ADJUSTMENT STYLES and EXPRESSION of POST-TRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDERS AMONG SELECTED POLICE in OSOGBO METROPOLIS Ajibade B.L1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trends in Owo Traditional Sculptures: 1995 – 2010

Mgbakoigba, Journal of African Studies. Vol.5 No.1. December 2015 TRENDS IN OWO TRADITIONAL SCULPTURES: 1995 – 2010 Ebenezer Ayodeji Aseniserare Department of Fine and Applied Arts University of Benin, Benin City [email protected] 08034734927, 08057784545 and Efemena I. Ononeme Department of Fine and Applied Arts University of Benin, Benin City [email protected] [email protected] 08023112353 Abstract This study probes into the origin, style and patronage of the traditional sculptures in Owo kingdom between 1950 and 2010. It examines comparatively the sculpture of the people and its affinity with Benin and Ife before and during the period in question with a view to predicting the future of the sculptural arts of the people in the next few decades. Investigations of the study rely mainly on both oral and written history, observation, interviews and photographic recordings of visuals, visitations to traditional houses and Owo museum, oral interview of some artists and traditionalists among others. Oral data were also employed through unstructured interviews which bothered on analysis, morphology, formalism, elements and features of the forms, techniques and styles of Owo traditional sculptures, their resemblances and relationship with Benin and Ife artefacts which were traced back to the reigns of both Olowo Ojugbelu 1019 AD to Olowo Oshogboye, the Olowo of Owo between 1600 – 1684 AD, who as a prince, lived and was brought up by the Oba of Benin. He cleverly adopted some of Benin‟s sculptural and historical culture and artefacts including carvings, bronze work, metal work, regalia, bead work, drums and some craftsmen with him on his return to Owo to reign. -

Odo/Ota Local Government Secretariat, Sango - Agric

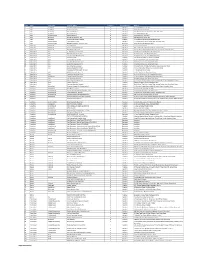

S/NO PLACEMENT DEPARTMENT ADO - ODO/OTA LOCAL GOVERNMENT SECRETARIAT, SANGO - AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 1 OTA, OGUN STATE AGEGE LOCAL GOVERNMENT, BALOGUN STREET, MATERNITY, AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 2 SANGO, AGEGE, LAGOS STATE AHMAD AL-IMAM NIG. LTD., NO 27, ZULU GAMBARI RD., ILORIN AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 3 4 AKTEM TECHNOLOGY, ILORIN, KWARA STATE AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 5 ALLAMIT NIG. LTD., IBADAN, OYO STATE AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 6 AMOULA VENTURES LTD., IKEJA, LAGOS STATE AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING CALVERTON HELICOPTERS, 2, PRINCE KAYODE, AKINGBADE MECHANICAL ENGINEERING 7 CLOSE, VICTORIA ISLAND, LAGOS STATE CHI-FARM LTD., KM 20, IBADAN/LAGOS EXPRESSWAY, AJANLA, AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 8 IBADAN, OYO STATE CHINA CIVIL ENGINEERING CONSTRUCTION CORPORATION (CCECC), KM 3, ABEOKUTA/LAGOS EXPRESSWAY, OLOMO - ORE, AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 9 OGUN STATE COCOA RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF NIGERIA (CRIN), KM 14, IJEBU AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 10 ODE ROAD, IDI - AYANRE, IBADAN, OYO STATE COKER AGUDA LOCAL COUNCIL, 19/29, THOMAS ANIMASAUN AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 11 STREET, AGUDA, SURULERE, LAGOS STATE CYBERSPACE NETWORK LTD.,33 SAKA TIINUBU STREET. AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 12 VICTORIA ISLAND, LAGOS STATE DE KOOLAR NIGERIA LTD.,PLOT 14, HAKEEM BALOGUN STREET, AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING OPP. TECHNICAL COLLEGE, AGIDINGBI, IKEJA, LAGOS STATE 13 DEPARTMENT OF PETROLEUM RESOURCES, 11, NUPE ROAD, OFF AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 14 AHMAN PATEGI ROAD, G.R.A, ILORIN, KWARA STATE DOLIGERIA BIOSYSTEMS NIGERIA LTD, 1, AFFAN COMPLEX, 1, AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 15 OLD JEBBA ROAD, ILORIN, KWARA STATE Page 1 SIWES PLACEMENT COMPANIES & ADDRESSES.xlsx S/NO PLACEMENT DEPARTMENT ESFOOS STEEL CONSTRUCTION COMPANY, OPP. SDP, OLD IFE AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 16 ROAD, AKINFENWA, EGBEDA, IBADAN, OYO STATE 17 FABIS FARMS NIGERIA LTD., ILORIN, KWARA STATE AGRIC. -

