Trends in Owo Traditional Sculptures: 1995 – 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Historical Survey of Socio-Political Administration in Akure Region up to the Contemporary Period

European Scientific Journal August edition vol. 8, No.18 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 A HISTORICAL SURVEY OF SOCIO-POLITICAL ADMINISTRATION IN AKURE REGION UP TO THE CONTEMPORARY PERIOD Afe, Adedayo Emmanuel, PhD Department of Historyand International Studies,AdekunleAjasin University,Akungba-Akoko, Ondo State, Nigeria Abstract Thepaper examines the political transformation of Akureregion from the earliest times to the present. The paper traces these stages of political development in order to demonstrate features associated with each stage. It argues further that pre-colonial Akure region, like other Yoruba regions, had a workable political system headed by a monarch. However, the Native Authority Ordinance of 1916, which brought about the establishment of the Native Courts and British judicial administration in the region led to the decline in the political power of the traditional institution.Even after independence, the traditional political institution has continually been subjugated. The work relies on both oral and written sources, which were critically examined. The paper, therefore,argues that even with its present political status in the contemporary Nigerian politics, the traditional political institution is still relevant to the development of thesociety. Keywords: Akure, Political, Social, Traditional and Authority Introduction The paper reviews the political administration ofAkure region from the earliest time to the present and examines the implication of the dynamics between the two periods may have for the future. Thus,assessment of the indigenous political administration, which was prevalent before the incursion of the colonial administration, the political administration during the colonial rule and the present political administration in the region are examined herein.However, Akure, in this context, comprises the present Akure North, Akure South, and Ifedore Local Government Areas of Ondo State, Nigeria. -

Mannitol Dosing Error During Pre-Neurosurgical Care of Head Injury: a Neurosurgical In-Hospital Survey from Ibadan, Nigeria

Published online: 2021-01-29 THIEME Original Article 171 Mannitol Dosing Error during Pre-neurosurgical Care of Head Injury: A Neurosurgical In-Hospital Survey from Ibadan, Nigeria Amos Olufemi Adeleye1,2 Toyin Ayofe Oyemolade2 Toluyemi Adefolarin Malomo2 Oghenekevwe Efe Okere2 1Department of Surgery, Division of Neurological Surgery, College Address for correspondence Amos Olufemi Adeleye, MBBS, of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria Department of Neurological Surgery, University College Hospital, 2Department of Neurological Surgery, University College Hospital, UCH, Ibadan, Owo, PMB 1053, Nigeria Ibadan, Nigeria (e-mail: [email protected]). J Neurosci Rural Pract:2021;12:171–176 Abstract Objectives Inappropriate use of mannitol is a medical error seen frequently in pre-neurosurgical head injury (HI) care that may result in serious adverse effects. This study explored this medical error amongst HI patients in a Nigerian neurosurgery unit. Methods We performed a cross-sectional analysis of a prospective cohort of HI patients who were administered mannitol by their initial non-neurosurgical health care givers before referral to our center over a 22-month period. Statistical Analysis A statistical software was used for the analysis with which an α value of <0.05 was deemed clinically significant. Results Seventy-one patients were recruited: 17 (23.9%) from private hospitals, 13 (18.3%) from primary health facilities (PHFs), 20 (28.2%) from secondary health facilities (SHFs), and 21 (29.6%) from tertiary health facilities (THFs). Thirteen patients (18.3%) had mild HI; 29 (40.8%) each had moderate and severe HI, respectively. Pupillary abnormalities were documented in five patients (7.04%) with severe HI and neurological deterioration in two with mild HI. -

ADJUSTMENT STYLES and EXPRESSION of POST-TRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDERS AMONG SELECTED POLICE in OSOGBO METROPOLIS Ajibade B.L1

