Ibadan, Nigeria by Laurent Fourchard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Informal Microfinance and Economic Activities of Rural Dwellers in Kwara South Senatorial District of Nigeria

International Journal of Business and Social Science Vol. 2 No. 15; August 2011 INFORMAL MICROFINANCE AND ECONOMIC ACTIVITIES OF RURAL DWELLERS IN KWARA SOUTH SENATORIAL DISTRICT OF NIGERIA IJAIYA, Muftau Adeniyi Department of Accounting and Finance University of Ilorin, Ilorin, Nigeria E-mail : [email protected], Phone: +2348036973561 Abstract Rural areas, like urban areas have increasing demand for credit because such credit reduces the impact of seasonality on incomes. However, formal financial institutions have maintained low presence in the rural areas. This has affected the rural dwellers’ access to deposit savings and credits that can improve their economic activities. This study examined the influence of informal microfinance on economic activities of rural dwellers in the selected rural areas of Kwara South Senatorial District. Using a multiple regression analysis, six hundred (600) questionnaire was administered on members of informal microfinance institution in the study area, the study found that fund provided as credit facilities for transaction purposes, funds for housing and combating diseases have significant influence on the economic activities of the rural areas. The study recommends group savings and group lending in order to increase savings and credits to the rural dwellers. Government should also provide improved infrastructural facilities that would enable rural dwellers have more access to their economic activities Key Words: Microfinance, Informal, Economic Activities, Rural, Kwara 1.0 Introduction Africa‟s development challenges go deeper than low income, falling trade shares, low savings and slow growth. They also include inequality and uneven access to productive resources, social exclusion and insecurity especially among the women (Pitamber, 2003). However, more specific concern is raised in Nigeria due to rural-urban disparities in income distribution, access to education and health care services, and prevalence of ethnic or cross-boundary conflicts. -

A Historical Survey of Socio-Political Administration in Akure Region up to the Contemporary Period

European Scientific Journal August edition vol. 8, No.18 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 A HISTORICAL SURVEY OF SOCIO-POLITICAL ADMINISTRATION IN AKURE REGION UP TO THE CONTEMPORARY PERIOD Afe, Adedayo Emmanuel, PhD Department of Historyand International Studies,AdekunleAjasin University,Akungba-Akoko, Ondo State, Nigeria Abstract Thepaper examines the political transformation of Akureregion from the earliest times to the present. The paper traces these stages of political development in order to demonstrate features associated with each stage. It argues further that pre-colonial Akure region, like other Yoruba regions, had a workable political system headed by a monarch. However, the Native Authority Ordinance of 1916, which brought about the establishment of the Native Courts and British judicial administration in the region led to the decline in the political power of the traditional institution.Even after independence, the traditional political institution has continually been subjugated. The work relies on both oral and written sources, which were critically examined. The paper, therefore,argues that even with its present political status in the contemporary Nigerian politics, the traditional political institution is still relevant to the development of thesociety. Keywords: Akure, Political, Social, Traditional and Authority Introduction The paper reviews the political administration ofAkure region from the earliest time to the present and examines the implication of the dynamics between the two periods may have for the future. Thus,assessment of the indigenous political administration, which was prevalent before the incursion of the colonial administration, the political administration during the colonial rule and the present political administration in the region are examined herein.However, Akure, in this context, comprises the present Akure North, Akure South, and Ifedore Local Government Areas of Ondo State, Nigeria. -

Mannitol Dosing Error During Pre-Neurosurgical Care of Head Injury: a Neurosurgical In-Hospital Survey from Ibadan, Nigeria