Surveillance of Anti-HCV Antibody Amongst In-School Youth in A

ORIGINAL ARTICLE AFRICAN JOURNAL OF CLINICAL AND EXPERIMENTAL MICROBIOLOGY ISBN 1595-689X JANUARY 2019 VOL20 No.1 AJCEM/1907 http://www.ajol.info/journals/ajcem COPYRIGHT 2018 https://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ajcem.v20i1.7 AFR. J. CLN. EXPER. MICROBIOL. 20 (1): 49-53 SURVEILLANCE OF ANTI-HCV ANTIBODY AMONGST IN-SCHOOL YOUTH IN A NIGERIA UNIVERSITY Muhibi M A 1, 2*, Ifeanyichukwu M O 2, Olawuyi A O 3, Abulude A A 2, Adeyemo M O 4, Muhibi M O 5 1 Haematology and Blood Transfusion Department, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology Teaching Hospital, Osogbo, Osun State, Nigeria; 2 Medical Laboratory Science Department, Nnamdi Azikwe University, Nnewi Campus, Anambra State, Nigeria.; 3 Chemical Pathology Department, Ekiti State University, Ado-Ekiti, Ekiti state, Nigeria; 4 Nursing Department, Osun State University, Osogbo, Osun State, Nigeria; 5 Health Information Management Department, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology Teaching Hospital, Osogbo, Osun State, Nigeria. Correspondence: Name: Muhibi M A, PMB 5000, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology Teaching Hospital, Osogbo, Osun State, Nigeria. E-mail: [email protected] Telephone: +2348033802694 ABSTRACT Infection with Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) is a public health problem. Worldwide, there are about 170 million people infected with HCV. HCV is transmitted through sex and use of contaminated sharp objects during tattooing or intravenous drug abuse. These routes make youth to be more vulnerable. Transfusion and mother to child transmissions are also documented modes. This study was carried out to determine sero-prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection among in school youth at Achievers University, Owo in southwest Nigeria. Samples of blood were collected from 70 undergraduate students and sera harvested were tested for the presence of antibodies against hepatitis C virus by Enzyme Immunoassay Technique. -

S/No State City/Town Provider Name Category Coverage Type Address

S/No State City/Town Provider Name Category Coverage Type Address 1 Abia AbaNorth John Okorie Memorial Hospital D Medical 12-14, Akabogu Street, Aba 2 Abia AbaNorth Springs Clinic, Aba D Medical 18, Scotland Crescent, Aba 3 Abia AbaSouth Simeone Hospital D Medical 2/4, Abagana Street, Umuocham, Aba, ABia State. 4 Abia AbaNorth Mendel Hospital D Medical 20, TENANT ROAD, ABA. 5 Abia UmuahiaNorth Obioma Hospital D Medical 21, School Road, Umuahia 6 Abia AbaNorth New Era Hospital Ltd, Aba D Medical 212/215 Azikiwe Road, Aba 7 Abia AbaNorth Living Word Mission Hospital D Medical 7, Umuocham Road, off Aba-Owerri Rd. Aba 8 Abia UmuahiaNorth Uche Medicare Clinic D Medical C 25 World Bank Housing Estate,Umuahia,Abia state 9 Abia UmuahiaSouth MEDPLUS LIMITED - Umuahia Abia C Pharmacy Shop 18, Shoprite Mall Abia State. 10 Adamawa YolaNorth Peace Hospital D Medical 2, Luggere Street, Yola 11 Adamawa YolaNorth Da'ama Specialist Hospital D Medical 70/72, Atiku Abubakar Road, Yola, Adamawa State. 12 Adamawa YolaSouth New Boshang Hospital D Medical Ngurore Road, Karewa G.R.A Extension, Jimeta Yola, Adamawa State. 13 Akwa Ibom Uyo St. Athanasius' Hospital,Ltd D Medical 1,Ufeh Street, Fed H/Estate, Abak Road, Uyo. 14 Akwa Ibom Uyo Mfonabasi Medical Centre D Medical 10, Gibbs Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State 15 Akwa Ibom Uyo Gateway Clinic And Maternity D Medical 15, Okon Essien Lane, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State. 16 Akwa Ibom Uyo Fulcare Hospital C Medical 15B, Ekpanya Street, Uyo Akwa Ibom State. 17 Akwa Ibom Uyo Unwana Family Hospital D Medical 16, Nkemba Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State 18 Akwa Ibom Uyo Good Health Specialist Clinic D Medical 26, Udobio Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State. -

