A Level History a African Kingdoms Ebook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Palace Sculptures of Abomey

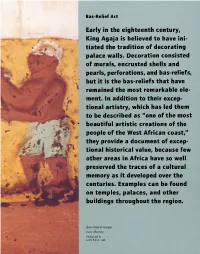

Bas-Relief Art Early in the eighteenth century, King Agaja is believed to have ini tiated the tradition of decorating palace walls. Decoration consisted of murals, encrusted shells and pearls, perfo rations, and bas-reliefs, , but it is the bas-reliefs that have remained the most remarkable ele ment. In addition to their excep tional artistry, which has led them to be described as "one of the most " beautiful artistic creations of the people of the West African coast, rr they provide a document of excep tional historical value, because few other areas in Africa have so well preserved the traces of a cultural · . memory as it developed over the centuries. Exa mples can be found on temples, palaces, and other buildings throughout the region. Bas-relief at temple near Abomey. Photograph by Leslie Railler, 1996. BAS-RELIEF ART 49 Commonly called noudide in Fon, from the root word meaning "to design" or "to portray," the bas-reliefs are three-dimensional, modeled- and painted earth pictograms. Early examples of the form, first in religious temples and then in the palaces, were more abstract than figurative. Gradually, figurative depictions became the prevalent style, illustrating the tales told by the kings' heralds and other Fon storytellers. Palace bas-reliefs were fashioned according to a long-standing tradition of The original earth architectural and sculptural renovation. used to make bas Ruling monarchs commissioned new palaces reliefs came from ter and artworks, as well as alterations of ear mite mounds such as lier ones, thereby glorifying the past while this one near Abomey. bringing its art and architecture up to date. -

'Neglected African Diaspora' of the Post-Communist Space

Pécs Journal of International and European Law - 2019/I-II. In Need of an Extended Research Approach: The Case of the ‘Neglected African Diaspora’ of the Post-Communist Space István Tarrósy1 Associate Professor This paper seeks to extend the academic discussion and research of the global African diaspora by drawing attention to Africans living in post-Communist spaces. So far, both literature and for- eign policies of countries of the former Eastern Bloc hardly ever made mention of this ‘neglected diaspora’. First, the paper underscores the relevance of specific research connected with African communities across Central and Eastern Europe, as well as present-day Russia. Second, it intro- duces the history, motivations, background and contemporary situation of the marginal but grow- ing African population in Hungary. It will show how finally the Hungarian government implements a pragmatic foreign policy (partly) on Africa and African development co-operation. In this effort, it considers Africans who either had obtained a university degree before 1989 at a Hungarian uni- versity, or came to the country during the democratic rule, as true bridges: they can foster newly defined relations. The place, role and potentials of these African migrants in the unique Hungar- ian migration environment will also be discussed. Increased illegal migration flows towards the European Union via the Serbian–Hungarian border region of the Schengen Zone in the first half of 2015 and the policies the Hungarian government introduced in the wake of this unprecedented push makes the discussion even more topical, in particular, as of early April 2019, a government “Africa Strategy” was also published. -

Africans: the HISTORY of a CONTINENT, Second Edition

P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 This page intentionally left blank ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 africans, second edition Inavast and all-embracing study of Africa, from the origins of mankind to the AIDS epidemic, John Iliffe refocuses its history on the peopling of an environmentally hostilecontinent.Africanshavebeenpioneersstrugglingagainstdiseaseandnature, and their social, economic, and political institutions have been designed to ensure their survival. In the context of medical progress and other twentieth-century innovations, however, the same institutions have bred the most rapid population growth the world has ever seen. The history of the continent is thus a single story binding living Africans to their earliest human ancestors. John Iliffe was Professor of African History at the University of Cambridge and is a Fellow of St. John’s College. He is the author of several books on Africa, including Amodern history of Tanganyika and The African poor: A history,which was awarded the Herskovits Prize of the African Studies Association of the United States. Both books were published by Cambridge University Press. i P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 african studies The African Studies Series,founded in 1968 in collaboration with the African Studies Centre of the University of Cambridge, is a prestigious series of monographs and general studies on Africa covering history, anthropology, economics, sociology, and political science. -

Legacies of Colonialism and Islam for Hausa Women: an Historical Analysis, 1804-1960

Legacies of Colonialism and Islam for Hausa Women: An Historical Analysis, 1804-1960 by Kari Bergstrom Michigan State University Winner of the Rita S. Gallin Award for the Best Graduate Student Paper in Women and International Development Working Paper #276 October 2002 Abstract This paper looks at the effects of Islamization and colonialism on women in Hausaland. Beginning with the jihad and subsequent Islamic government of ‘dan Fodio, I examine the changes impacting Hausa women in and outside of the Caliphate he established. Women inside of the Caliphate were increasingly pushed out of public life and relegated to the domestic space. Islamic law was widely established, and large-scale slave production became key to the economy of the Caliphate. In contrast, Hausa women outside of the Caliphate were better able to maintain historical positions of authority in political and religious realms. As the French and British colonized Hausaland, the partition they made corresponded roughly with those Hausas inside and outside of the Caliphate. The British colonized the Caliphate through a system of indirect rule, which reinforced many of the Caliphate’s ways of governance. The British did, however, abolish slavery and impose a new legal system, both of which had significant effects on Hausa women in Nigeria. The French colonized the northern Hausa kingdoms, which had resisted the Caliphate’s rule. Through patriarchal French colonial policies, Hausa women in Niger found they could no longer exercise the political and religious authority that they historically had held. The literature on Hausa women in Niger is considerably less well developed than it is for Hausa women in Nigeria. -

