The Agudás' Architecture on the Bight of Benin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Palace Sculptures of Abomey

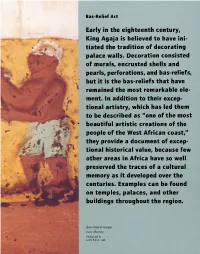

Bas-Relief Art Early in the eighteenth century, King Agaja is believed to have ini tiated the tradition of decorating palace walls. Decoration consisted of murals, encrusted shells and pearls, perfo rations, and bas-reliefs, , but it is the bas-reliefs that have remained the most remarkable ele ment. In addition to their excep tional artistry, which has led them to be described as "one of the most " beautiful artistic creations of the people of the West African coast, rr they provide a document of excep tional historical value, because few other areas in Africa have so well preserved the traces of a cultural · . memory as it developed over the centuries. Exa mples can be found on temples, palaces, and other buildings throughout the region. Bas-relief at temple near Abomey. Photograph by Leslie Railler, 1996. BAS-RELIEF ART 49 Commonly called noudide in Fon, from the root word meaning "to design" or "to portray," the bas-reliefs are three-dimensional, modeled- and painted earth pictograms. Early examples of the form, first in religious temples and then in the palaces, were more abstract than figurative. Gradually, figurative depictions became the prevalent style, illustrating the tales told by the kings' heralds and other Fon storytellers. Palace bas-reliefs were fashioned according to a long-standing tradition of The original earth architectural and sculptural renovation. used to make bas Ruling monarchs commissioned new palaces reliefs came from ter and artworks, as well as alterations of ear mite mounds such as lier ones, thereby glorifying the past while this one near Abomey. bringing its art and architecture up to date. -

Tapestry from Benin with Coats of Arms

TAPESTRY FROM BENIN WITH COATS OF ARMS - translated into English from Danish by Kristian Katholm Olsen - notes by Jørgen Olsen Genvej til Udvikling buys and sends forward tapestry of cotton with the coats of arms, which originally were used by the kings, who in the years from 1600 to 1900 ruled the area, which today is known as The Republic of Benin. http://gtu.dk/applikation_BENIN.jpg We buy the tapestry together with some other commodities of cotton and brass from Association des Femmes Amies, the Friendship Union of Women, AFA, which is closer described at http://www.emmaus-international.org/en/who-are-we/emmaus-around-the- world/africa/benin/a-f-a.html Margrethe Pallesen, ethnographer and gardener, who lived from 1956 until 2004, visited Benin in 1993, and was the first, who introduced the coat of arms - tapestries to GtU. Margrethe has written the following pages with a historic account, a directory of the kings and every single coat of arms as well as concluding remarks about Benin of 1994. TAPESTRY FROM BENIN DAHOMEY – AN AFRICAN KINGDOM In the country, which today goes by the name of Benin there once were a king of the Fon people, who was called Gangnihessou. When he died the realm was split between his two sons. One of them got the coast area. The other one, whose name was Dakodonou, got the inner parts of the country. Dakodonou would strengthen his kingdom and decided to conquer Abomey, which was ruled by King Da. Before he went to war he swore that he would kill King Da by tearing open his stomach. -

Getting to Know the K Umbukumbu Exhibition at the National Museum Brazil, 1818-2018