Africana Studies Review

AFRICANA STUDIES REVIEW JOURNAL OF THE CENTER FOR AFRICAN AND AFRICAN AMERICAN STUDIES SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY AT NEW ORLEANS VOLUME 6 NUMBER 1 SPRING 2019 ON THE COVER DETAIL FROM A PIECE OF THE WOODEN QUILTS™ COLLECTION BY NEW ORLEANS- BORN ARTIST AND HOODOO MAN, JEAN-MARCEL ST. JACQUES. THE COLLECTION IS COMPOSED ENTIRELY OF WOOD SALVAGED FROM HIS KATRINA-DAMAGED HOME IN THE TREME SECTION OF THE CITY. ST. JACQUES CITES HIS GRANDMOTHER—AN AVID QUILTER—AND HIS GRANDFATHER—A HOODOO MAN—AS HIS PRIMARY INFLUENCES AND TELLS OF HOW HEARING HIS GRANDMOTHER’S VOICE WHISPER, “QUILT IT, BABY” ONE NIGHT INSPIRED THE ACCLAIMED COLLECTION. PIECES ARE NOW ON DISPLAY AT THE AMERICAN FOLK ART MUSEUM AND OTHER VENUES. READ MORE ABOUT ST. JACQUES’ JOURNEY BEGINNING ON PAGE 75 COVER PHOTOGRAPH BY DEANNA GLORIA LOWMAN AFRICANA STUDIES REVIEW JOURNAL OF THE CENTER FOR AFRICAN AND AFRICAN AMERICAN STUDIES SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY AT NEW ORLEANS VOLUME 6 NUMBER 1 SPRING 2019 ISSN 1555-9246 AFRICANA STUDIES REVIEW JOURNAL OF THE CENTER FOR AFRICAN AND AFRICAN AMERICAN STUDIES SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY AT NEW ORLEANS VOLUME 6 NUMBER 1 SPRING 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS About the Africana Studies Review ....................................................................... 4 Editorial Board ....................................................................................................... 5 Introduction to the Spring 2019 Issue .................................................................... 6 Funlayo E. Wood Menzies “Tribute”: Negotiating Social Unrest through African Diasporic Music and Dance in a Community African Drum and Dance Ensemble .............................. 11 Lisa M. Beckley-Roberts Still in the Hush Harbor: Black Religiosity as Protected Enclave in the Contemporary US ................................................................................................ 23 Nzinga Metzger The Tree That Centers the World: The Palm Tree as Yoruba Axis Mundi ........ -

A Perception Study of Development Control Activities in Ibadan, Osogbo and Ado-Ekiti

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Olowoporoku, Oluwaseun; Daramola, Oluwole; Agbonta, Wilson; Ogunleye, John Article Urban jumble in three Nigerian cities: A perception study of development control activities in Ibadan, Osogbo and Ado-Ekiti Economic and Environmental Studies (E&ES) Provided in Cooperation with: Opole University Suggested Citation: Olowoporoku, Oluwaseun; Daramola, Oluwole; Agbonta, Wilson; Ogunleye, John (2017) : Urban jumble in three Nigerian cities: A perception study of development control activities in Ibadan, Osogbo and Ado-Ekiti, Economic and Environmental Studies (E&ES), ISSN 2081-8319, Opole University, Faculty of Economics, Opole, Vol. 17, Iss. 4, pp. 795-811, http://dx.doi.org/10.25167/ees.2017.44.10 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/193043 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

World Rural Observations 2017;9(1) 32

World Rural Observations 2017;9(1) http://www.sciencepub.net/rural Commuting Pattern and Transportation Challenges in Akure Metropolis, Ondo State, Nigeria Gladys Chineze Emenike, Olabode Samson Ogunjobi Department of Geography and Environmental Management, University of Port Harcourt, Port Harcourt, Nigeria [email protected] Abstract: Many urban centers in Nigeria suffer from inadequate facilities that could ensure smooth urban movement. The increase in commuting distance has impact on trip attraction, fares paid by commuters, traffic build- up in some land use areas; and shows the need for different modes of transportation. The study examined the commuting pattern and transportation challenges in Akure Metropolis, Ondo State, Nigeria. A total number of 398 copies of structured questionnaire were distributed to commuters along the selected roads (Oyemekun road, Ondo road, Oba Ile road, Arakale road, Oke Aro road, Hospital road, Ijoka road, Oda road, Danjuma road, and Sijuade road). Data obtained were analysed using descriptive and inferential statistics. Findings showed that 52% were males and more than 70% of respondents were above 20 years. The mostly used type of transport in Akure City was public taxi (40.5%) and majority (49.7%) spent ≤ 30 minutes on the road before reaching their working place while the distance from home to work of more than 50% was ≤ 2km. The main trip purpose for commuters was education (33%) while most of the trips were made in the morning only (29.4%); and morning and evening (32.4%). However, 47.5% of commuters agreed that the peak hour of congestion is always between 7am and 9am. -

