WESTERN CIVILIZATION: an INTRODUCTION This Course Is Called Western Civilization I, So Perhaps the first Thing That We Should Do Is Define What This Means

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Aristocratic Warlike Ethos of Indo-Europeans and the Primordial Origins of Western Civilization—Part Two Ricardo Duchesne [email protected]

Comparative Civilizations Review Volume 61 Article 3 Number 61 Fall 2009 10-1-2009 The Aristocratic Warlike Ethos of Indo-Europeans and the Primordial Origins of Western Civilization—Part Two Ricardo Duchesne [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr Recommended Citation Duchesne, Ricardo (2009) "The Aristocratic Warlike Ethos of Indo-Europeans and the Primordial Origins of Western Civilization—Part Two," Comparative Civilizations Review: Vol. 61 : No. 61 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr/vol61/iss61/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the All Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Comparative Civilizations Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Duchesne: The Aristocratic Warlike Ethos of Indo-Europeans and the Primordi The Aristocratic Warlike Ethos of Indo-Europeans and the Primordial Origins of Western Civilization—Part Two1 Ricardo Duchesne [email protected] Western civilization has been the single most war-ridden, war- dominated, and militaristic civilization in all human history. Robert Nisbet [Mycenaean] society was not the society of a sacred city, but that of a military aristocracy. It is the heroic society of the Homeric epic, and in Homer's world there is no room for citizen or priest or merchant, but only for the knight and his retainers, for the nobles and the Zeus born kings, 'the sackers of cities.' Christopher Dawson [T]he Greek knows the artist only in personal struggle... What, for example, is of particular importance in Plato's dialogues is mostly the result of a contest with the art of orators, the Sophists, the dramatists of his time, invented for the purpose of his finally being able to say: 'Look: I, too, can do what my great rivals can do; yes, I can do it better than them. -

SAMPLER GUIDE GUIDE HMH Social Studies

HMH SOCIAL STUDIES CIVILIZATIONS TEACHER’STEACHER’SSAMPLER GUIDE GUIDE HMH SOCIAL STUDIES WORLD CIVI LIZATIONS TEACHER’SSAMPLER GUIDE HMH Social Studies World Civilizations Explore Online Dashboard to Experience the Power of Designed for today’s digital natives, HMH® Social Studies offers you and World Civilizations your students a robust, intuitive online experience. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt® is changing the way students experience social studies. By delivering an immersive experience through compelling narratives enriched with media, we’re connecting students to history through experiences that are energizing, inspiring, and memorable activities. The following pages highlight some digital tools and instructional support that will help students approach history through active inquiry so they can connect to the past while becoming active and informed citizens for the future. The Online Student Edition is the primary learning portal. More than just the digital version of a textbook, the Online Student Edition serves as the primary learning portal for students. The narrative is supported by a wealth of multimedia and learning resources to bring history to life and give your students the tools they need to succeed. Your personalized Teacher 1. Discover—Quickly access content and search program resources Dashboard is organized into 2. Assignments—Create assignments and track progress of Bringing Content to Life four main sections: assignments HISTORY® videos and Multimedia Connections bring 3. Data & Reports—Monitor students’ daily progress content to life through primary source footage, dramatic 4. HMH Drive—Personalize your experience and upload your own storytelling, and expert testimonials. content FM 2 WORLD CIVILIZATIONS FM 3 In-Depth Understanding The Guided Reading Workbook and Spanish/English Guided Reading Workbook Close Read Screencasts model an analytical offer students lesson summaries with conversation about primary sources. -

