The Malayic-Speaking Orang Laut Dialects and Directions for Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evidence from the Orang Asli Jakun Community Living in Tropical Peat Swamp Forest, Pahang, Malaysia Shaleh, Muhammad Adha; Guth, Miriam Karen; Rahman, Syed Ajijur

Local understanding of forest conservation in land use change dynamics evidence from the Orang Asli Jakun Community living in tropical peat swamp forest, Pahang, Malaysia Shaleh, Muhammad Adha; Guth, Miriam Karen; Rahman, Syed Ajijur Published in: International Journal of Environmental Planning and Management Publication date: 2016 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Document license: CC BY Citation for published version (APA): Shaleh, M. A., Guth, M. K., & Rahman, S. A. (2016). Local understanding of forest conservation in land use change dynamics: evidence from the Orang Asli Jakun Community living in tropical peat swamp forest, Pahang, Malaysia. International Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 2(2), 6-14. http://files.aiscience.org/journal/article/html/70150037.html Download date: 28. sep.. 2021 International Journal of Environmental Planning and Management Vol. 2, No. 2, 2016, pp. 6-14 http://www.aiscience.org/journal/ijepm ISSN: 2381-7240 (Print); ISSN: 2381-7259 (Online) Local Understanding of Forest Conservation in Land Use Change Dynamics: Evidence from the Orang Asli Jakun Community Living in Tropical Peat Swamp Forest, Pahang, Malaysia Muhammad Adha Shaleh 1, *, Miriam Karen Guth 2, Syed Ajijur Rahman 3, 4, 5 1Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Kulliyyah of Islamic Revealed Knowledge and Human Sciences, International Islamic University of Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 2Roland Close, Cambridge, Cambridgeshire, United Kingdom 3Department of Food and Resource Economics, Section of Environment and Natural Resources, University of Copenhagen, Frederiksberg, Denmark 4School of Environment, Natural Resources and Geography, Bangor University, Bangor, United Kingdom 5Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), Bogor, West Java, Indonesia Abstract The success of local forest conservation program depends on a critical appreciation of local communities. -

A Fi~Eeting Encounter with the Moken Cthe Sea Gypsies) in Southern Thailand: Some Linguistic and General Notes

A FI~EETING ENCOUNTER WITH THE MOKEN CTHE SEA GYPSIES) IN SOUTHERN THAILAND: SOME LINGUISTIC AND GENERAL NOTES by Christopher Court During a short trip (3-5 April 1970) to the islands of King Amphoe Khuraburi (formerly Koh Kho Khao) in Phang-nga Province in Southern Thailand, my curiosity was aroused by frequent references in conversation with local inhabitants to a group of very primitive people (they were likened to the Spirits of the Yellow Leaves) whose entire life was spent nomadically on small boats. It was obvious that this must be the Moken described by White ( 1922) and Bernatzik (1939, and Bernatzik and Bernatzik 1958: 13-60). By a stroke of good fortune a boat belonging to this group happened to come into the beach at Ban Pak Chok on the island of Koh Phrah Thong, where I was spending the afternoon. When I went to inspect the craft and its occupants it turned out that there were only women and children on board, the one man among the occupants having gone ashore on some errand. The women were extremely shy. Because of this, and the failing light, and the fact that I was short of film, I took only two photographs, and then left the people in peace. Later, when the man returned, I interviewed him briefly elsewhere (see f. n. 2) collecting a few items of vocabulary. From this interview and from conversations with the local residents, particularly Mr. Prapa Inphanthang, a trader who has many dealings with the Moken, I pieced together something of the life and language of these people. -

