The Politics of Commercial Transition: Factional Conflict in Dahomey in the Context of the Ending of the Atlantic Slave Trade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Palace Sculptures of Abomey

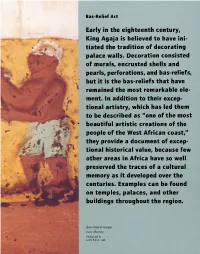

Bas-Relief Art Early in the eighteenth century, King Agaja is believed to have ini tiated the tradition of decorating palace walls. Decoration consisted of murals, encrusted shells and pearls, perfo rations, and bas-reliefs, , but it is the bas-reliefs that have remained the most remarkable ele ment. In addition to their excep tional artistry, which has led them to be described as "one of the most " beautiful artistic creations of the people of the West African coast, rr they provide a document of excep tional historical value, because few other areas in Africa have so well preserved the traces of a cultural · . memory as it developed over the centuries. Exa mples can be found on temples, palaces, and other buildings throughout the region. Bas-relief at temple near Abomey. Photograph by Leslie Railler, 1996. BAS-RELIEF ART 49 Commonly called noudide in Fon, from the root word meaning "to design" or "to portray," the bas-reliefs are three-dimensional, modeled- and painted earth pictograms. Early examples of the form, first in religious temples and then in the palaces, were more abstract than figurative. Gradually, figurative depictions became the prevalent style, illustrating the tales told by the kings' heralds and other Fon storytellers. Palace bas-reliefs were fashioned according to a long-standing tradition of The original earth architectural and sculptural renovation. used to make bas Ruling monarchs commissioned new palaces reliefs came from ter and artworks, as well as alterations of ear mite mounds such as lier ones, thereby glorifying the past while this one near Abomey. bringing its art and architecture up to date. -

Ketu (Benin) Ketu Is a Historical Region in What Is Now the Republic of Benin, in the Area of the Town of Kétou

Ketu (Benin) Ketu is a historical region in what is now the Republic of Benin, in the area of the town of Kétou (Ketu). It is one of the oldest capitals of the Yoruba speaking people, tracing its establishment to a settlement founded by a daughter of Oduduwa, also known as Odudua, Oòdua and Eleduwa. The regents of the town were traditionally styled "Alaketu", and are believed to be related to the Egba sub-group of the Yoruba people in present-day Nigeria. Ketu is considered one of the seven original kingdoms established by the children of Oduduwa in Oyo mythic history, though this ancient pedigree has been somewhat neglected in contemporary Yoruba historical research, which tends to focus on communities within Nigeria. The exact status of Ketu within the Oyo empire however is contested. Oyo sources claim Ketu as a dependency with claims that the Ketu paid an annual tribute and that its ruler attended the Bere festival in Oyo. In any case, there is no doubt that Ketu and Oyo maintained friendly relations largely due to their historical, linguistic, cultural and ethnic ties.[1] The kingdom was one of the main enemies of the ascendant kingdom of Dahomey, often fighting against Dahomeans as part of Oyo's imperial forces, but ultimately succumbing to the Fon in the 1880s as the kingdom was ravaged. A large number of Ketu's citizens were sold into slavery during these raids, which accounts for the kingdom's importance in Brazilian Candomblé. Ketu is often known as Queto in Portuguese orthography. Ewe connection Ewe traditions refer to Ketu as Amedzofe ("origin of humanity") or Mawufe ("home of the Supreme Being"). -

Oja Representational Objects in Yewaland, Ogun State, Nigeria Ayedun Matthew Kolawole Ab

