“The Touch of Cold Philosophy”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PRESSENS ROLLE I ÅRENE ETTER 1814 Pressehistorisk Tidsskrift Nr

Ruth Hemstad: Propagandakrigen om Norge i europeisk presse Odd Arvid Storsveen: Aviser som politiske aktører på 1800-tallet Marthe Hommerstad: Politisk debatt mellom den dannede elite og bøndene rundt 1814 Rune Ottosen: Matthias Conrad Peterson og kampen for ytringsfrihet Håkon Harket: Jødenes utestengelse fra Norge Nils Øy: Er slangene i § 100 borte etter 200 år? Stian Eisenträger: Den europeiske presse og norsk uavhengighet i 1814 Mona Ringvej: Å gi allmuen en stemme i offentligheten Hans Fredrik Dahl: Pressen og samfunnsoppdraget etter 1814 Nils E. Øy: Fredrikstad Tidende, svenskenes okkupasjonsavis Olav Kobbeltveit: Norsk presses dekning av 100-årsjubileet for Grunnlova Gøril Strømholm: Presseminne – 40 år siden feministbladet Sirene PRESSENS ROLLE I ÅRENE ETTER 1814 Pressehistorisk tidsskrift nr. 23 2015 Norsk Pressehistorisk Forening www.pressetidsskrift.no Pressens rolle i årene etter 1814 Utgitt av Norsk Pressehistorisk Forening Redaksjon for dette nummeret av Pressehistorisk Tidsskrift: Erika Jahr (ansv. red.) Marte Stapnes (red.sekr.) © 2015 Forfatterne Ikke-krediterte foto: Materiale i det fri. Hentet fra Wikmedia Commons. Design: Endre Barstad Omslagsfoto: Slaget ved Hanau, 1814 hvor Napoleons hær beseiret østerrikerne og bayerne. Kilde: WikiMedia Commons Grafisk produksjon: Endre Barstad ISSN Digital utgave 2387-3655 Utgitt av Norsk Pressehistorisk Forening Digitalt abonnementet er inkludert i medlemskontingenten. Adresse: Norsk Pressehistorisk Forening c/o Mediebedriftenes Landsforening Kongensgate 14 0153 Oslo Hjemmeside: www.pressetidsskrift.no Redaksjonsadresse: Pressehistorisk tidsskrift v/ Redaktør Erika Jahr Drammensveien 113 0273 Oslo Telefon: 97141306 E-post: [email protected] 5 PRESSEHISTORISK TIDSSKRIFT NR. 23 2015 Leder: Pressens rolle etter 1814 Sohm satte opp i festningsbyen, gir innblikk i en inn- Erika Jahr bitt propaganda for å gjøre nordmennene vennlige- Redaktør [email protected] re stemt mot Sverige. -

The Writings of Marsilio Ficino and Lodovico Lazzarelli

Iskander Israel Rocha Parker CONFLICTING CONCEPTIONS OF HERMETIC THOUGHT IN FIFTEENTH CENTURY ITALY: THE WRITINGS OF MARSILIO FICINO AND LODOVICO LAZZARELLI MA Thesis in Comparative History, with a specialization in Late Antique, Medieval, and Renaissance Studies. Central European University Budapest June 2020 CEU eTD Collection CONFLICTING CONCEPTIONS OF HERMETIC THOUGHT IN FIFTEENTH CENTURY ITALY: THE WRITINGS OF MARSILIO FICINO AND LODOVICO LAZZARELLI by Iskander Israel Rocha Parker (Mexico) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Comparative History, with a specialization in Late Antique, Medieval, and Renaissance Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner ____________________________________________ CEU eTD Collection Examiner Budapest Month YYYY CONFLICTING CONCEPTIONS OF HERMETIC THOUGHT IN FIFTEENTH CENTURY ITALY: THE WRITINGS OF MARSILIO FICINO AND LODOVICO LAZZARELLI by Iskander Israel Rocha Parker (Mexico) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Comparative History, with a specialization in Late Antique, Medieval, and Renaissance Studies. Accepted in conformance -

