Africana Studies Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction: Introducing Yemoja

1 2 3 4 5 Introduction 6 7 8 Introducing Yemoja 9 10 11 12 Solimar Otero and Toyin Falola 13 14 15 16 17 18 Mother I need 19 mother I need 20 mother I need your blackness now 21 as the august earth needs rain. 22 —Audre Lorde, “From the House of Yemanjá”1 23 24 “Yemayá es Reina Universal porque es el Agua, la salada y la dul- 25 ce, la Mar, la Madre de todo lo creado / Yemayá is the Universal 26 Queen because she is Water, salty and sweet, the Sea, the Mother 27 of all creation.” 28 —Oba Olo Ocha as quoted in Lydia Cabrera’s Yemayá y Ochún.2 29 30 31 In the above quotes, poet Audre Lorde and folklorist Lydia Cabrera 32 write about Yemoja as an eternal mother whose womb, like water, makes 33 life possible. They also relate in their works the shifting and fluid nature 34 of Yemoja and the divinity in her manifestations and in the lives of her 35 devotees. This book, Yemoja: Gender, Sexuality, and Creativity in the 36 Latina/o and Afro-Atlantic Diasporas, takes these words of supplica- 37 tion and praise as an entry point into an in-depth conversation about 38 the international Yoruba water deity Yemoja. Our work brings together 39 the voices of scholars, practitioners, and artists involved with the inter- 40 sectional religious and cultural practices involving Yemoja from Africa, 41 the Caribbean, North America, and South America. Our exploration 42 of Yemoja is unique because we consciously bridge theory, art, and 43 xvii SP_OTE_INT_xvii-xxxii.indd 17 7/9/13 5:13 PM xviii Solimar Otero and Toyin Falola 1 practice to discuss orisa worship3 within communities of color living in 2 postcolonial contexts. -

The Exodus and Identity Formation in View of the Yoruba Origin and Migration Narratives1

http://scriptura.journals.ac.za Scriptura 108 (2011), pp. 342-356 THE EXODUS AND IDENTITY FORMATION IN VIEW OF THE YORUBA ORIGIN AND MIGRATION NARRATIVES1 Funlola Olojede Old and New Testament Stellenbosch University The past is but the beginning of a beginning (HG Wells) Abstract Certain elements of the origin and migration narratives of the Yoruba such as a common ancestor, common ancestral home, common belief in the Supreme Deity provide a basis for identity formation and recognition among the people. It is argued that the narratives help to bring to light the memories of the Exodus and Israel’s recollection of Yahweh as the root of its identity. The juxtaposition of cosmogonic myths and migration theories foregrounds the elements of identity formation of the Yoruba people and have a parallel in the blending of both cosmic and migration elements in Exodus 14-15:18. This blending also points out clearly the role of Yahweh as the main character in the Sea event. Key Words: Exodus, Identity, Migration, Yahweh, Yorùbá Introduction The hypothesis is that Yorùbá traditions of origin and migration influence the process of identity formation in certain ways and that this implication for identity may contain certain heuristic values that can be used to interpret the exodus in a contextual way. In what follows, a literature review of basic cosmogonic myths and migration theories of the Yorùbá is carried out to determine their impact on the people’s identity formation. This is followed by a brief literary consideration of the Sea event (Exod 14-15) which is a two-way prosaic and poetic rendition of the sea crossing by the children of Israel after their departure from Egypt. -