Published online: 2021-01-29 THIEME Original Article 171 Mannitol Dosing Error during Pre-neurosurgical Care of Head Injury: A Neurosurgical In-Hospital Survey from Ibadan, Nigeria Amos Olufemi Adeleye1,2 Toyin Ayofe Oyemolade2 Toluyemi Adefolarin Malomo2 Oghenekevwe Efe Okere2 1Department of Surgery, Division of Neurological Surgery, College Address for correspondence Amos Olufemi Adeleye, MBBS, of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria Department of Neurological Surgery, University College Hospital, 2Department of Neurological Surgery, University College Hospital, UCH, Ibadan, Owo, PMB 1053, Nigeria Ibadan, Nigeria (e-mail: [email protected]). J Neurosci Rural Pract:2021;12:171–176 Abstract Objectives Inappropriate use of mannitol is a medical error seen frequently in pre-neurosurgical head injury (HI) care that may result in serious adverse effects. This study explored this medical error amongst HI patients in a Nigerian neurosurgery unit. Methods We performed a cross-sectional analysis of a prospective cohort of HI patients who were administered mannitol by their initial non-neurosurgical health care givers before referral to our center over a 22-month period. Statistical Analysis A statistical software was used for the analysis with which an α value of <0.05 was deemed clinically significant. Results Seventy-one patients were recruited: 17 (23.9%) from private hospitals, 13 (18.3%) from primary health facilities (PHFs), 20 (28.2%) from secondary health facilities (SHFs), and 21 (29.6%) from tertiary health facilities (THFs). Thirteen patients (18.3%) had mild HI; 29 (40.8%) each had moderate and severe HI, respectively. Pupillary abnormalities were documented in five patients (7.04%) with severe HI and neurological deterioration in two with mild HI. -

Introduction Urban Reproductive Health

Family Planning Effort Index Ibadan, Ilorin, Abuja, and Kaduna FPE Nigeria 2011 Introduction Nigeria has a current population of 152 million with a growth rate of 3.2%, a Contraceptive Prevalence Rate (CPR) of 15.4 and a Total Fertility Rate (TFR) of 5.7. Nigeria plays an important role in the socio- political context of West Africa, since it constitutes 50.2% of the total population of the region (PRB 2009, DHS 2008). In response to the pattern of high growth rates, the National Policy on Population for Sustainable Development was launched in 2005. The policy recognized that population factors, social and economic development, and environmental issues are irrevocably interconnected and addressing them are critical to the achievement of sustainable development in Nigeria. The Nigerian population policy sets specific targets aimed at addressing high rates of population growth including a reduction in the annual national growth rate to 2% or lower by 2015, a reduction in the TFR of at least 0.6 children per woman every five years, and an increase in CPR of at least 2% points per year. However, Nigeria still has a 20% unmet need for family planning (NPC and ICF Macro, 2009). Family Planning was included in the fifth Millennium Development Goal (MDG) as an indicator for tracking progress of improving maternal health. This concept of integrating family planning with maternal health services is the same approach that the Nigerian Ministry of Health is utilizing with messages related to family planning highlighting the links between utilization and reduced maternal mortality. However, continuing low levels of CPR and high levels of maternal mortality highlight the importance of an increased emphasis on family planning both within the context of maternal health and other health and social benefits. -

Prof. Dr. Kayode AJAYI Dr. Muyiwa ADEYEMI Faculty of Education Olabisi Onabanjo University, Ago-Iwoye, NIGERIA

International Journal on New Trends in Education and Their Implications April, May, June 2011 Volume: 2 Issue: 2 Article: 4 ISSN 1309-6249 UNIVERSAL BASIC EDUCATION (UBE) POLICY IMPLEMENTATION IN FACILITIES PROVISION: Ogun State as a Case Study Prof. Dr. Kayode AJAYI Dr. Muyiwa ADEYEMI Faculty of Education Olabisi Onabanjo University, Ago-Iwoye, NIGERIA ABSTRACT The Universal Basic Education Programme (UBE) which encompasses primary and junior secondary education for all children (covering the first nine years of schooling), nomadic education and literacy and non-formal education in Nigeria have adopted the “collaborative/partnership approach”. In Ogun State, the UBE Act was passed into law in 2005 after that of the Federal government in 2004, hence, the demonstration of the intention to make the UBE free, compulsory and universal. The aspects of the policy which is capital intensive require the government to provide adequately for basic education in the area of organization, funding, staff development, facilities, among others. With the commencement of the scheme in 1999/2000 until-date, Ogun State, especially in the area of facility provision, has joined in the collaborative effort with the Federal government through counter-part funding to provide some facilities to schools in the State, especially at the Primary level. These facilities include textbooks (in core subjects’ areas- Mathematics, English, Social Studies and Primary Science), blocks of classrooms, furniture, laboratories/library, teachers, etc. This study attempts to assess the level of articulation by the Ogun State Government of its UBE policy within the general framework of the scheme in providing facilities to schools at the primary level. -

