, if not ideal; after all, Indo European languages, despite the rapid advances in East Asian linguistics and especially in more recent work on Austronesian languages, the languages that make up the Indo-European taxa remain the most studied and best understood of the world’s languages. The second reproduces the TOC of the Encyclopedia and the other volumes in this series. We certainly agree with the remark in the Preface, “An ancient language is indeed a thing of wonder — but so is every other language” (1). Since the capacity for language is the faculty that distinguishes the category human, the breadth and scope of the diversity of manifestations of that faculty, along with the means to record it and extend it in space and through time, count as the supreme wonders of existence. -

The Position of Enggano Within Austronesian

7KH3RVLWLRQRI(QJJDQRZLWKLQ$XVWURQHVLDQ 2ZHQ(GZDUGV Oceanic Linguistics, Volume 54, Number 1, June 2015, pp. 54-109 (Article) 3XEOLVKHGE\8QLYHUVLW\RI+DZDL L3UHVV For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/ol/summary/v054/54.1.edwards.html Access provided by Australian National University (24 Jul 2015 10:27 GMT) The Position of Enggano within Austronesian Owen Edwards AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Questions have been raised about the precise genetic affiliation of the Enggano language of the Barrier Islands, Sumatra. Such questions have been largely based on Enggano’s lexicon, which shows little trace of an Austronesian heritage. In this paper, I examine a wider range of evidence and show that Enggano is clearly an Austronesian language of the Malayo-Polynesian (MP) subgroup. This is achieved through the establishment of regular sound correspondences between Enggano and Proto‒Malayo-Polynesian reconstructions in both the bound morphology and lexicon. I conclude by examining the possible relations of Enggano within MP and show that there is no good evidence of innovations shared between Enggano and any other MP language or subgroup. In the absence of such shared innovations, Enggano should be considered one of several primary branches of MP. 1. INTRODUCTION.1 Enggano is an Austronesian language spoken on the southernmost of the Barrier Islands off the west coast of the island of Sumatra in Indo- nesia; its location is marked by an arrow on map 1. The genetic position of Enggano has remained controversial and unresolved to this day. Two proposals regarding the genetic classification of Enggano have been made: 1. -

Learn Thai Language in Malaysia

Learn thai language in malaysia Continue Learning in Japan - Shinjuku Japan Language Research Institute in Japan Briefing Workshop is back. This time we are with Shinjuku of the Japanese Language Institute (SNG) to give a briefing for our students, on learning Japanese in Japan.You will not only learn the language, but you will ... Or nearby, the Thailand- Malaysia border. Almost one million Thai Muslims live in this subregion, which is a belief, and learn how, to grow other (besides rice) crops for which there is a good market; Thai, this term literally means visitor, ASEAN identity, are we there yet? Poll by Thai Tertiary Students ' Sociolinguistic. Views on the ASEAN community. Nussara Waddsorn. The Assumption University usually introduces and offers as a mandatory optional or free optional foreign language course in the state-higher Japanese, German, Spanish and Thai languages of Malaysia. In what part students find it easy or difficult to learn, taking Mandarin READING HABITS AND ATTITUDES OF THAI L2 STUDENTS from MICHAEL JOHN STRAUSS, presented partly to meet the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS (TESOL) I was able to learn Thai with Sukothai, where you can learn a lot about the deep history of Thailand and culture. Be sure to read the guide and learn a little about the story before you go. Also consider visiting neighboring countries like Cambodia, Vietnam and Malaysia. Air LANGUAGE: Thai, English, Bangkok TYPE OF GOVERNMENT: Constitutional Monarchy CURRENCY: Bath (THB) TIME ZONE: GMT No 7 Thailand invites you to escape into a world of exotic enchantment and excitement, from the Malaysian peninsula. -

Asia and Oceania Nicole Girard, Irwin Loy, Marusca Perazzi, Jacqui Zalcberg the Country

ARCTIC OCEAN RUSSIA JAPAN KAZAKHSTAN NORTH MONGOLIA KOREA UZBEKISTAN SOUTH TURKMENISTAN KOREA KYRGYZSTAN TAJIKISTAN PACIFIC Jammu and AFGHANIS- Kashmir CHINA TAN OCEAN PAKISTAN TIBET Taiwan NEPAL BHUTAN BANGLADESH Hong Kong INDIA BURMA LAOS PHILIPPINES THAILAND VIETNAM CAMBODIA Andaman and Nicobar BRUNEI SRI LANKA Islands Bougainville MALAYSIA PAPUA NEW SOLOMON ISLANDS MALDIVES GUINEA SINGAPORE Borneo Sulawesi Wallis and Futuna (FR.) Sumatra INDONESIA TIMOR-LESTE FIJI ISLANDS French Polynesia (FR.) Java New Caledonia (FR.) INDIAN OCEAN AUSTRALIA NEW ZEALAND Asia and Oceania Nicole Girard, Irwin Loy, Marusca Perazzi, Jacqui Zalcberg the country. However, this doctrine is opposed by nationalist groups, who interpret it as an attack on ethnic Kazakh identity, language and Central culture. Language policy is part of this debate. The Asia government has a long-term strategy to gradually increase the use of Kazakh language at the expense Matthew Naumann of Russian, the other official language, particularly in public settings. While use of Kazakh is steadily entral Asia was more peaceful in 2011, increasing in the public sector, Russian is still with no repeats of the large-scale widely used by Russians, other ethnic minorities C violence that occurred in Kyrgyzstan and many urban Kazakhs. Ninety-four per cent during the previous year. Nevertheless, minor- of the population speak Russian, while only 64 ity groups in the region continue to face various per cent speak Kazakh. In September, the Chair forms of discrimination. In Kazakhstan, new of the Kazakhstan Association of Teachers at laws have been introduced restricting the rights Russian-language Schools reportedly stated in of religious minorities. Kyrgyzstan has seen a a roundtable discussion that now 56 per cent continuation of harassment of ethnic Uzbeks in of schoolchildren study in Kazakh, 33 per cent the south of the country, and pressure over land in Russian, and the rest in smaller minority owned by minority ethnic groups. -