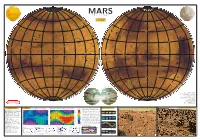

Appendix I Lunar and Martian Nomenclature

APPENDIX I LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE A large number of names of craters and other features on the Moon and Mars, were accepted by the IAU General Assemblies X (Moscow, 1958), XI (Berkeley, 1961), XII (Hamburg, 1964), XIV (Brighton, 1970), and XV (Sydney, 1973). The names were suggested by the appropriate IAU Commissions (16 and 17). In particular the Lunar names accepted at the XIVth and XVth General Assemblies were recommended by the 'Working Group on Lunar Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr D. H. Menzel. The Martian names were suggested by the 'Working Group on Martian Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr G. de Vaucouleurs. At the XVth General Assembly a new 'Working Group on Planetary System Nomenclature' was formed (Chairman: Dr P. M. Millman) comprising various Task Groups, one for each particular subject. For further references see: [AU Trans. X, 259-263, 1960; XIB, 236-238, 1962; Xlffi, 203-204, 1966; xnffi, 99-105, 1968; XIVB, 63, 129, 139, 1971; Space Sci. Rev. 12, 136-186, 1971. Because at the recent General Assemblies some small changes, or corrections, were made, the complete list of Lunar and Martian Topographic Features is published here. Table 1 Lunar Craters Abbe 58S,174E Balboa 19N,83W Abbot 6N,55E Baldet 54S, 151W Abel 34S,85E Balmer 20S,70E Abul Wafa 2N,ll7E Banachiewicz 5N,80E Adams 32S,69E Banting 26N,16E Aitken 17S,173E Barbier 248, 158E AI-Biruni 18N,93E Barnard 30S,86E Alden 24S, lllE Barringer 29S,151W Aldrin I.4N,22.1E Bartels 24N,90W Alekhin 68S,131W Becquerei -

In Pdf Format

lós 1877 Mik 88 ge N 18 e N i h 80° 80° 80° ll T 80° re ly a o ndae ma p k Pl m os U has ia n anum Boreu bal e C h o A al m re u c K e o re S O a B Bo l y m p i a U n d Planum Es co e ria a l H y n d s p e U 60° e 60° 60° r b o r e a e 60° l l o C MARS · Korolev a i PHOTOMAP d n a c S Lomono a sov i T a t n M 1:320 000 000 i t V s a Per V s n a s l i l epe a s l i t i t a s B o r e a R u 1 cm = 320 km lkin t i t a s B o r e a a A a A l v s l i F e c b a P u o ss i North a s North s Fo d V s a a F s i e i c a a t ssa l vi o l eo Fo i p l ko R e e r e a o an u s a p t il b s em Stokes M ic s T M T P l Kunowski U 40° on a a 40° 40° a n T 40° e n i O Va a t i a LY VI 19 ll ic KI 76 es a As N M curi N G– ra ras- s Planum Acidalia Colles ier 2 + te . -

Renaissance Studies Humanities 312W Section

Renaissance Studies Humanities 312W Section: J100 Term: 2011 Spring Instructor: Dr. Brook W.R. Pearson Discussion Topics: One of the generally recognized defining characteristics of Renaissance culture is a turn (back) towards aspects of classical culture that had been neglected in Europe during the Medieval period. This course will be concerned with an aspect of this turn, namely the way in which the esoteric discourses of recently rediscovered Hermetic thought played a role in the development of Renaissance philosophy and science. Hermeticism, a mixture of astrology, magic, alchemy, philosophy and religious thought deriving (likely) from Egyptian thinkers in the 2nd4th centuries, was reintroduced to Europe during the 15th century, and would go on to influence a number of significant thinkers throughout the Renaissance and the Enlightenment. Though we will focus primarily upon Florentine Hermetic thinkers of the 15th century, course presentations will also look at some modern connections to this material. We will also pay attention to the political setting of this material, as it is Cosimo de Medici (13891464), founder of the Florentine Medici dynasty, to whom we owe the re-discovery of the Corpus Hermeticum. Cosimo is well known to have exercised his influence in Italian culture through economic, political, religious but also more broadly scholarly and cultural channels. He founded the Florentine Academy, headed by Marsilio Ficino, among whose students number both Giordano Bruno and Pico della Mirandola, and even, possibly, Michelangelo. Through such thinkers, the influence of Hermeticism extended throughout European scholarly discourse. Grading: 50% = Term Paper \x09\x09 \x095% = Topic Proposal \x09 \x0910% = Annotated bibliography and outline \x09 \x0925% = First draft \x09 \x0910% = Finished product (20 pages) \x09 35% = Presentation \x09 15% = Class/Seminar Participation \x09 Required Texts: Giordano Bruno (ed. -

