Art in Ancient Ife, Birthplace of the Yoruba

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction: Introducing Yemoja

1 2 3 4 5 Introduction 6 7 8 Introducing Yemoja 9 10 11 12 Solimar Otero and Toyin Falola 13 14 15 16 17 18 Mother I need 19 mother I need 20 mother I need your blackness now 21 as the august earth needs rain. 22 —Audre Lorde, “From the House of Yemanjá”1 23 24 “Yemayá es Reina Universal porque es el Agua, la salada y la dul- 25 ce, la Mar, la Madre de todo lo creado / Yemayá is the Universal 26 Queen because she is Water, salty and sweet, the Sea, the Mother 27 of all creation.” 28 —Oba Olo Ocha as quoted in Lydia Cabrera’s Yemayá y Ochún.2 29 30 31 In the above quotes, poet Audre Lorde and folklorist Lydia Cabrera 32 write about Yemoja as an eternal mother whose womb, like water, makes 33 life possible. They also relate in their works the shifting and fluid nature 34 of Yemoja and the divinity in her manifestations and in the lives of her 35 devotees. This book, Yemoja: Gender, Sexuality, and Creativity in the 36 Latina/o and Afro-Atlantic Diasporas, takes these words of supplica- 37 tion and praise as an entry point into an in-depth conversation about 38 the international Yoruba water deity Yemoja. Our work brings together 39 the voices of scholars, practitioners, and artists involved with the inter- 40 sectional religious and cultural practices involving Yemoja from Africa, 41 the Caribbean, North America, and South America. Our exploration 42 of Yemoja is unique because we consciously bridge theory, art, and 43 xvii SP_OTE_INT_xvii-xxxii.indd 17 7/9/13 5:13 PM xviii Solimar Otero and Toyin Falola 1 practice to discuss orisa worship3 within communities of color living in 2 postcolonial contexts. -

A Historical Survey of Socio-Political Administration in Akure Region up to the Contemporary Period

European Scientific Journal August edition vol. 8, No.18 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 A HISTORICAL SURVEY OF SOCIO-POLITICAL ADMINISTRATION IN AKURE REGION UP TO THE CONTEMPORARY PERIOD Afe, Adedayo Emmanuel, PhD Department of Historyand International Studies,AdekunleAjasin University,Akungba-Akoko, Ondo State, Nigeria Abstract Thepaper examines the political transformation of Akureregion from the earliest times to the present. The paper traces these stages of political development in order to demonstrate features associated with each stage. It argues further that pre-colonial Akure region, like other Yoruba regions, had a workable political system headed by a monarch. However, the Native Authority Ordinance of 1916, which brought about the establishment of the Native Courts and British judicial administration in the region led to the decline in the political power of the traditional institution.Even after independence, the traditional political institution has continually been subjugated. The work relies on both oral and written sources, which were critically examined. The paper, therefore,argues that even with its present political status in the contemporary Nigerian politics, the traditional political institution is still relevant to the development of thesociety. Keywords: Akure, Political, Social, Traditional and Authority Introduction The paper reviews the political administration ofAkure region from the earliest time to the present and examines the implication of the dynamics between the two periods may have for the future. Thus,assessment of the indigenous political administration, which was prevalent before the incursion of the colonial administration, the political administration during the colonial rule and the present political administration in the region are examined herein.However, Akure, in this context, comprises the present Akure North, Akure South, and Ifedore Local Government Areas of Ondo State, Nigeria. -

Yoruba Art & Culture

Yoruba Art & Culture Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology University of California, Berkeley Yoruba Art and Culture PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Written and Designed by Nicole Mullen Editors Liberty Marie Winn Ira Jacknis Special thanks to Tokunbo Adeniji Aare, Oduduwa Heritage Organization. COPYRIGHT © 2004 PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY AND THE REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY ◆ UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT BERKELEY BERKELEY, CA 94720-3712 ◆ 510-642-3682 ◆ HTTP://HEARSTMUSEUM.BERKELEY.EDU Table of Contents Vocabulary....................4 Western Spellings and Pronunciation of Yoruba Words....................5 Africa....................6 Nigeria....................7 Political Structure and Economy....................8 The Yoruba....................9, 10 Yoruba Kingdoms....................11 The Story of How the Yoruba Kingdoms Were Created....................12 The Colonization and Independence of Nigeria....................13 Food, Agriculture and Trade....................14 Sculpture....................15 Pottery....................16 Leather and Beadwork....................17 Blacksmiths and Calabash Carvers....................18 Woodcarving....................19 Textiles....................20 Religious Beliefs....................21, 23 Creation Myth....................22 Ifa Divination....................24, 25 Music and Dance....................26 Gelede Festivals and Egugun Ceremonies....................27 Yoruba Diaspora....................28 -