Ìyá Agbára Ìyá Agbára

Ìyá Agbára Ìyá Agbára Virginia Borges, 11TH BERLIN Gil DuOdé e BIENNALE 2020 Virginia de Medeiros THE CRACK BEGINS WITHIN 1 Claudia Sampaio Silva 6 2 Diana Schreyer 14 3 Virginia Borges 24 4 Virginia de Medeiros 35 5 Lucrécia Boebes-Ruin 45 6 Vera Regina Menezes 60 7 Nina Graeff 68 8 Nitzan Meilin 75 9 Mirah Laline 85 10 Luanny Tiago 95 11 Gilmara Guimarães 114 “Candomblé is a feminine religion, created by women. The strength of Candomblé is feminine. Why by women? Because it is the woman who generates. It is only the woman who gives birth. It’s only the woman who has a uterus. Candomblé religiosity is comprehensive, it embraces everyone. Who embraces a big family? It is always the mother”. Babalorixá Muralesimbe (Murah Soares) Spiritual leader of Ilê Obá Sileké 1 Claudia Sampaio Silva My name is Claudia Sampaio Silva, I was born in Bahia, in the Chapada region, close to Andaraí in a very small town called Colônia de Itaitê. i went to Salvador at the age of five with my family. i arrived in Germany for the first time in 1988. i came to visit an aunt who had two small children. She was overwhelmed with them. i came to help her and took the opportunity to leave Brazil. it was in the 1980s at the end of the Military Coup of 1964 and the beginning of the so-called democracy. it was a very conflicted time! i took a leave of absence from college and stayed in Berlin for a year, from 1988 to 1989. -

Yoruba Art & Culture

Yoruba Art & Culture Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology University of California, Berkeley Yoruba Art and Culture PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Written and Designed by Nicole Mullen Editors Liberty Marie Winn Ira Jacknis Special thanks to Tokunbo Adeniji Aare, Oduduwa Heritage Organization. COPYRIGHT © 2004 PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY AND THE REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY ◆ UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT BERKELEY BERKELEY, CA 94720-3712 ◆ 510-642-3682 ◆ HTTP://HEARSTMUSEUM.BERKELEY.EDU Table of Contents Vocabulary....................4 Western Spellings and Pronunciation of Yoruba Words....................5 Africa....................6 Nigeria....................7 Political Structure and Economy....................8 The Yoruba....................9, 10 Yoruba Kingdoms....................11 The Story of How the Yoruba Kingdoms Were Created....................12 The Colonization and Independence of Nigeria....................13 Food, Agriculture and Trade....................14 Sculpture....................15 Pottery....................16 Leather and Beadwork....................17 Blacksmiths and Calabash Carvers....................18 Woodcarving....................19 Textiles....................20 Religious Beliefs....................21, 23 Creation Myth....................22 Ifa Divination....................24, 25 Music and Dance....................26 Gelede Festivals and Egugun Ceremonies....................27 Yoruba Diaspora....................28 -

Biography of a Runaway Slave</Cite>

Miguel Barnet. Biography of a Runaway Slave. Willimantic, Conn.: Curbstone Press, 1994. 217 pp. $11.95, paper, ISBN 978-1-880684-18-4. Reviewed by Dale T. Graden Published on H-Ethnic (October, 1996) Few documentary sources exist from the Car‐ preter as "the frst personal and detailed account ibbean islands and the Latin American mainland of a Maroon [escaped] slave in Cuban and Spanish written by Africans or their descendants that de‐ American literature and a valuable document to scribe their life under enslavement. In Brazil, two historians and students of slavery" (Luis, p. 200). mulatto abolitionists wrote sketchy descriptions This essay will explore how testimonial literature of their personal experiences, and one autobiog‐ can help us better to understand past events. It raphy of a black man was published before eman‐ will also examine problems inherent in interpret‐ cipation. In contrast, several thousand slave nar‐ ing personal testimony based on memories of ratives and eight full-length autobiographies were events that occurred several decades in the past. published in the United States before the outbreak Esteban Mesa Montejo discussed his past with of the Civil War (1860-1865) (Conrad, p. xix). In the Cuban ethnologist Miguel Barnet in taped in‐ Cuba, one slave narrative appeared in the nine‐ terviews carried out in 1963. At the age of 103, teenth century. Penned by Juan Francisco Man‐ most likely Esteban Montejo understood that he zano, the Autobiografia (written in 1835, pub‐ was the sole living runaway slave on the island lished in England in 1840, and in Cuba in 1937) re‐ and that his words and memories might be con‐ counted the life of an enslaved black who learned sidered important enough to be published. -

