Antonio Damasio, U1 Descartes' Error

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mindfulness in the Life of a Muslim

2 | Mindfulness in the Life of a Muslim Author Biography Justin Parrott has BAs in Physics, English from Otterbein University, MLIS from Kent State University, MRes in Islamic Studies in progress from University of Wales, and is currently Research Librarian for Middle East Studies at NYU in Abu Dhabi. Disclaimer: The views, opinions, findings, and conclusions expressed in these papers and articles are strictly those of the authors. Furthermore, Yaqeen does not endorse any of the personal views of the authors on any platform. Our team is diverse on all fronts, allowing for constant, enriching dialogue that helps us produce high-quality research. Copyright © 2017. Yaqeen Institute for Islamic Research 3 | Mindfulness in the Life of a Muslim Introduction In the name of Allah, the Gracious, the Merciful Modern life involves a daily bustle of noise, distraction, and information overload. Our senses are constantly stimulated from every direction to the point that a simple moment of quiet stillness seems impossible for some of us. This continuous agitation hinders us from getting the most out of each moment, subtracting from the quality of our prayers and our ability to remember Allah. We all know that we need more presence in prayer, more control over our wandering minds and desires. But what exactly can we do achieve this? How can we become more mindful in all aspects of our lives, spiritual and temporal? That is where the practice of exercising mindfulness, in the Islamic context of muraqabah, can help train our minds to become more disciplined and can thereby enhance our regular worship and daily activities. -

Beckett and Nothing Or ‘A Pain in the Stomach’– of a More Fundamental Anxiety Whose Object Is Precisely an Unfathomable and Unbearable Nothingness

11 It’s nothing: Beckett and anxiety Russell Smith On 11 August 1936, Samuel Beckett wrote the following passage – in German – in his notebook: How translucent this mechanism seems to me now, the principle of which is: better to be afraid of something than of nothing. In the fi rst case only a part, in the second the whole is threatened, not to mention the monstrous quality which inseparably belongs to the incomprehensible, one could even say the boundless. [. .] When such an anxiety [Angst] begins to grow a reason [Grund] must quickly be found, as no one has the ability to live with it in its utter absence of reason [Grundlosigkeit]. Thus the neurotic, i.e. Everyman, may declare with great seriousness and in all awe that there is merely a minimal difference between God in heaven and a pain in the stomach. Since both emanate from one source and serve one purpose: to transform anxiety into fear.1 August 1936 was a particularly anxious time for Beckett. He had been living in Dublin for about eight months, since returning from London just before Christmas 1935, having broken off his two-year course of psychoanalysis with Wilfred Bion. As James Knowlson notes, Beckett had presented himself to Bion with ‘severe anxiety symptoms’: ‘a bursting, apparently arrhythmic heart, night sweats, shudders, panic, breathlessness, and, at its most severe, total paralysis’. However, the fact that these symptoms – which fl ared up whenever he stayed with his mother in Dublin – continued to plague him in early 1936 perhaps ‘[led] him to despair that nothing had -

PRESS RELEASE: 21 June 2017 Nica Burns Presents the Sheffield

PRESS RELEASE: 21 June 2017 Nica Burns presents the Sheffield Theatres production of Music by Dan Gillespie Sells Book and Lyrics by Tom MacRae From an idea by Jonathan Butterell Directed by Jonathan Butterell Design by Anna Fleischle Choreography by Kate Prince Lighting design by Lucy Carter Sound design by Paul Groothuis Musical direction by Theo Jamieson Casting by Will Burton Apollo Theatre Previews from Monday 6 November 2017 Press Night Wednesday 22 November 2017 Once upon a time there was a 16-year-old boy who had a secret he wanted to tell... So, he approached a documentary film maker as you do, and asked if they would help him tell it. The resulting documentary was seen by a theatre director and it inspired him to create a musical. A producing regional theatre backed him. He then bumped into a famous musical theatre star who introduced him to a well-known pop composer who was working with a lyricist and book writer. The theatre put on the production. A major producer saw it and offered them a West End theatre. So, thanks to Jamie Campbell, Firecracker Films, Michael Ball, Sheffield Theatres and Nica Burns, a new British musical by a new British theatre writing and directing team, Everybody’s Talking About Jamie opens at the Apollo Theatre on Wednesday 22 November 2017. Fairy tales really do come true. “Touching, Funny, Joyous” THE OBSERVER 1 “Sends you out on a feel-good bubble of happiness” DAILY TELEGRAPH “Everyone should really be talking about Jamie” THE TIMES “The show is terrific and John McCrea gives an exceptional performance. -

