Oja Representational Objects in Yewaland, Ogun State, Nigeria Ayedun Matthew Kolawole Ab

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Exodus and Identity Formation in View of the Yoruba Origin and Migration Narratives1

http://scriptura.journals.ac.za Scriptura 108 (2011), pp. 342-356 THE EXODUS AND IDENTITY FORMATION IN VIEW OF THE YORUBA ORIGIN AND MIGRATION NARRATIVES1 Funlola Olojede Old and New Testament Stellenbosch University The past is but the beginning of a beginning (HG Wells) Abstract Certain elements of the origin and migration narratives of the Yoruba such as a common ancestor, common ancestral home, common belief in the Supreme Deity provide a basis for identity formation and recognition among the people. It is argued that the narratives help to bring to light the memories of the Exodus and Israel’s recollection of Yahweh as the root of its identity. The juxtaposition of cosmogonic myths and migration theories foregrounds the elements of identity formation of the Yoruba people and have a parallel in the blending of both cosmic and migration elements in Exodus 14-15:18. This blending also points out clearly the role of Yahweh as the main character in the Sea event. Key Words: Exodus, Identity, Migration, Yahweh, Yorùbá Introduction The hypothesis is that Yorùbá traditions of origin and migration influence the process of identity formation in certain ways and that this implication for identity may contain certain heuristic values that can be used to interpret the exodus in a contextual way. In what follows, a literature review of basic cosmogonic myths and migration theories of the Yorùbá is carried out to determine their impact on the people’s identity formation. This is followed by a brief literary consideration of the Sea event (Exod 14-15) which is a two-way prosaic and poetic rendition of the sea crossing by the children of Israel after their departure from Egypt. -

P Hytopl Tid Lankto Al Cree N Com Ek

Vol. 6(11), pp. 373-388, December, 2014 DOI: 10.5897/JENE2014. 0473 Article number:EEB403248860 ISSN 2006-9847 Journal of Ecology and the Natural Environment Copyright © 2014 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http:://www.academicjournals.org/JENE Full Length Research Paper Phytoplankton composition and water chemistry of a tidal creek (Ipa-Itako) part of Lagos Lagoon Taofikat Abosede Adesalu*, Tolulope Adesanya and Chinwe Jessica Ogwuzor Department of Botany, University of Lagos, Akoka, Lagos, Lagos State, Nigeria. Received 10 September, 2014; Accepted 24 October, 2014 The composition and diversity of planktonic algae in a sluggish tidal freshwater/brackish mangrove dominated creek (Ipa Itako) part of the Lagos lagoon was investigated for twelve months (February 2010 - January 2011). The surface water pH varied between 6.5 (December 2010) and 8.6 (August 2010) indicating a slightly acidic to alkaline nature of the creek. The salinity was higher during the dry months (November- April) and phosphate - phosphorus and nitrate-nitrogen recorded highesst values (3.50 and 16.70 mg/L) respectively in June, 2010. Ninety three species belonging to forty nine genera from five classes (Bacillariophyceae, Chlorophyceae, Euglenophyceae, Cyanophyceae and Xanthophyceae) were recorded. Bacillariophyceae constituted the most abundant group making up 72.85% of cells/ml followed by the Chlorophytes (18.02%) then the blue green (7.65%), euglenoids (1.40%) and xanthophytes (0.07%) with only Vaucheria sp. recorded as a representative of the group. Higher phytoplankton diversity and cell counts were recorded in the dry months than in the wet months. Navicula, Pinnularia, Cymbella (Diatoms) and Closterium (Chlorophyceae) were more frequently occurring species. -

Ketu (Benin) Ketu Is a Historical Region in What Is Now the Republic of Benin, in the Area of the Town of Kétou