1 James Hankins Department of History Harvard University Chronological List of Publications

1 James Hankins Department of History Harvard University Chronological List of Publications IN PRESS “Petrarch and the Canon of Neo-Latin Literature” to be published in the proceedings of the conference the conference “Petrarca, l’Umanesimo e la civiltà europea,” Florence, Italy, December 2004, sponsored the Comitato Nazionale per il VII Centenario della Nascita di Francesco Petrarca. “The Chronology of Leonardo Bruni’s Later Works (1437-1443).” Forthcoming in Studi medievali e umanistici 5 (2007). “Monstrous Melancholy: Ficino and the Physiological Causes of Atheism,” forthcoming in a volume tentatively entitled, Laus Platonici philosophi: Marsilio Ficino and His Influence,” ed. Stephen Clucas and Valerie Rees (Brill). “Malinconia mostruosa: Ficino e le cause fisiologiche dell’atesimo,” the same in Italian translation, forthcoming in Rinascimento 2007. “Humanist Academies and Platonic Academies,” forthcoming in the proceedings of the conference, From the Roman Academy to the Danish Academy in Rome, ed. H. Ragn Jensen and M. Pade, to appear in Analecta Romana Instituti Danici Supplementum. French and Italian translations of Plato in the Italian Renaissance (1990) are to appear, respectively, with Les Belles Lettres (Paris), tr. Yves-Alain Segonds, and the press of the Scuola Normale Superiore, Pisa (Edizioni del SNS), tr. Stefano Baldassarri. A new, revised edition of the English original is forthcoming from Brill. 2008 111. (with Ada Palmer). The Recovery of Ancient Philosophy in the Renaissance. A Brief Guide. (Istituto Nazionale di Studi sul Rinascimento, Quaderni di Rinascimento, vol. 44). Florence: Leo S. Olschki, 2008. VIII + 96 pp. 2 110. “Notes on the Composition and Textual Tradition of Leonardo Bruni’s Historiarum Florentini populi libri XII,” in Classica et Beneventana: Essays presented to Virginia Brown on the Occasion of her Sixty-Fifth Birthday, ed. -

107 V Ariations on the Unexpected

107 Variations on the Unexpected SURPRISE 107 Variations on the Unexpected Dedication and Prelude To Raine Daston In his essay “Of Travel,” Francis Bacon recommends that diaries be used to register the things “to be seen and observed.” Upon returning home, the traveler should not entirely leave the visited countries, but maintain a correspondence with those she met, and let her experi- ence appear in discourse rather than in “apparel or gesture.” Your itineraries through a vast expanse of the globe of knowledge seem to illustrate Bacon’s recommendations, and have inspired many to em- bark on the exploration of other regions—some adjacent, some dis- tant from the ones you began to clear. Yet not all have journeyed as well equipped as you with notebooks, nor assembled them into a trove apt to become, as Bacon put it, “a good key” to inquiry. As you begin new travels, you may add the present collection to yours, and adopt the individual booklets as amicable companions on the plane or the U-Bahn. Upon wishing you, on behalf of all its contributors, Gute Reise! and Bon voyage!, let us tell you something about its gen- esis and intention. Science depends on the unexpected. Yet surprise and its role in the process of scientific knowledge-making has hitherto received lit- tle attention, let alone systematic investigation. If such a study ex- isted, it would no doubt have been produced in your Department at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science. The topic is a seamless match with your interest in examining ideals and practices of scientific and cultural rationality—ideals and practices often so fundamental that they appear to transcend history or are overlooked altogether. -