Reglas De Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe) a Book by Lydia Cabrera an English Translation from the Spanish

THE KONGO RULE: THE PALO MONTE MAYOMBE WISDOM SOCIETY (REGLAS DE CONGO: PALO MONTE MAYOMBE) A BOOK BY LYDIA CABRERA AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION FROM THE SPANISH Donato Fhunsu A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature (Comparative Literature). Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Inger S. B. Brodey Todd Ramón Ochoa Marsha S. Collins Tanya L. Shields Madeline G. Levine © 2016 Donato Fhunsu ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Donato Fhunsu: The Kongo Rule: The Palo Monte Mayombe Wisdom Society (Reglas de Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe) A Book by Lydia Cabrera An English Translation from the Spanish (Under the direction of Inger S. B. Brodey and Todd Ramón Ochoa) This dissertation is a critical analysis and annotated translation, from Spanish into English, of the book Reglas de Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe, by the Cuban anthropologist, artist, and writer Lydia Cabrera (1899-1991). Cabrera’s text is a hybrid ethnographic book of religion, slave narratives (oral history), and folklore (songs, poetry) that she devoted to a group of Afro-Cubans known as “los Congos de Cuba,” descendants of the Africans who were brought to the Caribbean island of Cuba during the trans-Atlantic Ocean African slave trade from the former Kongo Kingdom, which occupied the present-day southwestern part of Congo-Kinshasa, Congo-Brazzaville, Cabinda, and northern Angola. The Kongo Kingdom had formal contact with Christianity through the Kingdom of Portugal as early as the 1490s. -

Objects of Desire

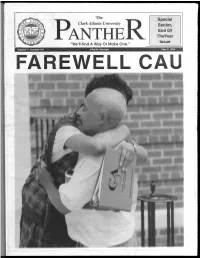

Special Senior, End Of TheYear Issue Volume I • Number XVI Atlanta, Georgia May 2, 1994 FAREWELL CAU P2 May 2, 1994 The Panther AmeriCorps is the new domestic AmeriCorps... Peace Corps where thousands of young people will soon be getting the new National Service things done through service in exchange for help in financing movement that will their higher education or repaying their student loans. get things done. Starting this fall, thousands Watch for of AmeriCorps members will fan out across the nation to meet AmeriCorps, coming the needs of communities everywhere. And the kinds of soon to your community... things they will help get done can truly change America- and find out more things like immunizing our infants...tutoring our teenagers... by calling: k keeping our schools safe... restoring our natural resources 1-800-94-ACORPS. ...and securing more independent ^^Nives for our and our elderly. TDD 1-800-833-3722 Come hear L L Cool J at an AmeriCorps Campus Tour Rally for Change with A.U.C. Council of Presidents and other special guests. May 5,12 noon Morehouse Campus Green The Panther May 2, 1994 P3 Seniors Prepare The End Of The Road For Life After College By Johane Thomas AUC, and their experiences in the Contributing Writer classroom and their own personal experiences will carry over into the the work place. That special time of the year is here Eric Brown of Morehouse College again. As students prepare for gradua tion, they express concern over find plans to attend UCLA in the fall. As a ing jobs, respect in the workplace and Pre-Med major, Eric feels that his their experiences while attending learned skills will help him to suceed school here in the AUC. -

