Chapter 1 Introduction and Background

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Society for Ethnomusicology 58Th Annual Meeting Abstracts

Society for Ethnomusicology 58th Annual Meeting Abstracts Sounding Against Nuclear Power in Post-Tsunami Japan examine the musical and cultural features that mark their music as both Marie Abe, Boston University distinctively Jewish and distinctively American. I relate this relatively new development in Jewish liturgical music to women’s entry into the cantorate, In April 2011-one month after the devastating M9.0 earthquake, tsunami, and and I argue that the opening of this clergy position and the explosion of new subsequent crises at the Fukushima nuclear power plant in northeast Japan, music for the female voice represent the choice of American Jews to engage an antinuclear demonstration took over the streets of Tokyo. The crowd was fully with their dual civic and religious identity. unprecedented in its size and diversity; its 15 000 participants-a number unseen since 1968-ranged from mothers concerned with radiation risks on Walking to Tsuglagkhang: Exploring the Function of a Tibetan their children's health to environmentalists and unemployed youths. Leading Soundscape in Northern India the protest was the raucous sound of chindon-ya, a Japanese practice of Danielle Adomaitis, independent scholar musical advertisement. Dating back to the late 1800s, chindon-ya are musical troupes that publicize an employer's business by marching through the From the main square in McLeod Ganj (upper Dharamsala, H.P., India), streets. How did this erstwhile commercial practice become a sonic marker of Temple Road leads to one main attraction: Tsuglagkhang, the home the 14th a mass social movement in spring 2011? When the public display of merriment Dalai Lama. -

Les Minorités Tamoules À Colombo, Kuala Lumpur Et Singapour : Minorités, Intégrations Socio-Spatiales Et Transnationalités Delon Madavan

Les minorités tamoules à Colombo, Kuala Lumpur et Singapour : Minorités, intégrations socio-spatiales et transnationalités Delon Madavan To cite this version: Delon Madavan. Les minorités tamoules à Colombo, Kuala Lumpur et Singapour : Minorités, inté- grations socio-spatiales et transnationalités. Géographie. Université Paris IV - Paris Sorbonne, 2013. Français. tel-01651800 HAL Id: tel-01651800 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01651800 Submitted on 29 Nov 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. UNIVERSITÉ PARIS-SORBONNE ÉCOLE DOCTORALE de Géographie de Paris Laboratoire de recherche Espaces, nature et culture T H È S E pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR DE L’UNIVERSITÉ PARIS-SORBONNE Discipline/ Spécialité : Géographie Présentée et soutenue par : Delon MADAVAN le : 26 septembre 2013 Les minorités tamoules à Colombo, Kuala Lumpur et Singapour : Minorités, intégrations socio-spatiales et transnationalités Sous la direction de : Monsieur Olivier SEVIN, Professeur, Université Paris-Sorbonne JURY : Monsieur Christian HUETZ DE LEMPS, Professeur -

Hindu Religious Practices Exposed in Malaysian Tamil Movies

Hindu Religious Practices Exposed in Malaysian Tamil Movies K. SillIalee I M. Rajantherarr' Abstract Late 19th and ear1y 20th centuries marks the mass migration of people from India to Malaya to work in estates while minority of them came as merchants and to work incivil service. The majority group started their religious practice by worshiping the demigods. On the other hand, the minority group settled in urban areas and they initiated the proper religious practice by building temples for the main deities such as Lord Siva, Lord Muruga as well as Lord Vishnu. After the independence of Malaya, many of those residing in the estates began to shift to urban areas for improvements in their life. These people began to have realisation on the actual way of religious practice and were attracted to the prayers to the main deities such as Lord Shiva and Lord Muruga. Currently, besides the prayers to the main deities, Malaysian Indians have high level or spiritual awareness such as meditation and Siddha philosophy. Though there is a significant evidence or religious awareness among Malaysian Indians, Tamil movies produced in Malaysia still centres in the olden religious practice and the worship to demigods. As such, this research intends to explore the reason for the production of such themes in local Tamil movies. Besides, the researcher also wants to find out the reality in comparison to the movie projections. This research also would shed light the movie of the local Tamil movie producer in exposing the olden religious practice rather than the reality. Keywords: Hindu Religious, Malaysian Tamil Movies, Malaysian Indians, Beliefs, Great Traditions Mr K S~lllalec is currently a Ph.D research candidate at the Department of Indian Studies, Faculty of Arts and SocIal Science, University of Malaya (Malaysia) who has a keen interest in tile field of Hindu religion and CUlture. -

