Powerpoint Handout: Lab 1, Thorax

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Anklyosed Spine: Fractures in DISH and Anklyosing Spondylitis

The Anklyosed Spine: Fractures in DISH and Anklyosing Spondylitis Lee F. Rogers, MD ACCR, Oct 26, 2012 Dallas, Texas Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) and ankylosing spondylitis (AS) are the most common diseases associated with spinal ankylosis. While they share the characteristic of ankylosis they are, in fact two separate diseases with distinct clinical, pathologic, and radiologic features. DISH: Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis is a disease of older persons characterized by extensive ossification of the paraspinal ligaments anteriorly and laterally, bridging the intervening disc spaces. Bony bridging may be continuous or discontinuous. The anterior cortex of the vertebral body can be seen within the ossification. These findings are much more pronounced in the thoracic and lower cervical spine than in the lumbar area. Minor expressions of this disorder are commonly encountered in the mid-dorsal spine on lateral views of the chest. DISH characteristically spares the SI joints. The SI joints remain patent and clearly visible on radiographs or CT even in the presence of extensive disease in the thoracolumbar and cervical spine. DISH is also characterized by enthesopathy; ossification of ligaments or tendon insertions, forming so-called entheses. These appear as whiskering of the iliac crest, ischial tuberosites and greater trochanters. The radiographic appearance bears a superficial resemblance to that of AS. In DISH the spinal ossification is very irregular and unlike the thin, vertical syndesmophytes see in AS. The relative absence of changes in the lumbosacral spine, the patency of the SI joints, and absence of ankylosis of the facet and costovertebral joints should allow differentiation of DISH from AS. -

Diapositiva 1

Thoracic Cage and Thoracic Inlet Professor Dr. Mario Edgar Fernández. Parts of the body The Thorax Is the part of the trunk betwen the neck and abdomen. Commonly the term chest is used as a synonym for thorax, but it is incorrect. Consisting of the thoracic cavity, its contents, and the wall that surrounds it. The thoracic cavity is divided into 3 compartments: The central mediastinus. And the right and left pulmonary cavities. Thoracic Cage The thoracic skeleton forms the osteocartilaginous thoracic cage. Anterior view. Thoracic Cage Posterior view. Summary: 1. Bones of thoracic cage: (thoracic vertebrae, ribs, and sternum). 2. Joints of thoracic cage: (intervertebral joints, costovertebral joints, and sternocostal joints) 3. Movements of thoracic wall. 4. Thoracic cage. Thoracic apertures: (superior thoracic aperture or thoracic inlet, and inferior thoracic aperture). Goals of the classes Identify and describe the bones of the thoracic cage. Identify and describe the joints of thoracic cage. Describe de thoracic cage. Describe the thoracic inlet and identify the structures passing through. Vertebral Column or Spine 7 cervical. 12 thoracic. 5 lumbar. 5 sacral 3-4 coccygeal Vertebrae That bones are irregular, 33 in number, and received the names acording to the position which they occupy. The vertebrae in the upper 3 regions of spine are separate throughout the whole of life, but in sacral anda coccygeal regions are in the adult firmly united in 2 differents bones: sacrum and coccyx. Thoracic vertebrae Each vertebrae consist of 2 essential parts: An anterior solid segment: vertebral body. The arch is posterior an formed of 2 pedicles, 2 laminae supporting 7 processes, and surrounding a vertebral foramen. -

Ligaments of the Costovertebral Joints Including Biomechanics, Innervations, and Clinical Applications: a Comprehensive Review W

Open Access Review Article DOI: 10.7759/cureus.874 Ligaments of the Costovertebral Joints including Biomechanics, Innervations, and Clinical Applications: A Comprehensive Review with Application to Approaches to the Thoracic Spine Erfanul Saker 1 , Rachel A. Graham 2 , Renee Nicholas 3 , Anthony V. D’Antoni 2 , Marios Loukas 1 , Rod J. Oskouian 4 , R. Shane Tubbs 5 1. Department of Anatomical Sciences, St. George's University School of Medicine, Grenada, West Indies 2. Department of Anatomy, The Sophie Davis School of Biomedical Education 3. Department of Physical Therapy, Samford University 4. Neurosurgery, Complex Spine, Swedish Neuroscience Institute 5. Neurosurgery, Seattle Science Foundation Corresponding author: Erfanul Saker, [email protected] Abstract Few studies have examined the costovertebral joint and its ligaments in detail. Therefore, the following review was performed to better elucidate their anatomy, function and involvement in pathology. Standard search engines were used to find studies concerning the costovertebral joints and ligaments. These often- overlooked ligaments of the body serve important functions in maintaining appropriate alignment between the ribs and spine. With an increasing interest in minimally invasive approaches to the thoracic spine and an improved understanding of the function and innervation of these ligaments, surgeons and clinicians should have a good working knowledge of these structures. Categories: Neurosurgery, Orthopedics, Rheumatology Keywords: costovertebral joint, spine, anatomy, thoracic Introduction And Background The costovertebral joint ligaments are relatively unknown and frequently overlooked anatomical structures [1]. Although small and short in size, they are abundant, comprising 108 costovertebral ligaments in the normal human thoracic spine, and they are essential to its stability and function [2-3]. -

