Activating the Past

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sankofa Healing: a Womanist Analysis of the Retrieval and Transformation of African Ritual Dance

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Religious Studies Theses Department of Religious Studies 5-9-2015 Sankofa Healing: A Womanist Analysis of the Retrieval and Transformation of African Ritual Dance Karli Sherita Robinson-Myers Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/rs_theses Recommended Citation Robinson-Myers, Karli Sherita, "Sankofa Healing: A Womanist Analysis of the Retrieval and Transformation of African Ritual Dance." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2015. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/rs_theses/48 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Religious Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religious Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SANKOFA HEALING: A WOMANIST ANALYSIS OF THE RETRIEVAL AND TRANSFORMATION OF AFRICAN RITUAL DANCE by KARLI ROBINSON-MYERS Under the Direction of Monique Moultrie, Ph.D. ABSTRACT African American women who reach back into their (known or perceived) African ancestry, retrieve the rituals of that heritage (through African dance), and transform them to facilitate healing for their present communities, are engaging a process that I define as “Sankofa Healing.” Focusing on the work of Katherine Dunham as an exemplar, I will weave through her journey of retrieving and transforming African dance into ritual, and highlight what I found to be key components of this transformative process. Drawing upon Ronald Grimes’ ritual theory, and engaging the womanist body of thought, I will explore the impact that the process has on African-American women and their communities. -

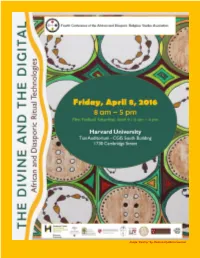

2016 Conference Program

Image “Destiny” by Deanna Oyafemi Lowman MOYO ~ BIENVENIDOS ~ E KAABO ~ AKWABAA BYENVENI ~ BEM VINDOS ~ WELCOME Welcome to the fourth conference of the African and Diasporic Religious Studies Association! ADRSA was conceived during a forum of scholars and scholar- practitioners of African and Diasporic religions held at the Center for the Study of World Religions at Harvard Divinity School in October 2011 and the idea was solidified during the highly successful Sacred Healing and Wholeness in Africa and the Americas symposium held at Harvard in April 2012. Those present at the forum and the symposium agreed that, as with the other fields with which many of us are affiliated, the expansion of the discipline would be aided by the formation of an association that allows researchers to come together to forge relationships, share their work, and contribute to the growing body of scholarship on these rich traditions. We are proud to be the first US-based association dedicated exclusively to the study of African and Diasporic Religions and we look forward to continuing to build our network throughout the country and the world. Although there has been definite improvement, Indigenous Religions of all varieties are still sorely underrepresented in the academic realms of Religious and Theological Studies. As a scholar- practitioner of such a tradition, I am eager to see that change. As of 2005, there were at least 400 million people practicing Indigenous Religions worldwide, making them the 5th most commonly practiced class of religions. Taken alone, practitioners of African and African Diasporic religions comprise the 8th largest religious grouping in the world, with approximately 100 million practitioners, and the number continues to grow. -

Suzanne Preston Blier Is Allen Whitehill Clowes Professor of Fine Arts and of African and African American Studies at Harvard University

Suzanne Preston Blier is Allen Whitehill Clowes Professor of Fine Arts and of African and African American Studies at Harvard University. Books include African Vodun: Art, Psychology, and Power (Charles Rufus Morey Prize winner), The Anatomy of Architecture: Ontology and Metaphor in Batammaliba Architectural Expression (Arnold Rubin Prize winner), African Royal Arts: the Majesty of Form (Choice Prize) and Art and Risk in Ancient Yoruba (Cambridge forthcoming). She is on the board of directors of the College Art Association and chairs the Steering Committee of WorldMap, an open source mapping website that she helped to create. Lazare Eloundou, architect and urban planner, joined UNESCO in 2003. He is Head of the Africa Unit of the UNESCO World Heritage Centre since March 2008. Born in Cameroon, he studied architecture at the School of Architecture in Grenoble (France) where he also specialized in earthen architecture construction and housing development. In 1995, he joined the International Centre for Earth Construction (CRATerre-ENSAG) as project specialist and researcher, where he conducted several housing projects in Africa. He was also from 2000 to 2003, one of the coordinators of the successful capacity building programme Africa 2009, for the improvement of the conservation of African cultural sites. In his capacity as Head of Africa Unit, he has been conducting missions and activities which have led to the inscription of new African sites on the UNESCO World Heritage List and to the implementation of numerous conservation projects in Mozambique, Ethiopia, Angola, Mali, and Uganda. He currently also coordinate UNESCO’s response for the protection of Mali’s World Heritage sites threatened by the armed conflict since April 2012. -