Human Nature Must Be Disengaged

THE WELL-SPRINGS OF ACTION: AN ENQUI RV INTO '1-l.M\N NATIJRE' I Richard Broxton Onians' (1951) book, The Opigins of European Thought about the Body, the Mind, the SouZ, the WopZd, Time and Fate, is as exhaustive as the title suggests. Its value rests in enabling us to perceive the dim outlines of a theory of human powers which was present in the minds of the peoples of western Europe before the dawn of history. The phenomenology and osteol ogy with which Onians supplemented the. account, further enable us to locate the physiological processes on which the theory must have been based. It has been lost. Today we possess only fragments. And yet,we repeatedly make recourse to the theory in our behaviours and speech as if we knew its substance. The hand is placed upon the chest when one pledges allegiance to one's country. To indicate assent, one nods one's head. Some one who is over-sexed is called 'horny'. In a Catholic church, one touches one's forehead and one genuflects before the altar. We associate the symbol of a skull and crossbones with death. We ascribe to ourselves the capacity of appreciating the 'aesthetics' of an object, and speak of the inspiration we receive from a speech. These are but 'shreds and patches', but at one point they were connected. The theory rested on a primordial disjunction between fluid and air; between the liquid or liquefiable substances con tained in the brain, the cerebro-spinal column, the genitals and joints, and the breath. -

Negative Emotion in Music: What Is the Attraction? a Qualitative Study

Empirical Musicology Review Vol. 6, No. 4, 2011 Negative Emotion in Music: What is the Attraction? A Qualitative Study SANDRA GARRIDO University of New South Wales EMERY SCHUBERT University of New South Wales ABSTRACT: Why do people listen to music that evokes negative emotions? This paper presents five comparative interviews conducted to examine this question. Individual differences psychology and mood management theory provided a theoretical framework for the investigation which was conducted under a realist paradigm. Data sources were face-to-face interviews of about one hour involving a live music listening experience. Thematic analysis of the data was conducted and both within-case and cross-case analyses were performed. Results confirmed the complexity of variables at play in individual cases while supporting the hypothesis that absorption and dissociation make it possible for the arousal experienced when listening to sad music to be enjoyed without displeasure. At the same time, participants appeared to be seeking a variety of psychological benefits such as reflecting on life-events, enjoying emotional communion, or engaging in a process of catharsis. A novel finding was that maladaptive mood regulation habits may cause some to listen to sad music even when such benefits are not being obtained, supporting some recent empirical evidence on why people are attracted to negative emotion in music. Submitted 2012 February 12; accepted 2012 June 2. KEYWORDS: music, emotion, negative valence, absorption; rumination WHY do we enjoy “a good cry”? It seems counter-intuitive that people would willingly seek out music or other aesthetic experiences that make them cry when we do our best to avoid things that make us cry in “real life” (Vingerhoets et al., 2001). -

Neuropsychodynamic Psychiatry

Neuropsychodynamic Psychiatry Heinz Boeker Peter Hartwich Georg Northoff Editors 123 Neuropsychodynamic Psychiatry Heinz Boeker • Peter Hartwich Georg Northoff Editors Neuropsychodynamic Psychiatry Editors Heinz Boeker Peter Hartwich Psychiatric University Hospital Zurich Hospital of Psychiatry-Psychotherapy- Zurich Psychosomatic Switzerland General Hospital Frankfurt Teaching Hospital of the University Georg Northoff Frankfurt Mind, Brain Imaging, and Neuroethics Germany Institute of Mental Health Research University of Ottawa Ottawa ON, Canada ISBN 978-3-319-75111-5 ISBN 978-3-319-75112-2 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-75112-2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018948668 © Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature 2018 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors, and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