AUTHOR TITLE Adult Forces

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 059 416 AC 012 155 AUTHOR Nasution, Amir H. TITLE Foreign Assistance Contribution in AdultEducation in Nigeria. INSTITUTION Ibadan Univ. (Nigeria). Inst. of AfricanAdult Education. PUB DATE Mar 71 NOTE 25p.; Paper presented to Nigerial NationalConference on Adult Education (March25-27, 1971, Lagos Univ., Lagos) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS Administrative Personnel; *Adult Education;Community Agencies (Public) ;*Conferences; *Cooperative Programs; *Educational Finance; EducationalNeeds; Federal Programs; *Financial Support;*Foreign Countries; Group Activities; Mass Instruction; Organizations (Groups); Planning; PrivateAgencies; State Programs IDENTIFIERS Af r ica; *Nigeria ABSTRACT The proceedings of a nation-wideconference in Nigeria concerning adult education arepresented. The following steps are proposed in the line ofnational and international cooperation; these steps can be taken without waitingfor financial and administrative approval:(1) the registration of all kinds ofadult education programs and activities carried outby public as well as private agencies;(2) involvement of all educationpersonnel in the planning organization, and establishment of anEducation Planning Unit; (3) the formation of adult educationpriority programs, with supporting services, mass education meansand libraries, to be assisted in the context of Federal and Statesset of priorities and potentialities; and (4)the mobilization of private funds andforces on behalf of adult education.(Author/CK) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEENREPRO- DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVEDFROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATIONORIG- INATING IT. POINTS OF VIEW OR OPIN- IONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OFEDU- CATION POSITION OR POLICY. C) e--I FORE'IGNASSISTANCE CONTRIBUTION. I N LC\ ADULT EDUCATION IN NIGERIA LIJ By Amir H. -

Rainfall and the Length of the Growing Season in Nigeria

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CLIMATOLOGY Int. J. Climatol. 24: 467–479 (2004) Published online in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com). DOI: 10.1002/joc.1012 RAINFALL AND THE LENGTH OF THE GROWING SEASON IN NIGERIA T. O. ODEKUNLE* Department of Geography, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria Received 15 May 2003 Revised 8 December 2003 Accepted 16 December 2003 ABSTRACT This study examines the length of the growing season in Nigeria using the daily rainfall data of Ikeja, Ondo, Ilorin, Kaduna and Kano. The data were collected from the archives of the Nigerian Meteorological Services, Oshodi, Lagos. The length of the growing season was determined using the cumulative percentage mean rainfall and daily rainfall probability methods. Although rainfall in Ikeja, Ondo, Ilorin, Kaduna, and Kano appears to commence around the end of the second dekad of March, middle of the third dekad of March, mid April, end of the first dekad of May, and early June respectively, its distribution characteristics at the respective stations remain inadequate for crop germination, establishment, and development till the end of the second dekad of May, early third dekad of May, mid third dekad of May, end of May, and end of the first dekad of July respectively. Also, rainfall at the various stations appears to retreat starting from the early third dekad of October, early third dekad of October, end of the first dekad of October, end of September, and early second dekad of September respectively, but its distribution characteristics only remain adequate for crop development at the respective stations till around the end of the second dekad of October, end of the second dekad of October, middle of the first dekad of October, early October, and middle of the first dekad of September respectively. -

Rail Transportation Data

Rail Transportation Data (Q1 2019) Report Date: May 2019 Data Source: National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) Contents Executive Summary 1 Number of Passengers 2 Volume of Goods/Cargo (Tons) 3 Revenue Generated from Passenger (N) 4 Revenue Generated from Goods/Cargo (N) 5 Other Income Receipt (N) 6 Methodology 7 Definition of Terms 8 Appendix 9 Acknowledgment and Contact 10 Executive Summary The rail transportation data for Q1 2019 reflected that a total of 723,995 passengers travelled via the rail system in Q1 2019 as against 748,345 passenger recorded in Q1 2018 and 746,739 in Q4 2018 representing -3.25% decline YoY and -3.05% decline QoQ respectively. Similarly, a total of 54,099 tons of volume of goods/cargo travelled via the rail system in Q1 2019 as against 79,750 recorded in Q1 2018 and 68,716 in Q4 2018 representing -32.16% decline YoY and -21.27% decline QoQ respectively. Revenue generated from passengers in Q1 2019 was put at N520,794,143 as against N507,495,503 in Q4 2018. Similarly, revenue generated from goods/cargo in Q1 2019 was put at N102,585,926 as against N84,408,861 in Q4 2018. 1 Rail Transportation Data - Q1 2019 Rail Transportation Data - Q1 2019 Number of Passengers 2019 Q on Q Y on Y % Change QRT 1 % Change (3.05) 723,995 (3.25) 2018 QRT 1 QRT 2 QRT 3 QRT 4 748,345 730,289 794,316 746,739 TOTAL 3,019,689 12 Rail Transportation Data - Q1 2019 Rail Transportation Data - Q1 2019 Volume of Goods/Cargo (Tons) 2019 Q on Q Y on Y % Change QRT 1 % Change (21.27) 54,099 (32.16) 2018 QRT 1 QRT 2 QRT 3 QRT 4 79,750 85,816 94,352 -