Mannitol Dosing Error During Pre-Neurosurgical Care of Head Injury: a Neurosurgical In-Hospital Survey from Ibadan, Nigeria

Published online: 2021-01-29 THIEME Original Article 171 Mannitol Dosing Error during Pre-neurosurgical Care of Head Injury: A Neurosurgical In-Hospital Survey from Ibadan, Nigeria Amos Olufemi Adeleye1,2 Toyin Ayofe Oyemolade2 Toluyemi Adefolarin Malomo2 Oghenekevwe Efe Okere2 1Department of Surgery, Division of Neurological Surgery, College Address for correspondence Amos Olufemi Adeleye, MBBS, of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria Department of Neurological Surgery, University College Hospital, 2Department of Neurological Surgery, University College Hospital, UCH, Ibadan, Owo, PMB 1053, Nigeria Ibadan, Nigeria (e-mail: [email protected]). J Neurosci Rural Pract:2021;12:171–176 Abstract Objectives Inappropriate use of mannitol is a medical error seen frequently in pre-neurosurgical head injury (HI) care that may result in serious adverse effects. This study explored this medical error amongst HI patients in a Nigerian neurosurgery unit. Methods We performed a cross-sectional analysis of a prospective cohort of HI patients who were administered mannitol by their initial non-neurosurgical health care givers before referral to our center over a 22-month period. Statistical Analysis A statistical software was used for the analysis with which an α value of <0.05 was deemed clinically significant. Results Seventy-one patients were recruited: 17 (23.9%) from private hospitals, 13 (18.3%) from primary health facilities (PHFs), 20 (28.2%) from secondary health facilities (SHFs), and 21 (29.6%) from tertiary health facilities (THFs). Thirteen patients (18.3%) had mild HI; 29 (40.8%) each had moderate and severe HI, respectively. Pupillary abnormalities were documented in five patients (7.04%) with severe HI and neurological deterioration in two with mild HI. -

Introduction Urban Reproductive Health

Family Planning Effort Index Ibadan, Ilorin, Abuja, and Kaduna FPE Nigeria 2011 Introduction Nigeria has a current population of 152 million with a growth rate of 3.2%, a Contraceptive Prevalence Rate (CPR) of 15.4 and a Total Fertility Rate (TFR) of 5.7. Nigeria plays an important role in the socio- political context of West Africa, since it constitutes 50.2% of the total population of the region (PRB 2009, DHS 2008). In response to the pattern of high growth rates, the National Policy on Population for Sustainable Development was launched in 2005. The policy recognized that population factors, social and economic development, and environmental issues are irrevocably interconnected and addressing them are critical to the achievement of sustainable development in Nigeria. The Nigerian population policy sets specific targets aimed at addressing high rates of population growth including a reduction in the annual national growth rate to 2% or lower by 2015, a reduction in the TFR of at least 0.6 children per woman every five years, and an increase in CPR of at least 2% points per year. However, Nigeria still has a 20% unmet need for family planning (NPC and ICF Macro, 2009). Family Planning was included in the fifth Millennium Development Goal (MDG) as an indicator for tracking progress of improving maternal health. This concept of integrating family planning with maternal health services is the same approach that the Nigerian Ministry of Health is utilizing with messages related to family planning highlighting the links between utilization and reduced maternal mortality. However, continuing low levels of CPR and high levels of maternal mortality highlight the importance of an increased emphasis on family planning both within the context of maternal health and other health and social benefits. -