African Concepts of Energy and Their Manifestations Through Art

AFRICAN CONCEPTS OF ENERGY AND THEIR MANIFESTATIONS THROUGH ART A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Renée B. Waite August, 2016 Thesis written by Renée B. Waite B.A., Ohio University, 2012 M.A., Kent State University, 2016 Approved by ____________________________________________________ Fred Smith, Ph.D., Advisor ____________________________________________________ Michael Loderstedt, M.F.A., Interim Director, School of Art ____________________________________________________ John R. Crawford-Spinelli, D.Ed., Dean, College of the Arts TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES………………………………………….. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS …………………………………… vi CHAPTERS I. Introduction ………………………………………………… 1 II. Terms and Art ……………………………………………... 4 III. Myths of Origin …………………………………………. 11 IV. Social Structure …………………………………………. 20 V. Divination Arts …………………………………………... 30 VI. Women as Vessels of Energy …………………………… 42 VII. Conclusion ……………………………………….…...... 56 VIII. Images ………………………………………………… 60 IX. Bibliography …………………………………………….. 84 X. Further Reading ………………………………………….. 86 iii LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1: Porogun Quarter, Ijebu-Ode, Nigeria, 1992, Photograph by John Pemberton III http://africa.si.edu/exhibits/cosmos/models.html. ……………………………………… 60 Figure 2: Yoruba Ifa Divination Tapper (Iroke Ifa) Nigeria; Ivory. 12in, Baltimore Museum of Art http://www.artbma.org/. ……………………………………………… 61 Figure 3.; Yoruba Opon Ifa (Divination Tray), Nigerian; carved wood 3/4 x 12 7/8 x 16 in. Smith College Museum of Art, http://www.smith.edu/artmuseum/. ………………….. 62 Figure 4. Ifa Divination Vessel; Female Caryatid (Agere Ifa); Ivory, wood or coconut shell inlay. Nigeria, Guinea Coast The Metropolitan Museum of Art, http://www.metmuseum.org. ……………………… 63 Figure 5. Beaded Crown of a Yoruba King. Nigerian; L.15 (crown), L.15 (fringe) in. -

La Religiosidad En Gouverneurs De La Rosée De Jacques Roumain: Entre La Inmovilidad Y La Redención

La religiosidad en Gouverneurs de la rosée de Jacques Roumain: entre la inmovilidad y la redención The religiosity in Gouverneurs de la rosée by Jacques Roumain: between the immobility and the redemption Pablo Mauricio Hurtado Ruiz1 Resumen El presente trabajo analiza la religiosidad en la novela Gouverneurs de la rosée del escritor haitiano Jacques Roumain. Para ello, se establece que la religión que profesan los personajes corresponde a un sincretismo entre el catolicismo y el vuduísmo, en el que se manifiesta el conflicto entre la divinidad impuesta por el esclavismo y las divinidades heredadas de África. Se analiza la postura inmovilista que esta religiosidad significa para los habitantes de Fonds- Rouge, oponiéndose a la visión marxista del trabajo que presenta Manuel, el protagonista de la novela. Finalmente, pese a las críticas a la religión, el destino impuesto por las deidades del vudú, se cumple inexorablemente en contraposición al catolicismo que se cuestiona por ser una religión de blancos. Palabras clave: Gouverneurs de la rosée – religiosidad – catolicismo – vudú Abstract This paper analyzes the religiosity in the novel Gouverneurs de la rosée by the Haitian writer Jacques Roumain. For that purpose, it states that the religion professed by the character is a syncretism between the Catholicism and the voodoo, in which the conflict between the divinity imposed in the slavery period and the divinities inherit from Africa is manifested. This study analyzes the position of immobility that this religiosity means to the people of Fonds-Rouge, in opposition to the Marxist vision of the work introduced by Manuel, the principal character in the novel. -

