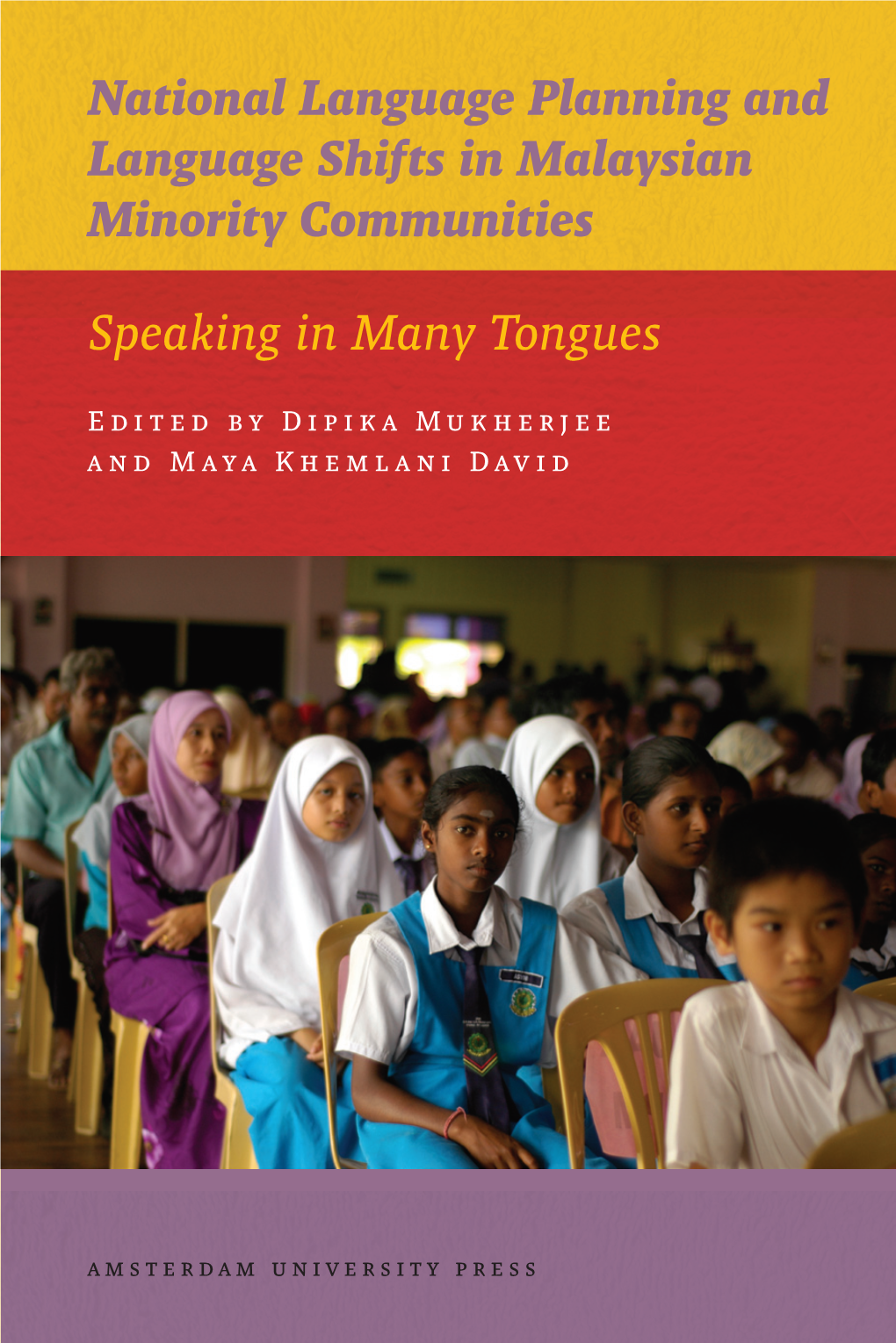

Speaking in Many Tongues Gathers the Work of Researchers Study- Speaking in Many Tongues Ing Language Change in Malaysia for Over Two Decades