A Classified Bibliography on the History of Scientific Instruments by G.L'e

A Classified Bibliography on the History of Scientific Instruments by G.L'E. Turner and D.J. Bryden Originally published in 1997, this Classified Bibliography is "Based on the SIC Annual Bibliographies of books, pamphlets, catalogues and articles on studies of historic scientific instruments, compiled by G.L'E. Turner, 1983 to 1995, and issued by the Scientific Instrument Commission. Classified and edited by D.J. Bryden" (text from the inside cover page of the original printed document). Dates for items in this bibliography range from 1979 to 1996. The following "Acknowledgments" text is from page iv of the original printed document: The compiler thanks the many colleagues throughout the world who over the years have drawn his attention to publications for inclusion in the Annual Bibliography. The editor thanks Miss Veronica Thomson for capturing on disc the first 6 bibliographies. G.L'E. Turner, Oxford D.J. Bryden, Edinburgh April 1997 ASTROLABE ACKERMANN, S., ‘Mutabor: Die Umarbeitung eines mittelalterlichen Astrolabs im 17. Jahrhundert’, in: von GOTSTEDTER, A. (ed), Ad Radices: Festband zum fünfzigjährrigen Bestehen des Instituts für Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften der Johann Wolfgang Goethe- Universtät Frankfurt am Main (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1994), 193-209. ARCHINARD, M., Astrolabe (Geneva: Musée d'histoire des Sciences de Genève, 1983). 40pp. BORST, A., Astrolab und Klosterreform an der Jahrtausendwende (Heidelberg: Carl Winter Universitatsverlag, 1989) (Sitzungsberichte der Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften Philosophisch-historische Klasse). 134pp. BROUGHTON, P., ‘The Christian Island "Astrolabe" ’, Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, 80, no.3 (1986), 142-53. DEKKER, E., ‘An Unrecorded Medieval Astrolabe Quadrant c.1300’, Annals of Science, 52 (1995), 1-47. -

The Evolution of Individualism Through Christianity A

THE EVOLUTION OF INDIVIDUALISM THROUGH CHRISTIANITY A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of The School of Continuing Studies and of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Liberal Studies By Maureen Heath, M.P.A. Georgetown University Washington D.C. April 2018 DEDICATION I would like to thank my husband Dr. Jim Heath, who has been a source of constant motivation and support. He encouraged me to pursue the doctorate and has diligently read and edited multiple iterations of this thesis. I would also like to thank all the members of my committee: Dr. Frank Ambrosio, Dr. Bill O’Brien and especially Dr. JoAnn H. Moran Cruz, who has spent many hours mentoring me and guiding me through this process. ii THE EVOLUTION OF INDIVIDUALISM THROUGH CHRISTIANITY Maureen Heath DLS Chair: JoAnn Moran Cruz, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This thesis explores how Christianity and the birth of a Christian worldview affected the evolution of individualism in Western culture as a cultural meme. Applying a biological metaphor, the focus is on how mutations in the cultural genome arose from the advent of Christianity within a Eurocentric context. Utilizing a diachronic examination of selected authors and writings, this thesis explores that cultural evolution and shows the progression to the modern individual. Beginning with Augustine and extending to John Locke, the focus is on writers who are emblematic of a concept that becomes an adaptive trait or cultural meme in the evolutionary process. They include: Augustine exhibiting the inner self, Abelard and Ockham displaying the intentional self, Dante manifesting the responsible self, Pico della Mirandola and the self-made man, Montaigne presenting the subjective self, Luther with the autonomous-self meme, and Locke presenting the natural rights meme. -