Drawing Water, Drawing Breath: Vodun and the Bocio Tradition

Drawing Water, Drawing Breath: Vodun and the Bocio Tradition Odette Springer Commonly referred to as Voodoo, the sacred tradition of Vodun often conjures up the profane and demonized images of black magic, charms, and spells. Taken out of context, it infers hoaxes and devils. At best, it is a tradition often deemed inferior and unworthy of note by many scientific and academic institutions. Though Vodun is embedded in the ancient religious traditions of Africa it is not a coherent and cohesive totality and the word Vodun cannot be defined absolutely, or literalized. Vodun is a direct way of knowing, a cosmology far too complex to translate into a single, corresponding word. The first known written reference to Vodun appeared in a 1658 text called the Doctrina Christiana, where the term translates as “god,” “sacred,” or “priestly,” and is mentioned “in various forms about sixty times” (Labouret and Riviere qtd. in Blier 37). A general prejudice in the West against so-called primitive cultures contributes to the misunderstanding and bastardization of the word, yet a depth examination of Vodun reveals it to be a vibrant and essential tradition, one that has infiltrated modern psychology, religion and art. Not only is it infused in the blueprint of the industrialized West, its religious and philosophical ideas are acutely present and prevalent in our culture. Further, as a meditative art form associated with Vodun, the bocio tradition will also be discussed. Although scholars agree that Vodun is a living religion, many translations of the word have emerged over time, based on a different set of etymologies. -

Art in Ancient Ife, Birthplace of the Yoruba

Art in Ancient Ife, Birthplace of the Yoruba Suzanne Preston Blier rtists the world over shape knowledge and ancient works alongside diverse evidence on this center’s past material into works of unique historical and the time frame specific to when these sculptures were made. importance. The artists of ancient Ife, ances- In this way I bring art and history into direct engagement with tral home to the Yoruba and mythic birthplace each other, enriching both within this process. of gods and humans, clearly were interested in One of the most important events in ancient Ife history with creating works that could be read. Breaking respect to both the early arts and later era religious and political the symbolic code that lies behind the unique meanings of Ife’s traditions here was a devastating civil war pitting one group, the Aancient sculptures, however, has vexed scholars working on this supporters of Obatala (referencing today at once a god, a deity material for over a century. While much remains to be learned, pantheon, and the region’s autochthonous populations) against thanks to a better understanding of the larger corpus of ancient affiliates of Odudua (an opposing deity, religious pantheon, Ife arts and the history of this important southwestern Nigerian and newly arriving dynastic group). The Ikedu oral history text center, key aspects of this code can now be discerned. In this addressing Ife’s history (an annotated kings list transposed from article I explore how these arts both inform and are enriched by the early Ife dialect; Akinjogbin n.d.) indicates that it was during early Ife history and the leaders who shaped it.1 In addition to the reign of Ife’s 46th king—what appears to be two rulers prior core questions of art iconography and symbolism, I also address to the famous King Obalufon II (Ekenwa? Fig. -

Poisoned Relations: Medicine, Sorcery, and Poison Trials in the Contested Atlantic, 1680-1850

POISONED RELATIONS: MEDICINE, SORCERY, AND POISON TRIALS IN THE CONTESTED ATLANTIC, 1680-1850 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History By Chelsea L. Berry, B.A. Washington, DC March 25, 2019 Copyright 2019 by Chelsea L. Berry All Rights Reserved ii POISONED RELATIONS: MEDICINE, SORCERY, AND POISON TRIALS IN THE CONTESTED ATLANTIC, 1680-1850 Chelsea L. Berry, B.A. Thesis Advisor: Alison Games, Ph.D. ABSTRACT From 1680 to 1850, courts in the slave societies of the western Atlantic tried hundreds of free and enslaved people of African descent for poisoning others, often through sorcery. As events, poison accusations were active sites for the contestation of ideas about health, healing, and malevolent powers. Many of these cases centered on the activities of black medical practitioners. This thesis explores changes in ideas about poison through the wave of poison cases over this 170-year period and the many different people who made these changes and were bound up these cases. It analyzes over five hundred investigations and trials in Virginia, Bahia, Martinique, and the Dutch Guianas—each vastly different slave societies that varied widely in their conditions of enslaved labor, legal systems, and histories. It is these differences that make the shared patterns in the emergence, growth, and decline of poison cases, and of the relative importance of African medical practitioners within them, so intriguing. Across these four locations, there was a specific, temporally bounded, and widely shared relationship between poison, medicine, and sorcery in this period. -

