Yours, Mine & Ours: What Ancient Egyptian Possessives Can Tell Us

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The for Ma Tion of the Self. Nietz Sche and Com Plex

The Forma tion of the Self. Nietz sche and Complex ity Paul Cilliers,1 Tanya de Villiers and Vasti Roodt De part ment of Phi los o phy, Uni ver sity of Stellenbosch, Pri vate Bag X1, Matieland, 7602, South Af rica Ab stract: The purpose of this arti cle is to exam ine the rela ti on ship be tween the form a- tion of the self and the worldly ho rizon within which this self achieves its meaning. Our in quiry takes place from two per spec tives: the first de rived from the Nietzschean analy sis of how one becom es what one is; the other from current devel op m ents in com plexit y theory. This two-angled approach opens up differ ent, yet relat ed dim ensions of a non-essentialist un dersta nd - ing of the self that is nonethe les s nei ther arbi tra ry nor de ter minis ti c. Indeed, at the meet ing point of these two per spec tives on the self lies a concep ti on of a dynam ic, worldly self, whose iden tity is bound up with its ap pearance in a world shared with oth ers. Af ter exam ining this argu ment from the respec tive view points offered by Nietzsche and com plexit y theory, the arti cle con- cludes with a con sid er ation of some of the po lit i cal and eth i cal impli ca tions of repre sent ing our situatedness within a shared hum an dom ain as a con di- tion for self-formation. -

Are You Eligible for the Senior Citizen Homeowner

Please read but do not submit with your application Homeowner Tax Benefits Initial Application Instructions for Tax Year 2018/19 Please note: If the property has a life estate, only the individual retaining the life estate can apply. If the property is held in a trust, only the qualifying beneficiary/trustee can apply. Are you eligible for the Senior Citizen Homeowner Exemption (SCHE)? • Will all owners be 65 years of age or older by December 31, 2018? n Yes n No OR • If you own your property with either a spouse or sibling, will at least one of you be 65 years of age or older by December 31, 2018? • Will you have owned this property for at least 12 consecutive months prior n Yes n No to the date of filing this application? • Is the property the primary residence for ALL senior owners and their spouses? n Yes n No (All owners must reside on the property unless they are legally separated, divorced, abandoned or residing in a health care facility.*) *If an owner is residing in a health care facility, please submit documentation including total cost of care at the facility. • Is the Total Combined Income (TCI) for all owners and spouses $37,399 or less, n Yes n No regardless of where they live? (The income of a spouse may be excluded if he or she is absent from the residence due to divorce, legal separation or abandonment.) If you have answered NO to any of these questions, you MAY NOT be eligible for the Senior Citizen Homeowner Exemption. -

Person and Number in Pronouns: a Feature-Geometric Analysis

PERSON AND NUMBER IN PRONOUNS: A FEATURE-GEOMETRIC ANALYSIS HEIDI HARLEY ELIZABETH RITTER University of Arizona University of Calgary The set of person and number features necessary to characterize the pronominal paradigms of the world’s languages is highly constrained, and their interaction is demonstrably systematic. We develop a geometric representation of morphosyntactic features which provides a principled explanation for the observed restrictions on these paradigms. The organization of this geometry represents the grammaticalization of fundamental cognitive categories, such as reference, plurality, and taxonomy. We motivate the geometry through the analysis of pronoun paradigms in a broad range of genetically distinct languages.* INTRODUCTION. It is generally accepted that syntactic and phonological representa- tions are formal in nature and highly structured. Morphology, however, is often seen as a gray area in which amorphous bundles of features connect phonology with syntax via a series of ad hoc correspondence rules. Yet it is clear from the pronoun and agreement paradigms of the world’s languages that Universal Grammar provides a highly constrained set of morphological features, and moreover that these features are systematically and hierarchically organized.1 In this article we develop a structured representation of person and number features intended to predict the range and types of interactions among them. More specifically, we will motivate the claims in 1. (1) Claims a. The language faculty represents pronominal elements with a geometry of morphological features. b. The organization of this geometry is constrained and motivated by con- ceptual considerations. c. Crosslinguistic variation and paradigm-internal gaps and syncretisms are constrained by the hierarchical organization of features in the universal geometry. -

The Aristocratic Warlike Ethos of Indo-Europeans and the Primordial Origins of Western Civilization—Part Two Ricardo Duchesne [email protected]