David L.Reed

Curriculum Vitae David L. Reed DAVID L. REED (February 2021) Associate Provost University of Florida EDUCATION AND PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT: Management Development Program, Graduate School of Education, Harvard Univ. 2016 Advanced Leadership for Academic Professionals, University of Florida 2016 Ph.D. Louisiana State University (Biological Sciences) 2000 M.S. Louisiana State University (Zoology) 1994 B.S. University of North Carolina, Wilmington (Biological Sciences) 1991 PROFESSIONAL EXERIENCE: Administrative (University of Florida) Associate Provost, Office of the Provost 2018 –present Associate Director for Research and Collections, Florida Museum 2015 – 2020 Provost Fellow, Office of the Provost 2017 – 2018 Assistant Director for Research and Collections, Florida Museum 2012 – 2015 Academic Curator of Mammals, Florida Museum, University of Florida 2014 – present Associate Curator of Mammals, Florida Museum, University of Florida 2009 – 2014 Assistant Curator of Mammals, Florida Museum, University of Florida 2004 – 2009 Research Assistant Professor, Department of Biology, University of Utah 2003 – 2004 NSF Postdoctoral Fellow, Department of Biology, University of Utah 2001 – 2003 Courtesy/Adjunct Graduate Faculty, Department of Wildlife Ecology and Conservation, UF 2009 – present Graduate Faculty, School of Natural Resources and the Environment, UF 2005 – present Graduate Faculty, Genetics and Genomics Graduate Program, UF 2005 – present Graduate Faculty, Department of Biology, UF 2004 – present ADMINISTRATIVE RECORD: Associate Provost, Office of the Provost, University of Florida July 2018-present Artificial Intelligence • Serve on and organize the AI Executive Workgroup dedicated to highest priority aspects of the AI Initiative. • Organize and host (Emcee) the all-day AI Retreat in April 2020. Had over 600 participants. • Establish AI Workgroups on nearly a dozen topics • Establish and Chair the AI Academic Workgroup focused on the AI Certificate, new and existing AI courses, the development of new certificates, minors, tracks and majors. -

Psychiatry and Neurology

ensic For Ps f yc o h l a o l n o r g u y o J ISSN: 2475-319X Journal of Forensic Psychology Editorial Psychiatry and Neurology Carlos Roberto* Department of Psychology, La Sierra University, California, USA DESCRIPTION between neurological and psychiatric disorders. for instance , it's documented that a lot of patients with paralysis agitans and Psychiatry is that the medicine dedicated to the diagnosis, stroke manifest depression and, in some, dementia. Is there a prevention, and treatment of mental disorders. These include substantive difference between a toxic psychosis (psychiatry) and various maladaptation’s associated with mood, behavior, a metabolic encephalopathy with delirium (neurology) we've cognition, and perceptions. See glossary of psychiatry. known of those examples for several years? Never and dramatic evidence has come largely through functional resonance imaging Neurology is that the branch of drugs concerned with the study and positron emission tomography. Obsessive-compulsive and treatment of disorders of the system nervosum. The system a disorder is characterized by recurrent, unwanted, intrusive ideas, nervosum may be a complex, sophisticated system that regulates images, or impulses that appear silly, weird, nasty, or horrible and coordinates body activities. Its two major divisions: Central nervous system: the brain and medulla spinalis. (obsessions) and by urges to hold out an act (compulsions) which will lessen the discomfort thanks to the obsessions. Increasing the amount of brain serotonin with selective reuptake inhibitors DIFFERENCE BETWEEN PSYCHITARY may control the symptoms and signs of this disorder. Evidence AND NEUROLOGY of a genetic basis in some patients, structural abnormalities of the brain on resonance imaging in others, and abnormal brain For quite 2000 years within the West, neurology and psychiatry function on functional resonance imaging and positron were thought to be a part of one, unified branch of drugs, which emission tomography collectively suggest that schizophrenia may was often designated neuropsychiatry. -