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adelaidean August 2002

Adelaidean Volume 12 Number 7 News from the University of Adelaide August 2002 INSIDE National Information Roseworthy Science Week Day Information Day August 9-30 August 18 August 16 Space science Andy gives thumbs degree blasts up to space interest off in 2003 TWO new degrees—one in Space Students will also have opportunities to take Science and the other in Optics—are part in project work with established scientists expected to be in high demand at the in the field. University of Adelaide next year. "Direct exposure to professionals in the fields Both degrees offer a unique educational of space science and astrophysics will enable students to form mentoring relationships, and experience to students who want careers in give them a unique educational experience," these exciting fields. Dr Reid said. Details about the new degrees will be available "We expect interest in this new course to be at the University of Adelaide's Information very high." Day on Sunday, August 18, at the North Terrace campus. The new Bachelor of Science (Optics & Photonics) will not only provide an exciting The new Bachelor of Science (Space Science new career path in applied physics, but also and Astrophysics) aims to produce graduates help to address an expected shortfall in this that are well suited to careers in space and area of expertise in South Australia. astrophysical research. Photonics is the exploration and development Graduates are likely to follow career paths in a of the use of laser light in any endeavour, be it range of industries, putting into practice the scientific, technological, medical or artistic. -

J. Collins Malay Dialect Research in Malysia: the Issue of Perspective

J. Collins Malay dialect research in Malysia: The issue of perspective In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 145 (1989), no: 2/3, Leiden, 235-264 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/28/2021 12:15:07AM via free access JAMES T. COLLINS MALAY DIALECT RESEARCH IN MALAYSIA: THE ISSUE OF PERSPECTIVE1 Introduction When European travellers and adventurers began to explore the coasts and islands of Southeast Asia almost five hundred years ago, they found Malay spoken in many of the ports and entrepots of the region. Indeed, today Malay remains an important indigenous language in Malaysia, Indonesia, Brunei, Thailand and Singapore.2 It should not be a surprise, then, that such a widespread and ancient language is characterized by a wealth of diverse 1 Earlier versions of this paper were presented to the English Department of the National University of Singapore (July 22,1987) and to the Persatuan Linguistik Malaysia (July 23, 1987). I would like to thank those who attended those presentations and provided valuable insights that have contributed to improving the paper. I am especially grateful to Dr. Anne Pakir of Singapore and to Dr. Nik Safiah Karim of Malaysia, who invited me to present a paper. I am also grateful to Dr. Azhar M. Simin and En. Awang Sariyan, who considerably enlivened the presentation in Kuala Lumpur. Professor George Grace and Professor Albert Schiitz read earlier drafts of this paper. I thank them for their advice and encouragement. 2 Writing in 1881, Maxwell (1907:2) observed that: 'Malay is the language not of a nation, but of tribes and communities widely scattered in the East.. -

Tragic Orphans: Indians in Malaysia

BIBLIOGRAPHY Abdul Rahman Putra Al-Haj, Tunku. Looking Back: The Historic Years of Malaya and Malaysia. Kuala Lumpur: Pustaka Antara, 1977. ———. Viewpoints. Kuala Lumpur: Heinemann Educational Books (Asia), 1978. Abdul Rashid Moten. “Modernization and the Process of Globalization: The Muslim Experience and Responses”. In Islam in Southeast Asia: Political, Social and Strategic Challenges for the 21st Century, edited by K.S. Nathan and Mohammad Hashim Kamali. Singapore: Institute for Southeast Asian Studies, 2005. Abraham, Collin. “Manipulation and Management of Racial and Ethnic Groups in Colonial Malaysia: A Case Study of Ideological Domination and Control”. In Ethnicity and Ethnic Relations in Malaysia, edited by Raymond L.M. Lee. Illinois: Northern Illinois University, Center for Southeast Asian Studies, 1986. ———. The Naked Social Order: The Roots of Racial Polarisation in Malaysia. Subang Jaya: Pelanduk, 2004 (1997). ———. “The Finest Hour”: The Malaysian-MCP Peace Accord in Perspective. Petaling Jaya: Strategic Information and Research Development Centre, 2006. Abu Talib Ahmad. “The Malay Community and Memory of the Japanese Occupation”. In War and Memory in Malaysia and Singapore, edited by Patricia Lim Pui Huen and Diana Wong. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2000. ———. The Malay Muslims, Islam and the Rising Sun: 1941–1945. Kuala Lumpur: MBRAS, 2003. Ackerman, Susan E. and Raymond L.M. Lee. Heaven in Transition: Innovation and Ethnic Identity in Malaysia. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1988. Aeria, Andrew. “Skewed Economic Development and Inequality: The New Economic Policy in Sarawak”. In The New Economic Policy in Malaysia: Affirmative Action, Ethnic Inequalities and Social Justice, edited by Edmund Terence Gomez and Johan Saravanamuttu. -

