=Ë*F7"Lt-.,., ..Re, .Ê'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“The Touch of Cold Philosophy”

Edinburgh Research Explorer The Fragmentation of Renaissance Occultism and the Decline of Magic Citation for published version: Henry, J 2008, 'The Fragmentation of Renaissance Occultism and the Decline of Magic', History of Science, vol. 46, no. Part 1, No 151, pp. 1-48. <http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/shp/histsci/2008/00000046/00000001/art00001> Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: History of Science Publisher Rights Statement: With permission © Henry, J. (2008). The Fragmentation of Renaissance Occultism and the Decline of Magic. History of Science, 46(Part 1, No 151), 1-48 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 23. Sep. 2021 The Fragmentation of Renaissance Occultism and the Decline of Magic* [History of Science, 46 (2008), pp. 1-48.] The touch of cold philosophy? At a Christmas dinner party in 1817 an admittedly drunken -

General Index

General Index Italic page numbers refer to illustrations. Authors are listed in ical Index. Manuscripts, maps, and charts are usually listed by this index only when their ideas or works are discussed; full title and author; occasionally they are listed under the city and listings of works as cited in this volume are in the Bibliograph- institution in which they are held. CAbbas I, Shah, 47, 63, 65, 67, 409 on South Asian world maps, 393 and Kacba, 191 "Jahangir Embracing Shah (Abbas" Abywn (Abiyun) al-Batriq (Apion the in Kitab-i balJriye, 232-33, 278-79 (painting), 408, 410, 515 Patriarch), 26 in Kitab ~urat ai-arc!, 169 cAbd ai-Karim al-Mi~ri, 54, 65 Accuracy in Nuzhat al-mushtaq, 169 cAbd al-Rabman Efendi, 68 of Arabic measurements of length of on Piri Re)is's world map, 270, 271 cAbd al-Rabman ibn Burhan al-Maw~ili, 54 degree, 181 in Ptolemy's Geography, 169 cAbdolazlz ibn CAbdolgani el-Erzincani, 225 of Bharat Kala Bhavan globe, 397 al-Qazwlni's world maps, 144 Abdur Rahim, map by, 411, 412, 413 of al-BlrunI's calculation of Ghazna's on South Asian world maps, 393, 394, 400 Abraham ben Meir ibn Ezra, 60 longitude, 188 in view of world landmass as bird, 90-91 Abu, Mount, Rajasthan of al-BlrunI's celestial mapping, 37 in Walters Deniz atlast, pl.23 on Jain triptych, 460 of globes in paintings, 409 n.36 Agapius (Mabbub) religious map of, 482-83 of al-Idrisi's sectional maps, 163 Kitab al- ~nwan, 17 Abo al-cAbbas Abmad ibn Abi cAbdallah of Islamic celestial globes, 46-47 Agnese, Battista, 279, 280, 282, 282-83 Mu\:lammad of Kitab-i ba/Jriye, 231, 233 Agnicayana, 308-9, 309 Kitab al-durar wa-al-yawaqft fi 11m of map of north-central India, 421, 422 Agra, 378 n.145, 403, 436, 448, 476-77 al-ra~d wa-al-mawaqft (Book of of maps in Gentil's atlas of Mughal Agrawala, V. -