Black Rhetoric: the Art of Thinking Being

BLACK RHETORIC: THE ART OF THINKING BEING by APRIL LEIGH KINKEAD Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON May 2013 Copyright © by April Leigh Kinkead 2013 All Rights Reserved ii Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without the guidance, advice, and support of others. I would like to thank my advisor, Cedrick May, for his taking on the task of directing my dissertation. His knowledge, advice, and encouragement helped to keep me on track and made my completing this project possible. I am grateful to Penelope Ingram for her willingness to join this project late in its development. Her insights and advice were as encouraging as they were beneficial to my project’s aims. I am indebted to Kevin Gustafson, whose careful reading and revisions gave my writing skills the boost they needed. I am a better writer today thanks to his teachings. I also wish to extend my gratitude to my school colleagues who encouraged me along the way and made this journey an enjoyable experience. I also wish to thank the late Emory Estes, who inspired me to pursue graduate studies. I am equally grateful to Luanne Frank for introducing me to Martin Heidegger’s theories early in my graduate career. This dissertation would not have come into being without that introduction or her guiding my journey through Heidegger’s theories. I must also thank my family and friends who have stood by my side throughout this long journey. -

Atlantic Slavery and the Making of the Modern World Wenner-Gren Symposium Supplement 22

T HE WENNER-GREN SYMPOSIUM SERIES CURRENT ANTHROPOLOGY A TLANTIC SLAVERY AND THE MAKING OF THE MODERN WORLD I BRAHIMA THIAW AND DEBORAH L. MACK, GUEST EDITORS A tlantic Slavery and the Making of the Modern World: Wenner-Gren Symposium Supplement 22 Atlantic Slavery and the Making of the Modern World: Experiences, Representations, and Legacies An Introduction to Supplement 22 Atlantic Slavery and the Rise of the Capitalist Global Economy V The Slavery Business and the Making of “Race” in Britain OLUME 61 and the Caribbean Archaeology under the Blinding Light of Race OCTOBER 2020 VOLUME SUPPLEMENT 61 22 From Country Marks to DNA Markers: The Genomic Turn S UPPLEMENT 22 in the Reconstruction of African Identities Diasporic Citizenship under Debate: Law, Body, and Soul Slavery, Anthropological Knowledge, and the Racialization of Africans Sovereignty after Slavery: Universal Liberty and the Practice of Authority in Postrevolutionary Haiti O CTOBER 2020 From the Transatlantic Slave Trade to Contemporary Ethnoracial Law in Multicultural Ecuador: The “Changing Same” of Anti-Black Racism as Revealed by Two Lawsuits Filed by Afrodescendants Serving Status on the Gambia River Before and After Abolition The Problem: Religion within the World of Slaves The Crying Child: On Colonial Archives, Digitization, and Ethics of Care in the Cultural Commons A “tone of voice peculiar to New-England”: Fugitive Slave Advertisements and the Heterogeneity of Enslaved People of African Descent in Eighteenth-Century Quebec Valongo: An Uncomfortable Legacy Raising -

ADJUSTMENT STYLES and EXPRESSION of POST-TRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDERS AMONG SELECTED POLICE in OSOGBO METROPOLIS Ajibade B.L1

International Journal of Health and Psychology Research Vol.6, No.2, pp.21-35, September 2018 ___Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) ADJUSTMENT STYLES AND EXPRESSION OF POST-TRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDERS AMONG SELECTED POLICE IN OSOGBO METROPOLIS Ajibade B.L1, Ayeni Adebusola Raphael2, Akao Olugbenga D1 and Omotoriogun M.I2 1Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, College of Health Sciences, Faculty of Clinical Sciences, Department of Nursing Science, Osogbo 2Achievers University, Department of Nursing Science, Owo ABSTRACT: This study explores the exposure to post-traumatic stress disorder among the police and expression of PTSD with the resultant adjustment strategies utilization to cope with PTSD. Descriptive survey research design was employed to select 200 respondents using simple random technique and Taro Yamane to determine the sample size. Self structured three sections questionnaire was used in data collection which lasted for the period of four months and descriptive statistics was used to analyse the collected data. The result revealed that the respondents mean age was 35.65±5.97 and majority of the respondents were men. The respondents expressed exposure to PSTD at various degree where “a little bit” on likert scale with mean value of 56.82±7.54. All the respondents adopted various adjustments strategies to combat PTSD which resulted in effective coping mechanism. In conclusion, the respondents’ ability to cope with post-traumatic stress disorders was in tandem with active middle age and readiness to defend the sovereignty of their nation. KEYWORDS: Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, Expression Adjustment Styles INTRODUCTION Policing necessitates exposure to traumatic, violent and horrific events, which can lead to an increased risk for developing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). -