An Examination of Regional Views on South Asian Co-Operation with Special Reference to Development and Security Perspectives in India and Shri Lanka

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 Northi Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. -

Journal of Family Issues

Journal of Family Issues http://jfi.sagepub.com/ Ethnic Identity Formation During Adolescence: The Critical Role of Families Adriana J. Umaña-Taylor, Ruchi Bhanot and Nana Shin Journal of Family Issues 2006 27: 390 DOI: 10.1177/0192513X05282960 The online version of this article can be found at: http://jfi.sagepub.com/content/27/3/390 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Journal of Family Issues can be found at: Email Alerts: http://jfi.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://jfi.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://jfi.sagepub.com/content/27/3/390.refs.html >> Version of Record - Jan 31, 2006 What is This? Downloaded from jfi.sagepub.com at SRI INTERNATIONAL LIBRARY on March 20, 2014 Journal of Family Issues Volume 27 Number 3 10.1177/0192513X05282960JournalUmaña-Taylor of Family et al. Issues / Ethnic Identity and the Role of Families March 2006 390-414 © 2006 Sage Publications 10.1177/0192513X05282960 Ethnic Identity Formation http://jfi.sagepub.com hosted at During Adolescence http://online.sagepub.com The Critical Role of Families Adriana J. Umaña-Taylor Arizona State University Ruchi Bhanot Nana Shin University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign An ecological model of ethnic identity was examined among 639 adolescents of Asian Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Vietnamese, and Salvadoran descent. Using structural equation modeling and, specifically, multiple group compari- sons, findings indicated that familial ethnic socialization (FES) played a sig- nificant role in the process of ethnic identity formation for all adolescents, regardless of ethnic background. -

The Malay Language 'Pantun' of Melaka Chetti Indians in Malaysia

International Journal of Comparative Literature & Translation Studies ISSN: 2202-9451 www.ijclts.aiac.org.au The Malay Language ‘Pantun’ of Melaka Chetti Indians in Malaysia: Malay Worldview, Lived Experiences and Hybrid Identity Airil Haimi Mohd Adnan*, Indrani Arunasalam Sathasivam Pillay Academy of Language Studies,, Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM) Perak Branch, Seri Iskandar Campus, 32610 State of Perak, Malaysia Corresponding Author: Airil Haimi Mohd Adnan, E-mail: [email protected] ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history The Melaka Chetti Indians are a small community of ‘peranakan’ (Malay meaning ‘locally born’) Received: January 26, 2020 people in Malaysia. The Melaka Chettis are descendants of traders from the Indian subcontinent Accepted: March 21, 2020 who married local women, mostly during the time of the Melaka Malay Empire from the 1400s Published: April 30, 2020 to 1500s. The Melaka Chettis adopted the local lingua franca ‘bahasa Melayu’ or Malay as Volume: 8 Issue: 2 their first language together with the ‘adat’ (Malay meaning ‘customs’) of the Malay people, their traditional mannerisms and also their literary prowess. Not only did the Melaka Chettis successfully adopted the literary traditions of the Malay people, they also adapted these arts Conflicts of interest: None forms to become part of their own unique hybrid identities based on their worldviews and lived Funding: This empirical research proj- experiences within the Malay Peninsula or more famously known as the Golden Chersonese / ect was made possible by the -

Indonesian, Malaysian and Thai Secondary School Students' Willingness to Communicate in English

Malaysian Journal of Learning and Instruction: Vol. 17 (No. 1) January 2020: 1-24 1 How to cite this article: Tan, K. E., Ng., M. L. Y., Abdullah, A., Ahmad, N., Phairot, E., Jawas, U., & Liskinasih, A. (2020). Indonesian, Malaysian and Thai secondary school students’ willingness to communicate in English. Malaysian Journal of Learning & Instruction, 17(1), 1-24 INDONESIAN, MALAYSIAN AND THAI SECONDARY SCHOOL STUDENTS’ WILLINGNESS TO COMMUNICATE IN ENGLISH 1Kok-Eng Tan, 2Melissa Ng Lee Yen Abdullah, 3Amelia Abdullah, 4Norlida Ahmad, 5Ekkapon Phairot, 6Umiati Jawas & 7Ayu Liskinasih 1-4 School of Educational Studies, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Malaysia 5Songkhla Rajabhat University, Thailand 6-7Department of English Language and Literature Universitas Kanjuruhan Malang, Indonesia 1Corresponding author: [email protected] Received: 6/9/2018 Revised: 14/7/2019 Accepted: 10/11/2019 Published: 31/1/2020 ABSTRACT Purpose – This quantitative study explored willingness to communicate (WTC) across two settings, ESL in Malaysia, and EFL in Indonesia and Thailand. Participants’ WTC levels were measured and communicative situations in which participants were almost always willing and almost never willing to communicate in English were identified. Method – Convenience sampling was used to select the three countries, four secondary schools and 42 intact classes from Years 7 to 10. Two schools were in Malaysia, while one school each was in Indonesia and Thailand. A total of 1038 participants, consisting of 291 Malaysians, 325 Indonesians and 422 Thais took part in the study. The instrument used was an adapted questionnaire measuring WTC inside and outside the English classroom. 2 Malaysian Journal of Learning and Instruction: Vol. -