Pubid-1446077038.Pdf

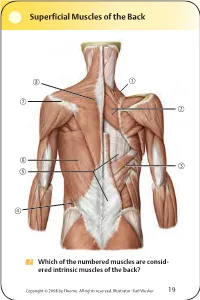

Superficial Muscles of the Back Which of the numbered muscles are consid- ered intrinsic muscles of the back? Copyright © 2008 by Thieme. All rights reserved. Illustrator: Karl Wesker 19 Superficial Muscles of the Back Posterior view. A Levator scapulae S Rhomboideus major D Serratus posterior inferior F Lumbar triangle, internal oblique G Thoracolumbar fascia, superficial layer H Latissimus dorsi J Scapular spine K Trapezius, transverse part Only the serratus posterior inferior is an intrinsic muscle of the back. The trapezius, latissimus dorsi, leva- tor scapulae, and rhomboideus muscles assist in move- ment of the shoulder or arm and are considered muscles of the upper limb. Fig. 2.1. Gilroy, MacPherson, Ross, Atlas of Anatomy, p. 22. Course of the Intercostal Nerves Copyright © 2008 by Thieme. All rights reserved. Illustrator: Markus Voll 39 Course of the Intercostal Nerves Coronal section. Anterior view. A Visceral pleura S Parietal pleura, diaphragmatic part D Diaphragm F Costodiaphragmatic recess G Endothoracic fascia H External intercostal J Costal groove K Intercostal vein, artery, and nerve Abnormal fluid collection in the pleural space (e.g., pleural effusion due to bronchial carcinoma) may necessitate the insertion of a chest tube. Generally, the optimal puncture site in a sitting patient is at the level of the 7th or 8th intercostal space on the posterior axillary line. The drain should always be introduced at the upper margin of a rib to avoid injuring the intercostal vein, artery, and nerve. Fig. 5.24. From Atlas of Anatomy, p. 59. Copyright ©2008 byThieme. Allrightsreserved. Illustrator: Markus Voll Right Lung 74 Right Lung Lateral and medial views. -

Diaphragm and Intercostal Muscles

Diaphragm and intercostal muscles Dr. Heba Kalbouneh Associate Professor of Anatomy and Histology Skeletal System Adult Human contains 206 Bones 2 parts: Axial skeleton (axis): Skull, Vertebral column, Thoracic cage Appendicular skeleton: Bones of upper limb Bones of lower limb Dr. Heba Kalbouneh Structure of Typical Vertebra Body Vertebral foramen Pedicle Transverse process Spinous process Lamina Dr. Heba Kalbouneh Superior articular process Intervertebral disc Dr. Heba Inferior articular process Dr. Heba Facet joints are between the superior articular process of one vertebra and the inferior articular process of the vertebra directly above it Inferior articular process Superior articular process Dr. Heba Kalbouneh Atypical Vertebrae Atlas (1st cervical vertebra) Axis (2nd cervical vertebra) Dr. Heba Atlas (1st cervical vertebra) Communicates: sup: skull (atlanto-occipital joint) inf: axis (atlanto-axial joint) Atlas (1st cervical vertebra) Characteristics: 1. no body 2. no spinous process 3. ant. & post. arches 4. 2 lateral masses 5. 2 transverse foramina Typical cervical vertebra Specific to the cervical vertebra is the transverse foramen (foramen transversarium). is an opening on each of the transverse processes which gives passage to the vertebral artery Thoracic Cage - Sternum (G, sternon= chest bone) -12 pairs of ribs & costal cartilages -12 thoracic vertebrae Manubrium Body Sternum: Flat bone 3 parts: Xiphoid process Dr. Heba Kalbouneh Dr. Heba Kalbouneh The external intercostal muscle forms the most superficial layer. Its fibers are directed downward and forward from the inferior border of the rib above to the superior border of the rib below The muscle extends forward to the costal cartilage where it is replaced by an aponeurosis, the anterior (external) intercostal membrane Dr. -