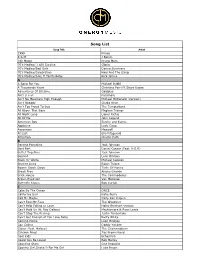

2020 C'nergy Band Song List

Song List Song Title Artist 1999 Prince 6:A.M. J Balvin 24k Magic Bruno Mars 70's Medley/ I Will Survive Gloria 70's Medley/Bad Girls Donna Summers 70's Medley/Celebration Kool And The Gang 70's Medley/Give It To Me Baby Rick James A A Song For You Michael Bublé A Thousands Years Christina Perri Ft Steve Kazee Adventures Of Lifetime Coldplay Ain't It Fun Paramore Ain't No Mountain High Enough Michael McDonald (Version) Ain't Nobody Chaka Khan Ain't Too Proud To Beg The Temptations All About That Bass Meghan Trainor All Night Long Lionel Richie All Of Me John Legend American Boy Estelle and Kanye Applause Lady Gaga Ascension Maxwell At Last Ella Fitzgerald Attention Charlie Puth B Banana Pancakes Jack Johnson Best Part Daniel Caesar (Feat. H.E.R) Bettet Together Jack Johnson Beyond Leon Bridges Black Or White Michael Jackson Blurred Lines Robin Thicke Boogie Oogie Oogie Taste Of Honey Break Free Ariana Grande Brick House The Commodores Brown Eyed Girl Van Morisson Butterfly Kisses Bob Carisle C Cake By The Ocean DNCE California Gurl Katie Perry Call Me Maybe Carly Rae Jespen Can't Feel My Face The Weekend Can't Help Falling In Love Haley Reinhart Version Can't Hold Us (ft. Ray Dalton) Macklemore & Ryan Lewis Can't Stop The Feeling Justin Timberlake Can't Get Enough of You Love Babe Barry White Coming Home Leon Bridges Con Calma Daddy Yankee Closer (feat. Halsey) The Chainsmokers Chicken Fried Zac Brown Band Cool Kids Echosmith Could You Be Loved Bob Marley Counting Stars One Republic Country Girl Shake It For Me Girl Luke Bryan Crazy in Love Beyoncé Crazy Love Van Morisson D Daddy's Angel T Carter Music Dancing In The Street Martha Reeves And The Vandellas Dancing Queen ABBA Danza Kuduro Don Omar Dark Horse Katy Perry Despasito Luis Fonsi Feat. -

Clinical Neurophysiology (CNP) Section Resident Core Curriculum

American Academy of Neurology Clinical Neurophysiology (CNP) Section Resident Core Curriculum 9/7/01 Definition of the Subspecialty of Clinical Neurophysiology The subspecialty of Clinical Neurophysiology involves the assessment of function of the central and peripheral nervous system for the purpose of diagnosing and treatment of neurologic disorders. The CNP procedures commonly used include EEG, EMG, evoked potentials, polysomnography, epilepsy monitoring, intraoperative monitoring, evaluation of movement disorders, and autonomic nervous system testing. The use of CNP procedures requires an understanding of neurophysiology, clinical neurology, and the findings that can occur in various neurologic disorders. The following are the recommended CORE curriculum for residents re CNP. Basic Neurophysiology: Membrane properties of nerve and muscle potentials (resting, action, synaptic, generator), ion channels, synaptic transmission, physiologic basis of EEG, EMG, evoked potentials, sleep mechanisms, autonomic disorders, epilepsy, neuromuscular diseases, and movement disorders Anatomic Substrates of EEG, EMG, evoked potentials, sleep and autonomic activity Indications: Know the indications for and the interpretation of the various CNP tests in the context of the clinical problem. EEG: 1. Recognize normal EEG patterns of infants, children, and adults 2. Recognize abnormal EEG patterns and their clinical significance, including epileptiform patterns, coma patterns, periodic patterns, and the EEG patterns seen with various focal and diffuse neurologic and systemic disorders. 3. Know the EEG criteria for recording in suspected brain death EMG: 1. Know the normal parameters of nerve conduction studies and needle exam of infants, children, and adults 2. Know the abnormal patterns of nerve conduction studies and needle exam and the clinical correlates with various diseases that affect the neuromuscular and peripheral nervous system Evoked Potential Studies 1. -

