MY9700691 CT of Pleural Abnormalities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pubid-1446077038.Pdf

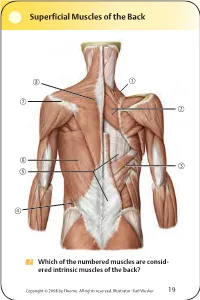

Superficial Muscles of the Back Which of the numbered muscles are consid- ered intrinsic muscles of the back? Copyright © 2008 by Thieme. All rights reserved. Illustrator: Karl Wesker 19 Superficial Muscles of the Back Posterior view. A Levator scapulae S Rhomboideus major D Serratus posterior inferior F Lumbar triangle, internal oblique G Thoracolumbar fascia, superficial layer H Latissimus dorsi J Scapular spine K Trapezius, transverse part Only the serratus posterior inferior is an intrinsic muscle of the back. The trapezius, latissimus dorsi, leva- tor scapulae, and rhomboideus muscles assist in move- ment of the shoulder or arm and are considered muscles of the upper limb. Fig. 2.1. Gilroy, MacPherson, Ross, Atlas of Anatomy, p. 22. Course of the Intercostal Nerves Copyright © 2008 by Thieme. All rights reserved. Illustrator: Markus Voll 39 Course of the Intercostal Nerves Coronal section. Anterior view. A Visceral pleura S Parietal pleura, diaphragmatic part D Diaphragm F Costodiaphragmatic recess G Endothoracic fascia H External intercostal J Costal groove K Intercostal vein, artery, and nerve Abnormal fluid collection in the pleural space (e.g., pleural effusion due to bronchial carcinoma) may necessitate the insertion of a chest tube. Generally, the optimal puncture site in a sitting patient is at the level of the 7th or 8th intercostal space on the posterior axillary line. The drain should always be introduced at the upper margin of a rib to avoid injuring the intercostal vein, artery, and nerve. Fig. 5.24. From Atlas of Anatomy, p. 59. Copyright ©2008 byThieme. Allrightsreserved. Illustrator: Markus Voll Right Lung 74 Right Lung Lateral and medial views. -

THORAX ANATOMY LAB 1: LEARNING OBJECTIVES Thoracic Wall, Pleural Cavities, and Lungs

THORAX ANATOMY LAB 1: LEARNING OBJECTIVES Thoracic Wall, Pleural Cavities, and Lungs Primary Learning Objectives 1. Define thorax and state the structures that form its anatomical boundaries. 2. Describe the locations and boundaries of the superior thoracic aperture (clinical: thoracic outlet) and the inferior thoracic aperture. Identify the costal arch (margin) and state the ribs that form the arch. 3. Identify and palpate the bones that compose the sternum (manubrium, body, and xiphoid process) and associated osteological features: jugular notch, clavicular notch, and sternal angle. 4. For the sternal angle, identify its associated vertebral level, state its anatomical relationship to the trachea and aorta, state its significance in creating an anatomical division of the mediastinum, and identify the ribs that join the sternum at its location. 5. Identify and palpate the clavicle, sternum, ribs, costal cartilages, intercostal spaces, and thoracic vertebrae. 6. Differentiate true ribs from false and floating ribs. 7. Identify the following osseous features on a rib: head, necK, rib (costal) tubercle, body, shaft, and the costal groove. 8. State the weaKest region of the rib that is commonly fractured and describe the anatomy and physiology involving flail chest. 9. Describe the possible clinical manifestations of supernumerary ribs. 10. Identify the following rib joints: costovertebral (costotransverse joint and vertebral body joint) and sternocostal. 11. Identify the transversus thoracis muscle, the external, internal, and innermost intercostal muscles, and state their innervation, blood supply, and functions. 12. State the structures that compose the neurovascular bundle within each intercostal space and identify each neurovascular bundle by number. 13. Identify the neurovascular bundle inferior to the twelfth rib and state the names of each structure composing the bundle (subcostal artery, subcostal vein, and subcostal nerve). -