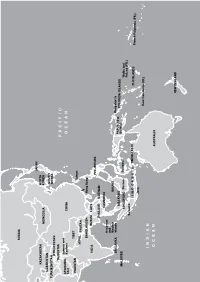

The Linguistic Background to SE Asian Sea Nomadism

The linguistic background to SE Asian sea nomadism Chapter in: Sea nomads of SE Asia past and present. Bérénice Bellina, Roger M. Blench & Jean-Christophe Galipaud eds. Singapore: NUS Press. Roger Blench McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research University of Cambridge Department of History, University of Jos Correspondence to: 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/ Ans (00-44)-(0)1223-560687 Mobile worldwide (00-44)-(0)7847-495590 E-mail [email protected] http://www.rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm This printout: Cambridge, March 21, 2017 Roger Blench Linguistic context of SE Asian sea peoples Submission version TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 3 2. The broad picture 3 3. The Samalic [Bajau] languages 4 4. The Orang Laut languages 5 5. The Andaman Sea languages 6 6. The Vezo hypothesis 9 7. Should we include river nomads? 10 8. Boat-people along the coast of China 10 9. Historical interpretation 11 References 13 TABLES Table 1. Linguistic affiliation of sea nomad populations 3 Table 2. Sailfish in Moklen/Moken 7 Table 3. Big-eye scad in Moklen/Moken 8 Table 4. Lake → ocean in Moklen 8 Table 5. Gill-net in Moklen/Moken 8 Table 6. Hearth on boat in Moklen/Moken 8 Table 7. Fishtrap in Moklen/Moken 8 Table 8. ‘Bracelet’ in Moklen/Moken 8 Table 9. Vezo fish names and their corresponding Malayopolynesian etymologies 9 FIGURES Figure 1. The Samalic languages 5 Figure 2. Schematic model of trade mosaic in the trans-Isthmian region 12 PHOTOS Photo 1. Orang Laut settlement in Riau 5 Photo 2. -

J. Collins Malay Dialect Research in Malysia: the Issue of Perspective

J. Collins Malay dialect research in Malysia: The issue of perspective In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 145 (1989), no: 2/3, Leiden, 235-264 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/28/2021 12:15:07AM via free access JAMES T. COLLINS MALAY DIALECT RESEARCH IN MALAYSIA: THE ISSUE OF PERSPECTIVE1 Introduction When European travellers and adventurers began to explore the coasts and islands of Southeast Asia almost five hundred years ago, they found Malay spoken in many of the ports and entrepots of the region. Indeed, today Malay remains an important indigenous language in Malaysia, Indonesia, Brunei, Thailand and Singapore.2 It should not be a surprise, then, that such a widespread and ancient language is characterized by a wealth of diverse 1 Earlier versions of this paper were presented to the English Department of the National University of Singapore (July 22,1987) and to the Persatuan Linguistik Malaysia (July 23, 1987). I would like to thank those who attended those presentations and provided valuable insights that have contributed to improving the paper. I am especially grateful to Dr. Anne Pakir of Singapore and to Dr. Nik Safiah Karim of Malaysia, who invited me to present a paper. I am also grateful to Dr. Azhar M. Simin and En. Awang Sariyan, who considerably enlivened the presentation in Kuala Lumpur. Professor George Grace and Professor Albert Schiitz read earlier drafts of this paper. I thank them for their advice and encouragement. 2 Writing in 1881, Maxwell (1907:2) observed that: 'Malay is the language not of a nation, but of tribes and communities widely scattered in the East.. -

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

Ancient Genetic Signatures of Orang Asli Revealed by Killer Immunoglobulin-Like Receptor Gene Polymorphisms