Evaluation of the Public Pipe-Borne Water Supply in Ilorin West Local Government Area of Kwara State, Nigeria

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Ibrahim, Rafiu Babatunde; Toyobo, Emmanuel Adigun; Adedotun, Samuel Babatunde; Yunus, Sulaiman Article Evaluation of the public pipe-borne water supply in Ilorin West Local Government Area of Kwara State, Nigeria Economic and Environmental Studies (E&ES) Provided in Cooperation with: Opole University Suggested Citation: Ibrahim, Rafiu Babatunde; Toyobo, Emmanuel Adigun; Adedotun, Samuel Babatunde; Yunus, Sulaiman (2018) : Evaluation of the public pipe-borne water supply in Ilorin West Local Government Area of Kwara State, Nigeria, Economic and Environmental Studies (E&ES), ISSN 2081-8319, Opole University, Faculty of Economics, Opole, Vol. 18, Iss. 3, pp. 1105-1118, http://dx.doi.org/10.25167/ees.2018.47.4 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/193132 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

Secondary Sex Ratio in a South-Western Nigerian Town

International Journal of Genetics ISSN: 0975-2862 & E-ISSN: 0975-9158, Volume 4, Issue 3, 2012, pp.-92-94. Available online at http://www.bioinfo.in/contents.php?id=25 SECONDARY SEX RATIO IN A SOUTH-WESTERN NIGERIAN TOWN TOLULOPE OYENIYI Department of Biological Sciences, College of Science, Engineering and Technology, Osun State University, Osogbo, Osun State, Nigeria. *Corresponding Author: Email- [email protected] Received: July 30, 2012; Accepted: August 06, 2012 Abstract- In this study, the human secondary sex ratio (described as the number of males per 100 female births) in Ondo, a town in South -West Nigeria was analyzed using birth record between 2001 and 2008, obtained at State Specialist Hospital. The analysis of the 11,426 births recorded during the period revealed a secondary sex ratio of 1.14, that is, 114 boys for every 100 girls born. There was a strong correlation (0.236**) between sex ratio and birth outcome indicating that gender has strong influence on child survival. There is however no significant relationship between the sex of baby and the season of birth as the ratio of male to female babies remains unchanged through the seasons. This study reports the first information on secondary sex ratio in Ondo town and gives impetus for further investigations into factors affecting secondary sex ratio among the populations at the study area. Key words- human secondary sex ratio, birth outcome, seasonality, Nigeria Citation: Tolulope Oyeniyi (2012) Secondary Sex Ratio in a South-Western Nigerian Town. International Journal of Genetics, ISSN: 0975- 2862 & E-ISSN: 0975-9158, Volume 4, Issue 3, pp.-92-94. -