Re-Mapping Hispaniola: Haiti in Dominican and Dominican American Literature

RE-MAPPING HISPANIOLA: HAITI IN DOMINICAN AND DOMINICAN AMERICAN LITERATURE By Megan Jeanette Myers Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Spanish August, 2016 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: William Luis, Ph.D. Ruth Hill, Ph.D. Lorraine López, Ph.D. Benigno Trigo, Ph.D. Copyright © 2016 by Megan Jeanette Myers All rights reserved ii Dedicated to my three Mars: My Dominican ahijadas, Marializ and Marisol, and my own sweet Marcela iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am incredibly thankful for the support of so many individuals with whom I have worked on this project. I am especially grateful for the support of my dissertation advisor, Professor William Luis. Thank you for your guidance and for pushing me to produce the best work possible. I chose to come to Vanderbilt in large part to work with you and you never disappointed me. Thank you for your advice during the academic job search and for giving me the opportunity to work with the Afro-Hispanic Review and the Latino and Latina Studies Program at Vanderbilt. I also want to thank the other members of my dissertation committee, Professor Ruth Hill, Professor Lorraine López, and Professor Benigno Trigo. Thank you for your thoughtful comments during my doctoral exams and for your time and support. I am incredibly thankful to Vanderbilt for all the opportunities it has provided me in terms of funding and academic support. A Summer Research Award from the Graduate School allowed me to conduct preliminary dissertation research in the Dominican Republic. -

Stewardship in West African Vodun: a Case Study of Ouidah, Benin

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2010 STEWARDSHIP IN WEST AFRICAN VODUN: A CASE STUDY OF OUIDAH, BENIN HAYDEN THOMAS JANSSEN The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation JANSSEN, HAYDEN THOMAS, "STEWARDSHIP IN WEST AFRICAN VODUN: A CASE STUDY OF OUIDAH, BENIN" (2010). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 915. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/915 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STEWARDSHIP IN WEST AFRICAN VODUN: A CASE STUDY OF OUIDAH, BENIN By Hayden Thomas Janssen B.A., French, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, 2003 Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In Geography The University of Montana Missoula, MT May 2010 Approved by: Perry Brown, Associate Provost for Graduate Education Graduate School Jeffrey Gritzner, Chairman Department of Geography Sarah Halvorson Department of Geography William Borrie College of Forestry and Conservation Tobin Shearer Department of History Janssen, Hayden T., M.A., May 2010 Geography Stewardship in West African Vodun: A Case Study of Ouidah, Benin Chairman: Jeffrey A. Gritzner Indigenous, animistic religions inherently convey a close relationship and stewardship for the environment. This stewardship is very apparent in the region of southern Benin, Africa. -

A Vodun Aesthetic in Selected Works of Simone Schwarz -Bart, Zora Neale Hurston, and Paule Marshall

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 2000 Slain in the Spirit: a Vodun Aesthetic in Selected Works of Simone Schwarz -Bart, Zora Neale Hurston, and Paule Marshall. Maria Thecla Smith Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Smith, Maria Thecla, "Slain in the Spirit: a Vodun Aesthetic in Selected Works of Simone Schwarz -Bart, Zora Neale Hurston, and Paule Marshall." (2000). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 7169. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/7169 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Palace Sculptures of Abomey Combines Color Photographs of the Bas-Reliefs with a Lively History of Dahomey, Complemented by Rare Historical Images

114 SUGGESTED READING Suggested Reading Assogba, Romain-Philippe. Le Musee d'Histoire Moss, Joyce, and George Wilson. Peoples de Ouidah: Decouverte de la COte des Esc/aves. of the Wo rld: Africans South of the Sahara. Ouidah, Benin: Editions Saint Michel, 1994. Detroit and London: Gale Research, 1991. Beckwith, Carol, and Angela Fisher. Pliya, Jean. Dahomey. Issy-les-Moulineaux, "The African Roots of Vo odoo." Na tional France: Classiques Africains, 1975. Geographic Magazine 88 (August 1995): 102-13. Ronen, Dov. Dahomey: Between Tradition and Blier, Suzanne Preston. African Vo dun: Art, Modernity. Ithaca, N.Y., and London: Cornell Psychology, and Power. Chicago: University of University Press, 1975. Chicago Press, 1995. Waterlot, E. G. Les bas-reliefs des Palais Royaux ___. "The Musee Historique in Abomey: d'Abomey. Paris: Institut d'Ethnologie, 1926. Art, Politics, and the Creation of an African Museum." In Arte in Africa 2. Florence: Centro In addition to the scholarly works listed above, di Studi di Storia delle Arte Africane, 1991. interested readers may consult Archibald ___. "King Glele of Danhome: Divination Dalzel's account of Dahomey in the late eigh Portraits of a Lion King and Man of Iron." teenth century, The History of Dahomy: African Arts 23, no. 4 (October 1990): 42-53, An Inland Kingdom ofAf rica (1793; reprint, London, Frank Cass and Co., 1967), and Sir 93-94· Richard Burton's A Mission to Gelele, King of "The Place Where Vo dun Was Born." Dahome (1864; reprint, London, Routledge & Na tural History Magazine 104 (October 1995): Kegan Paul, 1966); both offer historical 40-49· European perspectives on the Dahomey king Decalo, Samuel.