International Journal of Health and Psychology Research Vol.6, No.2, pp.21-35, September 2018 ___Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) ADJUSTMENT STYLES AND EXPRESSION OF POST-TRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDERS AMONG SELECTED POLICE IN OSOGBO METROPOLIS Ajibade B.L1, Ayeni Adebusola Raphael2, Akao Olugbenga D1 and Omotoriogun M.I2 1Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, College of Health Sciences, Faculty of Clinical Sciences, Department of Nursing Science, Osogbo 2Achievers University, Department of Nursing Science, Owo ABSTRACT: This study explores the exposure to post-traumatic stress disorder among the police and expression of PTSD with the resultant adjustment strategies utilization to cope with PTSD. Descriptive survey research design was employed to select 200 respondents using simple random technique and Taro Yamane to determine the sample size. Self structured three sections questionnaire was used in data collection which lasted for the period of four months and descriptive statistics was used to analyse the collected data. The result revealed that the respondents mean age was 35.65±5.97 and majority of the respondents were men. The respondents expressed exposure to PSTD at various degree where “a little bit” on likert scale with mean value of 56.82±7.54. All the respondents adopted various adjustments strategies to combat PTSD which resulted in effective coping mechanism. In conclusion, the respondents’ ability to cope with post-traumatic stress disorders was in tandem with active middle age and readiness to defend the sovereignty of their nation. KEYWORDS: Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, Expression Adjustment Styles INTRODUCTION Policing necessitates exposure to traumatic, violent and horrific events, which can lead to an increased risk for developing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). -

Tropospheric and Atmospheric Physics; Nigerian Micrometeorological Experiment IPPS NIG:02

Tropospheric and Atmospheric Physics; IPPS NIG:02 Nigerian Micrometeorological Experiment Address Department of Physics Department of Meteorology Obafemi Awolowo University Federal University of Technology 220005 Ile-Ife P. M. B. 704 Nigeria Akure Nigeria Dept. of Physics Univ. of Ibadan Ibadan Nigeria Visiting address Road 12, House 21, Obafemi Awolowo University Staff Quarters Phone +234 803 473 0295 +234 703 007 7951 (J. B. Fax Omotosho, Akure) E-mail [email protected] +234 803 471 1147 (E. Oladiran, [email protected] Ibadan) [email protected] Group leader Prof J. A. Adedokun † (Ile Ife), Prof J. B. Omotosho (Akure) Prof E. O. Oladiran (Ibadan) Staff members Federal Univ. of Technology, Akure Obafemi Awolowi Univ: Prof J. B. Omotosho, PhD, Professor Prof J. A. Adedokun, PhD, Professor † Prof Z. D. Adyewa, PhD, Professor Prof O. O. Jegede, PhD, Professor Dr B. J. Abiodun, Lecturer Prof E. E. Balogun, PhD, Prof Emeritus Dr B. A. Adeyemi, Lecturer Dr M. A. Ayoola, M. Phil. Dr A. A, Balogun, Lecturer Ms T. O. Aregbesola, M. Phil. Dr E. O. Ogolo, Lecturer Ms G. O. Akinlade, MSc Dr K. O. Ogunjobi, Lecturer Mr E. O. Gbobaniyi, MSc Dr E. C. Okogbue, Lecturer Mr L. A. Sunmonu, MSc Dr O. R. Oladosu, Lecturer Mr E. O. Elemo, MSc Dr A. T. Adediji, PhD Mr O. J. Matthew, MSc Mr A. Oluleye, MSc. Mr A. Akinpelu, MSc Mr V. O. Ajayi, M. Tech. Mr O. O. Oni, MSc Mr A. Akinbobola, M. Tech. Mr O. E. Akinola, BSc Mr I. A. Balogun, M.Tech. Mr A. Oluleye, MSc Mr E. -