Ketu (Benin) Ketu is a historical region in what is now the Republic of Benin, in the area of the town of Kétou (Ketu). It is one of the oldest capitals of the Yoruba speaking people, tracing its establishment to a settlement founded by a daughter of Oduduwa, also known as Odudua, Oòdua and Eleduwa. The regents of the town were traditionally styled "Alaketu", and are believed to be related to the Egba sub-group of the Yoruba people in present-day Nigeria. Ketu is considered one of the seven original kingdoms established by the children of Oduduwa in Oyo mythic history, though this ancient pedigree has been somewhat neglected in contemporary Yoruba historical research, which tends to focus on communities within Nigeria. The exact status of Ketu within the Oyo empire however is contested. Oyo sources claim Ketu as a dependency with claims that the Ketu paid an annual tribute and that its ruler attended the Bere festival in Oyo. In any case, there is no doubt that Ketu and Oyo maintained friendly relations largely due to their historical, linguistic, cultural and ethnic ties.[1] The kingdom was one of the main enemies of the ascendant kingdom of Dahomey, often fighting against Dahomeans as part of Oyo's imperial forces, but ultimately succumbing to the Fon in the 1880s as the kingdom was ravaged. A large number of Ketu's citizens were sold into slavery during these raids, which accounts for the kingdom's importance in Brazilian Candomblé. Ketu is often known as Queto in Portuguese orthography. Ewe connection Ewe traditions refer to Ketu as Amedzofe ("origin of humanity") or Mawufe ("home of the Supreme Being"). -

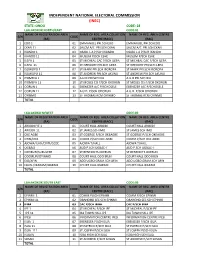

Ondo Code: 28 Lga:Akokok North/East Code:01 Name of Registration Area Name of Reg

INDEPENDENT NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION (INEC) STATE: ONDO CODE: 28 LGA:AKOKOK NORTH/EAST CODE:01 NAME OF REGISTRATION AREA NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 EDO 1 01 EMMANUEL PRI.SCHEDO EMMANUEL PRI.SCHEDO 2 EKAN 11 02 SALEM A/C PRI.SCH EKAN SALEM A/C PRI.SCH EKAN 3 IKANDO 1 03 OSABL L.A P/SCH IKANDO OSABL L.A P/SCH IKANDO 4 IKANDO 11 04 MUSLIM P/SCH ESHE MUSLIM P/SCH ESHE 5 ILEPA 1 05 ST MICHEAL CAC P/SCH ILEPA ST MICHEAL CAC P/SCH ILEPA 6 ILEPA 11 06 ST GREGORY PRI.SCH ILEPA ST GREGORY PRI.SCH ILEPA 7 ISOWOPO 1 07 ST MARK PRI.SCH IBOROPA ST MARK PRI.SCH IBOROPA 8 ISOWOPO 11 08 ST ANDREW PRI.SCH AKUNU ST ANDREW PRI.SCH AKUNU 9 IYOMEFA 1 09 A.U.D PRI.SCH IKU A.U.D PRI.SCH IKU 10 IYOMEFA 11 10 ST MOSES CIS P/SCH OKORUN ST MOSES CIS P/SCH OKORUN 11 OORUN 1 11 EBENEZER A/C P/SCHOSELE EBENEZER A/C P/SCHOSELE 12 OORUN 11 12 A.U.D. P/SCH ODORUN A.U.D. P/SCH ODORUN 13 OYINMO 13 ST THOMAS RCM OYINMO ST THOMAS RCM OYINMO TOTAL LGA:AKOKO N/WEST CODE:02 NAME OF REGISTRATION AREA NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 ARIGIDI IYE 1 01 COURT HALL ARIGIDI COURT HALL ARIGIDI 2 ARIGIDI 11 02 ST JAMES SCH IMO ST JAMES SCH IMO 3 OKE AGBE 03 ST GOERGE P/SCH OKEAGBE ST GOERGE P/SCH OKEAGBE 4 OYIN/OGE 04 COMM.P/SCH OKE AGBE COMM.P/SCH OKE AGBE 5 AJOWA/ILASI/ERITI/GEDE 05 AJOWA T/HALL AJOWA T/HALL 6 OGBAGI 06 AUD P.SCH OGBAC-I AUD P.SCH OGBAC-I 7 OKEIRUN/SURULERE 07 ST BENEDICTS OKERUN ST BENEDICTS OKERUN 8 ODOIRUN/OYINMO 08 COURT HALL ODO IRUN COURT HALL ODO IRUN 9 ESE/AFIN 09 ADO UGBO GRAM.SCH AFIN ADO UGBO GRAM.SCH AFIN 10 EBUSU/IKARAM/IBARAM 10 COURT HALL IKARAM COURT HALL IKARAM TOTAL LGA:AKOKOK SOUTH EAST CODE:03 NAME OF REGISTRATION AREA NAME OF REG. -