African Scholar VOL. 18 NO. 6 Publications & ISSN: 2110-2086 Research SEPTEMBER, 2020 International African Scholar Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences (JHSS-6) Study of Forms and Functions of Esu – Oja Representational Objects in Yewaland, Ogun State, Nigeria Ayedun Matthew Kolawole Fine and Applied Arts Department, School of Vocational and Technical Education, Tai Solarin College of Education, Omu – Ijebu Abstract The representational images such as pots, rattles, bracelets, stones, cutlasses, wooden combs, staffs, mortals, brooms, etc. are religious and its significance for the worshippers were that they had faith in it. The denominator in the worship of all gods and spirits everywhere is faith. The power of an image was believed to be more real than that of a living being. The Yoruba appear to be satisfied with the gods with whom they are in immediate touch because they believe that when the Orisa have been worshipped, they will transmit what is necessary to Olodumare. This paper examines the traditional practices of the people of Yewa and discovers why Esu is market appellate. It focuses on the classifications of the forms and functions of Esu-Oja representational objects in selected towns in Yewaland. Keywords: appellate, classifications, divinities, fragment, forms, images, libations, mystical powers, Olodumare, representational, sacred, sacrifices, shrine, spirit archetype, transmission and transformation. Introduction Yewa which was formally called there are issues of intra-regional “Egbado” is located on Nigeria’s border conflicts that call for urgent attention. with the Republic of Benin. Yewa claim The popular decision to change the common origin from Ile-Ife, Oyo, ketu, Egbado name according to Asiwaju and Benin. -

« Palais Royaux D'abomey » (Benin)

« PALAIS ROYAUX D’ABOMEY » (BENIN) RAPPORT MISSION CONJOINTE DE SUIVI REACTIF CENTRE DU PATRIMOINE MONDIAL/ICOMOS/ICCROM DU 18 AU 22 AVRIL 2016 Sommaire REMERCIEMENTS .............................................................................................................................................. 4 Résumé et recommandations .......................................................................................................................... 5 I. ANTECEDENTS DE LA MISSION .................................................................................................................. 9 1.1. Historique ...................................................................................................................................... 9 1.2. Critère d’inscription sur la Liste du patrimoine mondial .......................................................... 10 1.3. Menaces pesant sur l’authenticité, soulevées dans le rapport d’évaluation de l’ICOMOS au moment de l’inscription .............................................................................................................. 12 1.4. Retrait du bien de la Liste du patrimoine mondial en péril ....................................................... 13 1.5. Examen de l’état de conservation par le Comité du patrimoine mondial ................................ 14 1.6. Justification de la mission ........................................................................................................... 15 1.7. Composition de la mission ......................................................................................................... -

Land Accessibility Characteristics Among Migrants in Yewa North Local Government Area of Ogun State, Nigeria

Asian Research Journal of Arts & Social Sciences 2(1): 1-12, 2017; Article no.ARJASS.30086 SCIENCEDOMAIN international www.sciencedomain.org Land Accessibility Characteristics among Migrants in Yewa North Local Government Area of Ogun State, Nigeria Gbenga John Oladehinde 1* , Kehinde Popoola 1, Afolabi Fatusin 2 and Gideon Adeyeni 1 1Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Osun State Nigeria. 2Department of Geography and Planning Sciences, Adekunle Ajasin University, Akungba-Akoko, Ondo State, Nigeria. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out collaboratively by all authors. Author GJO designed the study and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Authors KP and AF supervised the preparation of the first draft of the manuscript and managed the literature searches while author GA led and managed the data analyses. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/ARJASS/2017/30086 Editor(s): (1) Raffaela Giovagnoli, Pontifical Lateran University, Piazza San Giovanni in Laterano 4, Rome, Italy. (2) Sheying Chen, Social Policy and Administration, Pace University, New York, USA. Reviewers: (1) F. Famuyiwa, University of Lagos, Nigeria. (2) Lusugga Kironde, Ardhi University, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sciencedomain.org/review-history/17570 Received 16 th October 2016 Accepted 14 th January 2017 Original Research Article st Published 21 January 2017 ABSTRACT Aim: The study investigated challenges of land accessibility among migrants in Yewa North Local Government Area of Ogun State, Nigeria. Methodology: Data were obtained through questionnaire administration on a Migrant household head. Multistage sampling technique was used for selection of 161 respondents for the study. -