Visio-MERCATOR ENG2.Vsd

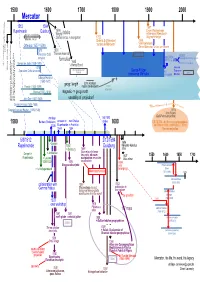

1500 1600 1700 1800 1900 2000 Mercator 1512 1594 1897 Rupelmonde Duisburg 1599 tables Lt-gen Wauwermans Italian composite Wright tables article about Mercator in Certain erros in navigation 1752 Biographie belge atlases IATO 1869 middle 15th Century Diderot & d’Alembert “cartes de Mercator” Van Raemdonck Ortelius (1527-1598) Gérard Mercator, sa vie, son oeuvre printing 1570 1600 Theatrum Orbis Thomas Harrriot projection MGRS terrarum 1772 1825 1914 post WWI military grid reference system formulas Johan Lambert Carl Friedrich Gauss Johann Krüger NATO UTM Gerard de Jode (1509-1591) 1645 transverse Mercator transverse Mercator transverse Mercator civil reference system fall of Constantinople Henry Bond 1578 (sphere) (ellipsoid) (ellipsoid) Universal 1492 end of Reconquista Mercatorprojection Transverse Speculum Orbis terrarum formula Gauss-Krüger 1942 grid transverse Mercator developped Mercator Judocus Hondius (1563-1612) + geogr. length John Harrison Plantijn (1520-1589) marine timekeepers use of projection Moretus (1543-1610) magnetic <> geogr north John Dee (1527-1608) useability of projection? 1488 Bartholomeus Dias rounded Cape of Good Hope 1492 Columbus ‘America’ discovered 1498 Vasco da Gama reached India via Africa 1519 – 1522 Magellan around the world Gemma Frisius (1508-1555) 1904 criticism + -- Gaspard van der Heyden (1496-1549) 1974 Arne Peters (Gall-Peters-projection) mariage 5/5/1590 1500 Barbara Shellekens arrested in met Ortelius stroke 1600 CRITICISM - but from non-cartographers - 1536 Rupelmonde in Frankfurt on ethnocentrism, -

Download Full Article in PDF Format

Serpents buveurs d’eau, serpents œnophiles et serpents sanguinaires : les serpents et leurs boissons dans les sources antiques Jean TRINQUIER* ENS Ulm, AOROC-UMR 8546 CNRS-ENS. [email protected] Trinquier J. 2012. Serpents buveurs d’eau, serpents œnophiles et serpents sanguinaires : les serpents et leurs boissons dans les sources antiques. Anthropozoologica 47.1 : 177-221. Les serpents ont-ils soif ? Que boivent-ils ? À ces deux questions, les sources antiques ap- portent des réponses contrastées, qui tantôt valent pour tous les ophidiens, tantôt seule- ment pour certaines espèces. D’un côté, les serpents passaient pour des animaux froids, et on concluait logiquement qu’ils n’avaient pas besoin de beaucoup boire, une déduction confirmée par l’observation de spécimens captifs ; telle était notamment la position d’Aris- tote. D’un autre côté, les serpents venimeux, en particulier les Vipéridés, étaient volontiers MOTS CLÉS mis en rapport avec le chaud et le sec, en raison tant de leur virulence estivale que des effets physiologie composition assoiffants de leur venin ; ils étaient plus facilement que d’autres décrits comme assoiffés, crase ou amateurs de vin, le vin étant lui aussi considéré comme chaud et sec. Un autre serpent toxicologie assoiffé est le python des confins indiens et éthiopiens, censé attaquer les éléphants pour épistémologie légendes les vider de leur sang à la façon d’une sangsue. À travers ces différents cas, la contribution vin étudie la façon dont s’est élaborée dans l’Antiquité, à partir d’un stock disparate de données sang serpents géants légendaires, de représentations mythiques et d’observations attentives, une réflexion sur la vampire crase des différentes espèces d’ophidiens. -

Fortis-Bank-Sa-Nv-2003.Pdf

I. INTRODUCTION 3 II. PROPOSED PROFIT APPROPRIATION FOR THE PERIOD 4 DISTRIBUTION OF AN INTERIM DIVIDEND : REPORT OF THE ACCREDITED STATUTORY AUDITORS 6 III. AUDITORS: SPECIAL BRIEFS 8 IV. ARTICLE 523 OF COMPANY LAW 8 V. NOTES TO THE CONSOLIDATED BALANCE SHEET AND INCOME STATEMENT 9 VI. CONSOLIDATED BALANCE SHEET AND INCOME STATEMENT 15 REPORT OF THE ACCREDITED STATUTORY AUDITORS 83 VII. SHAREHOLDER BASE 85 VIII. MONTHLY HIGH AND LOW FOR FORTIS BANK SHARES ON THE WEEKLY AUCTIONS IN 2003 86 IX. BOARD OF DIRECTORS AND COUNCIL OF ACCREDITED STATUTORY AUDITORS FORTIS BANK 87 X. EXTERNAL POSTS HELD BY DIRECTORS AND EXECUTIVES THAT ARE SUBJECT TO A LEGAL DISCLOSURE REQUIREMENT 89 I. INTRODUCTION This document contains the annual report and the consolidated annual accounts of Fortis Bank as at 31 December 2003. The financial environment in which Fortis Bank operates was influenced in 2003 by an international unstable geopolitical situation combined with less than positive economic conditions and an improving, though still hesitant stock market climate. Despite a persistently challenging international economic environment, both Fortis and Fortis Bank once again succeeded during 2003 in streamlining and expanding operations beyond the domestic Benelux market; this had implications in terms of commercial organisation and operational and support activities. Fortis Bank continues to focus on its customer-first policy, vigorous cost control, efficiency improvement and the effective management of increased financial risks. Initiatives launched in previous years to prepare for the introduction and repercussions of the revision of the Basel Accord of 1988 regarding the capital adequacy standards of banks and the application of IAS/IFRS (International Accounting Standards / International Financial Reporting Standards) were further pursued in 2003; both changes will have a major impact on financial reporting. -