Getting to Know the K umbukumbu Exhibition at the National Museum Brazil, 1818-2018 Mariza de Carvalho Soares Michele de Barcelos Agostinho Rachel Corrêa Lima Getting to Know the K umbukumbu Exhibition at the National Museum Brazil, 1818-2018 Mariza de Carvalho Soares Michele de Barcelos Agostinho Rachel Corrêa Lima Slave Societies Digital Archive Press Nashville 2021 3 Publication of this book has been supported by grants from the Fundaçāo de Amparo à Pesquisa do Rio de Janeiro; the Museu Nacional/ Getting to Know Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro/Brazil; and the Slave Societies Digital Archive/Vanderbilt University. the K umbukumbu Originally published as: Conhecendo a exposição Kumbukumbu Exhibition at the do Museu Nacional (Rio de Janeiro: Museu Nacional, 2016). National Museum English edition copyright © 2021 Slave Societies Digital Archive Press Brazil, 1818-2018 ______________ Slave Societies Digital Archive Press 2301 Vanderbilt Pl., PMB 351802, Nashville, TN, 37235, United States Authors: Soares, Mariza de Carvalho, 1951; Agostinho, Michele de Barcelos, 1980; Lima, Rachel Correa, 1966. Title: Getting to Know the Kumbukumbu Exhibition at the National Museum, Brazil, 1818-2018 First Published 2021 Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978-0-578-91682-8 (cover photo) Street market. Aneho, Togo. 4 Photo by Milton Guran. 5 Project A New Room for the African Collection Director João Pacheco de Oliveira Curator Mariza de Carvalho Soares 6 7 Catalogue Team Research Mariza de Carvalho Soares Michele de Barcelos Agostinho Rachel Corrêa Lima Carolina Cabral Aline Chaves Rabelo Drawings Maurílio de Oliveira Photographs of the Collection Roosevelt Mota Graphic Design UMAstudio - Clarisse Sá Earp Translated by Cecília Grespan Edited by Kara D. -

A Journal of African Studies

UCLA Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies Title Reprint of Interview with Boniface I. Obichere: Biographical Studies of Dahomey's King Ghezo and America's Malcolm X Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3tm0k443 Journal Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies, 29(1) ISSN 0041-5715 Author n/a, n/a Publication Date 2002 DOI 10.5070/F7291016567 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Biographical Studies of Dahomey's King Ghezo and America's Malcolm X Reprint of Interview with Boniface I. Obichere (Imercom, 16:5 (I February 1994). 1-5.) Hisroriall Boniface Obichere describes his currellf research projects, which /OCI/S Ol/tll'O I'ery dijferem leaders who exerciud greal i,,/lll ellce illt"e;r times_ Obicher-e: 11le area ofmy work here is African history: I specialize in West African history. Al the moment I'm engaged in two research projects. the flJS1 ofwhich deals with the former kingdom of Dahomey (which was located in what is now southern Benin). I'm writing a biography of one of the most significant kings of the nineteenth century. Dahomey's King Ghezo. He ascended lhe throne in 1818 and ruled until 1858. which gave hinl a very long reign. His reign marked a high point ofpower and a turning point in the history ofthe kingdom. He compels my interest for several reasons. First. he lived to see the abolition of the slave trade. and he made his kingdom change from heavy economic reliance on the slave trade (0 legitimate trade in local products. -

Universidade Federal De São Paulo Escola De Filosofia, Letras E Ciências Humanas Danielle Yumi Suguiama O Daomé E Suas “Ama

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE SÃO PAULO ESCOLA DE FILOSOFIA, LETRAS E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS DANIELLE YUMI SUGUIAMA O DAOMÉ E SUAS “AMAZONAS” NO SÉCULO XIX: leituras a partir de Frederick E. Forbes e Richard F. Burton GUARULHOS 2019 DANIELLE YUMI SUGUIAMA O DAOMÉ E SUAS “AMAZONAS” NO SÉCULO XIX: leituras a partir de Frederick E. Forbes e Richard F. Burton Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- graduação à Universidade Federal de São Paulo para a obtenção do título de Mestre em História. Área de concentração: História Orientação: Prof. Dr. Jaime Rodrigues GUARULHOS 2019 Suguiama, Danielle Yumi. O Daomé e suas “amazonas” no século XIX : leituras a partir de Frederick E. Forbes e Richard F. Burton / Danielle Yumi Suguiama. Guarulhos, 2018. 167 f. Dissertação(Mestrado em História) – Universidade Federal de São Paulo, Escola de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas,2018. Orientação:Prof. Dr. Jaime Rodrigues. 1. Reino Daomé. 2. "Amazonas". 3.História da África. I.Jaime Rodrigues. II. Doutor. Danielle Yumi Suguiama O Daomé e suas “amazonas” no século XIX: leituras a partir de Frederick E. Forbes e Richard F. Burton Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- graduação à Universidade Federal de São Paulo para a obtenção do título de Mestre em História. Área de concentração: História Orientação: Prof. Dr. Jaime Rodrigues Aprovação: ____/____/________ Prof. Dr. Jaime Rodrigues Universidade Federal de São Paulo - EFLCH Prof. Dr. Alexsander Lemos de Almeida Gebara Universidade Federal Fluminense - UFF Profª. Drª. Patricia Teixeira Santos Universidade Federal de São Paulo - EFLCH Para Ricardo Shigueru, meu pai AGRADECIMENTOS O primeiro agradecimento se destina ao meu orientador, Prof. -