KETU MYTHS and the STATUS of WOMEN: a Structural Interpretation

NEXUS 8:1 (1990) 47 KETU MYTHS AND THE STATUS OF WOMEN: A Structural Interpretation Emmanuel Babatunde University of Lagos, Nigeria ABSTRACT Modern literature on the status of Yoruba women of South Western Nigeria has corrected the view that Yoruba women were suppressed, by throwing into relief areas of their prominence. B. Awe has drawn attention to the prominent part women like Iyalode played in traditional Yoruba politics (1977, 1979). J.A. Atanda (1979) and S.O. Babayemi (1979) have stressed the significant roles of women in the palace organization of Oyo. N. Sudarka (1973) and Karanja (1980) have explored the interesting area of Yoruba market women, showing that the economic strength which such economic enterprises confer made Yoruba women not only prominent but independent. Karanja, on the other hand, accepted that although economic enterprise brought a considerable measure of strength and prominence to the Yoruba woman, her relationship with her husband may not be interpreted as one marked with complete independence. In drawing attention to the role of women as mothers and as occupiers of the innermost and sacrosanct space within Yoruba domains, H. Callaway has demonstrated the importance of Yoruba women to central features of Yoruba society (1978). In this present work I discuss some Yoruba myths in order to throw into relief the prominence of women. RESUME La literature recente concernant I'etat des femmes Yoruba au sud ouest du Niger a corrige I'impression que les femmes Yoruba sont suppressees, en iIIuminant leur proeminence dans plusieurs aspects sociaux. B. Awe a demontre I'importance des femmes telle que Iyalode dans Ie domaine politique traditionnel (1977, 1979). -

African Concepts of Energy and Their Manifestations Through Art

AFRICAN CONCEPTS OF ENERGY AND THEIR MANIFESTATIONS THROUGH ART A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Renée B. Waite August, 2016 Thesis written by Renée B. Waite B.A., Ohio University, 2012 M.A., Kent State University, 2016 Approved by ____________________________________________________ Fred Smith, Ph.D., Advisor ____________________________________________________ Michael Loderstedt, M.F.A., Interim Director, School of Art ____________________________________________________ John R. Crawford-Spinelli, D.Ed., Dean, College of the Arts TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES………………………………………….. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS …………………………………… vi CHAPTERS I. Introduction ………………………………………………… 1 II. Terms and Art ……………………………………………... 4 III. Myths of Origin …………………………………………. 11 IV. Social Structure …………………………………………. 20 V. Divination Arts …………………………………………... 30 VI. Women as Vessels of Energy …………………………… 42 VII. Conclusion ……………………………………….…...... 56 VIII. Images ………………………………………………… 60 IX. Bibliography …………………………………………….. 84 X. Further Reading ………………………………………….. 86 iii LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1: Porogun Quarter, Ijebu-Ode, Nigeria, 1992, Photograph by John Pemberton III http://africa.si.edu/exhibits/cosmos/models.html. ……………………………………… 60 Figure 2: Yoruba Ifa Divination Tapper (Iroke Ifa) Nigeria; Ivory. 12in, Baltimore Museum of Art http://www.artbma.org/. ……………………………………………… 61 Figure 3.; Yoruba Opon Ifa (Divination Tray), Nigerian; carved wood 3/4 x 12 7/8 x 16 in. Smith College Museum of Art, http://www.smith.edu/artmuseum/. ………………….. 62 Figure 4. Ifa Divination Vessel; Female Caryatid (Agere Ifa); Ivory, wood or coconut shell inlay. Nigeria, Guinea Coast The Metropolitan Museum of Art, http://www.metmuseum.org. ……………………… 63 Figure 5. Beaded Crown of a Yoruba King. Nigerian; L.15 (crown), L.15 (fringe) in. -