On the Anatomy of Intercostal Spaces in Man and Certain Other Mammals1 by Prof

ON THE ANATOMY OF INTERCOSTAL SPACES IN MAN AND CERTAIN OTHER MAMMALS1 BY PROF. M. A. H. SIDDIQI, M.B., D.L.O., M.S., F.R.C.S. (ENG.) AND DR A. N. MULLICK, M.B., B.S. Anatomy Department, King George's Medical College, Lucknow (India) TIHE standard description of the anatomy of the intercostal space has been discussed by Stibbe in a paper recently published in this Journal(2,3). Prof. Walmsley in 1916(1) showed that the intercostal nerves do not lie in the plane between the internal and external intercostal muscles but deep to the internal intercostal, and that they are separated from the pleura by a deeper musculo-fascial plane consisting of subcostal, intercostal and transversus thoracis muscles from behind forwards. According to Davies, Gladstone and Stibbe (3) there are four musculo-fascial planes in each space and in each space the main nerve lies with a collateral nerve deep to the internal intercostal. As the above paper effected a change in the teaching of the anatomy of intercostal space, we carried out the following investigations on human as well as on certain other Mammalian intercostal spaces. DISSECTION OF HUMAN INTERCOSTAL SPACES Sixty thoraces of different ages were dissected. From some of them the intercostal spaces were cut out en bloc to facilitate dissection; in others the thoracic wall was dissected as a whole. In the case of the foetuses microscopic sections were made to locate the muscular planes and the nerves. The results of our dissection were as follows: I. Intercostal muscles (fig. -

The Pleura1 with Special Reference to Fibrothorax

Thorax (1970), 25, 515. The pleura1 With special reference to fibrothorax N. R. BARRETT Royal College of Surgeons of England We have met to honour and to remember Arthur always at his side; amongst the physicians, Sir Tudor Edwards, who died after the Second World Geoffrey Marshall helped him to found the War and who devoted much of his professional Thoracic Society in 1945. life to the advancement of thoracic surgery. Looking back upon the 1920s one can see that He lived and worked towards the end of an the emblems were not favourable for thoracic era when surgeons were 'prima donnas'. He was surgeons. J. E. H. Roberts and Tudor Edwards a man of handsome and commanding appear- had no beds of their own at the Brompton Hos- ance: his convictions *were strong and to his pital; they were at first at the beck and call of friends he was a staunch ally; the others he the physicians who decreed the operations they allowed to cultivate their own gardens. considered appropriate. The majority of these He was a pioneer in his own field and became were for general surgical conditions; little could one of the first thoracic surgeons in the United be done for chest diseases. But within a decade Kingdom to achieve an international reputation. the picture had changed: the Brompton had He deserved more recognition from his contem- become a Mecca for all who were interested in poraries in England than they gave him; indeed, his only honour was a medal from his colleagues in Norway. The reason was that thoracic surgery was not at first accepted as more than a foray into unlikely and hazardous territory. -

Powerpoint Handout: Lab 1, Thorax

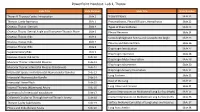

PowerPoint Handout: Lab 1, Thorax Slide Title Slide Number Slide Title Slide Number Thorax & Thoracic Cavity: Introduction Slide 2 Visceral Pleura Slide 21 Thoracic Cavity Apertures Slide 3 Pneumothorax, Pleural Effusion, Hemothorax Slide 22 Osseous Thorax: Sternum Slide 4 Types of Pneumothorax Slide 23 Osseous Thorax: Sternal Angle and Transverse Thoracic Plane Slide 5 Pleural Recesses Slide 24 Osseous Thorax: Ribs Slide 6 Costodiaphragmatic Recess and Costophrenic Angle Slide 25 Osseous Thorax: Ribs Slide 7 Pleurisy and Referred Pain Slide 26 Osseous Thorax: Ribs Slide 8 Diaphragm Introduction Slide 27 Supernumerary Ribs Slide 9 Diaphragm Apertures Slide 28 Osseous Thorax: Rib Joints Slide 10 Diaphragm Motor Innervation Slide 29 Muscular Thorax: Intercostal Muscles Slide 11 Diaphragm Movements Slide 30 Muscular Thorax: Intercostal Muscles (Continued) Slide 12 Diaphragm Sensory Innervation Slide 31 Intercostal Spaces and Intercostal Neurovascular Bundles Slide 13 Lung Surfaces Slide 32 Intercostal Neurovascular Bundle Slide 14 Root of the Lung Slide 33 Intercostal Nerve Block Slide 15 Slide 34 Internal Thoracic (Mammary) Artery Slide 16 Lung Lobes and Fissures Summary of of Intercostal Vasculature Slide 17 Contact Impressions on Mediastinal Lung Surface (Right) Slide 35 Collateral Circulation Through Internal Thoracic Artery Slide 18 Contact Impressions on Mediastinal Lung Surface (Left) Slide 36 Thoracic Cavity Subdivisions Slide 19 Surface Anatomy Correlates of Lung Lobes and Fissures Slide 37 Pleura and Endothoracic Fascia Slide 20 Lung Auscultation Slide 38 Thorax & Thoracic Cavity: Introduction The thorax refers to the region of the body between the neck https://3d4medic.al/enFsQOFf and the abdomen. The thoracic cavity is an irregularly shaped cylinder enclosed by the musculoskeletal walls of the thorax and the diaphragm. -