Chapter 21 Fractures of the Upper Thoracic Spine: Approaches and Surgical Management

Chapter 21 Fractures of the Upper Thoracic Spine: Approaches and Surgical Management Sean D Christie, M.D., John Song, M.D., and Richard G Fessler, M.D., Ph.D. INTRODUCTION Fractures occurring in the thoracic region account for approximately 17 to 23% of all traumatic spinal fractures (1), with 22% of traumatic spinal fractures occurring between T1 and T4 (16). More than half of these fractures result in neurological injury, and almost three-quarters of those impaired suffer from complete paralysis. Obtaining surgical access to the anterior vertebral elements of the upper thoracic vertebrae (T1–T6) presents a unique anatomic challenge. The thoracic cage, which narrows significantly as it approaches the thoracic inlet, has an intimate association between the vertebral column and the superior mediastinal structures. The supraclavicular, transmanubrial, transthoracic, and lateral parascapular extrapleural approaches each provide access to the anterior vertebral elements of the upper thoracic vertebrae. However, each of these approaches has distinct advantages and disadvantages and their use should be tailored to each individual patient’s situation. This chapter reviews these surgical approaches. Traditional posterior approaches are illustrated in Figure 21.1, but will not be discussed in depth here. ANATOMIC CONSIDERATIONS AND STABILITY The upper thoracic spine possesses unique anatomic and biomechanical properties. The anterior aspects of the vertebral bodies are smaller than the posterior aspects, which contribute to the physiological kyphosis present in this region of the spine. Furthermore, this orientation results in a ventrally positioned axis of rotation, predisposing this region to compression injuries. The combination and interaction of the vertebral bodies, ribs, and sternum increase the inherent biomechanical stability of this segment of the spine to 2 to 3 times that of the thoracolumbar junction. -

How to Perform a Transrectal Ultrasound Examination of the Lumbosacral and Sacroiliac Joints

DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING How to Perform a Transrectal Ultrasound Examination of the Lumbosacral and Sacroiliac Joints Erik H.J. Bergman, DVM, Diplomate ECAR, Associate Member LA-ECVDI*; Sarah M. Puchalski, DVM, Diplomate ACVR; and Jean-Marie Denoix, DVM, PhD, Agre´ge´, Associate Member LA-ECVDI Authors’ addresses: Lingehoeve Veldstraat 3 Lienden 4033 AK, The Netherlands (Bergman); Uni- versity of California, Davis, One Shields Avenue, School of Veterinary Medicine, Davis, CA 95616 (Puchalski); E´ cole Nationale Ve´te´rinaire d’Alfort, 7 Avenue du Ge´ne´ral de Gaulle, 94700 Maisons- Alfort, France (Denoix); e-mail: [email protected]. *Corresponding and presenting author. © 2013 AAEP. 1. Introduction have allowed for identification of these structures 5 There is increasing interest in pathology of the and the inter-transverse joints. These authors urge lumbosacral and sacroiliac joints giving rise to stiff- caution in the interpretation of lesions identified on ness and/or lameness and decreased performance radiography in the absence of other diagnostic im- in equine sports medicine.1–3 Pain arising from aging and clinical examination. Nuclear scintigra- these regions can be problematic alone or in con- phy is an important component of work-up for junction with lameness arising from other sites sacroiliac region pain, but limitations exist. Sev- 9,10 (thoracolumbar spine, hind limbs, or forelimbs).4 eral reports exist detailing the anatomy and tech- Localization of pain to this region is critically impor- nique findings in normal horses11,12 and findings in tant through clinical assessment, diagnostic anes- lame horses.13 Patient motion, camera positioning, thesia, and imaging. and muscle asymmetry can cause errors in interpre- In general, diagnostic imaging of the axial skele- tation. -

THORAX ANATOMY LAB 1: LEARNING OBJECTIVES Thoracic Wall, Pleural Cavities, and Lungs