A Level History a African Kingdoms Ebook

Qualification Accredited A LEVEL EBook HISTORY A H105/H505 African Kingdoms: A Guide to the Kingdoms of Songhay, Kongo, Benin, Oyo and Dahomey c.1400 – c.1800 By Dr. Toby Green Version 1 A LEVEL HISTORY A AFRICAN KINGDOMS EBOOK CONTENTS Introduction: Precolonial West African 3 Kingdoms in context Chapter One: The Songhay Empire 8 Chapter Two: The Kingdom of the Kongo, 18 c.1400–c.1709 Chapter Three: The Kingdoms and empires 27 of Oyo and Dahomey, c.1608–c.1800 Chapter Four: The Kingdom of Benin 37 c.1500–c.1750 Conclusion 46 2 A LEVEL HISTORY A AFRICAN KINGDOMS EBOOK Introduction: Precolonial West African Kingdoms in context This course book introduces A level students to the However, as this is the first time that students pursuing richness and depth of several of the kingdoms of West A level History have had the chance to study African Africa which flourished in the centuries prior to the onset histories in depth, it’s important to set out both what of European colonisation. For hundreds of years, the is distinctive about African history and the themes and kingdoms of Benin, Dahomey, Kongo, Oyo and Songhay methods which are appropriate to its study. It’s worth produced exquisite works of art – illustrated manuscripts, beginning by setting out the extent of the historical sculptures and statuary – developed complex state knowledge which has developed over the last fifty years mechanisms, and built diplomatic links to Europe, on precolonial West Africa. Work by archaeologists, North Africa and the Americas. These kingdoms rose anthropologists, art historians, geographers and historians and fell over time, in common with kingdoms around has revealed societies of great complexity and global the world, along with patterns of global trade and local interaction in West Africa from a very early time. -

Dr. Suzanne Blier1 and William Haveman2 1 Professor of African and African American Studies, Harvard University 2 Harvard Extension School

Development of Abomey, capital of the former West African kingdom of Dahomey: Using GIS to identify spatial-temporal patterns Dr. Suzanne Blier1 and William Haveman2 1 Professor of African and African American Studies, Harvard University 2 Harvard Extension School Discussion •In the Danhomė Background language, Dan •Abomey was the royal capital of the kingdom of Dahomey (Danhomė) (Dangbe) is the word located in what is now the country of Benin in West Africa. for the powerful local •The kingdom was conquered by several kings including Huegbadja python god. •Another representation (1645-1685), Akaba (1685-1708), Agaja (1708-1740), Tegbesu (1740-1774), • Danhomė means “in of Dangbe in the design Kpengla (1774-1789), Agonglo (1789-1797), Adandozan (1797-1818), Guezo (1818-1858), and Glele (1858- 1889). the stomach of Dan”, of the city is the dry moat •As the city grew, stating that Danhomė around the center of the space was inhabitants reside in city (represented by the appropriated from the middle (within the dark black square on the indigenous Objective encircling circle) of the maps). inhabitants forcing •Analyze the urban development of Abomey for spatial-temporal powerful python god, •This represents the local residents away pattern: Dan/Dangbe. encircling python god from the palace. How did the city develop over time from one king’s reign to the Image of a bas-relief of Dangbe provided by •The appropriation of with the inhabitants in next? http://www.ecn.wfu.edu/~cottrell/benin/dia ry.html land in a counter- the center. •Determine how culture played a part in the city’s development: clockwise spiral pattern What role did cultural beliefs play in the design of the city? and the spiral form tail- •Examine how development practices changed over time: consuming python god Was there any changes in where development was concentrated Dan appear to be over time? evidently related. -