Thoracic Wall

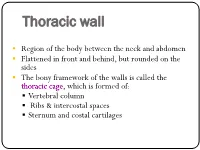

Thoracic wall . Region of the body between the neck and abdomen . Flattened in front and behind, but rounded on the sides . The bony framework of the walls is called the thoracic cage, which is formed of: . Vertebral column . Ribs & intercostal spaces . Sternum and costal cartilages Superiorly: It communicates1st rib with the neck through an opening bounded:1 . Posteriorly by 1st thoracic vertebra . Laterally by medial border of the 1st ribs and their costal cartilages . Anteriorly by superior border of manubrium sterni Suprapleural This opening is occupied: membrane . In the midline, by the structures that pass between the neck and the thorax . On either sides, it is closed by a dense suprapleural membrane Suprapleural Membrane . Tent shaped dense fascial sheet that covers the apex of each lung. An extension of the endothoracic fascia . Extends approximately an inch superior to the superior thoracic aperture . It is attached: • The thoracic cage: . Protects the lungs, heart and large vessels . Provides attachment to the muscles of thorax, upper limb, abdomen & back • The cavity of thorax is divided into: • A median partition, the mediastinum • Laterally placed pleurae & lungs Cutaneous Nerves Anterior wall: . Above the level of sternal angle: Supraclavicular nerves . Below the level of sternal angle: Segmental innervation by anterior and lateral cutaneous branches of the intercostal nerves Posterior wall: . Segmental innervation by posterior rami of the thoracic spinal nerves nerves The Intercostal Space Intercostal Space It is the space between two ribs Since there are 12 ribs on each side, there are 11 intercostal spaces. Each space contains: . Intercostal muscles . Intercostal neurovascular bundle . Lymphatics Intercostal muscles • External Intercostal • Internal Intercostal • Innermost Intercostal Supplied by corresponding intercostal nerves Action: • Tend to pull the ribs nearer to each other . -

1. Anatomical Basis of Thoracic Surgery

BWH 2015 GENERAL SURGERY RESIDENCY PROCEDURAL ANATOMY COURSE 1. ANATOMICAL BASIS OF THORACIC SURGERY Contents Lab objectives ............................................................................................................................................... 2 Knowledge objectives ............................................................................................................................... 2 Skills objectives ......................................................................................................................................... 2 Preparation for lab ....................................................................................................................................... 2 1.1 BASIC PRINCIPLES OF ANATOMICAL ORGANIZATION ............................................................................ 4 1.2 THORACIC CAVITY AND CHEST WALL ..................................................................................................... 9 1.3 PLEURA AND LUNGS ............................................................................................................................. 13 1.4 ORGANIZATION OF THE MEDIASTINUM .............................................................................................. 19 1.5 ANTERIOR mediastinum ....................................................................................................................... 23 Thymus ................................................................................................................................................... -