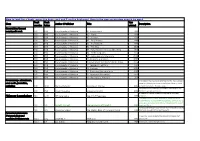

MCG Library Book List Excel 26 04 19 with Worksheets Copy

How to look for a book: press the keys cmd and F on the keyboard, then in the pop up window search by word Book Book Year Class Author / Publisher Title Description number letter printed Generalities/General encyclopedic work 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 01- Environment 1998 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 02 - Plants 1998 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 03 - Animals 1998 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 04 - Early History 1998 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 05 - Architecture 1998 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 06 - The Seas 2001 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 07 - Early Modern History (1800-1940) 2001 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 08 - Performing Arts 2004 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 09 - Languages and Literature 2004 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 10- Religions and Beliefs 2005 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 11-Government and Politics (1940-2006) 2006 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 12- Peoples & Traditions 2007 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 13- Economy 2007 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 14- Crafts and the visual arts 2007 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 15- Sports and Recreation 2008 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 16- The rulers of Malaysia 2011 Documentary-, educational-, In this book Marina draws attention to the many dangers news media, journalism, faced by Malaysia, to concerns to fellow citizens, social publishing 070 MAR Marina Mahathir Dancing on Thin Ice 2015 and political affairs. Double copies. Compilations of he author's thought, reflecting on the 070 RUS Rusdi Mustapha Malaysian Graffiti 2012 World, its people and events. Principles of Tibetan Buddhism applied to everyday Philosopy & psychology 100 LAM HH Dalai Lama The Art of Happiness 1999 problems As Nisbett shows in his book people think about and see the world differently because of differing ecologies, social structures, philosophies and educational systems that date back to ancient 100 NIS Nisbett, Richard The Geography of thought 2003 Greece and China. -

(2) Chedet.Co.Cc September 5, 2008 by Dr. Mahathir Mohamad 1. I Had

POHON MAAF (2) Chedet.co.cc September 5, 2008 By Dr. Mahathir Mohamad 1. I had hesitated about writing the Pohon Maaf article even. I thought I would surely be misunderstood. I would be accused of being a racist. 2. Sure enough, although many agree with me, some felt sad that I had become a racist, others merely use nasty words against me. 3. When the opposition did very well in the 2008 elections, foreign observers talk about a wind of change in Malaysia; about how racialism had been rejected, how Anwar, their favourite would soon take over the Government. 4. I had differed from these casual observers because I know that it was not rejection of racial politics which helped the opposition. It was simply disgust on the part of members of UMNO, MCA and Gerakan of the Premiership and leadership of Dato Seri Abdullah Ahmad Badawi. Talking on the ground, this was quite obvious. 5. Far from the opposition's "win" being brought about by rejection of racial politics, it has actually enhanced racial politics. We talk more about race and racial interest than we did in the last 50 years. 6. The Malays are feeling the loss of their political base and the Chinese and Indians appear to be glorifying in the new political clout. As a result, subjects which we before regarded as sacrosanct are now brought up and made to be entirely in favour of the Malays. 7. Against this unfamiliar attack against them, the Malays are unable to counter. Their leaders have deserted them. -

Negotiating Identities in the Diasporic Space: Transnational Tamil Cinema and Malaysian Indians

Negotiating identities in the Diasporic Space: Transnational Tamil Cinema and Malaysian Indians Gopalan Ravindran Abstract One of the significant transformations brought about by globalization is the transnationalization of diasporic cinemas. A case in point is the growth of diasporic cinemas catering to the varied diasporas of Indian origin. One of the most important diasporas cinema is Tamil cinema. Negotiations of identities in the Tamil diasporic space are mediated by a variety of sources ranging from Tamil films, Tamil internet, Tamil satellite television/radio and Tamil newspapers/magazines, beside interpersonal sources. Even though, studies have not been done on the relative influence of the above sources, it is apparent that in countries like Malaysia and Singapore, Tamils films are having a perceptible influence among different sections of the Indian population. This paper aims to examine the role of transnational Tamil cinema in Malaysia with a focus on Malaysian Tamil cinema audience's negotiations of cultural identities in the diasporic space Cultural Space and Public Sphere in Asia 2006, Seoul, Korea / 240 Introduction The notion of film spectators is bridled with as many adequacies as there are inadequacies. The plight of the notion of film audience is no different. Notwithstanding the seemingly simple similarity between the two, there are divergent views of their locations (Meers,2001; Fuller-Seeley,2001) While the film spectator is positioned as the dreaming and individualistic psychological material before the screen (Rascaroli,2002), members of film audience are seen as belonging to collectives that are constituted by socio-cultural conditions. Such collectives are also recognizable, empirically and otherwise; in contrast to the dreaming film spectators. -