Contents Humanities Notes

Humanities Notes Humanities Seminar Notes - this draft dated 24 May 2021 - more recent drafts will be found online Contents 1 2007 11 1.1 October . 11 1.1.1 Thucydides (2007-10-01 12:29) ........................ 11 1.1.2 Aristotle’s Politics (2007-10-16 14:36) ..................... 11 1.2 November . 12 1.2.1 Polybius (2007-11-03 09:23) .......................... 12 1.2.2 Cicero and Natural Rights (2007-11-05 14:30) . 12 1.2.3 Pliny and Trajan (2007-11-20 16:30) ...................... 12 1.2.4 Variety is the Spice of Life! (2007-11-21 14:27) . 12 1.2.5 Marcus - or Not (2007-11-25 06:18) ...................... 13 1.2.6 Semitic? (2007-11-26 20:29) .......................... 13 1.2.7 The Empire’s Last Chance (2007-11-26 20:45) . 14 1.3 December . 15 1.3.1 The Effect of the Crusades on European Civilization (2007-12-04 12:21) 15 1.3.2 The Plague (2007-12-04 14:25) ......................... 15 2 2008 17 2.1 January . 17 2.1.1 The Greatest Goth (2008-01-06 19:39) .................... 17 2.1.2 Just Justinian (2008-01-06 19:59) ........................ 17 2.2 February . 18 2.2.1 How Faith Contributes to Society (2008-02-05 09:46) . 18 2.3 March . 18 2.3.1 Adam Smith - Then and Now (2008-03-03 20:04) . 18 2.3.2 William Blake and the Doors (2008-03-27 08:50) . 19 2.3.3 It Must Be True - I Saw It On The History Channel! (2008-03-27 09:33) . -

Ancient Egypt and Kush (4500 BC–AD 400)

FLORIDA . The Story Continues CHAPTER 4, Ancient Egypt and Kush (4500 BC–AD 400) PEOPLE 2500 BC–AD 100: The Deptford culture emerges in the northern and northwestern regions of Florida. Regional cultures developed as Florida’s people became more settled. Styles of pottery were an important regional di erence. Archaeologists use pottery to organize archaeological sites into cultural groups. e Deptford culture developed in what is now North and Northwest Florida. e culture’s pottery was charac- terized by a checked design stamped into coiled clay. Most of the people in the northwestern region lived along the coast near salt marshes and streams. e people in the northern region lived along rivers and streams. ey all shed and hunted for food. Around 100 BC the Deptford culture began burying their dead in sand mounds. e dead were buried with special items such as copper panpipes, ear spools, and decorative pottery. Copper is not native to Florida. is leads archaeologists to believe that the Deptford people engaged in trade with other cultures of the Southeast. PEOPLE c. 1000 BC: The Belle Glades culture emerges around Lake Okeechobee. e Belle Glades culture devel- oped in the grasslands around the Kissimmee River basin and Florida. .The Story Continues Lake Okeechobee in southern Florida. By about 500 BC the people were constructing mounds, circular ditches, canals, and other earthworks. Archaeologists believe that many of the See Chapter 1 earthworks were constructed to control seasonal ooding in the increasingly wet environment. e people appear to have grown corn as early as 400 BC, but the practice stopped around Photo credits: AD 500, most likely because the land became too wet. -

Chapter 8 Ancient Greece

Chapter 8 Ancient Greece Section 1 Geography And The Early Greeks Geography Shapes Greek Civilization • Greece is a peninsula. • Its is mountainous & rocky. • There are a few valley and flat coastal plains for farming. Mountains and Settlements • Greek communities saw themselves as separate countries. • Most communities were along the coast. • Those that were inland were separated by the mountains. Seas & Ships • The early Greeks turned to the seas to for food & trading. • The Greeks were skilled shipbuilders & sailors. • They traveled to places such as Egypt & present-day Turkey. Trading Cultures Develop • The two earliest Greek cultures that developed were the Minoans and Mycenaeans. • The Minoans built their society on the island of Crete. • The Mycenaeans built theirs on the Greek mainland. The Minoans • Since the Minoans lived on an island, they spent much of their time at sea. • It’s location was perfect for traders, but it was also dangerous. The Minoans • In the 1600s BC, a huge volcano erupted just south of Crete. • It caused a giant wave that flooded much of the island. The Minoans • The eruption threw up huge clouds of ash, ruining crops and burying cities. • Historians think this is what led to the end of their civilization. The Mycenaeans • They lived in the place that is now Greece. • Historians do not consider the Minoans Greek because they did not speak the Greek language. • Historians consider the Mycenaeans to be the first Greek people. The Mycenaeans • The Mycenaeans built fortresses all over the Greek mainland. • The Minoan civilization declined which allowed the Mycenaeans to take over Crete. -