As an Expression of Yorùbá Aesthetic Philosophy

ISSN 2039-2117 (online) Mediterranean Journal of Vol 9 No 4 ISSN 2039-9340 (print) Social Sciences July 2018 Research Article © 2018 Ajíbóyè et.al.. This is an open access article licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/). Orí (Head) as an Expression of Yorùbá Aesthetic Philosophy Olusegun Ajíbóyè Stephen Fọlárànmí Nanashaitu Umoru-Ọ̀ kẹ Department of Fine and Applied Arts, Obafemi Awólọ́ wọ University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria Doi: 10.2478/mjss-2018-0115 Abstract Aesthetics was never a subject or a separate philosophy in the traditional philosophies of black Africa. This is however not a justification to conclude that it is nonexistent. Indeed, aesthetics is a day to day affair among Africans. There are criteria for aesthetic judgment among African societies which vary from one society to the other. The Yorùbá of Southwestern Nigeria are not different. This study sets out to examine how the Yorùbá make their aesthetic judgments and demonstrate their aesthetic philosophy in decorating their orí, which means head among the Yorùbá. The head receives special aesthetic attention because of its spiritual and biological importance. It is an expression of the practicalities of Yorùbá aesthetic values. Literature and field work has been of paramount aid to this study. The study uses photographs, works of art and visual illustrations to show the various ways the head is adorned and cared for among the Yoruba. It relied on Yoruba art and language as a tool of investigating the concept of ori and aesthetics. Yorùbá aesthetic values are practically demonstrable and deeply located in the Yorùbá societal, moral and ethical idealisms. -

A Critical Analysis of Marital Instability Among Yoruba Christian Couples In

A Critical Analysis of Marital Instability among Yoruba Christian Couples in the North West of England By Philip Bukola Oyewale A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Department of Theology, Philosophy and Religious Studies, Liverpool Hope University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (Theology) Liverpool, UK August 2016 1 Declaration I, Philip Oyewale, declare that this thesis is my original research and has not been submitted previously for another degree or qualification of this or any other university or other institute of learning. All published and unpublished works cited are duly referenced and acknowledged. Philip Oyewale 2 Abstract Marriage, as understood from the Christian, Nigerian Baptist Convention‟s, perspective, is a mutual relationship endorsed by holy matrimony between a consenting man and a woman. Similarly, within the Nigerian socio-cultural setting, particularly among the Yoruba, marriage is recognized and endorsed as sacred and accorded great priority. To the Yoruba, it signifies a crucial rite of passage, a transition to adulthood and immense responsibilities within the community. However, despite the sanctity and lofty views of marriage, a number of Diaspora Yoruba Christians couples living in the North West of England (NWE) are increasingly experiencing serious marital instability and conflict. This thesis, therefore, critically examines Yoruba couples „understanding of marriage and how their various contacts with social realities in the NWE impact upon spousal relations. Particular attention is paid to cross-cultural factors, power structures among the Yoruba and social structures that promote Yoruba women‟s empowerment in the NWE. The study employs semi-structured qualitative interviews. -

Activating the Past

Activating the Past Activating the Past: History and Memory in the Black Atlantic World Edited by Andrew Apter and Lauren Derby Activating the Past: History and Memory in the Black Atlantic World, Edited by Andrew Apter and Lauren Derby This book first published 2010 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2010 by Andrew Apter and Lauren Derby and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-1638-8, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-1638-0 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures and Tables ......................................................................... vii Acknowledgements .................................................................................... xi Introduction .............................................................................................. xiii Andrew Apter and Lauren Derby Chapter One......................................................................................................... 1 Ekpe/Abakuá in Middle Passage: Time, Space and Units of Analysis in African American Historical Anthropology Stephan Palmié Chapter Two............................................................................................. -

The House of Oduduwa: an Archaeological Study of Economy and Kingship in the Savè Hills of West Africa

The House of Oduduwa: An Archaeological Study of Economy and Kingship in the Savè Hills of West Africa by Andrew W. Gurstelle A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Professor Carla M. Sinopoli, Chair Professor Joyce Marcus Professor Raymond A. Silverman Professor Henry T. Wright © Andrew W. Gurstelle 2015 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I must first and foremost acknowledge the people of the Savè hills that contributed their time, knowledge, and energies. Completing this dissertation would not have been possible without their support. In particular, I wish to thank Ọba Adétùtú Onishabe, Oyedekpo II Ọla- Amùṣù, and the many balè,̣ balé, and balọdè ̣that welcomed us to their communities and facilitated our research. I also thank the many land owners that allowed us access to archaeological sites, and the farmers, herders, hunters, fishers, traders, and historians that spoke with us and answered our questions about the Savè hills landscape and the past. This dissertion was truly an effort of the entire community. It is difficult to express the depth of my gratitude for my Béninese collaborators. Simon Agani was with me every step of the way. His passion for Shabe history inspired me, and I am happy to have provided the research support for him to finish his research. Nestor Labiyi provided support during crucial periods of excavation. As with Simon, I am very happy that our research interests complemented and reinforced one another’s. Working with Travis Williams provided a fresh perspective on field methods and strategies when it was needed most. -