States and Lcdas Codes.Cdr

PFA CODES 28 UKANEFUN KPK AK 6 CHIBOK CBK BO 8 ETSAKO-EAST AGD ED 20 ONUIMO KWE IM 32 RIMIN-GADO RMG KN KWARA 9 IJEBU-NORTH JGB OG 30 OYO-EAST YYY OY YOBE 1 Stanbic IBTC Pension Managers Limited 0021 29 URU OFFONG ORUKO UFG AK 7 DAMBOA DAM BO 9 ETSAKO-WEST AUC ED 21 ORLU RLU IM 33 ROGO RGG KN S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 10 IJEBU-NORTH-EAST JNE OG 31 SAKI-EAST GMD OY S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 2 Premium Pension Limited 0022 30 URUAN DUU AK 8 DIKWA DKW BO 10 IGUEBEN GUE ED 22 ORSU AWT IM 34 SHANONO SNN KN CODE CODE 11 IJEBU-ODE JBD OG 32 SAKI-WEST SHK OY CODE CODE 3 Leadway Pensure PFA Limited 0023 31 UYO UYY AK 9 GUBIO GUB BO 11 IKPOBA-OKHA DGE ED 23 ORU-EAST MMA IM 35 SUMAILA SML KN 1 ASA AFN KW 12 IKENNE KNN OG 33 SURULERE RSD OY 1 BADE GSH YB 4 Sigma Pensions Limited 0024 10 GUZAMALA GZM BO 12 OREDO BEN ED 24 ORU-WEST NGB IM 36 TAKAI TAK KN 2 BARUTEN KSB KW 13 IMEKO-AFON MEK OG 2 BOSARI DPH YB 5 Pensions Alliance Limited 0025 ANAMBRA 11 GWOZA GZA BO 13 ORHIONMWON ABD ED 25 OWERRI-MUNICIPAL WER IM 37 TARAUNI TRN KN 3 EDU LAF KW 14 IPOKIA PKA OG PLATEAU 3 DAMATURU DTR YB 6 ARM Pension Managers Limited 0026 S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 12 HAWUL HWL BO 14 OVIA-NORTH-EAST AKA ED 26 26 OWERRI-NORTH RRT IM 38 TOFA TEA KN 4 EKITI ARP KW 15 OBAFEMI OWODE WDE OG S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 4 FIKA FKA YB 7 Trustfund Pensions Plc 0028 CODE CODE 13 JERE JRE BO 15 OVIA-SOUTH-WEST GBZ ED 27 27 OWERRI-WEST UMG IM 39 TSANYAWA TYW KN 5 IFELODUN SHA KW 16 ODEDAH DED OG CODE CODE 5 FUNE FUN YB 8 First Guarantee Pension Limited 0029 1 AGUATA AGU AN 14 KAGA KGG BO 16 OWAN-EAST -

Factorial Causative Assesments and Effects of Building Construction

Adekunle and Ajibola, J Archit Eng Tech 2015, 4:3 al Eng tur ine ec er it in h g http://dx.doi.org/10.4172/2168-9717.1000150 c r T A e c f h o n l Architectural Engineering o a l n o r g u y o J ISSN: 2168-9717 Technology Research Article Open Access Factorial Causative Assesments and Effects of Building Construction Project Delays in Osun State, Nigeria Olusola Adekunle* and Kareem Ajibola W Department of Architectural Technology, Federal Polytechnic, Ede, Osun State, Nigeria Abstract Delay in building construction project is a universal phenomenon that is not peculiar to Osun alone. In fact, all countries of the world are faced with this global issue. These delays are usually considered as costly to all parties concerned in the projects and very often results in total abandonment thereby slowing down the growth of the construction sector. The purpose of this study was to assess the causative factors of delays and their effects on building construction projects in Osun. A total of forty two (42) project delay attributes and seventeen (17) effect attributes were identified through detailed literature review. Questionnaire survey were conducted across stakeholders that included among others; consultants, contractors and clients cutting across the building professionals namely; Architects, Builders, Quantity Surveyors, Estate Surveyors and Engineers to gather their views on causes of delay in delivery of projects. The research categorized the causes of delay under four main groups of client related, consultant related, contractor related and delay caused by incidental factors and their effects assessed using relative importance index (RII) as a basis for analysis. -

Inter-Trip Characteristics Model for Ado-Ekiti Township, Southwest Nigeria (Pp

An International Multi-Disciplinary Journal , Ethiopia Vol. 4 (2) April, 2010 ISSN 1994-9057 (Print) ISSN 2070-0083 (Online) Inter-Trip Characteristics Model for Ado-Ekiti Township, Southwest Nigeria (Pp. 1-14) Oyedepo, Olugbenga J. - Civil Engineering Department,Federal University of Technology, Akure, Nigeria. E mail: [email protected] Makinde, Oluyemisi O. - Civil Engineering Department,Rufus Giwa Polytechnic,Owo, Nigeria. E mail: [email protected] Abstract Travel characteristics survey and the useful time spent on road by commuters were collected from the terminals and members of National Union of Road Transport Workers. The survey also gave the travel behaviour of commuters and socio-economic characteristics over a period of time across the population. The analysis shows that a total of 7,338 Trips/per were made in Ado-Ekiti to various urban and rural area in which trip to Iworoko-Ekiti has the largest with 3,000 Trips per day. The regression analysis of travel time as dependent variable with other variables (travel cost and travel distance) gives average value of R and R 2 as 93.1% and 86.6% respectively. Keywords: Travel Behaviour, Terminals, Trips, and Socio-economic Characteristics Introduction Transport is an important element in the process of modernization, sometimes allowing and perhaps accelerating development and at other times acting as a brake in progress. Transport generally plays an important role for other factors of development i.e there is no escape from transport and this has Copyright © IAARR 2010: www.afrrevjo.com 1 Indexed African Journals Online: www.ajol.info African Research Review Vol. 4(2) April, 2010 .