Yoruba Art & Culture

Yoruba Art & Culture Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology University of California, Berkeley Yoruba Art and Culture PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Written and Designed by Nicole Mullen Editors Liberty Marie Winn Ira Jacknis Special thanks to Tokunbo Adeniji Aare, Oduduwa Heritage Organization. COPYRIGHT © 2004 PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY AND THE REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY ◆ UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT BERKELEY BERKELEY, CA 94720-3712 ◆ 510-642-3682 ◆ HTTP://HEARSTMUSEUM.BERKELEY.EDU Table of Contents Vocabulary....................4 Western Spellings and Pronunciation of Yoruba Words....................5 Africa....................6 Nigeria....................7 Political Structure and Economy....................8 The Yoruba....................9, 10 Yoruba Kingdoms....................11 The Story of How the Yoruba Kingdoms Were Created....................12 The Colonization and Independence of Nigeria....................13 Food, Agriculture and Trade....................14 Sculpture....................15 Pottery....................16 Leather and Beadwork....................17 Blacksmiths and Calabash Carvers....................18 Woodcarving....................19 Textiles....................20 Religious Beliefs....................21, 23 Creation Myth....................22 Ifa Divination....................24, 25 Music and Dance....................26 Gelede Festivals and Egugun Ceremonies....................27 Yoruba Diaspora....................28 -

Prof. Dr. Kayode AJAYI Dr. Muyiwa ADEYEMI Faculty of Education Olabisi Onabanjo University, Ago-Iwoye, NIGERIA

International Journal on New Trends in Education and Their Implications April, May, June 2011 Volume: 2 Issue: 2 Article: 4 ISSN 1309-6249 UNIVERSAL BASIC EDUCATION (UBE) POLICY IMPLEMENTATION IN FACILITIES PROVISION: Ogun State as a Case Study Prof. Dr. Kayode AJAYI Dr. Muyiwa ADEYEMI Faculty of Education Olabisi Onabanjo University, Ago-Iwoye, NIGERIA ABSTRACT The Universal Basic Education Programme (UBE) which encompasses primary and junior secondary education for all children (covering the first nine years of schooling), nomadic education and literacy and non-formal education in Nigeria have adopted the “collaborative/partnership approach”. In Ogun State, the UBE Act was passed into law in 2005 after that of the Federal government in 2004, hence, the demonstration of the intention to make the UBE free, compulsory and universal. The aspects of the policy which is capital intensive require the government to provide adequately for basic education in the area of organization, funding, staff development, facilities, among others. With the commencement of the scheme in 1999/2000 until-date, Ogun State, especially in the area of facility provision, has joined in the collaborative effort with the Federal government through counter-part funding to provide some facilities to schools in the State, especially at the Primary level. These facilities include textbooks (in core subjects’ areas- Mathematics, English, Social Studies and Primary Science), blocks of classrooms, furniture, laboratories/library, teachers, etc. This study attempts to assess the level of articulation by the Ogun State Government of its UBE policy within the general framework of the scheme in providing facilities to schools at the primary level. -