THORAX ANATOMY LAB 1: LEARNING OBJECTIVES Thoracic Wall, Pleural Cavities, and Lungs Primary Learning Objectives 1. Define thorax and state the structures that form its anatomical boundaries. 2. Describe the locations and boundaries of the superior thoracic aperture (clinical: thoracic outlet) and the inferior thoracic aperture. Identify the costal arch (margin) and state the ribs that form the arch. 3. Identify and palpate the bones that compose the sternum (manubrium, body, and xiphoid process) and associated osteological features: jugular notch, clavicular notch, and sternal angle. 4. For the sternal angle, identify its associated vertebral level, state its anatomical relationship to the trachea and aorta, state its significance in creating an anatomical division of the mediastinum, and identify the ribs that join the sternum at its location. 5. Identify and palpate the clavicle, sternum, ribs, costal cartilages, intercostal spaces, and thoracic vertebrae. 6. Differentiate true ribs from false and floating ribs. 7. Identify the following osseous features on a rib: head, necK, rib (costal) tubercle, body, shaft, and the costal groove. 8. State the weaKest region of the rib that is commonly fractured and describe the anatomy and physiology involving flail chest. 9. Describe the possible clinical manifestations of supernumerary ribs. 10. Identify the following rib joints: costovertebral (costotransverse joint and vertebral body joint) and sternocostal. 11. Identify the transversus thoracis muscle, the external, internal, and innermost intercostal muscles, and state their innervation, blood supply, and functions. 12. State the structures that compose the neurovascular bundle within each intercostal space and identify each neurovascular bundle by number. 13. Identify the neurovascular bundle inferior to the twelfth rib and state the names of each structure composing the bundle (subcostal artery, subcostal vein, and subcostal nerve). -

The Effect of Training on Lumbar Spine Posture and Intervertebral Disc Degeneration in Active-Duty Marines

The Effect of Training on Lumbar Spine Posture and Intervertebral Disc Degeneration in Active-Duty Marines Ana E. Rodriguez-Soto, PhDc, David B. Berry, MScc, Rebecca Jaworski, PhDd,1, Andrew Jensen, MScd,g,2, Christine B. Chung, MDe,f, Brenda Niederberger, MAd,g, Aziza Qadirh, Karen R. Kelly, PT, PhDd,g , Samuel R. Ward, PT, PhDa,b,c aDepartments of Radiology, bOrthopaedic Surgery, and cBioengineering University of California, San Diego 9500 Gilman Drive (0610), La Jolla, CA 92093 dDepartment of Warfighter Performance, Naval Health Research Center 140 Sylvester Road, San Diego, CA 92106-3521 eDepartment of Radiology, Veteran Administration San Diego Healthcare System 3350 La Jolla Village Dr., San Diego, CA 92161 fDepartment of Radiology, University of California, San Diego Medical Center 408 Dickinson Street, San Diego, CA 92103-8226 gSchool of Exercise and Nutritional Sciences, San Diego State University ENS Building room 351, 5500 Campanile, San Diego, CA 92182-7251 hVital Imaging Center 5395 Ruffin Rd Suite 100, San Diego CA 92123 Ana Elvira Rodriguez-Soto, PhD E-mail: [email protected] David Barnes Berry, MS E-mail: [email protected] Rebecca Jaworski, PhD E-mail: [email protected] Present Address: 1Office of the Naval Inspector General 1254 9th St. SE, Washington Navy Yard, DC 90374-5006 Andrew Jensen, MS E-mail: [email protected] Present address: 2Department of Biological Sciences, University of Southern California PED 107 3560 Watt Way, Los Angeles, CA 90089-0652 Christine B. Chung, MD E-mail: [email protected] Brenda Niederberger, MA E-mail: [email protected] Aziza Qadir E-mail: [email protected] Karen R. -

Canine Thoracic Costovertebral and Costotransverse Joints Three Case Reports of Dysfunction and Manual Therapy Guidelines for A