A Sociolinguistics Study on the Use of the Javanese Language in the Learning Process in Primary Schools in Surakarta, Central Java, Indonesia

International Education Studies; Vol. 7, No. 6; 2014 ISSN 1913-9020 E-ISSN 1913-9039 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education A Sociolinguistics Study on the Use of the Javanese Language in the Learning Process in Primary Schools in Surakarta, Central Java, Indonesia Kundharu Saddhono1 & Muhammad Rohmadi1 1 Sebelas Maret University, Indonesia Correspondence: Kundharu Saddhono, Sebelas Maret University, Jl. Ir. Sutami 36 Surakarta, Indonesia. E-mail: [email protected] Received: February 24, 2014 Accepted: April 8, 2014 Online Published: May 20, 2014 doi:10.5539/ies.v7n6p25 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ies.v7n6p25 Abstract This study aims at describing the use of language at primary schools grade 1, 2, and 3 in Surakarta. The study belongs to descriptive qualitative research. It emphasizes in a note which depict real situation to support data presentation. Content analysis is used as research methodology. It analyzes the research result of the observed speech event. The data are collected from three sources: informant, events, and documents. Results of the study demonstrate that the use of Javanese language is still dominant in the learning process at primary schools in Surakarta. Many factors affect the use of Javanese language as mother tongue in classroom teaching-learning process. They are (1) balancing the learning process, so that learners are able to better understand the material presented by the teacher (2) teacher’s habit to speak Javanese language, and (3) drawing student’s attention. The factors underlying this phenomenon are explained by teacher and student’s lack of Indonesian language vocabulary. In addition, there is an element unnoticed by teachers. -

Learn Thai Language in Malaysia

Learn thai language in malaysia Continue Learning in Japan - Shinjuku Japan Language Research Institute in Japan Briefing Workshop is back. This time we are with Shinjuku of the Japanese Language Institute (SNG) to give a briefing for our students, on learning Japanese in Japan.You will not only learn the language, but you will ... Or nearby, the Thailand- Malaysia border. Almost one million Thai Muslims live in this subregion, which is a belief, and learn how, to grow other (besides rice) crops for which there is a good market; Thai, this term literally means visitor, ASEAN identity, are we there yet? Poll by Thai Tertiary Students ' Sociolinguistic. Views on the ASEAN community. Nussara Waddsorn. The Assumption University usually introduces and offers as a mandatory optional or free optional foreign language course in the state-higher Japanese, German, Spanish and Thai languages of Malaysia. In what part students find it easy or difficult to learn, taking Mandarin READING HABITS AND ATTITUDES OF THAI L2 STUDENTS from MICHAEL JOHN STRAUSS, presented partly to meet the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS (TESOL) I was able to learn Thai with Sukothai, where you can learn a lot about the deep history of Thailand and culture. Be sure to read the guide and learn a little about the story before you go. Also consider visiting neighboring countries like Cambodia, Vietnam and Malaysia. Air LANGUAGE: Thai, English, Bangkok TYPE OF GOVERNMENT: Constitutional Monarchy CURRENCY: Bath (THB) TIME ZONE: GMT No 7 Thailand invites you to escape into a world of exotic enchantment and excitement, from the Malaysian peninsula. -