Endoscopic Harvesting of the Left Internal Mammary Artery

Masters of Cardiothoracic Surgery Endoscopic harvesting of the left internal mammary artery Tomasz Hrapkowicz1, Gianluigi Bisleri2 1Division of Cardiac Surgery and Transplantology, Silesian Center for Heart Diseases, Zabrze, Poland; 2Division of Cardiac Surgery, University of Brescia Medical School, Brescia, Italy Corresponding to: Dr. Tomasz Hrapkowicz. Division of Cardiac Surgery and Transplantology, Silesian Center for Heart Diseases, Zabrze, Poland. Email: [email protected]. Minimally invasive coronary artery bypass grafting via left anterior small thoracotomy is routinely performed on patients with single coronary artery disease, but recently has been expanded to a larger population as a part of a hybrid treatment in multivessel coronary artery disease. While the methods of internal mammary artery harvesting used in these operations can be different, the endoscopic method is more advantageous than operations performed by direct vision, and thus should be used as a technique of choice. In this article, we present detailed description of endoscopic mammary artery harvesting focusing on anatomical and technical aspects. Keywords: Minimally invasive coronary artery bypass grafting; endoscopic mammary artery harvesting; minimally invasive cardiac surgery Submitted Jun 30, 2013. Accepted for publication Jul 16, 2013. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2225-319X.2013.07.11 Scan to your mobile device or view this article at: http://www.annalscts.com/article/view/2422/3288 Introduction perform such operations via a minimally invasive approach, particularly through a left anterior small thoracotomy Minimally invasive direct coronary artery bypass (MIDCAB) (2-5). Several reports have confirmed the safety and efficacy grafting via an anterolateral thoracotomy was first of such an approach, also in the long term (6-12). -

Anatomy of the Thoracic Wall, Pulmonary Cavities, and Mediastinum

3 Anatomy of the Thoracic Wall, Pulmonary Cavities, and Mediastinum KENNETH P. ROBERTS, PhD AND ANTHONY J. WEINHAUS, PhD CONTENTS INTRODUCTION OVERVIEW OF THE THORAX BONES OF THE THORACIC WALL MUSCLES OF THE THORACIC WALL NERVES OF THE THORACIC WALL VESSELS OF THE THORACIC WALL THE SUPERIOR MEDIASTINUM THE MIDDLE MEDIASTINUM THE ANTERIOR MEDIASTINUM THE POSTERIOR MEDIASTINUM PLEURA AND LUNGS SURFACE ANATOMY SOURCES 1. INTRODUCTION the thorax and its associated muscles, nerves, and vessels are The thorax is the body cavity, surrounded by the bony rib covered in relationship to respiration. The surface anatomical cage, that contains the heart and lungs, the great vessels, the landmarks that designate deeper anatomical structures and sites esophagus and trachea, the thoracic duct, and the autonomic of access and auscultation are reviewed. The goal of this chapter innervation for these structures. The inferior boundary of the is to provide a complete picture of the thorax and its contents, thoracic cavity is the respiratory diaphragm, which separates with detailed anatomy of thoracic structures excluding the heart. the thoracic and abdominal cavities. Superiorly, the thorax A detailed description of cardiac anatomy is the subject of communicates with the root of the neck and the upper extrem- Chapter 4. ity. The wall of the thorax contains the muscles involved with 2. OVERVIEW OF THE THORAX respiration and those connecting the upper extremity to the axial skeleton. The wall of the thorax is responsible for protecting the Anatomically, the thorax is typically divided into compart- contents of the thoracic cavity and for generating the negative ments; there are two bilateral pulmonary cavities; each contains pressure required for respiration. -

The Five Diaphragms in Osteopathic Manipulative Medicine: Myofascial Relationships, Part 2

Open Access Review Article DOI: 10.7759/cureus.7795 The Five Diaphragms in Osteopathic Manipulative Medicine: Myofascial Relationships, Part 2 Bruno Bordoni 1 1. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Foundation Don Carlo Gnocchi, Milan, ITA Corresponding author: Bruno Bordoni, [email protected] Abstract The article continues the anatomical review of the anterolateral myofascial connections of the five diaphragms in osteopathic manipulative medicine (OMM), with the most up-to-date scientific information. The postero-lateral myofascial relationships have been illustrated previously in the first part. The article emphasizes some key OMM concepts; the attention of the clinician must not stop at the symptom or local pain but, rather, verify where the cause that leads to the symptom arises, thanks to the myofascial systems. Furthermore, it is important to remember that the human body is a unity and we should observe the patient not as a series of disconnected segments but as multiple and different elements that work in unison; a dysfunction of tissue will adversely affect neighboring and distant tissues. The goal of the work is to lay solid foundations for the OMM and the five-diaphragm approach showing the myofascial continuity of the human body. Categories: Medical Education, Anatomy, Osteopathic Medicine Keywords: diaphragm, osteopathic, fascia, myofascial, fascintegrity, physiotherapy Introduction And Background The approach to the five diaphragms in osteopathic manipulative medicine (OMM) is part of the respiratory- circulatory model, whose principle is the free movement of body fluids to maintain or improve patient health [1-2]. The OMM philosophy is based on patient-centred care, applying scientific knowledge and clinical experience [3-4]. -