LING 185 the Syntax of Austronesian Languages Preliminary Syllabus

LING 185 The Syntax of Austronesian Languages Preliminary syllabus The goal of this class is to provide an introduction into comparative Austronesian syntax by discussing the most pertinent issues of Austronesian languages that have posed challenge to current syntactic theory and suggesting further readings and topics for discussion. The choice of the Austronesian language family as the focus of this class is not accidental. The Austronesian language family—roughly 1,200 genetically related languages dispersed over an area encompassing Madagascar, Taiwan, Southeast Asia, and islands of the Pacific—is often called the largest language family in the world. But it has been relatively little studied. Sophisticated research on the grammar of Austronesian languages did not really begin until the 1930’s and 1940’s (fueled, in part, by military interest in the Pacific region). Although there was a surge of interest in Austronesian in the 1970’s and—even more dramatically—in the 1990’s, the number of theoretical linguists working on these languages has remained small. Nonetheless, Austronesian languages have a significant contribution to make to linguistic theory, given the number of typologically unusual properties they exhibit (including the less common and poorly understood verb‐first word order, ergativity, and wh‐ agreement). If these languages were as well‐understood as, say, the Romance languages are today, syntactic theory could well be dramatically different. The following list illustrates just some of the intriguing features whose theoretical significance—already evident—will surely deepen when they are investigated from a comparative perspective: • Many Austronesian languages exhibit the uncommon word orders verb‐subject‐object (VSO) or verb‐object‐subject (VOS). -

Computational Linguistics Research on Philippine Languages

Computational Linguistics Research on Philippine Languages Rachel Edita O. ROXAS Allan BORRA Software Technology Department Software Technology Department De La Salle University De La Salle University 2401 Taft Avenue, Manila, Philippines 2401 Taft Avenue, Manila, Philippines [email protected] [email protected] languages spoken in Southern Philippines. But Abstract as of yet, extensive research has already been done on theoretical linguistics and little is This is a paper that describes computational known for computational linguistics. In fact, the linguistic activities on Philippines computational linguistics researches on languages. The Philippines is an archipelago Philippine languages are mainly focused on 1 with vast numbers of islands and numerous Tagalog. There are also notable work done on languages. The tasks of understanding, Ilocano. representing and implementing these Kroeger (1993) showed the importance of the languages require enormous work. An grammatical relations in Tagalog, such as extensive amount of work has been done on subject and object relations, and the understanding at least some of the major insufficiency of a surface phrase structure Philippine languages, but little has been paradigm to represent these relations. This issue done on the computational aspect. Majority was further discussed in the LFG98, which is on of the latter has been on the purpose of the problem of voice and grammatical functions machine translation. in Western Austronesian Languages. Musgrave (1998) introduced the problem certain verbs in 1 Philippine Languages these languages that can head more than one transitive clause type. Foley (1998) and Kroeger Within the 7,200 islands of the Philippine (1998), in particular, discussed about long archipelago, there are about one hundred and debated issues such as nouns in Tagalog that can one (101) languages that are spoken. -

The Endangered Languages in Taiwan

The Endangered Languages in Taiwan Paul Li Academia Sinica Abtract All Formosan languages are endangered and threatened with extinction. The problems of the criteria for being endangered languages and what aspects of language to study are briefly discussed. There are five most endangered Formosan languages: Pazih, Thao, Kanakanavu, Saaroa and Kavalan, each with a few speakers left. An account of the work that has been done on each of these languages is given. Finally there is a brief discussion of what has been done to conserve and revitalize all the endangered languages in Taiwan. 1. Languages in Taiwan: The Past and the Present There are two main types of languages spoken in Taiwan, Austronesian and Chinese. All the aboriginal languages, spoken in the plains or mountain areas, belong to the Austronesian language family. The population of the indigenous peoples (450,000) is very small, only barely 2% of the total population of Taiwan (23,000,000). The rest of the population speaks a variety of Chinese dialects, including Mandarin, Minnan (Taiwanese), and Hakka. Mandarin has been adopted as the official language by the Nationalist Government since 1945, and it has become the predominant language at the expense of all the other languages in Taiwan. Hence these languages, especially the aboriginal, are endangered and threatened with extinction. Despite all the efforts of the new government in the past eight years, it seems hard to turn the tide. When I started to work on Rukai, an Austronesian language in Taiwan, in 1970, it was sound and healthy, as were many other Formosan languages, such as Atayal, Seediq, Bunun, Tsou, Paiwan, and Amis.