Comparative Civilizations Review Volume 61 Article 3 Number 61 Fall 2009 10-1-2009 The Aristocratic Warlike Ethos of Indo-Europeans and the Primordial Origins of Western Civilization—Part Two Ricardo Duchesne [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr Recommended Citation Duchesne, Ricardo (2009) "The Aristocratic Warlike Ethos of Indo-Europeans and the Primordial Origins of Western Civilization—Part Two," Comparative Civilizations Review: Vol. 61 : No. 61 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr/vol61/iss61/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the All Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Comparative Civilizations Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Duchesne: The Aristocratic Warlike Ethos of Indo-Europeans and the Primordi The Aristocratic Warlike Ethos of Indo-Europeans and the Primordial Origins of Western Civilization—Part Two1 Ricardo Duchesne [email protected] Western civilization has been the single most war-ridden, war- dominated, and militaristic civilization in all human history. Robert Nisbet [Mycenaean] society was not the society of a sacred city, but that of a military aristocracy. It is the heroic society of the Homeric epic, and in Homer's world there is no room for citizen or priest or merchant, but only for the knight and his retainers, for the nobles and the Zeus born kings, 'the sackers of cities.' Christopher Dawson [T]he Greek knows the artist only in personal struggle... What, for example, is of particular importance in Plato's dialogues is mostly the result of a contest with the art of orators, the Sophists, the dramatists of his time, invented for the purpose of his finally being able to say: 'Look: I, too, can do what my great rivals can do; yes, I can do it better than them. -

ETYMOLOGY. the Coptic Language Comprises an Autochthonous

(CE:A118a-A124b) ETYMOLOGY. The Coptic language comprises an autochthonous vocabulary (see VOCABULARY OF EGYPTIAN ORIGIN and VOCABULARY OF SEMITIC ORIGIN) with an overlay of several heterogeneous strata (see VOCABULARY, COPTO-GREEK and VOCABULARY, COPTO-ARABIC). As a rule, etymologic research in Coptology is limited to the autochthonous vocabulary. Etymology (from Greek etymos, true, and logos, word) is the account of the origin, the meaning, and the phonetics of a word over the course of time and the comparison of it with cognate or similar terms. In Coptic the basic vocabulary, as well as the morphology of the language, is of Egyptian origin. Egyptian shares many words and all its morphology (grammatical forms) with the Semitic languages. Egyptian is transcribed with an alphabet of twenty-four letters in the following order: 3, „ , ‘, w, b, p, f, m, n, r, h, , , h, z, s, , (sometimes transcribed q), k, g, t, t, d, d. All these letters represent consonants. The sign 3 is the glottal stop heard at the commencement of German words beginning with a vowel (die Oper) or Hebrew aleph; „ is y in “yes,” but sometimes pronounced like aleph; ‘ is called ‘ayin, as in Hebrew, the emphatic correspondent to aleph (cf. Arabic ‘Abdallah); h is the English h; is an emphatic h, as in Arabic Mu ammad; is the Scotch ch in loch; h is like German ch in ich (between and ), and nearly like English h in human; is English sh in “ship”; t is ch in English “child”; and d is English j in ‘joke.” The group „„ is pronounced y. -

Nonconcatenative Morphology in Coptic

UC Santa Cruz Phonology at Santa Cruz, Volume 7 Title Nonconcatenative Morphology in Coptic Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0765s94q Author Kramer, Ruth Publication Date 2018-04-10 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Nonconcatenative Morphology in Coptic ∗∗∗ Ruth Kramer 1. Introduction One of the most distinctive features of many Afroasiatic languages is nonconcatenative morphology. Instead of attaching an affix directly before or after a root, languages like Modern Hebrew interleave an affix within the segments of a root. An example is in (1). (1) Modern Hebrew gadal ‘he grew’ gidel ‘he raised’ gudal ‘he was raised’ In the mini-paradigm in (1), the discontinuous affixes /a a/, /i e/, and /u a/ are systematically interleaved between the root consonants /g d l/ to indicate perfective aspect, causation and voice, respectively. The consonantal root /g d l/ ‘big’ never surfaces on its own in the language: it must be inflected with some vocalic affix. Additional Afroasiatic languages with nonconcatenative morphology include other Semitic languages like Arabic (McCarthy 1979, 1981; McCarthy and Prince 1990), many Ethiopian Semitic languages (Rose 1997, 2003), and Modern Aramaic (Hoberman 1989), as well as non-Semitic languages like Berber (Dell and Elmedlaoui 1992, Idrissi 2000) and Egyptian (also known as Ancient Egyptian, the autochthonous language of Egypt; Gardiner 1957, Reintges 1994). The nonconcatenative morphology of Afroasiatic languages has come to be known as root and pattern -

The Interesting Transition of Third-Person Pronouns from the Old English to the Present Forms