Chest Pain in Patients with COPD: the Fascia's Subtle Silence

Journal name: International Journal of COPD Article Designation: Commentary Year: 2018 Volume: 13 International Journal of COPD Dovepress Running head verso: Bordoni et al Running head recto: Chest pain in patients with COPD open access to scientific and medical research DOI: 156729 Open Access Full Text Article COMMENTARY Chest pain in patients with COPD: the fascia’s subtle silence Bruno Bordoni1 Abstract: COPD is a progressive condition that leads to a pathological degeneration of the Fabiola Marelli2,3 respiratory system. It represents one of the most important causes of mortality and morbidity Bruno Morabito2–4 in the world, and it is characterized by the presence of many associated comorbidities. Recent Roberto Castagna2 studies emphasize the thoracic area as one of the areas of the body concerned by the presence of pain with percentages between 22% and 54% in patients with COPD. This article analyzes 1Foundation Don Carlo Gnocchi IRCCS, Department of Cardiology, the possible causes of mediastinal pain, including those less frequently taken into consideration, Institute of Hospitalization and Care which concern the role of the fascial system of the mediastinum. The latter can be a source with Scientific Address, Milan, Italy; of pain especially when a chronic pathology is altering the structure of the connective tissue. 2CRESO, School of Osteopathic Centre for Research and Studies, We conclude that to consider the fascia in daily clinical activity may improve the therapeutic Gorla Minore, Italy; 3CRESO, School approach toward the patient. of Osteopathic Centre for Research COPD, diaphragm, thoracic pain, fascia, muscle pain and Studies, Fano, Italy; 4Department Keywords: For personal use only. -

Latin Term Latin Synonym UK English Term American English Term English

General Anatomy Latin term Latin synonym UK English term American English term English synonyms and eponyms Notes Termini generales General terms General terms Verticalis Vertical Vertical Horizontalis Horizontal Horizontal Medianus Median Median Coronalis Coronal Coronal Sagittalis Sagittal Sagittal Dexter Right Right Sinister Left Left Intermedius Intermediate Intermediate Medialis Medial Medial Lateralis Lateral Lateral Anterior Anterior Anterior Posterior Posterior Posterior Ventralis Ventral Ventral Dorsalis Dorsal Dorsal Frontalis Frontal Frontal Occipitalis Occipital Occipital Superior Superior Superior Inferior Inferior Inferior Cranialis Cranial Cranial Caudalis Caudal Caudal Rostralis Rostral Rostral Apicalis Apical Apical Basalis Basal Basal Basilaris Basilar Basilar Medius Middle Middle Transversus Transverse Transverse Longitudinalis Longitudinal Longitudinal Axialis Axial Axial Externus External External Internus Internal Internal Luminalis Luminal Luminal Superficialis Superficial Superficial Profundus Deep Deep Proximalis Proximal Proximal Distalis Distal Distal Centralis Central Central Periphericus Peripheral Peripheral One of the original rules of BNA was that each entity should have one and only one name. As part of the effort to reduce the number of recognized synonyms, the Latin synonym peripheralis was removed. The older, more commonly used of the two neo-Latin words was retained. Radialis Radial Radial Ulnaris Ulnar Ulnar Fibularis Peroneus Fibular Fibular Peroneal As part of the effort to reduce the number of synonyms, peronealis and peroneal were removed. Because perone is not a recognized synonym of fibula, peronealis is not a good term to use for position or direction in the lower limb. Tibialis Tibial Tibial Palmaris Volaris Palmar Palmar Volar Volar is an older term that is not used for other references such as palmar arterial arches, palmaris longus and brevis, etc.