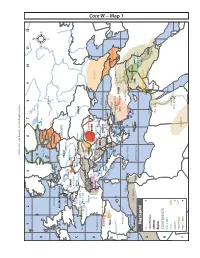

Core W—Map 1

©2013 by Sonlight Curriculum, Ltd. All rights reserved. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Baltic Shore St. Petersburg (Leningrad) A Neva River Baltic Sea ESTONIA LATVIA Moscow DENMARK Baltic States Gilleleje Helsingr North Sea Kolding Copenhagen LITHUANIA B HOLLAND/NETHERLANDS Gdynia BRITAIN EUROPE Witte Verden POLAND Alkmaar West Berlin Warsaw Amsterdam Amersfoort Brunswick GERMANY Oder River Calais Saxony BELGIUM Frankfurt Cambrai Prague Krakow C Crécy Mainz Elbe River Worms Rhine River Carpathian Mountains UKRAINE Paris Marne Brno Brest Normandy Seine River Vienna Hungarian Plain Tisza River Orléans Basel Oberammergau Swiss Alps Budapest Cluj Chalon Faido HUNGARY Transylvania W— Core Geneva Mendrisio Como Trieste Zagreb ROMANIA D Venice Crimea Lombardy Belgrade Danube River Caucasus Burtigala(Bordeaux) Genoa Florence Ravenna Alps Bucharest Sarajevo Rubicon River San Marino SERBIA Black Sea Pyrenees Mountains Tiber River BULGARIA Navarre Soa Stara Zagora Elba ITALY MONTENEGRO Plovdiv Rhodope Mountains Rome MACEDONIA SPAIN Aragon Adriatic Sea Tirana Map 1 E Pompeii ALBANIA Serrai Philippi Constantinople Salerno Brindisi Transcaucasia Thebe Hellespont (Dardanelles) Mount Ararat GREECE Bay of Salamis Scyros TURKEY Thermopylae Lydia Phrygia Assyria Córdoba (Cordova) Ithaca Athens SICILY Çatal Hüyük Hippo Zama Carthage Siracusa (Syracuse) Sparta Nineveh F Cadiz Pillars of Heracles Knossos Lycia Mesopotamia Strait of Gibraltar Atlas Mountains Tigris River TUNISIA Mediterranean Sea Crete SYRIA Euphrates River Map Legend Byblos Northern Kingdom Baghdad Cities ISRAEL G Rosetta Southern Kingdom CHALDEA States/Provinces Alexandria Judea Ur COUNTRIES Memphis Regions H CONTINENTS Bodies of Water Red Sea Deserts Abydos Thebes Mountain Hermonthis Mountain Range Libyan Desert I Points of Interest ©2013 by Sonlight Curriculum, Ltd. -

The Development of the Notion of Libraries in the Ancient World With

~ ' I' UNIVERSI1Y OF CAPE TOWN FACUL1Y OF EDUCATION The development of the notion of libraries in the ancient world with special reference to the Middle East, Greece, the Roman Republic andTown the Royal Alexandrian Library. Cape A dissertation presented in fulfilment of theof requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy in Librarianship. Universityby Niels Ruppelt SEPTEMBER 1993 1' , :,·i~· ~~J~~?f) nit•·~;, ~ .• ~.,. +.·. • ·. , • ., ;i:~::~;.. :.; ,r, \Vhr·.;~:! ~ 1 ' • ., .. • , • 1 t • 1 <~1r tt1t11:1r. • '),,rt · t 'l·} • 4 I ·--~---.-. __ _... ....... -. ,. .... .._ .... .....-~ The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town The financial assistance of the Centre for Science Development towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed in this publication, or conclusions arrived at, are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the Centre for Science Development. ABSTRACT The Royal Alexandrian Library (RAL) is considered by modern scholarship to represent the epitome of the development of ancient librarianship. Its extensive holdings imply the application of modern organizational procedures such as collection development, information retrieval and promotion of use - terms identifiable as elements embodied in the conceptual framework of librarianship (for the purposes of this study the latter two concepts - information retrieval and promotion of use - are combined into the simplified general concept of "collection accessibility"). -

Historical Synopsis of University Collections and Museums, with Reference to Precursors and Significant Events193