Abomeydepliant.Pdf

Capitale historique de l'ancien royaume du Danhomè, berceau du culte vaudou (vodun) et creu- set de la civilisation fon, Abomey est l'un des sites touristiques majeurs du Bénin. Le patrimoine exceptionnel de notre cité-palais reconnu par l’UNESCO est l'héritage vivant des ancêtres du peuple Fon. Les Aboméens en sont fiers, ils le protègent, le conservent et l'animent comme le plus précieux des biens. A leurs côtés, il me tient à coeur de valoriser cette ressource et d'y enraciner la force de demain. Abomey fait le pari du développement, c’est une ville qui gagne ! Blaise Onésiphore Ahanhanzo Glélé Maire d'Abomey, Président de l'Association Nationale des Communes du Bénin (ANCB) MI KUWABO ! Soyez les bienvenus ! e e Abomey est fondée au XVII siècle par le roi Houégbadja. Son fils, Akaba, r i bâtit son palais sur la dépouille du propriétaire des lieux, dénommé Dan et o t baptise le royaume Danhomè, signifiant littéralement en langue fon "dans le s i ventre de Dan". Entourée d'un fossé défensif, la cité prend le nom d'Agbomè h ' (en fon : "à l'intérieur du fossé"), qui donnera par dérivation "Abomey". C'est d le roi Houégbadja qui institue la culture religieuse et politique qui caractéri- u e sera le puissant royaume du Danhomè jusqu'à la colonisation française. p e n Au XVIII siècle, le roi Agadja forme un régiment d'amazones et étend le U royaume jusqu'à la côte Atlantique en conquérant les royaumes voisins d'Allada puis de Savi. Aux côtés du Portugal, de la France puis de la Hollande, le royaume du Danhomè participe alors pleinement au commerce des esclaves par le port de Ouidah et s'enrichit considérablement, mais il connaît des guerres répétées contre le royaume des yorubas. -

Redalyc.Aquele Que "Salva" a Mãe E O Filho

Tempo ISSN: 1413-7704 [email protected] Universidade Federal Fluminense Brasil Araujo, Ana Lucia Aquele que "salva" a mãe e o filho Tempo, vol. 15, núm. 29, 2010, pp. 43-66 Universidade Federal Fluminense Niterói, Brasil Disponível em: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=167016571003 Como citar este artigo Número completo Sistema de Informação Científica Mais artigos Rede de Revistas Científicas da América Latina, Caribe , Espanha e Portugal Home da revista no Redalyc Projeto acadêmico sem fins lucrativos desenvolvido no âmbito da iniciativa Acesso Aberto 29 • Tempo Aquele que “salva” a mãe e o filho* Ana Lucia Araujo** O artigo busca reconstruir o mito do mercador de escravos Francisco Félix de Souza (1754-1849). A partir de fontes textuais, entrevistas realizadas com membros da família e do exame do memorial de Francisco Félix de Souza, analisa-se a reconstrução da memória do mercador no seio da família. Ao mesmo tempo, tenta-se entender como a memória do ancestral exprime as implicações políticas associadas à memória da escravidão no Benim contemporâneo. Palavras-chave: memória, comércio atlântico de escravos, Francisco Félix de Souza The One Who Rescues the Mother and the Child This paper aims to reconstruct the myth surrounding the Brazilian slave merchant Francisco Félix de Souza (1754-1849). Relying on the exam of textual sources, inter- views with family members as well as the examination of Francisco Félix de Souza’s memorial, the article analyzes the reconstruction of the memory of the slave merchant within his family. At the same time, it aims at understanding how the memory of the ancestor expresses the political issues related to the memory of slavery in the contemporary Benin. -