October 2006

OCTOBER 2 0 0 6 �������������� http://www.universetoday.com �������������� TAMMY PLOTNER WITH JEFF BARBOUR 283 SUNDAY, OCTOBER 1 In 1897, the world’s largest refractor (40”) debuted at the University of Chica- go’s Yerkes Observatory. Also today in 1958, NASA was established by an act of Congress. More? In 1962, the 300-foot radio telescope of the National Ra- dio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) went live at Green Bank, West Virginia. It held place as the world’s second largest radio scope until it collapsed in 1988. Tonight let’s visit with an old lunar favorite. Easily seen in binoculars, the hexagonal walled plain of Albategnius ap- pears near the terminator about one-third the way north of the south limb. Look north of Albategnius for even larger and more ancient Hipparchus giving an almost “figure 8” view in binoculars. Between Hipparchus and Albategnius to the east are mid-sized craters Halley and Hind. Note the curious ALBATEGNIUS AND HIPPARCHUS ON THE relationship between impact crater Klein on Albategnius’ southwestern wall and TERMINATOR CREDIT: ROGER WARNER that of crater Horrocks on the northeastern wall of Hipparchus. Now let’s power up and “crater hop”... Just northwest of Hipparchus’ wall are the beginnings of the Sinus Medii area. Look for the deep imprint of Seeliger - named for a Dutch astronomer. Due north of Hipparchus is Rhaeticus, and here’s where things really get interesting. If the terminator has progressed far enough, you might spot tiny Blagg and Bruce to its west, the rough location of the Surveyor 4 and Surveyor 6 landing area. -

De Grote Dooi Zet In

De grote dooi zet in Karen Bies De Eerste Kamer heeft dit voorjaar de klimaatdoelen voor 2050 vastgesteld. Een energietransitie moet, maar welke maatregelen er komen en wie die gaat betalen, is niet duidelijk. ‘We kunnen niet op onze handen blijven zitten,’ zegt poolonderzoeker Maarten Loonen. Hij ziet op Spitsbergen de gletsjers afbrokkelen, de permafrost ontdooien. ‘Heel veel dat niet voorspeld was, is toch gebeurd. Dat maakt mij bang.’ ‘Op Spitsbergen, in een berg die altijd liep smeltwater van de ingang naar de letterlijk een rondje boven mijn hoofd. In bevroren is, zit sinds tien jaar een kamers toe. Het water bevroor en de drie het dorp Ny Ålesund zijn ‘s zomers 180 zadenbank. De zaden van een miljoen kilometer lange gang werd een ijsbaan. wetenschappers uit allerlei landen, die plantenrassen zijn daar in kamers Een ontwerpfout, zou je kunnen zeggen. elk hun eigen terrein onderzoeken. Ik ben ondergebracht. In geval van een grote Maar het laat ook zien dat we nog niet erheen gegaan voor de ganzen, verzamel oorlog of natuurramp zou deze ‘doomsday weten wat ons overkomt. Je probeert iets ook data over het gras, de poolvossen en vault’ het voedsel van de wereld veilig te bedenken dat alle rampen van de wereld de ijsberen. En omdat er zoveel verandert, stellen. Mocht de stroom in de ‘Svalbard overleeft. Nu al is het niet voldoende om doe ik nu ook de Noordse sternen en de Global Seed Vault’ uitvallen, dan duurt de klimaatverandering op Spitsbergen te insecten erbij.’ het 100 jaar eer de berg ontdooid is. De ondervangen.’ ingang zit op 70 meter hoogte. -