African Concepts of Energy and Their Manifestations Through Art

AFRICAN CONCEPTS OF ENERGY AND THEIR MANIFESTATIONS THROUGH ART A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Renée B. Waite August, 2016 Thesis written by Renée B. Waite B.A., Ohio University, 2012 M.A., Kent State University, 2016 Approved by ____________________________________________________ Fred Smith, Ph.D., Advisor ____________________________________________________ Michael Loderstedt, M.F.A., Interim Director, School of Art ____________________________________________________ John R. Crawford-Spinelli, D.Ed., Dean, College of the Arts TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES………………………………………….. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS …………………………………… vi CHAPTERS I. Introduction ………………………………………………… 1 II. Terms and Art ……………………………………………... 4 III. Myths of Origin …………………………………………. 11 IV. Social Structure …………………………………………. 20 V. Divination Arts …………………………………………... 30 VI. Women as Vessels of Energy …………………………… 42 VII. Conclusion ……………………………………….…...... 56 VIII. Images ………………………………………………… 60 IX. Bibliography …………………………………………….. 84 X. Further Reading ………………………………………….. 86 iii LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1: Porogun Quarter, Ijebu-Ode, Nigeria, 1992, Photograph by John Pemberton III http://africa.si.edu/exhibits/cosmos/models.html. ……………………………………… 60 Figure 2: Yoruba Ifa Divination Tapper (Iroke Ifa) Nigeria; Ivory. 12in, Baltimore Museum of Art http://www.artbma.org/. ……………………………………………… 61 Figure 3.; Yoruba Opon Ifa (Divination Tray), Nigerian; carved wood 3/4 x 12 7/8 x 16 in. Smith College Museum of Art, http://www.smith.edu/artmuseum/. ………………….. 62 Figure 4. Ifa Divination Vessel; Female Caryatid (Agere Ifa); Ivory, wood or coconut shell inlay. Nigeria, Guinea Coast The Metropolitan Museum of Art, http://www.metmuseum.org. ……………………… 63 Figure 5. Beaded Crown of a Yoruba King. Nigerian; L.15 (crown), L.15 (fringe) in. -

Ibadan, Nigeria by Laurent Fourchard

The case of Ibadan, Nigeria by Laurent Fourchard Contact: Source: CIA factbook Laurent Fourchard Institut Francais de Recherche en Afrique (IFRA), University of Ibadan Po Box 21540, Oyo State, Nigeria E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] INTRODUCTION: THE CITY A. URBAN CONTEXT 1. Overview of Nigeria: Economic and Social Trends in the 20th Century During the colonial period (end of the 19th century – agricultural sectors. The contribution of agriculture to 1960), the Nigerian economy depended mainly on agri- the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) fell from 60 percent cultural exports and on proceeds from the mining indus- in the 1960s to 31 percent by the early 1980s. try. Small-holder peasant farmers were responsible for Agricultural production declined because of inexpen- the production of cocoa, coffee, rubber and timber in the sive imports and heavy demand for construction labour Western Region, palm produce in the Eastern Region encouraged the migration of farm workers to towns and and cotton, groundnut, hides and skins in the Northern cities. Region. The major minerals were tin and columbite from From being a major agricultural net exporter in the the central plateau and from the Eastern Highlands. In 1960s and largely self-sufficient in food, Nigeria the decade after independence, Nigeria pursued a became a net importer of agricultural commodities. deliberate policy of import-substitution industrialisation, When oil revenues fell in 1982, the economy was left which led to the establishment of many light industries, with an unsustainable import and capital-intensive such as food processing, textiles and fabrication of production structure; and the national budget was dras- metal and plastic wares. -

Introduction Maintenance of the Security of Life and Property in Society Enhances Both Public Peace and Mutually Productive Ways of Life