Femmes Et Pouvoir Politique Au Benin Des Origines Dahomeennes a Nos Jours

FEMMES ET POUVOIR POLITIQUE AU BENIN DES ORIGINES DAHOMEENNES A NOS JOURS Marie-Odile ATTANASSO, 1 © FES, Bénin Les Cocotiers 08 B.P. 0620 Tri Postal Cotonou - Bénin Tél. : +229 21 30 27 89 / 21 30 28 84 Fax : +229 21 30 32 27 E-mail : [email protected] www.fes-benin.org Coordination : M. Rufin B. GODJO Caludia Y. Togbé Relecture, critique et correction : - M. Omer SASSE Dépot Légal N° 6732 du 13 / 06 / 2013 2ème Trimestre / Bibliothèque Nationale ISBN :978-99919-1-411-4 Mise en page et impression : Imprimerie COPEF (Cotonou - Bénin) 01 BP 2507 Tél. : 21 30 16 04 / 90 03 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] «Tout usage à but commercial des publications, brochures ou autres imprimés de la Frie- drich-Ebert-Stiftung est formellement interdit à moins d’une autorisation écrite délivrée préalablement par la Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung». 2 SOMMAIRE Liste des sigles et abréviations ............................................. 5 Liste des tableaux ..…………………………………………………….... 11 Liste des encadrés ………………………………………………….…… 14 AVANT PROPOS ..................................................................... 15 RESUME .................................................................................. 17 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................... 23 Chapitre I : Etat des lieux de la participation de la femme à la vie politique en Afrique et dans le monde ……………………….…. 27 I. Démarche méthodologique ........................................... 27 II. Les difficultés ............................................................... -

Front Cover September 12.Pmd

Volume 8, Number 2 September / Septembre 2012 The Superwomen of Ancient Dahomey: The World of the Amazons ANSELME GUEZO Les révolutions arabes: écrire des processus inachevés MUSTAPHA MEDJAHDI Africa, Japan and China SEIFUDEIN ADEM Aux origines du génocide rwandais SIDI MOHAMMED MOHAMMEDI The Afrikaners of South Africa – Settlers or Africans? ANTHONI VAN NIEUWKERK Quelles politiques pour rendre justice aux femmes africaines? BELKACEM BENZENINE ISSN: 0851-7592 Africa Review of Books / Revue africaine des Livres Editor/Editeur ARB Annual Subscription Rates / Tarifs d’abonnements annuels à la RAL Bahru Zewde (in US Dollar) (en dollars US) French Editor/Editeur Francophone Hassan Remaoun Africa Rest of the World Afrique Reste du monde Managing Editor Individual 10 15 Particuliers Asnake Kefale Institutional 15 20 Institutions Editorial Assistant/Assistante éditoriale Nadéra Benhalima Advertising Rates (in US Dollar) / Tarifs publicitaires (en dollars US) Text layout/Mise en page Size/Position Black & White Colour Format/emplacement Konjit Belete Noir & blanc Couleur Cartoon design / Artiste Inside front cover 2000 2800 Deuxième de couverture Elias Areda Back cover 1900 2500 Quatrième de couverture Full page 1500 2100 Page entière Three columns 1200 1680 Trois colonnes International Advisory Board / Comité éditorial international Two columns 900 1260 Deux colonnes Half page horizontal 900 1260 Demi-page horizontale Ama Ata Aidoo, Writer, Ghana Quarter page 500 700 Quart de page Tade Aina, Carnegie Corporation, New York One column 350 490 Une -

The Politics of Commercial Transition: Factional Conflict in Dahomey in the Context of the Ending of the Atlantic Slave Trade

Journal of African History, (), pp. –. Printed in the United Kingdom # Cambridge University Press THE POLITICS OF COMMERCIAL TRANSITION: FACTIONAL CONFLICT IN DAHOMEY IN THE CONTEXT OF THE ENDING OF THE ATLANTIC SLAVE TRADE University of Stirling}York University, Ontario* I , after a reign of forty years, King Gezo of Dahomey died and was succeeded by one of his sons called Badahun, who took the royal name of Glele by which he is more generally known. Badahun had been Gezo’s designated heir apparent for at least nine years prior to this but his accession to the throne was nevertheless challenged. The name Glele which he adopted alludes to these challenges, being according to Dahomian tradition ab- breviated from the aphorism Glelile ma nh oh nze, ‘You cannot take away a farm [gle]’, meaning that he would not allow anyone to appropriate the fruits of his labours, which is explained as expressing ‘his contempt for the attacks to which he had been exposed as heir apparent’." The fact that the succession to the throne was disputed on this occasion was, in itself, nothing unusual. Almost all royal successions in Dahomian history were contested among rival princes claiming the throne. Although the succession passed in principle to the king’s eldest son, this rule of primogeniture was qualified in two ways. First, the king might choose to set aside the claims of his eldest son if he was considered in any way unfit for the throne and designate as heir apparent another of his sons instead – as, indeed, had occurred in the case of Badahun himself.