AFRREV STECH, Vol. 3(2) May, 2014

AFRREV STECH, Vol. 3(2) May, 2014 AFRREV STECH An International Journal of Science and Technology Bahir Dar, Ethiopia Vol. 3 (2), S/No 7, May, 2014: 51-65 ISSN 2225-8612 (Print) ISSN 2227-5444 (Online) http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/stech.v3i2.4 THE USE OF COMPOSITE WATER POVERTY INDEX IN ASSESSING WATER SCARCITY IN THE RURAL AREAS OF OYO STATE, NIGERIA IFABIYI, IFATOKUN PAUL Department of Geography and Environmental Management, Faculty of Social Sciences University of Ilorin; Ilorin, Kwara State, Nigeria E-mail: 234 8033231626 & OGUNBODE, TIMOTHY OYEBAMIJI Faculty of Law Bowen University, Iwo Osun State, Nigeria Abstract Physical availability of water resources is beneficial to man when it is readily accessible. Oyo State is noted for abundant surface water and appreciable groundwater resources in its pockets of regolith aquifers; as it has about eight months of rainy season and a relatively deep weathered regolith. In spite of this, cases of water associated diseases Copyright© IAARR 2014: www.afrrevjo.net 51 Indexed and Listed in AJOL, ARRONET AFRREV STECH, Vol. 3(2) May, 2014 and deaths have been reported in the rural areas of the state. This study attempts to conduct an investigation into accessibility to potable water in the rural areas of Oyo State, Nigeria via the component approach of water poverty index (WPI). Multistage method of sampling was applied to select 5 rural communities from 25 rural LGAs out of the 33 LGAs in the State. Data were collected through the administration of 1,250 copies of questionnaire across 125 rural communities. Component Index method as developed by Sullivan, et al (2003) was modified and used in this study. -

Nigeria Update to the IMB Nigeria

Progress in Polio Eradication Initiative in Nigeria: Challenges and Mitigation Strategies 16th Independent Monitoring Board Meeting 1 November 2017 London 0 Outline 1. Epidemiology 2. Challenges and Mitigation strategies SIAs Surveillance Routine Immunization 3. Summary and way forward 1 Epidemiology 2 Polio Viruses in Nigeria, 2015-2017 Past 24 months Past 12 months 3 Nigeria has gone 13 months without Wild Polio Virus and 11 months without cVDPV2 13 months without WPV 11 months – cVDPV2 4 Challenges and Mitigation strategies 5 SIAs 6 Before the onset of the Wild Polio Virus Outbreak in July 2016, there were several unreached settlements in Borno Borno Accessibility Status by Ward, March 2016 # of Wards in % Partially LGAs % Fully Accessible % Inaccessible LGA Accessible Abadam 10 0% 0% 100% Askira-Uba 13 100% 0% 0% Bama 14 14% 0% 86% Bayo 10 100% 0% 0% Biu 11 91% 9% 0% Chibok 11 100% 0% 0% Damboa 10 20% 0% 80% Dikwa 10 10% 0% 90% Gubio 10 50% 10% 40% Guzamala 10 0% 0% 100% Gwoza 13 8% 8% 85% Hawul 12 83% 17% 0% Jere 12 50% 50% 0% Kaga 15 0% 7% 93% Kala-Balge 10 0% 0% 100% Konduga 11 0% 64% 36% Kukawa 10 20% 0% 80% Kwaya Kusar 10 100% 0% 0% Mafa 12 8% 0% 92% Magumeri 13 100% 0% 0% Maiduguri 15 100% 0% 0% Marte 13 0% 0% 100% Mobbar 10 0% 0% 100% Monguno 12 8% 0% 92% Ngala 11 0% 0% 100% Nganzai 12 17% 0% 83% Shani 11 100% 0% 0% State 311 41% 6% 53% 7 Source: Borno EOC Data team analysis Four Strategies were deployed to expand polio vaccination reach and increase population immunity in Borno state SIAs RES2 RIC4 Special interventions 12 -