Perspectives on Language Policies in Malaysia

Durham E-Theses Perspectives on language policies in Malaysia Mariasoosay, Thanaraj How to cite: Mariasoosay, Thanaraj (1996) Perspectives on language policies in Malaysia, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/5185/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk PERSPECTIVES ON LANGUAGE POLICIES IN MALAYSIA by THANARAJ MARIASOOSAY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN EDUCATION The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without the written consent of the author and information derived from it should be acknowledged. SCHOOL OF EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF DURHAM 1996 ^ MAR 1998 PERSPECTiyES ON LANGUAGE POLICIES IN MALAYSLV by Thanaraj Mariasoosay for Master of Arts in Education 1996 ABSTRACT alaysia is a multi-cultural society with major ethnic divisions between MMalays, Chinese and Indians, each group having associated linguistic and religious affiliations which intensify the divisions of Malaysian society. -

Language Change and Maintenance of Tamil Language in the Multilingual Context of Malaysia

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org ||Volume 5 Issue 12||December. 2016 || PP.55-60 Language Change and Maintenance of Tamil language in the Multilingual Context of Malaysia Paramasivam Muthusamy, Atieh Farashaiyan University Putra Malaysia University Kebangsaan Malaysia ABSTRACT: The prevailing multilingual situation of Malaysia reflects the gradual shift in the use of minority languages (ethnic) like Tamil, both in formal as well as informal domains of language use. There are several reasons for language shift to take place in the maintenance of language, and one such is the existing power that goes with language(s). How Far language attitudes, linguistic views and power based policies will poster the use of concerned language for the benefit of society at large is indeed a challenge and seems to be a question mark. The Malaysian Tamil society is gradually shifting to language like English and Bahasa Malaysia as media of instruction to achieve education needs in different displaces of knowledge, considering the modern economic- scientific and technological – occupational- developmental progress and needs of the society. Moreover, these kinds of existing rigidity in attitude towards language use and emotionally motivated views might cause problems in the long run for society in getting education or employment opportunities. Language policies has made mandatory use of Malay education, use of the English language at different levels with power and efficiency, use of mother- tongue languages in education and mass media as far as possible. The present day generation prefer training in job-oriented, application and practice oriented education, so they are forced to shift from their mother- tongue to the national language or English for specific purposes. -

Wong, V.X. 2018.Pdf

FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES SCHOOL OF EDUCATION, COMMUNICATION AND LANGUAGE SCIENCES A STUDY OF MIXED LANGUAGE USE AMONG TWO SOCIAL GROUPS OF EAST MALAYSIAN MULTILINGUALS IN INFORMAL SETTINGS Victoria Xinyi Wong Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Applied Linguistics & Communication Newcastle, June 2018 FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES SCHOOL OF EDUCATION, COMMUNICATION AND LANGUAGE SCIENCES DECLARATION I hereby certify that this thesis is based on my original work except for quotations and citations, which have been duly acknowledged. I also declare that it has not been or is currently submitted for any other degree at the University of Newcastle or other institutions. Name: Victoria Xinyi Wong Signature: Date: 15/6/2018 Abstract Malaysia is a nation of considerable multi-ethnolinguistic variety. Comprising thirteen states (eleven located on the mainland, two situated in island Southeast Asia), diversity is evident between the many officially categorised ethnic groups, as well as within them (blurring official ethnic categories). Bi- or multilingualism is the norm throughout Malaysia, albeit more prevalent among minorities and in certain areas, especially those that are urban and/or are locations of ethnic diversity. Code- switching and translanguaging are common enough not to be remarkable outside of formal public discourse and mono-ethnolinguistic situations. This study was undertaken in East Malaysia, Sarawak, and takes an ethnographic approach. In order to try and make sense of the ways in which East Malaysian speakers express themselves, participant observation was undertaken in a family and a friendship domain, respectively. Speech events were informal and naturally occurring, during which family members and, separately, a group of friends interact in a variety of languages, illustrating the rich multilingual repertoires that participants can draw on. -

Social Meaning, Indexicality and Enregisterment of Manglish in Youth Whatsapp Chats