Introduction Maintenance of the security of life and property in society enhances both public peace and mutually productive ways of life. With public peace achieved in society, a myriad of opportunities exist to create commercial and industrial openness and thereby attract productive entrepreneurs. The more secure productive entrepreneurs feel about their lives and property, the greater the confidence they have in receiving reasonable returns from their investments. Productive entrepreneurships are further enhanced when operational rules effectively lower transaction costs and thereby facilitate increasing possibilities for most participating individuals to reach more mutually acceptable contractual agreements. Economic development is more likely in such a political economy (North & Thomas 1976; de Soto 2000). Hardly can Yoruba communities accomplish this task without drawing upon love of equality, as envisioned by Tocqueville in Democracy in America. Principles of equality enable individuals to use their entrepreneurial inventiveness to evolve a living process of cooperation such that individuals can enjoy recognized rights to handle specific problems and opportunities and can join with other individuals in dealing with problems of general interest. When such ingenuity both takes cognizance of and is rooted in the shared values through which individuals with conflicting interests justify their political orders, most participating individuals are more likely to have a shared understanding about the security of their community as a common interest. In this regard, the level of public peace and order among the Yoruba of Nigeria will reflect how much shared understanding individuals have about the conceptions upon which the institutional arrangements for organizing their life are based. This is because "[t]he peace and security of a community is produced by the efforts of citizens...Collaboration between those who supply a service and those who use a service is essential if most public services are to yield the results desired" (V. -

Odo/Ota Local Government Secretariat, Sango - Agric

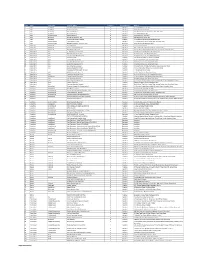

S/NO PLACEMENT DEPARTMENT ADO - ODO/OTA LOCAL GOVERNMENT SECRETARIAT, SANGO - AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 1 OTA, OGUN STATE AGEGE LOCAL GOVERNMENT, BALOGUN STREET, MATERNITY, AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 2 SANGO, AGEGE, LAGOS STATE AHMAD AL-IMAM NIG. LTD., NO 27, ZULU GAMBARI RD., ILORIN AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 3 4 AKTEM TECHNOLOGY, ILORIN, KWARA STATE AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 5 ALLAMIT NIG. LTD., IBADAN, OYO STATE AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 6 AMOULA VENTURES LTD., IKEJA, LAGOS STATE AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING CALVERTON HELICOPTERS, 2, PRINCE KAYODE, AKINGBADE MECHANICAL ENGINEERING 7 CLOSE, VICTORIA ISLAND, LAGOS STATE CHI-FARM LTD., KM 20, IBADAN/LAGOS EXPRESSWAY, AJANLA, AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 8 IBADAN, OYO STATE CHINA CIVIL ENGINEERING CONSTRUCTION CORPORATION (CCECC), KM 3, ABEOKUTA/LAGOS EXPRESSWAY, OLOMO - ORE, AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 9 OGUN STATE COCOA RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF NIGERIA (CRIN), KM 14, IJEBU AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 10 ODE ROAD, IDI - AYANRE, IBADAN, OYO STATE COKER AGUDA LOCAL COUNCIL, 19/29, THOMAS ANIMASAUN AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 11 STREET, AGUDA, SURULERE, LAGOS STATE CYBERSPACE NETWORK LTD.,33 SAKA TIINUBU STREET. AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 12 VICTORIA ISLAND, LAGOS STATE DE KOOLAR NIGERIA LTD.,PLOT 14, HAKEEM BALOGUN STREET, AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING OPP. TECHNICAL COLLEGE, AGIDINGBI, IKEJA, LAGOS STATE 13 DEPARTMENT OF PETROLEUM RESOURCES, 11, NUPE ROAD, OFF AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 14 AHMAN PATEGI ROAD, G.R.A, ILORIN, KWARA STATE DOLIGERIA BIOSYSTEMS NIGERIA LTD, 1, AFFAN COMPLEX, 1, AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 15 OLD JEBBA ROAD, ILORIN, KWARA STATE Page 1 SIWES PLACEMENT COMPANIES & ADDRESSES.xlsx S/NO PLACEMENT DEPARTMENT ESFOOS STEEL CONSTRUCTION COMPANY, OPP. SDP, OLD IFE AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 16 ROAD, AKINFENWA, EGBEDA, IBADAN, OYO STATE 17 FABIS FARMS NIGERIA LTD., ILORIN, KWARA STATE AGRIC. -