RESEARCH ARTICLE Ancient Genetic Signatures of Orang Asli Revealed by Killer Immunoglobulin-Like Receptor Gene Polymorphisms Hanis Z. A. NurWaliyuddin1, Mohd N. Norazmi1,2, Hisham A. Edinur1, Geoffrey K. Chambers3, Sundararajulu Panneerchelvam1, Zainuddin Zafarina1,4* 1 Human Identification/DNA Unit, School of Health Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Health Campus, Kelantan, Malaysia, 2 Institute for Research in Molecular Medicine, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Health Campus, Kelantan, Malaysia, 3 School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand, 4 Malaysian Institute of Pharmaceuticals and Nutraceuticals, National Institutes of Biotechnology Malaysia, Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation, Penang, Malaysia * [email protected] Abstract The aboriginal populations of Peninsular Malaysia, also known as Orang Asli (OA), comprise OPEN ACCESS three major groups; Semang, Senoi and Proto-Malays. Here, we analyzed for the first time Citation: NurWaliyuddin HZA, Norazmi MN, Edinur KIR gene polymorphisms for 167 OA individuals, including those from four smallest OA sub- HA, Chambers GK, Panneerchelvam S, Zafarina Z groups (Che Wong, Orang Kanaq, Lanoh and Kensiu) using polymerase chain reaction- (2015) Ancient Genetic Signatures of Orang Asli sequence specific primer (PCR-SSP) analyses. The observed distribution of KIR profiles of Revealed by Killer Immunoglobulin-Like Receptor OA is heterogenous; Haplotype B is the most frequent in the Semang subgroups (especially Gene Polymorphisms. PLoS ONE 10(11): e0141536. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0141536 Batek) while Haplotype A is the most common type in the Senoi. The Semang subgroups were clustered together with the Africans, Indians, Papuans and Australian Aborigines in a Editor: Niklas K Björkström, Karolinska Institutet, SWEDEN principal component analysis (PCA) plot and shared many common genotypes (AB6, BB71, BB73 and BB159) observed in these other populations. -

Gender, Ethnicity, Infrastructure, and the Use of Financial Institutions in Kalimantan Barat, Indonesia

GENDER, ETHNICITY, INFRASTRUCTURE, AND THE USE OF FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS IN KALIMANTAN BARAT, INDONESIA _______________________________________ A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy _____________________________________________________ by CHRISTINA POMIANEK DAMES Dr. Mary Shenk, Dissertation Supervisor JULY 2012 © Copyright by Christina Dames 2012 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School have examined the dissertation entitled GENDER, ETHNICITY, INFRASTRUCTURE, AND THE USE OF FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS IN KALIMANTAN BARAT, INDONESIA presented by Christina Pomianek Dames, a candidate for the degree of doctor of philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Assistant Professor Mary Shenk Associate Professor Craig Palmer Associate Professor Todd VanPool Professor James S. Rikoon This dissertation is dedicated to the memory of my parents. ACKNOWLEGEMENTS Now at the conclusion of my graduate studies in anthropology, I look back and recognize the many people who have been instrumental in helping me to discover, pursue, and achieve my goals. In thanks. First and foremost, to my dissertation advisor and mentor, Dr. Mary Shenk, for her guidance and for the many hours she has spent reading and commenting on drafts of this dissertation. To my late mentor Dr. Reed Wadley, who is solely responsible for opening my eyes to Indonesia and in Kalimantan Barat. Although we only worked together for a few short years, meeting Dr. Wadley completely changed the course of my life. I am deeply saddened that we are not able to share our ―stories from the field,‖ but I am forever grateful that our paths crossed at all. -

Language Use and Attitudes As Indicators of Subjective Vitality: the Iban of Sarawak, Malaysia

Vol. 15 (2021), pp. 190–218 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24973 Revised Version Received: 1 Dec 2020 Language use and attitudes as indicators of subjective vitality: The Iban of Sarawak, Malaysia Su-Hie Ting Universiti Malaysia Sarawak Andyson Tinggang Universiti Malaysia Sarawak Lilly Metom Universiti Teknologi of MARA The study examined the subjective ethnolinguistic vitality of an Iban community in Sarawak, Malaysia based on their language use and attitudes. A survey of 200 respondents in the Song district was conducted. To determine the objective eth- nolinguistic vitality, a structural analysis was performed on their sociolinguistic backgrounds. The results show the Iban language dominates in family, friend- ship, transactions, religious, employment, and education domains. The language use patterns show functional differentiation into the Iban language as the “low language” and Malay as the “high language”. The respondents have positive at- titudes towards the Iban language. The dimensions of language attitudes that are strongly positive are use of the Iban language, Iban identity, and intergenera- tional transmission of the Iban language. The marginally positive dimensions are instrumental use of the Iban language, social status of Iban speakers, and prestige value of the Iban language. Inferential statistical tests show that language atti- tudes are influenced by education level. However, language attitudes and useof the Iban language are not significantly correlated. By viewing language use and attitudes from the perspective of ethnolinguistic vitality, this study has revealed that a numerically dominant group assumed to be safe from language shift has only medium vitality, based on both objective and subjective evaluation. -