Behavioral Neurology Fellowship Core Curriculum

AMERICAN ACADEMY OF NEUROLOGY BEHAVIORAL NEUROLOGY FELLOWSHIP CORE CURRICULUM 1. INTRODUCTION AND DEFINITIONS The specialty of Behavioral Neurology focuses on clinical and pathological aspects of neural processes associated with mental activity, subsuming cognitive functions, emotional states, and social behavior. Historically, the principal emphasis of Behavioral Neurology has been to characterize the phenomenology and pathophysiology of intellectual disturbances in relation to brain dysfunction, clinical diagnosis, and treatment. Representative cognitive domains of interest include attention, memory, language, high-order perceptual processing, skilled motor activities, and "frontal" or "executive" cognitive functions (adaptive problem-solving operations, abstract conceptualization, insight, planning, and sequencing, among others). Advances in cognitive neuroscience afforded by functional brain imaging techniques, electrophysiological methods, and experimental cognitive neuropsychology have nurtured the ongoing evolution and growth of Behavioral Neurology as a neurological subspecialty. Applying advances in basic neuroscience research, Behavioral Neurology is expanding our understanding of the neurobiological bases of cognition, emotions and social behavior. Although Behavioral Neurology and neuropsychiatry share some common areas of interest, the two fields differ in their scope and fundamental approaches, which reflect larger differences between neurology and psychiatry. Behavioral Neurology encompasses three general types of clinical -

640E Neurology Critical Care (Neuro Icu Core Rotation)

Course Code: 97348 640E NEUROLOGY CRITICAL CARE (NEURO ICU CORE ROTATION) Course Description: This elective in Neuro Critical Care and ICU is designed to give the student increased exposure and autonomy in care of the Neurocritical care patient, including the medical treatment in acute neurological patients. Students function as sub interns, becoming integral members of the ICU team, and several primary caregivers under supervision. Department: Neurology Prerequisites: Successful completion of 1st and 2nd year curriculum. Successful completion of the 3rd year neurology core rotation Restrictions: This course does not accept international students Course Director: Sara Stern-Nezer, MD, UC Irvine Medical Center 200 S. Manchester Ave., Suite #206, Orange, CA 92868 Phone: 714-456-3565 Fax: 714-456-6894 Email: [email protected] Instructing Faculty: Cyrus Dastur, MD HS Clinical Professor of Neurology Leonid Groysman, MD HS Clinical Professor of Neurology Yama Akbari, MD PhD Clinical Professor of Neurology Sara Stern-Nezer, MD HS Clinical Professor of Neurology Frank P K Hsu, MD, PhD, Chair and Clinical Professor of Neurological Surgery Kiarash Golshani, MD Assistant Clinical Professor of Neurological Surgery Jefferson Chen, MD Assistant Clinical Professor of Neurological Surgery Shuichi Suzuki, MD, PhD, Assistant Clinical Professor of Neurological Surgery Course Website: http://www.neurology.uci.edu/overview.html Who to Report to First Day: Sara Stern-Nezer, MD, Neurology Clerkship Director / Stephanie Makhlouf, Neurology Education Coordinator Location to Report on First Day: UC Irvine Medical Center- Neurology Department, Conference Room, 200 Manchester Ave., Suite 206, Orange, CA 92868 Time to Report on First Day: 7:30 am Site: UC Irvine Medical Center Periods Available: Throughout the year Duration: 4 weeks Number of Students: 1 per block Scheduling Coordinator: UC Irvine students must officially enroll for the course by contacting the Scheduling Coordinator via email or phone (714) 456-8462 to make a scheduling appointment.