Surveillance of Anti-HCV Antibody Amongst In-School Youth in A

ORIGINAL ARTICLE AFRICAN JOURNAL OF CLINICAL AND EXPERIMENTAL MICROBIOLOGY ISBN 1595-689X JANUARY 2019 VOL20 No.1 AJCEM/1907 http://www.ajol.info/journals/ajcem COPYRIGHT 2018 https://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ajcem.v20i1.7 AFR. J. CLN. EXPER. MICROBIOL. 20 (1): 49-53 SURVEILLANCE OF ANTI-HCV ANTIBODY AMONGST IN-SCHOOL YOUTH IN A NIGERIA UNIVERSITY Muhibi M A 1, 2*, Ifeanyichukwu M O 2, Olawuyi A O 3, Abulude A A 2, Adeyemo M O 4, Muhibi M O 5 1 Haematology and Blood Transfusion Department, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology Teaching Hospital, Osogbo, Osun State, Nigeria; 2 Medical Laboratory Science Department, Nnamdi Azikwe University, Nnewi Campus, Anambra State, Nigeria.; 3 Chemical Pathology Department, Ekiti State University, Ado-Ekiti, Ekiti state, Nigeria; 4 Nursing Department, Osun State University, Osogbo, Osun State, Nigeria; 5 Health Information Management Department, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology Teaching Hospital, Osogbo, Osun State, Nigeria. Correspondence: Name: Muhibi M A, PMB 5000, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology Teaching Hospital, Osogbo, Osun State, Nigeria. E-mail: [email protected] Telephone: +2348033802694 ABSTRACT Infection with Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) is a public health problem. Worldwide, there are about 170 million people infected with HCV. HCV is transmitted through sex and use of contaminated sharp objects during tattooing or intravenous drug abuse. These routes make youth to be more vulnerable. Transfusion and mother to child transmissions are also documented modes. This study was carried out to determine sero-prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection among in school youth at Achievers University, Owo in southwest Nigeria. Samples of blood were collected from 70 undergraduate students and sera harvested were tested for the presence of antibodies against hepatitis C virus by Enzyme Immunoassay Technique. -

S/No State City/Town Provider Name Category Coverage Type Address

S/No State City/Town Provider Name Category Coverage Type Address 1 Abia AbaNorth John Okorie Memorial Hospital D Medical 12-14, Akabogu Street, Aba 2 Abia AbaNorth Springs Clinic, Aba D Medical 18, Scotland Crescent, Aba 3 Abia AbaSouth Simeone Hospital D Medical 2/4, Abagana Street, Umuocham, Aba, ABia State. 4 Abia AbaNorth Mendel Hospital D Medical 20, TENANT ROAD, ABA. 5 Abia UmuahiaNorth Obioma Hospital D Medical 21, School Road, Umuahia 6 Abia AbaNorth New Era Hospital Ltd, Aba D Medical 212/215 Azikiwe Road, Aba 7 Abia AbaNorth Living Word Mission Hospital D Medical 7, Umuocham Road, off Aba-Owerri Rd. Aba 8 Abia UmuahiaNorth Uche Medicare Clinic D Medical C 25 World Bank Housing Estate,Umuahia,Abia state 9 Abia UmuahiaSouth MEDPLUS LIMITED - Umuahia Abia C Pharmacy Shop 18, Shoprite Mall Abia State. 10 Adamawa YolaNorth Peace Hospital D Medical 2, Luggere Street, Yola 11 Adamawa YolaNorth Da'ama Specialist Hospital D Medical 70/72, Atiku Abubakar Road, Yola, Adamawa State. 12 Adamawa YolaSouth New Boshang Hospital D Medical Ngurore Road, Karewa G.R.A Extension, Jimeta Yola, Adamawa State. 13 Akwa Ibom Uyo St. Athanasius' Hospital,Ltd D Medical 1,Ufeh Street, Fed H/Estate, Abak Road, Uyo. 14 Akwa Ibom Uyo Mfonabasi Medical Centre D Medical 10, Gibbs Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State 15 Akwa Ibom Uyo Gateway Clinic And Maternity D Medical 15, Okon Essien Lane, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State. 16 Akwa Ibom Uyo Fulcare Hospital C Medical 15B, Ekpanya Street, Uyo Akwa Ibom State. 17 Akwa Ibom Uyo Unwana Family Hospital D Medical 16, Nkemba Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State 18 Akwa Ibom Uyo Good Health Specialist Clinic D Medical 26, Udobio Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State. -