University museums and collections in Europe Volume 2 – Appendices [M. C. Lourenço, 2005. Between two worlds: the distinct nature and contemporary significance of university museums and collections in Europe. PhD dissertation, Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers, Paris] Appendix A8: Historical synopsis of university collections and museums, with reference to precursors and significant events193 Early ‘teaching collections’: - c. 3000 BC: Introduction of the concept of State archives by the Sumerians (Lewis 1984). - c. 2800 BC: Hortus medicus of Emperor Shen Nung of China. The Sheng Nung Peng Tsao is considered the earliest materia medica. - 2nd millennium BC: Teaching ‘collections’ of the Larsa Schools, Mesopotamia (Woolley & Moorey 1982, Lewis 1984, Boylan 1999). - c. 1500 BC: Garden of the King of Thebes, Egypt (Foster 1999). - 1500s BC: Garden of King Thutmose III (reigned 1520-1504 BC), Temple of Amun, Karnak, Egypt; planted by Nekht (Foster 1999). - 1400s BC (dated 1460 BC by Foster 1999): Menagerie of Queen Hatshepsut (reigned c. 1473-1458 BC), Thebes, Egypt, included monkeys, leopards, wild cattle, giraffe, and birds (Alexander 1979: 110). - 9th century BC: Ashurnasirpal II of Assyria collected plants and seeds from abroad for home growing (Foster 1999). - 700 BC: The beginning of animal menageries in Greece. - 530 BC: Sumerian ‘school museum’, with historic artefacts and a ‘museum label’ in clay dating from 2000 BC, in Ur, Mesopotamia. The school was established by En-nigaldi- Nanna, daughter of Nabonidus, the last king of Babylon (Woolley & Moorey 1982, Lewis 1984, Boylan 1999). - 4th century BC: Botanical Garden of Aristotle’s Lyceum in Athens. The Lyceum also had a Menagerie, provided by Aristotle’s former pupil Alexander the Great (Whitehead 1970). -

History Helpers 2014-15 Name______Block______

History Helpers 2014-15 Name______________________________________ Block______ Pre-civilization (Pre-history) Before written records, hunter-gatherer communities Civilizations (History) People could stay in one place, written records were kept Used simple tools to construct shelter, hunt and make clothes Hunter-gatherer Adapted to their environment Traveled in search of food – followed animals as they migrated Communities Used stone tools and used art to express themselves Technology Used discoveries from the Old Stone Age such as fire Used language to communicate, men and women had certain roles Cultural and Social Characteristics Climate changes or migrating animals sometimes caused people to migrate. People moved between Asia and North America during the ice ages using a land bridge. Migratory patterns – moved from place to place to find food, water and shelter People shared ideas with other people as they moved. Humans had been nomads (moved from place to place) but settled into the cradles of civilization (lived in communities). People began living in villages instead of moving place to place. Allowed people to stay in one place and raise their food – They sometimes had a surplus of food which brought Agriculture population growth and labor specialization (each worker specializes a certain job – farmers, traders, craftspeople). Irrigation Allowed people to water their crops and not depend on rain – They used dams and canals. Domestication Allowed people to raise animals and plants for food and other needs – They didn’t have to hunt and gather. Agricultural Techniques Development of plows, water wheels, using animals to help with work (such as pulling plows) Government Government was needed as people began living in larger communities All early civilizations began along river systems because the rivers provided important natural resources such as water, food and fertile soil. -

Ancient Egypt and Kush

CHAPTER 4 4500 BC–AD 400 Ancient Egypt and Kush Essential Question How was the success of the Egyptian civilization tied to the Nile River? What You Will Learn... In this chapter you will learn about two great civiliza- tions that developed along the Nile River—Egypt and Kush. SECTION 1: Geography and Ancient Egypt . 86 The Big Idea The water, fertile soils, and protected setting of the Nile Valley allowed a great civilization to arise in Egypt around 3200 BC. SECTION 2: The Old Kingdom . 90 The Big Idea Egyptian government and religion were closely connected during the Old Kingdom. SECTION 3: The Middle and New Kingdoms . 96 The Big Idea During the Middle and New Kingdoms, order and greatness were restored in Egypt. SECTION 4: Egyptian Achievements . 102 The Big Idea The Egyptians made lasting achievements in writing, archi- tecture, and art. SECTION 5: Ancient Kush . 107 The Big Idea The kingdom of Kush, which arose south of Egypt in a land called Nubia, developed an advanced civilization with a large trading network. c. 4500 BC Agricultural FOCUS ON WRITING CHAPTER communities EVENTS develop in Egypt. Riddles In ancient times, according to legend, a sphinx—an imaginary creature like the one whose sculpture is found in Egypt—demanded the 4000 BC answer to a riddle. People died if they couldn’t answer the riddle WORLD correctly. After you read this chapter, you will write two riddles. The EVENTS answer to one of your riddles will be “Egypt.” The answer to your other riddle will be “Kush.” 82 CHAPTER 4 6-8_SNLAESE485805_C04O.indd 82 6/28/10 3:14:34 PM This photo shows The Egyptian an ancient temple of Empire Is Born Ramses II, one of Egypt’s most powerful rulers. -