Identity and Language of Tamil Community in Malaysia: Issues and Challenges

DOI: 10.7763/IPEDR. 2012. V48. 17 Identity and Language of Tamil Community in Malaysia: Issues and Challenges + + + M. Rajantheran1 , Balakrishnan Muniapan2 and G. Manickam Govindaraju3 1Indian Studies Department, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 2Swinburne University of Technology, Sarawak, Malaysia 3School of Communication, Taylor’s University, Subang Jaya, Malaysia Abstract. Malaysia’s ruling party came under scrutiny in the 2008 general election for the inability to resolve pressing issues confronted by the minority Malaysian Indian community. Some of the issues include unequal distribution of income, religion, education as well as unequal job opportunity. The ruling party’s affirmation came under critical situation again when the ruling government decided against recognising Tamil language as a subject for the major examination (SPM) in Malaysia. This move drew dissatisfaction among Indians, especially the Tamil community because it is considered as a move to destroy the identity of Tamils. Utilising social theory, this paper looks into the fundamentals of the language and the repercussion of this move by Malaysian government and the effect to the Malaysian Indians identity. Keywords: Identity, Tamil, Education, Marginalisation. 1. Introduction Concepts of identity and community had been long debated in the arena of sociology, anthropology and social philosophy. Every community has distinctive identities that are based upon values, attitudes, beliefs and norms. All identities emerge within a system of social relations and representations (Guibernau, 2007). Identity of a community is largely related to the race it represents. Race matters because it is one of the ways to distinguish and segregate people besides being a heated political matter (Higginbotham, 2006). -

REVIEWING LEXICOLOGY of the NUSANTARA LANGUAGE Mohd Yusop Sharifudin Universiti Putra Malaysia Email

Journal of Malay Islamic Studies Vol. 2 No. 1 June 2018 REVIEWING LEXICOLOGY OF THE NUSANTARA LANGUAGE Mohd Yusop Sharifudin Universiti Putra Malaysia Email: [email protected] Abstract The strength of a language is its ability to reveal all human behaviour and progress of civilization. Language should be ready for use at all times and in any human activity and must be able to grow together with all forms of discipline and knowledge. Languages that are not dynamic over time will become obsolete, archaic and finally extinct. Accordingly, the effort to develop and create a civilisation needs to take into account also the effort to expand its language as the medium of instruction. The most basic language development in this regard was to look for vocabulary that could potentially be taken to develope a dynamic language. This paper shows the potential and the wealth of lexical resources in building the Nusantara language to become a world language. Keywords: Lexicology, Nusantara Language Introduction Language is an important means for humans to communicate and build interaction. Language is basically a means of communication within community members. Communication takes place not only verbally, but also in writing (Sirbu 2015, 405). language is also a tool that shows the level of civilization in humans (Holtgraves et al. 2014, 230). In order to play an important role as a means of developing civilization, language must continue to develop dynamically over time and enriched according to the needs and development of civilization. Likewise the case with Nusantara Malay language. This paper aims to describe how to develop Nusantara Malay language through the development of various Malay vocabularies. -

September 2009 Special Edition Language, Culture and Identity in Asia

The Linguistics Journal – September 2009 The Linguistics Journal September 2009 Special Edition Language, Culture and Identity in Asia Editors: Francesco Cavallaro, Andrea Milde, & Peter Sercombe The Linguistics Journal – Special Edition Page 1 The Linguistics Journal – September 2009 The Linguistics Journal September 2009 Special Edition Language, Culture and Identity in Asia Editors: Francesco Cavallaro, Andrea Milde, & Peter Sercombe The Linguistics Journal: Special Edition Published by the Linguistics Journal Press Linguistics Journal Press A Division of Time Taylor International Ltd Trustnet Chambers P.O. Box 3444 Road Town, Tortola British Virgin Islands http://www.linguistics-journal.com © Linguistics Journal Press 2009 This E-book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of the Linguistics Journal Press. No unauthorized photocopying All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of The Linguistics Journal. [email protected] Editors: Francesco Cavallaro, Andrea Milde, & Peter Sercombe Senior Associate Editor: Katalin Egri Ku-Mesu Journal Production Editor: Benjamin Schmeiser ISSN 1738-1460 The Linguistics Journal – Special Edition Page 2 The Linguistics Journal – September 2009 Table of Contents Foreword by Francesco Cavallaro, Andrea Milde, & Peter Sercombe………………………...... 4 - 7 1. Will Baker……………………………………………………………………………………… 8 - 35 -Language, Culture and Identity through English as a Lingua Franca in Asia: Notes from the Field 2. Ruth M.H. Wong …………………………………………………………………………….. 36 - 62 -Identity Change: Overseas Students Returning to Hong Kong 3. Jules Winchester……………………………………..………………………………………… 63 - 81 -The Self Concept, Culture and Cultural Identity: An Examination of the Verbal Expression of the Self Concept in an Intercultural Context 4.