BENIN-EKITI RELATION: an ONUS of SUBSTANTIATION Oluwaseun Samuel OSADOLA1, Michael EDIAGBONYA,2 Stephen Olayiwola SOETAN3

GSJ: Volume 7, Issue 2, February 2019 ISSN 2320-9186 403 GSJ: Volume 7, Issue 2, February 2019, Online: ISSN 2320-9186 www.globalscientificjournal.com BENIN-EKITI RELATION: AN ONUS OF SUBSTANTIATION Oluwaseun Samuel OSADOLA1, Michael EDIAGBONYA,2 Stephen Olayiwola SOETAN3 Abstract Pre-colonial times are characterized by the smooth and frequent relationship among societies. The nature of this relationship was mostly on the cultural, commercial and political ground. This, however, encourages inter-marriages, borrowing of languages and other features which were most times dictated by the needs of the various societies involved. Benin imperialism in Ekiti land is an aspect of cultural integration between the people of Benin and Ekiti. Although the nature of the alliance is said to have always run against the tide, it is, however, important to notice the impact of Benin's extension of influence in Ekiti land which brought about cultural integration between the two communities. This paper examines the various reasons of convergence between the Benin culture in one hand and the Ekiti people on the other side. It thus argues that Benin‟s expansion on some parts of Ekiti land has brought about cultural relations between them and that the administrative control which Benin had over them in one time or the other has encouraged these cultural similarities. The work relies on both primary and secondary sources and also employed descriptive and analytic methods in analyzing relevant data for the research. Keywords: Benin, Ekiti, Relationship, Cultural Similarities, 1 Ph.D. Candidate, Department of History and International Studies, Ekiti State University, Ado Ekiti, [email protected] 2 Ph.D. -

Changing Values of Traditional Marriage Among the Awori in Badagry Local Government

International Journal of Social & Management Sciences, Madonna University (IJSMS) Vol.1 No.1, March 2017; pg.131 – 138 CHANGING VALUES OF TRADITIONAL MARRIAGE AMONG THE AWORI IN BADAGRY LOCAL GOVERNMENT OLARINMOYE, ADEYINKA WULEMAT & ALIMI, FUNMILAYO SOFIYAT Department of Sociology, Lagos State University. Email address: [email protected] Abstract Some decades ago, it would have seemed absurd to question the significance of traditional marriage among the Awori-Yoruba of Southwestern Nigeria, as it was considered central to the organization of adult life. However, social change has far reaching effects on African traditional life. For instance, the increased social acceptance of pre-marital cohabitation, pre-marital sex and pregnancies and divorce is wide spread among the Yoruba people of today. This however appeared to have replaced the norms of traditional marriage; where marriage is now between two individuals and not families. This research uncovers what marriage values of the Yoruba were and how these values had been influenced overtime. The qualitative method of data collection was used. Data was collected and analyzed utilizing the content analysis and ethnographic summary techniques. The study revealed that modernization, education, mixture of cultures and languages, inter-marriage and electronic media have brought about changes in traditional marriage, along with consequences such as; drop in family standard, marriage instability, weak patriarchy system, and of values and customs. Despite the social changes, marriage remains significant value for individuals, families and in Yoruba society as a whole. Keywords: Traditional values, marriage, social change, Yoruba. INTRODUCTION The practice of marriage is apparently one of the most interesting aspects of human culture.