Reglas De Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe) a Book by Lydia Cabrera an English Translation from the Spanish

THE KONGO RULE: THE PALO MONTE MAYOMBE WISDOM SOCIETY (REGLAS DE CONGO: PALO MONTE MAYOMBE) A BOOK BY LYDIA CABRERA AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION FROM THE SPANISH Donato Fhunsu A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature (Comparative Literature). Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Inger S. B. Brodey Todd Ramón Ochoa Marsha S. Collins Tanya L. Shields Madeline G. Levine © 2016 Donato Fhunsu ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Donato Fhunsu: The Kongo Rule: The Palo Monte Mayombe Wisdom Society (Reglas de Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe) A Book by Lydia Cabrera An English Translation from the Spanish (Under the direction of Inger S. B. Brodey and Todd Ramón Ochoa) This dissertation is a critical analysis and annotated translation, from Spanish into English, of the book Reglas de Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe, by the Cuban anthropologist, artist, and writer Lydia Cabrera (1899-1991). Cabrera’s text is a hybrid ethnographic book of religion, slave narratives (oral history), and folklore (songs, poetry) that she devoted to a group of Afro-Cubans known as “los Congos de Cuba,” descendants of the Africans who were brought to the Caribbean island of Cuba during the trans-Atlantic Ocean African slave trade from the former Kongo Kingdom, which occupied the present-day southwestern part of Congo-Kinshasa, Congo-Brazzaville, Cabinda, and northern Angola. The Kongo Kingdom had formal contact with Christianity through the Kingdom of Portugal as early as the 1490s. -

Analysis of Beef Consumption Pattern Among Rural Households in Yewa South Local Government Area of Ogun State, Nigeria

Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa (Volume 17, No.8, 2015) ISSN: 1520-5509 Clarion University of Pennsylvania, Clarion, Pennsylvania ANALYSIS OF BEEF CONSUMPTION PATTERN AMONG RURAL HOUSEHOLDS IN YEWA SOUTH LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA OF OGUN STATE, NIGERIA Akerele, Ezekiel Olaoluwa; Ologbon, Olugbenga Adesoji Christopher; Otunaiya, Abiodun Olanrewaju; and Ambali, Isiaka Omotuyole Department of Agricultural Economics and Farm Management, College of Agricultural Sciences Olabisi Onabanjo University, Yewa Campus, Ayetoro, Ogun State ABSTRACT This study analysed the consumption pattern of beef among rural households in Yewa South Local Government Area of Ogun State, Nigeria. A two-stage simple random sampling technique was employed, and with the help of 120 well- structured questionnaires, data were collected from 120 rural households. The collected data were then subjected to both descriptive and econometrics statistics (regression analysis, Marginal Propensity To Consume (MPC), price elasticity of beef). The results indicated that the highest age of the consumers was within the age bracket of 30-39 years. 65% of the population was married. Secondary education takes the dominance with 49.2% having it. Their major occupation was petty trading (45%). The results showed that beef price and monthly expenditure on food items negatively affected beef consumption in the area, while beef preference, fish price, beef availability, total monthly income and major occupation positively affected beef consumption. Price elasticity of beef was found out to be -0.90006. The Marginal Propensity Consume of beef was 0.0017484. The identified major constraint to beef consumption in the area was low availability of beef. It is therefore recommended that large scale beef cattle rearing should be encouraged which will help to increase the production of safe beef for consumption. -

Land Accessibility Characteristics Among Migrants in Yewa North Local Government Area of Ogun State, Nigeria