Asia and Oceania Nicole Girard, Irwin Loy, Marusca Perazzi, Jacqui Zalcberg the Country

ARCTIC OCEAN RUSSIA JAPAN KAZAKHSTAN NORTH MONGOLIA KOREA UZBEKISTAN SOUTH TURKMENISTAN KOREA KYRGYZSTAN TAJIKISTAN PACIFIC Jammu and AFGHANIS- Kashmir CHINA TAN OCEAN PAKISTAN TIBET Taiwan NEPAL BHUTAN BANGLADESH Hong Kong INDIA BURMA LAOS PHILIPPINES THAILAND VIETNAM CAMBODIA Andaman and Nicobar BRUNEI SRI LANKA Islands Bougainville MALAYSIA PAPUA NEW SOLOMON ISLANDS MALDIVES GUINEA SINGAPORE Borneo Sulawesi Wallis and Futuna (FR.) Sumatra INDONESIA TIMOR-LESTE FIJI ISLANDS French Polynesia (FR.) Java New Caledonia (FR.) INDIAN OCEAN AUSTRALIA NEW ZEALAND Asia and Oceania Nicole Girard, Irwin Loy, Marusca Perazzi, Jacqui Zalcberg the country. However, this doctrine is opposed by nationalist groups, who interpret it as an attack on ethnic Kazakh identity, language and Central culture. Language policy is part of this debate. The Asia government has a long-term strategy to gradually increase the use of Kazakh language at the expense Matthew Naumann of Russian, the other official language, particularly in public settings. While use of Kazakh is steadily entral Asia was more peaceful in 2011, increasing in the public sector, Russian is still with no repeats of the large-scale widely used by Russians, other ethnic minorities C violence that occurred in Kyrgyzstan and many urban Kazakhs. Ninety-four per cent during the previous year. Nevertheless, minor- of the population speak Russian, while only 64 ity groups in the region continue to face various per cent speak Kazakh. In September, the Chair forms of discrimination. In Kazakhstan, new of the Kazakhstan Association of Teachers at laws have been introduced restricting the rights Russian-language Schools reportedly stated in of religious minorities. Kyrgyzstan has seen a a roundtable discussion that now 56 per cent continuation of harassment of ethnic Uzbeks in of schoolchildren study in Kazakh, 33 per cent the south of the country, and pressure over land in Russian, and the rest in smaller minority owned by minority ethnic groups. -

A Stigmatised Dialect

A SOCIOLINGUISTIC INVESTIGATION OF ACEHNESE WITH A FOCUS ON WEST ACEHNESE: A STIGMATISED DIALECT Zulfadli Bachelor of Education (Syiah Kuala University, Banda Aceh, Indonesia) Master of Arts in Applied Linguistics (University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia) Thesis submitted in total fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Linguistics Faculty of Arts University of Adelaide December 2014 ii iii iv v TABLE OF CONTENTS A SOCIOLINGUISTIC INVESTIGATION OF ACEHNESE WITH A FOCUS ON WEST ACEHNESE: A STIGMATISED DIALECT i TABLE OF CONTENTS v LIST OF FIGURES xi LIST OF TABLES xv ABSTRACT xvii DECLARATION xix ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xxi CHAPTER 1 1 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Preliminary Remarks ........................................................................................... 1 1.2 Acehnese society: Socioeconomic and cultural considerations .......................... 1 1.2.1 Acehnese society .................................................................................. 1 1.2.2 Population and socioeconomic life in Aceh ......................................... 6 1.2.3 Workforce and population in Aceh ...................................................... 7 1.2.4 Social stratification in Aceh ............................................................... 13 1.3 History of Aceh settlement ................................................................................ 16 1.4 Outside linguistic influences on the Acehnese ................................................. 19 1.4.1 The Arabic language.......................................................................... -