Article: XXVIII, Le 2 Septembre 1859, (Letter Du R

CMYK RGB Hist. Geo Space Sci., 3, 33–45, 2012 History of www.hist-geo-space-sci.net/3/33/2012/ Geo- and Space doi:10.5194/hgss-3-33-2012 © Author(s) 2012. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Access Open Sciences Advances in Science & Research Open Access Proceedings Father Secchi and the first Italian magnetic observatoryDrinking Water Drinking Water Engineering and Science N. Ptitsyna1 and A. Altamore2 Engineering and Science Open Access Access Open Discussions 1Institute of Terrestrial Magnetism, Ionosphere and Radiowave Propagation, Russian Academy of Science, St. Petersburg Filial, Russia 2Physical Department “E. Amaldi”, University “Roma Tre”, Rome, Italy Discussions Earth System Earth System Correspondence to: N. Ptitsyna ([email protected]) Science Science Received: 23 October 2011 – Revised: 19 January 2012 – Accepted: 30 January 2012 – Published: 28 February 2012 Open Access Open Abstract. The first permanent magnetic observatory in Italy was built in 1858 by Pietro AngeloAccess Open Data Secchi, a Data Jesuit priest who made significant contributions in a wide variety of scientific fields, ranging from astronomy to astrophysics and meteorology. In this paper we consider his studies in geomagnetism, which have never Discussions been adequately addressed in the literature. We mainly focus on the creation of the magnetic observatory on the roof of the church of Sant’Ignazio, adjacent to the pontifical university, known as the CollegioSocial Romano. Social From 1859 onwards, systematic monitoring of the geomagnetic field was conducted in the Collegio Romano Open Access Open Geography Observatory, for long the only one of its kind in Italy. We also look at the magnetic instrumentsAccess Open Geography installed in the observatory, which were the most advanced for the time, as well as scientific studies conducted there in its early years. -

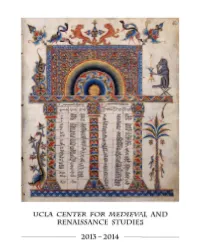

2013-14 Academic Year: Will Meet at the Huntington Library to Discuss Four Pre- Distributed Research Papers

TABLE OF CONTENTS A Message from the Director, October 2013..............................................................................................2 CMRS Hosts MAA–MAP at UCLA.........................................................................................................3 Lectures, Conferences, and other Events, 2013 – 2014........................................................................4 – 9 Visiting Faculty, Students, and Scholars..............................................................................................10–11 Distinguished Visiting Scholars, 2013 – 2014 CMRS Summer Fellows Ahmanson Research Fellows UCLA Visiting Scholars affiliated with CMRS Visiting Graduate Researchers Publications.....................................................................................................................................12 – 15 Viator Repertorium Columbianum Cursor Mundi Comitatus International Encyclopaedia for the Middle Ages–Online Other CMRS Publication Projects A Checklist of CMRS Events, 2013 – 2014....................................................................................16 – 17 Student Support and Programs........................................................................................................18 – 19 George T. and Margaret W. Romani Fellowship CMRS Travel Grants CMRS Seminars Ahmanson Research Fellowships for the Study of Medieval and Renaissance Books and Manuscripts CMRS Research Assistantships Lynn and Maude White Fellowship Medieval and Early Modern Student Association -

Downloaded License

Aries – Journal for the Study of Western Esotericism 21 (2021) 271–278 ARIES brill.com/arie Review Essays ∵ A New Volume of Perfect Words M. David Litwa’s Hermetica ii Dylan M. Burns University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands [email protected] M. David Litwa, Hermetica ii: The Excerpts of Stobaeus, Papyrus Fragments, and Ancient Testimonies in an English Translation with Notes and Introductions (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018). isbn: 978-1-107-18253-0 The main impetus for this book is the absence of an up-to-date English trans- lation of significant materials, mostly pertaining to ‘philosophical Hermet- ica’—philosophically-inclined literature of Roman and late antiquity that fea- tures the Hellenistic Egyptian culture-hero Hermes Trismegistus (“thrice- greatest”)—that are not found in Brian Copenhaver’s celebrated 1992 Cam- bridge translation of the Corpus Hermeticum and Latin Asclepius.1 The mate- 1 Brian Copenhaver, tr., Hermetica: The Greek ‘Corpus Hermeticum’ and the Latin ‘Asclepius’ in a new English translation, with notes and introduction (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992). Abbreviations of Hermetic fragments and testimonies: fh: Fragments of Hermetica sh: Stobaeus (Fragments of) Hermetica th: Testimonies of Hermetica Abbreviations of modern resources on Hermetica: chd: Jens Holzhausen, tr., Corpus Hermeticum Deutsch (2 vols.; Stuttgart-Bad Cannsatt: Frommann-Holzboog, 1997). Litwa: M. David Litwa, Hermetica ii, under review here. © dylan m. burns, 2021 | doi:10.1163/15700593-02102003 This is an