The Interesting Transition of Third-Person Pronouns from the Old English to the Present Forms 三人称代名詞の興味深い形態上の変遷 SATO Tetsuzo* 摘 要 古英語期の三人称代名詞の語頭は, 性, 格, 数に関わらず全てh であった. 現代英語のそれと比較すると, 中性単 数のh は消失し, 単数女性主格はsh に代わり, 複数はth に代わったことがわかる. 古英語期に整然と使用されてい たものが, 中英語期, 現代英語期への時代の変遷と共に変化していった過程は興味深いものがある. またその変遷 過程の一時期の古形と新形が混在している状況下で, 絶妙な意味合いの違いをそれぞれの形に付与して, 筋の展 開に奥行きの深さを与えている作品も生まれた. 本論では, 三人称代名詞における語頭の変遷過程を説明し, その 後で, 中英語期の中盤に書かれたHavelok the Dane (デーン人ハヴェロック) に現れる三人称単数女性主格形と三 人称複数主格形をつぶさに観察することで, その妙技の一端を確認したい. Keyword Old English forms, third-person pronouns, Havelok the Dane CONTENTS Introduction Chapter I A General View of the Changing Forms of the Third-Person Pronouns Chapter II Sentences and Phrases Containing “She” and “They” in Havelok the Dane Chapter III Consideration of the Lists Conclusion Notes References Introduction Due to this state of linguistic confusion, in the districts where these dialects were spoken there may have been All the third-person pronouns in Old English (OE) a strong motive for using sh-forms as the singular began with an initial letter h. As a result of the phonetic feminine nominative and th-forms as the plural development of various dialects between late OE and nominative. With regard to the former group, the early Middle English (ME), the third-person pronoun Peterborough Chronicle for the year 1140 provides our nominatives with the initial h, except the singular neuter first evidence of the form with the initial /∫/-sound, scæ, 1) hit (which lost its initial h between the 12th and 15th in ME. In Havelok the Dane, written in the North East centuries in Standard English), became almost or wholly Midland dialect about 150 years later than the Chronicle, identical in form. the more developed forms of scho, * [email protected] -55- sho, sche, and she appeared. -

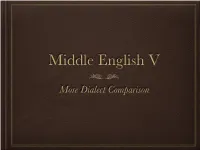

More Dialect Comparison Two Catechisms

Middle English V More Dialect Comparison Two Catechisms Text 1 is from the York Lay Folk's Catcechism (1357), written by John de Thoresby (Archbishop of York). This is in northern dialect. Text 2 is written "a little later" by John Wyclif, who worked a long time in Oxford and Leicestershire. This is in West Midlands dialect. 2 Catechisms 1 - North 2 - Midlands This er the sex thinges that I have These be þe sexe thyngys þat y haue spoken of, spokyn of þat þe law of holy chirche lys most That the lawe of halikirk lies mast in yn That ye er al halden to knawe and to þat þey be holde to know and to kun, kunne; If ye sal knawe god almighten and yf þey shal knowe god almyȝty and cum un to his blisse: come to þe blysse of heuyn. And for to gif yhou better will for to And for to ȝeue ȝow þe better wyl kun tham, for to cunne ham. Our fadir the ercebisshop grauntes Our Fadyr þe archiepischop grauntys of his grace of hys grace Fourti daies of pardon til al that forty dayes of Pardoun. to alle þat kunnes tham, cunne hem Or dos their gode diligence for to and rehercys hem .... kun tham ..... 2 Catychisms 1 - Northern 2 - Midlands For if ye kunnandly knaw this ilk For yf ȝe cunnyngly knowe þese sex thinges sexe thyngys; Thurgh thaim sal ye kun knawe þorwȝ hem ȝe schull knowe god god almighten, almyȝty. Wham, als saint Iohn saies in his And as seynt Ion seyþ in hys gospel. -

Reformed Egyptian

Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011 Volume 19 Number 1 Article 7 2007 Reformed Egyptian William J. Hamblin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Hamblin, William J. (2007) "Reformed Egyptian," Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011: Vol. 19 : No. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr/vol19/iss1/7 This Book of Mormon is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011 by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title Reformed Egyptian Author(s) William J. Hamblin Reference FARMS Review 19/1 (2007): 31–35. ISSN 1550-3194 (print), 2156-8049 (online) Abstract This article discusses the term reformed Egyptian as used in the Book of Mormon. Many critics claim that reformed Egyptian does not exist; however, languages and writing systems inevitably change over time, making the Nephites’ language a reformed version of Egyptian. Reformed Egyptian William J. Hamblin What Is “Reformed Egyptian”? ritics of the Book of Mormon maintain that there is no language Cknown as “reformed Egyptian.” Those who raise this objec- tion seem to be operating under the false impression that reformed Egyptian is used in the Book of Mormon as a proper name. In fact, the word reformed is used in the Book of Mormon in this context as an adjective, meaning “altered, modified, or changed.” This is made clear by Mormon, who tells us that “the characters which are called among us the reformed Egyptian, [were] handed down and altered by us” and that “none other people knoweth our language” (Mormon 9:32, 34). -