Ijebu-Ode Ile-Ife Truck Road South- West Nigeria

Ijebu-Ode Ile-Ife Truck Road South- West Nigeria. Client: Federal Ministry of Works Lagos- Nigeria. Location: Osun- Ogun State - Nigeria. Date: 1977 The Nigerian Federal Ministry of Works commissioned Allott (Nigeria) Limited to undertake the location, survey and detailed design of a new trunk road to link the towns of Ijebu Ode Ile-Ife and Sekona which lie to the north of Lagos and south east of Ibadan. The route over which this road was to pass was through thick tropical rain forest and sparsely populated. Access was difficult and the existing dirt roads were impassable in the rainy season. A suitable was located from a study of aerial photography and a ground reconnaissance which was followed by a traverse survey. The detailed design of the road’s alignment was carried out using the latest computer-aided techniques, further to the results of the topographical survey. Other field work Included a hydrological survey and a borehole survey. On completion of the design, the centre line of the new road was staked out by the field team. The proposed road had a two lane carriageway with bituminous surfacing, a crushed stone base and a laterite sub- base. The total length was 140km and there were a total of 13 bridges. The two major structures were the 150m long 6-span bridge over the River Oshun and the 75m long 3-span bridge over the River Shasha. These have in-situ reinforced concrete voided decks supported on reinforced concrete piers. The location of sources of suitable road Construction materials was an important part of the design. -

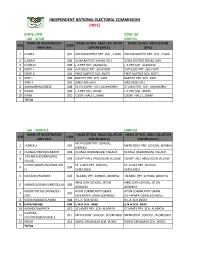

State: Oyo Code: 30 Lga : Afijio Code: 01 Name of Registration Name of Reg

INDEPENDENT NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION (INEC) STATE: OYO CODE: 30 LGA : AFIJIO CODE: 01 NAME OF REGISTRATION NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE AREA (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 ILORA I 001 OKEDIJI BAPTIST PRY. SCH., ILORA OKEDIJI BAPTIST PRY. SCH., ILORA 2 ILORA II 002 ILORA BAPTIST GRAM. SCH. ILORA BAPTIST GRAM. SCH. 3 ILORA III 003 L.A PRY SCH. ALAWUSA. L.A PRY SCH. ALAWUSA. 4 FIDITI I 004 CATHOLIC PRY. SCH FIDITI CATHOLIC PRY. SCH FIDITI 5 FIDITI II 005 FIRST BAPTIST SCH. FIDITI FIRST BAPTIST SCH. FIDITI 6 AWE I 006 BAPTIST PRY. SCH. AWE BAPTIST PRY. SCH. AWE 7 AWE II 007 AWE HIGH SCH. AWE HIGH SCH. 8 AKINMORIN/JOBELE 008 ST.JOHN PRY. SCH. AKINMORIN ST.JOHN PRY. SCH. AKINMORIN 9 IWARE 009 L.A PRY SCH. IWARE. L.A PRY SCH. IWARE. 10 IMINI 010 COURT HALL 1, IMINI COURT HALL 1, IMINI TOTAL LGA : AKINYELE CODE: 02 NAME OF REGISTRATION NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION S/N CODE AREA (RA) CENTRE (RACC) CENTRE (RACC) METHODIST PRY. SCHOOL, 1 IKEREKU 001 METHODIST PRY. SCHOOL, IKEREKU IKEREKU 2 OLANLA/OBODA/LABODE 002 OLANLA (OGBANGAN) VILLAGE OLANLA (OGBANGAN) VILLAGE EOLANLA (OGBANGAN) 3 003 COURT HALL ARULOGUN VILLAGE COURT HALL ARULOGUN VILLAGE VILLAG OLODE/AMOSUN/ONIDUND ST. LUKES PRY. SCHOOL, ST. LUKES PRY. SCHOOL, 4 004 U ONIDUNDU ONIDUNDU 5 OJO-EMO/MONIYA 005 ISLAMIC PRY. SCHOOL, MONIYA ISLAMIC PRY. SCHOOL, MONIYA ANGLICAN SCHOOL, OTUN ANGLICAN SCHOOL, OTUN 6 AKINYELE/ISABIYI/IREPODUN 006 AGBAKIN AGBAKIN IWOKOTO/TALONTAN/IDI- AYUN COMMUNITY GRAM.