“YORUBA's DON't DO GENDER”: a CRITICAL REVIEW of OYERONKE OYEWUMI's the Invention of Women

“YORUBA’S DON’T DO GENDER”: A CRITICAL REVIEW OF OYERONKE OYEWUMI’s The Invention of Women: Making an African Sense of Western Gender Discourses By Bibi Bakare-Yusuf Discourses on Africa, especially those refracted through the prism of developmentalism, promote gender analysis as indispensable to the economic and political development of the African future. Conferences, books, policies, capital, energy and careers have been made in its name. Despite this, there has been very little interrogation of the concept in terms of its relevance and applicability to the African situation. Instead, gender functions as a given: it is taken to be a cross-cultural organising principle. Recently, some African scholars have begun to question the explanatory power of gender in African societies.1 This challenge came out of the desire to produce concepts grounded in African thought and everyday lived realities. These scholars hope that by focusing on an African episteme they will avoid any dependency on European theoretical paradigms and therefore eschew what Babalola Olabiyi Yai (1999) has called “dubious universals” and “intransitive discourses”. Some of the key questions that have been raised include: can gender, or indeed patriarchy, be applied to non- Euro-American cultures? Can we assume that social relations in all societies are organised around biological sex difference? Is the male body in African societies seen as normative and therefore a conduit for the exercise of power? Is the female body inherently subordinate to the male body? What are -

2016 Conference Program

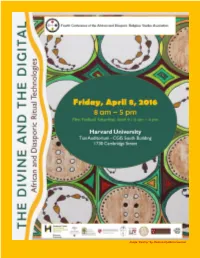

Image “Destiny” by Deanna Oyafemi Lowman MOYO ~ BIENVENIDOS ~ E KAABO ~ AKWABAA BYENVENI ~ BEM VINDOS ~ WELCOME Welcome to the fourth conference of the African and Diasporic Religious Studies Association! ADRSA was conceived during a forum of scholars and scholar- practitioners of African and Diasporic religions held at the Center for the Study of World Religions at Harvard Divinity School in October 2011 and the idea was solidified during the highly successful Sacred Healing and Wholeness in Africa and the Americas symposium held at Harvard in April 2012. Those present at the forum and the symposium agreed that, as with the other fields with which many of us are affiliated, the expansion of the discipline would be aided by the formation of an association that allows researchers to come together to forge relationships, share their work, and contribute to the growing body of scholarship on these rich traditions. We are proud to be the first US-based association dedicated exclusively to the study of African and Diasporic Religions and we look forward to continuing to build our network throughout the country and the world. Although there has been definite improvement, Indigenous Religions of all varieties are still sorely underrepresented in the academic realms of Religious and Theological Studies. As a scholar- practitioner of such a tradition, I am eager to see that change. As of 2005, there were at least 400 million people practicing Indigenous Religions worldwide, making them the 5th most commonly practiced class of religions. Taken alone, practitioners of African and African Diasporic religions comprise the 8th largest religious grouping in the world, with approximately 100 million practitioners, and the number continues to grow. -

Roger Atwood Searching for a Head in Nigeria

roger atwood Searching for a Head in Nigeria A century ago, a German colonialist went to Nigeria and found a bronze masterpiece. Then, it vanished. Nigerians have been asking themselves what happened to it ever since. Now they may have the answer. A place of “lofty trees . as beautiful as Paradise.” So the German adventurer Leo Frobenius described the sacred Olokun Grove in Ife in 1910. For months before I arrived in Nigeria, I wondered what the grove would look like. Now I was riding in a car to see the grove with a delegation of curators and archaeologists from the Ife museum. They had a certain ceremoni- ousness I had come to expect from educated Nigerians, and they were snappy dressers. While I sweated through my khakis and linen shirt, the women in the delegation wore flowered dresses and matching head- dresses, and they curtsied deeply and held out their hand coquettishly when we were introduced. The men called me “sir” and wore tailored robes with a matching cap, or immaculately ironed Western trousers and a pressed shirt and never a T-shirt or, God forbid, shorts. The Olokun Grove was on Irebami Street, near Line 3. It was a neighborhood of rut- ted streets and ramshackle houses, some with posters on their walls ad- vertising Nollywood movies or displaying President Goodluck Jonathan’s jowly face grafted onto the emerald bands of the national flag. In three weeks’ time, the people of Africa’s most populous country would vote in presidential elections. Not my concern. I was going to see a place as beautiful as Paradise.