Cth 821 Course Title: African Traditional Religious Mythology and Cosmology

NATIONAL OPEN UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COURSE CODE: CTH 821 COURSE TITLE: AFRICAN TRADITIONAL RELIGIOUS MYTHOLOGY AND COSMOLOGY 1 Course Code: CTH 821 Course Title: African Traditional Religious Mythology and Cosmology Course Developer: Rev. Fr. Dr. Michael .N. Ushe Department of Christian Theology School of Arts and Social Sciences National Open University of Nigeria, Lagos Course Writer: Rev. Fr. Dr. Michael .N. Ushe Department of Christian Theology School of Arts and Social Sciences National Open University of Nigeria, Lagos Programme Leader: Rev. Fr. Dr. Michael .N. Ushe Department of Christian Theology School of Arts and Social Sciences National Open University of Nigeria, Lagos Course Title: CTH 821 AFRICAN TRADITIONAL RELIGIOUS MYTHOLOGY AND COSMOLOGY COURSE DEVELOPER/WRITER: Rev. Fr. Dr. Ushe .N. Michael 2 National Open University of Nigeria, Lagos COURSE MODERATOR: Rev. Fr. Dr. Mike Okoronkwo National Open University of Nigeria, Lagos PROGRAMME LEADER: Rev. Fr. Dr. Ushe .N. Michael National Open University of Nigeria, Lagos CONTENTS PAGE Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………… …...i What you will learn in this course…………………………………………………………….…i-ii 3 Course Aims………………………………………………………..……………………………..ii Course objectives……………………………………………………………………………...iii-iii Working Through this course…………………………………………………………………….iii Course materials…………………………………………………………………………..……iv-v Study Units………………………………………………………………………………………..v Set Textbooks…………………………………………………………………………………….vi Assignment File…………………………………………………………………………………..vi -

Trends in Owo Traditional Sculptures: 1995 – 2010

Mgbakoigba, Journal of African Studies. Vol.5 No.1. December 2015 TRENDS IN OWO TRADITIONAL SCULPTURES: 1995 – 2010 Ebenezer Ayodeji Aseniserare Department of Fine and Applied Arts University of Benin, Benin City [email protected] 08034734927, 08057784545 and Efemena I. Ononeme Department of Fine and Applied Arts University of Benin, Benin City [email protected] [email protected] 08023112353 Abstract This study probes into the origin, style and patronage of the traditional sculptures in Owo kingdom between 1950 and 2010. It examines comparatively the sculpture of the people and its affinity with Benin and Ife before and during the period in question with a view to predicting the future of the sculptural arts of the people in the next few decades. Investigations of the study rely mainly on both oral and written history, observation, interviews and photographic recordings of visuals, visitations to traditional houses and Owo museum, oral interview of some artists and traditionalists among others. Oral data were also employed through unstructured interviews which bothered on analysis, morphology, formalism, elements and features of the forms, techniques and styles of Owo traditional sculptures, their resemblances and relationship with Benin and Ife artefacts which were traced back to the reigns of both Olowo Ojugbelu 1019 AD to Olowo Oshogboye, the Olowo of Owo between 1600 – 1684 AD, who as a prince, lived and was brought up by the Oba of Benin. He cleverly adopted some of Benin‟s sculptural and historical culture and artefacts including carvings, bronze work, metal work, regalia, bead work, drums and some craftsmen with him on his return to Owo to reign.