California Virtual Book Fair 2021

Bernard Quaritch Ltd 50 items for the 2021 Virtual California Book Fair BERNARD QUARITCH LTD 36 Bedford Row, London, WC1R 4JH tel.: +44 (0)20 7297 4888 fax: +44 (0)20 7297 4866 email: [email protected] web: www.quaritch.com Front cover image from item 20. LALIEU, Paul and Nicolas Joseph BEAUTOUR. P[hiloso]phia particularis Inside cover background from item 8. [CANONS REGULAR OF THE LATERAN]. Regula et constitutiones Canonicorum Regularium Last page images from item 13. [CUSTOMARY LAW]. Rechten, ende costumen van Antwerpen. and item 29. MARKHAM, Cavalarice, or the English Horseman Bankers: Barclays Bank PLC 1 Churchill Place London E14 5HP Sort code: 20-65-90 Account number: 10511722 Swift code: BUKBGB22 Sterling account: IBAN: GB71 BUKB 2065 9010 5117 22 Euro account: IBAN: GB03 BUKB 2065 9045 4470 11 U.S. Dollar account: IBAN: GB19 BUKB 2065 9063 9924 44 VAT number: GB 322 4543 31 ALDROVANDI'S QUADRUPEDS IN FIRST EDITION 1. ALDROVANDI, Ulisse. De quadrupedibus solidipedibus volume integrum … cum indice copiosissimo. Bologna, Vittoria Benacci for Girolamo Tamburini, 1616. [with:] Quadrupedum omnium bisulcorum historia … ucm indice copiosissimo. Bologna, Sebastiano Bonomi for Girolamo Tamburini, 1621. [and:] De quadrupedibus digitatis viviparis libri tres, et de quadrupedibus digitatis oviparis libri duo … cum indice memorabiliumetvariarumlinguarumcopiosissimo. Bologna,NicolaoTebaldiniforMarcoAntonioBernia,1637. 3 vols, folio, pp. 1: [8], 495, [1 (blank)], [30], [2 (colophon, blank)], 2: [11], [1 (blank)], 1040, [12], 3: [8], 492, ‘495-718’ [i.e. 716], [16];eachtitlecopper-engravedbyGiovanniBattistaCoriolano,withwoodcutdevicestocolophons,over200largewoodcutillustrations (12, 77, and 130 respectively), woodcut initials and ornaments; a few leaves lightly foxed and occasional minor stains, a little worming to early leaves vol. -

Index of Articles and Authors for the First Twenty-Four Numbers

Index of Articles and Authors for the first Twenty-four Numbers MARCH 1923 — NOVEMBER 1935 0 THE HYDROGRAPHIC REVIEW The Directing Committee of the I nternational H ydrographic B u r e a u will be pleased to consider articles for insertion in the Hydrographic Review. Such articles should be addressed to : The Secretary-General, I nternational H ydrographic B u r e a u Quai de Plaisance Mo n te -C arlo (Principality of Monaco) and should reach him not later than 1st February or ist August for the May or November numbers respectively. INDEX OF ARTICLES AND AUTHORS for the First Twenty-four Numbers MARCH 1923 - NOVEMBER 1935 FOREWORD This Index is in two parts : P a r t I. — Classification of articles according to the Subjects dealt with. P a r t II. — Alphabetical Index of the names of Authors of articles which have been published in The Hydrographic Review. NOTE. — Articles marked (R ) are Reviews of publications. Articles marked (E) are Extracts from publications. When no author’s name is given, articles have been compiled from information received by the Interna tional Hydrographic Bureau. Reviews of Publications appear under the name or initials of the author of the review. Descriptions of instruments or appliances are given in the chapters relating to their employment, in Chapter XIV (Various Instruments), or occasionally in Chapter XXT (Hints to Hydrographic Surveyors). CLASSIFICATION OF ARTICLES ACCORDING TO THE SUBJECTS DEALT WITH List of subjects I . — H ydrographic Offic e s a n d o th er Mar itim e a n d S c ie n t ific Organisations (Patrols, Life- saving, Observatories, Institutes of Optics)..................................................................................... -