SOCIAL MEANING, INDEXICALITY AND ENREGISTERMENT OF MANGLISH IN YOUTH WHATSAPP CHATS Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy NUR HUSNA SERIP MOHAMAD Department of English School of the Arts September 2019 1 ABSTRACT Manglish, a variety of Malaysian English, has often been stereotyped in Malaysian media (i.e., local newspapers) as ‘improper English’ (Why Speak Manglish, 2007; Manglish-English Dilemma, 2007) or labelled by scholars as a type of ‘poor’, ‘broken’ English (Nair-Venugopal, 2013: 455). In fact, speakers of Manglish have been associated with ‘rural background’, ‘low-status’ in society, as well as ‘uneducated’ (Mahir, and Jarjis, 2007: 7). In recent years, there have been increasing debates on the status and use of Manglish, where it is a preferred variety of linguistic expression and is widely employed within certain contexts. The rise of Manglish has been hardly ignored in various social media platforms. This raises questions on how and why Manglish is employed or chosen as a language to communicate within online settings such as Instant Messaging. Thus, the (social) meanings that underlie Manglish communicative practices deserve exploration. This thesis seeks to contribute to the current discussion in linguistic studies on Manglish among three ethnic groups in Malaysia which are Malay, Chinese and Indian, by exploring how in-groupness and ethnic identity is reflected in the way speaker use Manglish features in WhatsApp conversation. More specifically, it focuses on the use of Manglish through the perspective of indexicality (Silverstein, 2003), social meaning (Eckert, 2003) and enregisterment (Agha, 2003). -

Voices of Malaysian Indian Writers Writing in English

Kajian Malaysia, Vol. 38, No. 2, 2020, 25–59 VOICES OF MALAYSIAN INDIAN WRITERS WRITING IN ENGLISH Shangeetha R.K. English Language Department, Faculty of Languages and Linguistics, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, MALAYSIA Email: [email protected] Published online: 30 October 2020 To cite this article: Shangeetha, R.K. 2020. Voices of Malaysian Indian writers writing in English. Kajian Malaysia 38(2): 25–59. https://doi.org/10.21315/km2020.38.2.2 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.21315/km2020.38.2.2 ABSTRACT This article brings together a compilation of poems, short stories and novels written by Malaysian Indian writers from 1940 to 2018. These verse and prose forms collected here were all written in English within the last 80 years. In fact, in the contemporary Malaysian literary scene, the number of works by Malaysian Indian writers writing in English, has increased compared to the previous volumes which were primarily dominated by writers such as Cecil Rajendra, K.S. Maniam and M. Shanmughalingam. It is interesting to note that the interest of writing poetry and prose among the younger Malaysian Indian writers is on the rise with publications from younger poets and writers such as Paul GnanaSelvam and Cheryl Ann Fernando. In Malaysia, poetry and prose written by Malaysian Indian writers in English is diversifying with many promising new talents. Departing from the Malaysian Indian diaspora, the emerging themes of these lesser-known writers are more liberal. As such, the main aim of this article is to map out the cartography of Malaysian Indian works in these three genres; poem, short story and novel, and identify the main thematic concerns in the writings. -

CONTENTS Festival Map Marquee Events 101 Talks, Workshops

CONTENTS 2 4 6 Forewords SWF Commission SWF Stage 16 18 22 Exhibitions Programmes: Programmes: 4 November 5–6 November 64 84 126 Programmes: Programmes: Country Focus: 7–11 November 12–13 Novmber Japan 131 139 193 Malay Conference Authors and SWF Programmes and Literary Pioneers Presenters for the Deaf 198 200 203 Visitor information Festival Map Acknowledgments INFORMATION IS CORRECT AS OF 5 OCTOBER. REFER TO SINGAPOREWRITERSFESTIVAL.COM FOR LATEST UPDATES. LEGEND Marquee 101 Talks, Workshops Family-friendly events events & Masterclasses (spot the events in different colours for easy reference!) Transcending Fun & Surprising Language and Genre Pop-ups FOREWORD The ritual is familiar to Singaporeans. Standing at a school assembly or a public function, you’d sing the lyrics of community tunes. They include 'Xiao Ren Wu De Xin Sheng' (Voices From The Heart), 'Munnaeru Vaalibaa' (Forward O Youth) and yes, 'Rasa Sayang' (Loving Feeling). Memories of belting out that last song welled up while my team and I were planning this year’s Singapore Writers Festival. But do we really know what the song means? Are we paying lip service to multi-lingualism, of getting to know each other? That is why we chose Sayang as the theme for this year’s festival. Found in Malay, Tagalog, Sundanese and various languages of the Malay Archipelago, the word ‘sayang’ means love and tenderness. Significantly, it also refers to regret Yeow Kai Chai and pity, delivered with a wistful sigh. We savour the nuances, its shades of loves Festival Director and losses. The word provides the guiding principle for our programming: What do we love and what sacrifices have we made? We are heartened, for instance, that you have embraced our inter-disciplinary approach last year, and we continue to do so this year, with productions, collaborations and lectures.