Tapestry from Benin with Coats of Arms

TAPESTRY FROM BENIN WITH COATS OF ARMS - translated into English from Danish by Kristian Katholm Olsen - notes by Jørgen Olsen Genvej til Udvikling buys and sends forward tapestry of cotton with the coats of arms, which originally were used by the kings, who in the years from 1600 to 1900 ruled the area, which today is known as The Republic of Benin. http://gtu.dk/applikation_BENIN.jpg We buy the tapestry together with some other commodities of cotton and brass from Association des Femmes Amies, the Friendship Union of Women, AFA, which is closer described at http://www.emmaus-international.org/en/who-are-we/emmaus-around-the- world/africa/benin/a-f-a.html Margrethe Pallesen, ethnographer and gardener, who lived from 1956 until 2004, visited Benin in 1993, and was the first, who introduced the coat of arms - tapestries to GtU. Margrethe has written the following pages with a historic account, a directory of the kings and every single coat of arms as well as concluding remarks about Benin of 1994. TAPESTRY FROM BENIN DAHOMEY – AN AFRICAN KINGDOM In the country, which today goes by the name of Benin there once were a king of the Fon people, who was called Gangnihessou. When he died the realm was split between his two sons. One of them got the coast area. The other one, whose name was Dakodonou, got the inner parts of the country. Dakodonou would strengthen his kingdom and decided to conquer Abomey, which was ruled by King Da. Before he went to war he swore that he would kill King Da by tearing open his stomach. -

Patrimoine Culinaire Et Religieux Dans Le Vodoun De Ouidah, Bénin Rosa Nallely Moreno Moncayo

Le maïs mésoaméricain : patrimoine culinaire et religieux dans le vodoun de Ouidah, Bénin Rosa Nallely Moreno Moncayo To cite this version: Rosa Nallely Moreno Moncayo. Le maïs mésoaméricain : patrimoine culinaire et religieux dans le vodoun de Ouidah, Bénin. Anthropologie sociale et ethnologie. Université Paris sciences et lettres, 2019. Français. NNT : 2019PSLEP001. tel-02636827 HAL Id: tel-02636827 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-02636827 Submitted on 27 May 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THÈSE DE DOCTORAT de l’Université de recherche Paris Sciences et Lettres PSL Research University Préparée à l’École Pratique des Hautes Études Le maïs mésoaméricain : patrimoine culinaire et religieux dans le vodoun de Ouidah, Bénin. École doctorale de l’EPHE – ED 472 Spécialité : Anthropologie COMPOSITION DU JURY : M Serge BAHUCHET Professeur CE Président du jury Mme Isabelle BIANQUIS Professeur d’anthropologie Rapporteur Mme Emmanuelle Kadya TALL Chargée de recherche HDR Examinateur Soutenue par : Rosa Nallely MORENO MONCAYO le 11 -

Yoruba Culture of Nigeria: Creating Space for an Endangered Specie

ISSN 1712-8358[Print] Cross-Cultural Communication ISSN 1923-6700[Online] Vol. 9, No. 4, 2013, pp. 23-29 www.cscanada.net DOI:10.3968/j.ccc.1923670020130904.2598 www.cscanada.org Yoruba Culture of Nigeria: Creating Space for an Endangered Specie Adepeju Oti[a],*; Oyebola Ayeni[b] [a]Ph.D, Née Aderogba. Lead City University, Ibadan, Nigeria. [b] INTRODUCTION Ph.D. Lead City University, Ibadan, Nigeria. *Corresponding author. Culture refers to the cumulative deposit of knowledge, experience, beliefs, values, attitudes, meanings, Received 16 March 2013; accepted 11 July 2013 hierarchies, religion, notions of time, roles, spatial relations, concepts of the universe, and material objects Abstract and possessions acquired by a group of people in the The history of colonisation dates back to the 19th course of generations through individual and group Century. Africa and indeed Nigeria could not exercise striving (Hofstede, 1997). It is a collective programming her sovereignty during this period. In fact, the experience of the mind that distinguishes the members of one group of colonisation was a bitter sweet experience for the or category of people from another. The position that continent of Africa and indeed Nigeria, this is because the ideas, meanings, beliefs and values people learn as the same colonialist and explorers who exploited the members of society determines human nature. People are African and Nigerian economy; using it to develop theirs, what they learn, therefore, culture ultimately determine the quality in a person or society that arises from a were the same people who brought western education, concern for what is regarded as excellent in arts, letters, modern health care, writing and recently technology. -