Early & Rare World Maps, Atlases & Rare Books

19219a_cover.qxp:Layout 1 5/10/11 12:48 AM Page 1 EARLY & RARE WORLD MAPS, ATLASES & RARE BOOKS Mainly from a Private Collection MARTAYAN LAN CATALOGUE 70 EAST 55TH STREET • NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10022 45 To Order or Inquire: Telephone: 800-423-3741 or 212-308-0018 Fax: 212-308-0074 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.martayanlan.com Gallery Hours: Monday through Friday 9:30 to 5:30 Saturday and Evening Hours by Appointment. We welcome any questions you might have regarding items in the catalogue. Please let us know of specific items you are seeking. We are also happy to discuss with you any aspect of map collecting. Robert Augustyn Richard Lan Seyla Martayan James Roy Terms of Sale: All items are sent subject to approval and can be returned for any reason within a week of receipt. All items are original engrav- ings, woodcuts or manuscripts and guaranteed as described. New York State residents add 8.875 % sales tax. Personal checks, Visa, MasterCard, American Express, and wire transfers are accepted. To receive periodic updates of recent acquisitions, please contact us or register on our website. Catalogue 45 Important World Maps, Atlases & Geographic Books Mainly from a Private Collection the heron tower 70 east 55th street new york, new york 10022 Contents Item 1. Isidore of Seville, 1472 p. 4 Item 2. C. Ptolemy, 1478 p. 7 Item 3. Pomponius Mela, 1482 p. 9 Item 4. Mer des hystoires, 1491 p. 11 Item 5. H. Schedel, 1493, Nuremberg Chronicle p. 14 Item 6. Bergomensis, 1502, Supplementum Chronicum p. -

Bulletin De La Sabix, 39 | 2005 Géodésie, Topographie Et Cartographie 2

Bulletin de la Sabix Société des amis de la Bibliothèque et de l'Histoire de l'École polytechnique 39 | 2005 André-Louis Cholesky (1875-1918) Géodésie, topographie et cartographie C. Brezinski Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/sabix/525 DOI : 10.4000/sabix.525 ISSN : 2114-2130 Éditeur Société des amis de la bibliothèque et de l’histoire de l’École polytechnique (SABIX) Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 décembre 2005 Pagination : 32 - 66 ISBN : ISSN N° 2114-2130 ISSN : 0989-30-59 Référence électronique C. Brezinski, « Géodésie, topographie et cartographie », Bulletin de la Sabix [En ligne], 39 | 2005, mis en ligne le 07 décembre 2010, consulté le 21 décembre 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ sabix/525 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/sabix.525 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 21 décembre 2020. © SABIX Géodésie, topographie et cartographie 1 Géodésie, topographie et cartographie C. Brezinski 1 La géodésie s’occupe de la détermination mathématique de la forme de la Terre. Les observations géodésiques conduisent à des données numériques : forme et dimensions de la Terre, coordonnées géographiques des points, altitudes, déviations de la verticale, longueurs d’arcs de méridiens et de parallèles, etc. 2 La topographie est la sœur de la géodésie. Elle s’intéresse aux mêmes quantités, mais à une plus petite échelle, et elle rentre dans des détails de plus en plus fins pour établir des cartes à différentes échelles et suivre pas à pas les courbes de niveau. La topométrie constitue la partie mathématique de la topographie. 3 La cartographie proprement dite est l’art d’élaborer, de dessiner les cartes, avec souvent un souci artistique. -

Knowing and Decorating the World Illustrations and Textual Descriptions in the Maps of the Fourth Edition of the Mercator-Hondius Atlas (1613)

OTTO LATVA AND JOHANNA SKURNIK Knowing and decorating the world Illustrations and textual descriptions in the maps of the fourth edition of the Mercator-Hondius Atlas (1613) his article analyses the Mercator-Hondius Atlas depicted on the maps authored by Mercator and maps in the context of constructing knowl- Hondius. We investigate the illustrations and textual Tedge of the world. In what follows, we analyse descriptions Mercator and Hondius used to represent the elem ents of continental geographies and ocean the world and its regions. These two men each applied spaces on the maps presented in the atlas. We take as very different principles when preparing maps: our starting point the tension between empirical and Mercator considered himself to be a scholar aiming theoretical knowledge and examine the changes occur- to produce the most accurate maps and emphasizing ring in the ways of representing land and sea on atlas their informative content. Hondius, however, evolved maps which are evident in the Mercator-Hondius Atlas. from an engraver to a publisher of atlases and globes, Consequently, we investigate how the world was rep- turning them into a profitable business (van der resented through information in pictorial and textual Krogt 1997: 35; Zuber 2011: 516). We argue that the form. We argue that the maps in the Mercator-Hondius maps in the Mercator-Hondius Atlas can be read as a Atlas make explicit not only the multiple cartographical demonstration of the layered nature of the atlas as an trad itions and the layered nature of atlases as artefacts. epistemological artefact. They also exemplify the various coexisting functions of The principles and practices employed by dif- the atlas.