Workpapers in Indonesian Languages and Cultures

( J WORKPAPERS IN INDONESIAN LANGUAGES AND CULTURES VOLUME 6 - MALUKU ,. PATTIMURA UNIVERSITY and THE SUMMER INSTITUTE OP LINGUISTICS in cooperation with THE DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION AND CULTURE WORKPAPERS IN INDONESIAN LANGUAGES AND CULTURES VOLUME 6 - MALUKU Nyn D. Laidig, Edi tor PAT'I'IMORA tJlflVERSITY and THE SUMMER IRSTlTUTK OP LIRGOISTICS in cooperation with 'l'BB DBPAR".l'MElI'1' 01' BDUCATIOII ARD CULTURE Workpapers in Indonesian Languages and cultures Volume 6 Maluku Wyn D. Laidig, Editor Printed 1989 Ambon, Maluku, Indonesia Copies of this publication may be obtained from Summer Institute of Linguistics Kotak Pos 51 Ambon, Maluku 97001 Indonesia Microfiche copies of this and other publications of the Summer Institute of Linguistics may be obtained from Academic Book Center Summer Institute of Linguistics 7500 West Camp Wisdom Road l Dallas, TX 75236 U.S.A. ii PRAKATA Dengan mengucap syukur kepada Tuhan yang Masa Esa, kami menyambut dengan gembira penerbitan buku Workpapers in Indonesian Languages , and Cultures. Penerbitan ini menunjukkan adanya suatu kerjasama yang baik antara Universitas Pattimura deng~n Summer Institute of Linguistics; Maluku . Buku ini merupakan wujud nyata peran serta para anggota SIL dalam membantu masyarakat umumnya dan masyarakat pedesaan khususnya Diharapkan dengan terbitnya buku ini akan dapat membantu masyarakat khususnya di pedesaan, dalam meningkatkan pengetahuan dan prestasi mereka sesuai dengan bidang mereka masing-masing. Dengan adanya penerbitan ini, kiranya dapat merangsang munculnya penulis-penulis yang lain yang dapat menyumbangkan pengetahuannya yang berguna bagi kita dan generasi-generasi yang akan datang. Kami ucapkan ' terima kasih kepada para anggota SIL yang telah berupaya sehingga bisa diterbitkannya buku ini Akhir kat a kami ucapkan selamat membaca kepada masyarakat yang mau memiliki buku ini. -

Local Identity, Local Languages, Regional Malay, and the Endangerment of Local Languages in Eastern Indonesia

Local identity, local languages, regional Malay, and the endangerment of local languages in eastern Indonesia John Bowden Jakarta Field Station Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology Malay, like other major ‘world languages’, is in fact a diverse kaleidoscope of different varieties with different influences and varying degrees of mutual intelligibility between so-called ‘dialects’. Varieties of Malay are now national languages in Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia and Brunei, and they are native languages to minority groups in places as diverse as Sri Lanka, the Cocos islands in Australia, the Pattani Malay in southern Thailand, as well as minorities in the south of the Philippines and amongst the Moluccan community in the Netherlands. The national language, Bahasa Indonesia, is a variety of Malay based on the court Malay spoken in Riau sultanate, and it was this variety that served as the basis for the development of the national language after the Indonesian language was selected as the language of Indonesia at the Youth Congress in Bandung prior to independence in 1928. However, alongside official Indonesian, there are also dozens of distinct vernacular ‘Malayic languages’ spoken in Sumatra and Kalimantan, and a large number of lingua franca varieties that have sometimes been spoken for hundreds of years. These varieties are scattered across the Indonesian archipelago, and particularly in the east. Sometimes so- called ‘creole’ varieties of Malay, the eastern dialects, have, over lengthy influence by local languages in their regions, picked up many features that are both characteristic and ‘emblematic’ (see Friedman, 1999) of local languages spoken in their regions. Indonesia is home to more local languages than any country on earth except for its neighbour, Papua New Guinea.