Ancient Egypt: Symbols of the Pharaoh

Ancient Egypt: Symbols of the pharaoh Colossal bust of Ramesses II Thebes, Egypt 1250 BC Visit resource for teachers Key Stage 2 Ancient Egypt: Symbols of the pharaoh Contents Before your visit Background information Resources Gallery information Preliminary activities During your visit Gallery activities: introduction for teachers Gallery activities: briefings for adult helpers Gallery activity: Symbol detective Gallery activity: Sculpture study Gallery activity: Mighty Ramesses After your visit Follow-up activities Ancient Egypt: Symbols of the pharaoh Before your visit Ancient Egypt: Symbols of the pharaoh Before your visit Background information The ancient Egyptians used writing to communicate information about a person shown on a sculpture or relief. They called their writing ‘divine word’ because they believed that Thoth, god of wisdom, had taught them how to write. Our word hieroglyphs derives from a phrase meaning ‘sacred carvings’ used by the ancient Greek visitors to Egypt to describe the symbols that they saw on tomb and temple walls. The number of hieroglyphic signs gradually grew to over 7000 in total, though not all of them were used on a regular basis. The hieroglyphs were chosen from a wide variety of observed images, for example, people, birds, trees, or buildings. Some represent the sounds of the ancient Egyptian language, but consonants only. No vowels were written out. Also, it was not an alphabetic system, since one sign could represent a combination of two or more consonants like the gaming-board hieroglyph which stands for the consonants mn. Egyptologists make the sounds pronounceable by putting an e between the consonants, so mn is read as men. -

The Arabic Language: a Latin of Modernity? Tomasz Kamusella University of St Andrews

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository Journal of Nationalism, Memory & Language Politics Volume 11 Issue 2 DOI 10.1515/jnmlp-2017-0006 The Arabic Language: A Latin of Modernity? Tomasz Kamusella University of St Andrews Abstract Standard Arabic is directly derived from the language of the Quran. The Ara- bic language of the holy book of Islam is seen as the prescriptive benchmark of correctness for the use and standardization of Arabic. As such, this standard language is removed from the vernaculars over a millennium years, which Arabic-speakers employ nowadays in everyday life. Furthermore, standard Arabic is used for written purposes but very rarely spoken, which implies that there are no native speakers of this language. As a result, no speech com- munity of standard Arabic exists. Depending on the region or state, Arabs (understood here as Arabic speakers) belong to over 20 different vernacular speech communities centered around Arabic dialects. This feature is unique among the so-called “large languages” of the modern world. However, from a historical perspective, it can be likened to the functioning of Latin as the sole (written) language in Western Europe until the Reformation and in Central Europe until the mid-19th century. After the seventh to ninth century, there was no Latin-speaking community, while in day-to-day life, people who em- ployed Latin for written use spoke vernaculars. Afterward these vernaculars replaced Latin in written use also, so that now each recognized European lan- guage corresponds to a speech community. -

Dialectical Variation of the Egyptian-Coptic Language in the Course of Its Four Millennia of Attested History

Helmut Satzinger Dialectical Variation of the Egyptian-Coptic Language in the Course of Its Four Millennia of Attested History Abstract A language with a long documented history may be expected to show a great deal of dialectal diversity. For Egyptian-Coptic there are particular conditions. Except for the Delta, the country is one-dimensional, a feature that may make the distribution of dialectal differences simpler than in a country with a normal areal extension. Another specific feature is that all Egyptian idioms that precede Coptic are transmitted without the vowels, thereby obscuring all vocalic differences (which play such a great role in Coptic dialect variation). However, recent research has revealed that in the earliest stages of Egyptian language history there was a drastic dialectal gap. The feature best visible is the phonetic value and the etymology of graphemesˁ ayin and ȝ. hen Herodotus said that Egypt is a gift of the Nile, he was speaking of Lower Egypt, of the Delta: this wholeW area, with a north–south extension of ca. 170 km (in a bee-line) and an east–west extension of ca. 260 km, owes its existence to all the soil that the river Nile has brought down from the Sudan in the course of a long time-span. However, most people think that he wanted to say that Egypt (as we intend it), from the Tropic of Cancer to the coast of the Mediterranean Sea, would not exist without the waters of the Nile, as there would be nothing but desert. Egypt is bipartite: on the one hand, a small country like others, of triangular shape; on the other, the two long and narrow shores of a river that crosses an endless desert.