Page 1 1 T H E M I D D L E a N D N E W K I N G D O M S ANCIENT

10/25/2016 1 THE MIDDLE AND NEW KINGDOMS ANCIENT EGYPT 2 THE MIDDLE KINGDOM Wealth and power of pharaohs declined at the end of Old Kingdom By about 2200 BC the Old Kingdom had fallen Egypt was in chaos- economically, agriculturally, and with no set ruler In 2050 BC Pharaoh Mentuhotep II defeated his rivals and united Egypt once again Mentuhotep’s rule began the Middle Kingdom A period of order and stability that lasted until about 1750 BC. 3 THE MIDDLE KINGDOM The Middle Kingdom also experienced internal disorder. In the mid-1700s BC the Hyksos invaded and conquered Lower Egypt They used horses, chariots, and other advanced weapons. The Hyksos ruled Lower Egypt for 200 years. In the mid-1500s BC, Ahmose of Thebes led the Egyptians taking back control. Once the Hyksos were gone, Ahmose declared himself king of all of Egypt. 4 THE NEW KINGDOM Ahmose’s rise to power marked Egypt’s 18th Dynasty (a series of rulers from the same family) This also brought about the New Kingdom The period during which Egypt reached the height of its power and glory. Because of what happened during the Middle Kingdom, the Egyptians built up their military and strengthened its boarders. They conquered regions that created an Empire that extended from the Euphrates River to southern Nubia 5 QUEEN HATSHEPSUT Egypt wanted to grow its kingdom so they began to trade. Profitable trade routes, or paths followed by traders, developed Queen Hatshepsut worked to increase Egyptian trade. She expanded trade to the south with kingdom of Punt on the Red Sea and to the north with the people of Asia Minor and Greece She and later pharaohs used the wealth the earned to support the arts and architecture. -

World History

Interactive Reader and Study Guide Holt Social Studies World History 5394_MSH_IntActReaderSG_FM.indd i 3/22/05 6:32:17 PM Copyright © by Holt, Rinehart and Winston All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any informa- tion storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Teachers using HOLT SOCIAL STUDIES: WORLD HISTORY may photocopy complete pages in sufficient quantities for classroom use only and not for resale. HOLT and the “Owl Design” are trademarks licensed to Holt, Rinehart and Winston, registered in the United States of America and/or other jurisdictions. Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-03-042314-7 2 3 4 5 6 7 082 08 07 06 05 55671_MSH_IntActReaderSG_FM.indd671_MSH_IntActReaderSG_FM.indd iiii 66/29/05/29/05 66:33:51:33:51 PMPM Contents Interactive Reader and Study Guide Chapter 5 Chapter Opener with Graphic Organizer . 33 Chapter 1 Sec 5.1 . 34 Chapter Opener with Graphic Organizer . 1 Sec 5.1 . 35 Sec 1.1 . 2 Sec 5.2 . 36 Sec 1.1 . 3 Sec 5.2 . 37 Sec 1.2 . 4 Sec 5.3 . 38 Sec 1.2 . 5 Sec 5.3 . 39 Chapter 2 Sec 5.4 . 40 Chapter Opener with Graphic Organizer . 6 Sec 5.4 . 41 Sec 2.1 . 7 Sec 5.5 . 42 Sec 2.1 . 8 Sec 5.5 . 43 Sec 2.2 . 9 Chapter 6 Sec 2.2 . 10 Chapter Opener with Graphic Organizer .