Getting to Know the K Umbukumbu Exhibition at the National Museum Brazil, 1818-2018

Getting to Know the K umbukumbu Exhibition at the National Museum Brazil, 1818-2018 Mariza de Carvalho Soares Michele de Barcelos Agostinho Rachel Corrêa Lima Getting to Know the K umbukumbu Exhibition at the National Museum Brazil, 1818-2018 Mariza de Carvalho Soares Michele de Barcelos Agostinho Rachel Corrêa Lima Slave Societies Digital Archive Press Nashville 2021 3 Publication of this book has been supported by grants from the Fundaçāo de Amparo à Pesquisa do Rio de Janeiro; the Museu Nacional/ Getting to Know Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro/Brazil; and the Slave Societies Digital Archive/Vanderbilt University. the K umbukumbu Originally published as: Conhecendo a exposição Kumbukumbu Exhibition at the do Museu Nacional (Rio de Janeiro: Museu Nacional, 2016). National Museum English edition copyright © 2021 Slave Societies Digital Archive Press Brazil, 1818-2018 ______________ Slave Societies Digital Archive Press 2301 Vanderbilt Pl., PMB 351802, Nashville, TN, 37235, United States Authors: Soares, Mariza de Carvalho, 1951; Agostinho, Michele de Barcelos, 1980; Lima, Rachel Correa, 1966. Title: Getting to Know the Kumbukumbu Exhibition at the National Museum, Brazil, 1818-2018 First Published 2021 Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978-0-578-91682-8 (cover photo) Street market. Aneho, Togo. 4 Photo by Milton Guran. 5 Project A New Room for the African Collection Director João Pacheco de Oliveira Curator Mariza de Carvalho Soares 6 7 Catalogue Team Research Mariza de Carvalho Soares Michele de Barcelos Agostinho Rachel Corrêa Lima Carolina Cabral Aline Chaves Rabelo Drawings Maurílio de Oliveira Photographs of the Collection Roosevelt Mota Graphic Design UMAstudio - Clarisse Sá Earp Translated by Cecília Grespan Edited by Kara D. -

A Journal of African Studies

UCLA Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies Title Reprint of Interview with Boniface I. Obichere: Biographical Studies of Dahomey's King Ghezo and America's Malcolm X Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3tm0k443 Journal Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies, 29(1) ISSN 0041-5715 Author n/a, n/a Publication Date 2002 DOI 10.5070/F7291016567 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Biographical Studies of Dahomey's King Ghezo and America's Malcolm X Reprint of Interview with Boniface I. Obichere (Imercom, 16:5 (I February 1994). 1-5.) Hisroriall Boniface Obichere describes his currellf research projects, which /OCI/S Ol/tll'O I'ery dijferem leaders who exerciud greal i,,/lll ellce illt"e;r times_ Obicher-e: 11le area ofmy work here is African history: I specialize in West African history. Al the moment I'm engaged in two research projects. the flJS1 ofwhich deals with the former kingdom of Dahomey (which was located in what is now southern Benin). I'm writing a biography of one of the most significant kings of the nineteenth century. Dahomey's King Ghezo. He ascended lhe throne in 1818 and ruled until 1858. which gave hinl a very long reign. His reign marked a high point ofpower and a turning point in the history ofthe kingdom. He compels my interest for several reasons. First. he lived to see the abolition of the slave trade. and he made his kingdom change from heavy economic reliance on the slave trade (0 legitimate trade in local products.