Asian Research Journal of Arts & Social Sciences 2(1): 1-12, 2017; Article no.ARJASS.30086 SCIENCEDOMAIN international www.sciencedomain.org Land Accessibility Characteristics among Migrants in Yewa North Local Government Area of Ogun State, Nigeria Gbenga John Oladehinde 1* , Kehinde Popoola 1, Afolabi Fatusin 2 and Gideon Adeyeni 1 1Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Osun State Nigeria. 2Department of Geography and Planning Sciences, Adekunle Ajasin University, Akungba-Akoko, Ondo State, Nigeria. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out collaboratively by all authors. Author GJO designed the study and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Authors KP and AF supervised the preparation of the first draft of the manuscript and managed the literature searches while author GA led and managed the data analyses. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/ARJASS/2017/30086 Editor(s): (1) Raffaela Giovagnoli, Pontifical Lateran University, Piazza San Giovanni in Laterano 4, Rome, Italy. (2) Sheying Chen, Social Policy and Administration, Pace University, New York, USA. Reviewers: (1) F. Famuyiwa, University of Lagos, Nigeria. (2) Lusugga Kironde, Ardhi University, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sciencedomain.org/review-history/17570 Received 16 th October 2016 Accepted 14 th January 2017 Original Research Article st Published 21 January 2017 ABSTRACT Aim: The study investigated challenges of land accessibility among migrants in Yewa North Local Government Area of Ogun State, Nigeria. Methodology: Data were obtained through questionnaire administration on a Migrant household head. Multistage sampling technique was used for selection of 161 respondents for the study. -

KETU MYTHS and the STATUS of WOMEN: a Structural Interpretation

NEXUS 8:1 (1990) 47 KETU MYTHS AND THE STATUS OF WOMEN: A Structural Interpretation Emmanuel Babatunde University of Lagos, Nigeria ABSTRACT Modern literature on the status of Yoruba women of South Western Nigeria has corrected the view that Yoruba women were suppressed, by throwing into relief areas of their prominence. B. Awe has drawn attention to the prominent part women like Iyalode played in traditional Yoruba politics (1977, 1979). J.A. Atanda (1979) and S.O. Babayemi (1979) have stressed the significant roles of women in the palace organization of Oyo. N. Sudarka (1973) and Karanja (1980) have explored the interesting area of Yoruba market women, showing that the economic strength which such economic enterprises confer made Yoruba women not only prominent but independent. Karanja, on the other hand, accepted that although economic enterprise brought a considerable measure of strength and prominence to the Yoruba woman, her relationship with her husband may not be interpreted as one marked with complete independence. In drawing attention to the role of women as mothers and as occupiers of the innermost and sacrosanct space within Yoruba domains, H. Callaway has demonstrated the importance of Yoruba women to central features of Yoruba society (1978). In this present work I discuss some Yoruba myths in order to throw into relief the prominence of women. RESUME La literature recente concernant I'etat des femmes Yoruba au sud ouest du Niger a corrige I'impression que les femmes Yoruba sont suppressees, en iIIuminant leur proeminence dans plusieurs aspects sociaux. B. Awe a demontre I'importance des femmes telle que Iyalode dans Ie domaine politique traditionnel (1977, 1979). -