Topics in Compan An Med 29 (2014) 1–5 Topical review Canine Thoracic Costovertebral and Costotransverse Joints: Three Case Reports of Dysfunction and Manual Therapy Guidelines for Assessment and Treatment of These Structures Laurie Edge-Hughes, BScPT, MAnimSt (Animal Physiotherapy), CAFCI, CCRTn Keywords: The costovertebral and costotransverse joints receive little attention in research. However, pain costovertebral associated with rib articulation dysfunction is reported to occur in human patients. The anatomic costotransverse structures of the canine rib joints and thoracic spine are similar to those of humans. As such, it is ribs physical therapy proposed that extrapolation from human physical therapy practice could be used for the assessment and rehabilitation treatment of the canine patient with presumed rib joint pain. This article presents 3 case studies that manual therapy demonstrate signs of rib dysfunction and successful treatment using primarily physical therapy manual techniques. General assessment and select treatment techniques are described. & 2014 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. The Canine Fitness Centre Ltd, Calgary, Alberta, Canada nAddress reprint requests to Laurie Edge-Hughes, BScPT, MAnimSt (Animal Physiotherapy), CAFCI, CCRT, The Canine Fitness Centre Ltd, 509—42nd Ave SE, Calgary, Alberta, Canada T2G 1Y7 E-mail: [email protected] The articular structures of the thorax comprise facet joints, the erect spine and further presented that in reviewing the literature, intervertebral disc, and costal joints. Little research has been they were unable to find mention of natural development of conducted on these joints in human or animal medicine. However, idiopathic scoliosis in quadrupeds; however, there are reports of clinical case presentations in human journals, manual therapy avian models and adolescent models in man. -

Posterior Longitudinal Ligament Status in Cervical Spine Bilateral Facet Dislocations

Thomas Jefferson University Jefferson Digital Commons Department of Orthopaedic Surgery Faculty Papers Department of Orthopaedic Surgery November 2005 Posterior longitudinal ligament status in cervical spine bilateral facet dislocations John A. Carrino Harvard Medical School & Brigham and Women's Hospital Geoffrey L. Manton Thomas Jefferson University Hospital William B. Morrison Thomas Jefferson University Hospital Alex R. Vaccaro Thomas Jefferson University Hospital and The Rothman Institute Mark E. Schweitzer New York University & Hospital for Joint Diseases Follow this and additional works at: https://jdc.jefferson.edu/orthofp Part of the Orthopedics Commons LetSee next us page know for additional how authors access to this document benefits ouy Recommended Citation Carrino, John A.; Manton, Geoffrey L.; Morrison, William B.; Vaccaro, Alex R.; Schweitzer, Mark E.; and Flanders, Adam E., "Posterior longitudinal ligament status in cervical spine bilateral facet dislocations" (2005). Department of Orthopaedic Surgery Faculty Papers. Paper 3. https://jdc.jefferson.edu/orthofp/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Jefferson Digital Commons. The Jefferson Digital Commons is a service of Thomas Jefferson University's Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL). The Commons is a showcase for Jefferson books and journals, peer-reviewed scholarly publications, unique historical collections from the University archives, and teaching tools. The Jefferson Digital Commons allows researchers and interested readers anywhere in the world to learn about and keep up to date with Jefferson scholarship. This article has been accepted for inclusion in Department of Orthopaedic Surgery Faculty Papers by an authorized administrator of the Jefferson Digital Commons. For more information, please contact: [email protected]. -

OMM PRACTICAL EXAM Saroj Misra, DO, FACOFP Rachel Nixon, DO Marissa Rogers, DO Family Medicine Goals/Objectives

OMM PRACTICAL EXAM Saroj Misra, DO, FACOFP Rachel Nixon, DO Marissa Rogers, DO Family Medicine Goals/Objectives • Review Exam Day procedure • Understand scoring process • Discuss possible cases and 2 OMM techniques that may be used for each case Disclaimer: The material being presented is NOT necessarily identical to what will be tested upon. We are not affiliated with the actual exam. This is our approach to the practical exam material. EXAM DAY Exam day • You will be assigned a time slot based on your last name • You will select a partner within your time slot • May not partner with a spouse or relative • You will be asked to sign a waiver stating that if you choose to do HVLA you will not perform the corrective “thrust” • You will then stand in line with your partner and await entering the testing room Exam day • There will be two rooms - one in which you will review cases and the second where you will be tested • Once you enter the first room you will not be able to leave • If you DO leave, both you and your partner will be given new cases Exam day • You will be given 3 cases: • Spine • Extremities • Systemic Disease • You will enter your name, ID number and your partners ID number on each case before turning them over Exam day • Each case will have the following information: • HPI • PMH • PSH • FHx • SocHx • There will be multiple choice for the best answer for your diagnosis • You will have 20 minutes to choose the best answer and plan a treatment strategy for each of your cases Exam day • After the 20 minutes are complete, you will