PROVISIONAL LIST.Pdf

S/N NAME YEAR OF CALL BRANCH PHONE NO EMAIL 1 JONATHAN FELIX ABA 2 SYLVESTER C. IFEAKOR ABA 3 NSIKAK UTANG IJIOMA ABA 4 ORAKWE OBIANUJU IFEYINWA ABA 5 OGUNJI CHIDOZIE KINGSLEY ABA 6 UCHENNA V. OBODOCHUKWU ABA 7 KEVIN CHUKWUDI NWUFO, SAN ABA 8 NWOGU IFIONU TAGBO ABA 9 ANIAWONWA NJIDEKA LINDA ABA 10 UKOH NDUDIM ISAAC ABA 11 EKENE RICHIE IREMEKA ABA 12 HIPPOLITUS U. UDENSI ABA 13 ABIGAIL C. AGBAI ABA 14 UKPAI OKORIE UKAIRO ABA 15 ONYINYECHI GIFT OGBODO ABA 16 EZINMA UKPAI UKAIRO ABA 17 GRACE UZOME UKEJE ABA 18 AJUGA JOHN ONWUKWE ABA 19 ONUCHUKWU CHARLES NSOBUNDU ABA 20 IREM ENYINNAYA OKERE ABA 21 ONYEKACHI OKWUOSA MUKOSOLU ABA 22 CHINYERE C. UMEOJIAKA ABA 23 OBIORA AKINWUMI OBIANWU, SAN ABA 24 NWAUGO VICTOR CHIMA ABA 25 NWABUIKWU K. MGBEMENA ABA 26 KANU FRANCIS ONYEBUCHI ABA 27 MARK ISRAEL CHIJIOKE ABA 28 EMEKA E. AGWULONU ABA 29 TREASURE E. N. UDO ABA 30 JULIET N. UDECHUKWU ABA 31 AWA CHUKWU IKECHUKWU ABA 32 CHIMUANYA V. OKWANDU ABA 33 CHIBUEZE OWUALAH ABA 34 AMANZE LINUS ALOMA ABA 35 CHINONSO ONONUJU ABA 36 MABEL OGONNAYA EZE ABA 37 BOB CHIEDOZIE OGU ABA 38 DANDY CHIMAOBI NWOKONNA ABA 39 JOHN IFEANYICHUKWU KALU ABA 40 UGOCHUKWU UKIWE ABA 41 FELIX EGBULE AGBARIRI, SAN ABA 42 OMENIHU CHINWEUBA ABA 43 IGNATIUS O. NWOKO ABA 44 ICHIE MATTHEW EKEOMA ABA 45 ICHIE CORDELIA CHINWENDU ABA 46 NNAMDI G. NWABEKE ABA 47 NNAOCHIE ADAOBI ANANSO ABA 48 OGOJIAKU RUFUS UMUNNA ABA 49 EPHRAIM CHINEDU DURU ABA 50 UGONWANYI S. AHAIWE ABA 51 EMMANUEL E. -

African Concepts of Energy and Their Manifestations Through Art

AFRICAN CONCEPTS OF ENERGY AND THEIR MANIFESTATIONS THROUGH ART A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Renée B. Waite August, 2016 Thesis written by Renée B. Waite B.A., Ohio University, 2012 M.A., Kent State University, 2016 Approved by ____________________________________________________ Fred Smith, Ph.D., Advisor ____________________________________________________ Michael Loderstedt, M.F.A., Interim Director, School of Art ____________________________________________________ John R. Crawford-Spinelli, D.Ed., Dean, College of the Arts TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES………………………………………….. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS …………………………………… vi CHAPTERS I. Introduction ………………………………………………… 1 II. Terms and Art ……………………………………………... 4 III. Myths of Origin …………………………………………. 11 IV. Social Structure …………………………………………. 20 V. Divination Arts …………………………………………... 30 VI. Women as Vessels of Energy …………………………… 42 VII. Conclusion ……………………………………….…...... 56 VIII. Images ………………………………………………… 60 IX. Bibliography …………………………………………….. 84 X. Further Reading ………………………………………….. 86 iii LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1: Porogun Quarter, Ijebu-Ode, Nigeria, 1992, Photograph by John Pemberton III http://africa.si.edu/exhibits/cosmos/models.html. ……………………………………… 60 Figure 2: Yoruba Ifa Divination Tapper (Iroke Ifa) Nigeria; Ivory. 12in, Baltimore Museum of Art http://www.artbma.org/. ……………………………………………… 61 Figure 3.; Yoruba Opon Ifa (Divination Tray), Nigerian; carved wood 3/4 x 12 7/8 x 16 in. Smith College Museum of Art, http://www.smith.edu/artmuseum/. ………………….. 62 Figure 4. Ifa Divination Vessel; Female Caryatid (Agere Ifa); Ivory, wood or coconut shell inlay. Nigeria, Guinea Coast The Metropolitan Museum of Art, http://www.metmuseum.org. ……………………… 63 Figure 5. Beaded Crown of a Yoruba King. Nigerian; L.15 (crown), L.15 (fringe) in.