The Impact of the Second World War on the Decolonization of Africa

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU 17th Annual Africana Studies Student Research Africana Studies Student Research Conference Conference and Luncheon Feb 13th, 1:30 PM - 3:00 PM The Impact of the Second World War on the Decolonization of Africa Erin Myrice Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/africana_studies_conf Part of the African Languages and Societies Commons Myrice, Erin, "The Impact of the Second World War on the Decolonization of Africa" (2015). Africana Studies Student Research Conference. 2. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/africana_studies_conf/2015/004/2 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences and Events at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Africana Studies Student Research Conference by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. The Impact of the Second World War on the Decolonization of Africa Erin Myrice 2 “An African poet, Taban Lo Liyong, once said that Africans have three white men to thank for their political freedom and independence: Nietzsche, Hitler, and Marx.” 1 Marx raised awareness of oppressed peoples around the world, while also creating the idea of economic exploitation of living human beings. Nietzsche created the idea of a superman and a master race. Hitler attempted to implement Nietzsche’s ideas into Germany with an ultimate goal of reaching the whole world. Hitler’s attempted implementation of his version of a ‘master race’ led to one of the most bloody, horrific, and destructive wars the world has ever encountered. While this statement by Liyong was bold, it held truth. The Second World War was a catalyst for African political freedom and independence. -

An African Basketry of Heterogeneous Variables Kongo-Kikongo-Kisankasa

ISSN 2394-9694 International Journal of Novel Research in Humanity and Social Sciences Vol. 8, Issue 2, pp: (2-31), Month: March - April 2021, Available at: www.noveltyjournals.com An African Basketry of Heterogeneous Variables Kongo-Kikongo-Kisankasa Rojukurthi Sudhakar Rao (M.Phil Degree Student-Researcher, Centre for African Studies, University of Mumbai, Maharashtra Rajya, India) e-mail:[email protected] Abstract: In terms of scientific systems approach to the knowledge of human origins, human organizations, human histories, human kingdoms, human languages, human populations and above all the human genes, unquestionable scientific evidence with human dignity flabbergasted the European strong world of slave-masters and colonialist- policy-rulers. This deduces that the early Europeans knew nothing scientific about the mankind beforehand unleashing their one-up-man-ship over Africa and the Africans except that they were the white skinned flocks and so, not the kith and kin of the Africans in black skin living in what they called the „Dark Continent‟! Of course, in later times, the same masters and rulers committed to not repeating their colonialist racial geo-political injustices. The whites were domineering and weaponized to the hilt on their own mentality, for their own interests and by their own logic opposing the geopolitically distant African blacks inhabiting the natural resources enriched frontiers. Those „twists and twitches‟ in time-line led to the black‟s slavery and white‟s slave-trade with meddling Christian Adventist Missionaries, colonialists, religious conversionists, Anglican Universities‟ Missions , inter- sexual-births, the associative asomi , the dissociative asomi and the non-asomi divisions within African natives in concomitance. -

Christianity and the Formation of the Ideology of Power in Soyo in the 17Th Century

Studies in African Languages and Cultures, No 53, 2019 ISSN 2545-2134; e-ISSN 2657-4187 DOI: https://doi.org/10.32690/SALC53.6 Robert Piętek Siedlce University of Natural Sciences and Humanities Christianity and the formation of the ideology of power in Soyo in the 17th century Abstract The aim of the article is to present the role of the Christian elements in the formation of the ideology of power in Soyo in the mid of the 17th century. Thanks to its location, the province of Soyo played an important role in Kongo’s relations with Europe. Its location also meant that European influences in this province were stronger than in the rest of the Kingdom of Kongo. A permanent mission of the Capuchin order in Soyo was established as early as 1645. The province became virtually independent from Kongo in the 1640s. By that time, the political elite had formed an ideology of power largely based on the traditional elements of the Kongo culture. While it contained references to Christianity, the emphasis was put on the separateness and uniqueness of Soyo gained in victorious military conflicts with Kongo. The use of the Christian elements in rituals caused occasional conflicts between the secular authorities and the Capuchins. Keywords: Soyo, Kongo, Christianity, ideology of power 1. Introduction During the early modern period, Kongo constituted a fascinating example of an African state whose ruler and a considerable amount of political elites were in- terested in maintaining close relations with Europe, from the very first contacts established with the Portuguese toward the end of the 15th century. -

Black Rhetoric: the Art of Thinking Being

BLACK RHETORIC: THE ART OF THINKING BEING by APRIL LEIGH KINKEAD Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON May 2013 Copyright © by April Leigh Kinkead 2013 All Rights Reserved ii Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without the guidance, advice, and support of others. I would like to thank my advisor, Cedrick May, for his taking on the task of directing my dissertation. His knowledge, advice, and encouragement helped to keep me on track and made my completing this project possible. I am grateful to Penelope Ingram for her willingness to join this project late in its development. Her insights and advice were as encouraging as they were beneficial to my project’s aims. I am indebted to Kevin Gustafson, whose careful reading and revisions gave my writing skills the boost they needed. I am a better writer today thanks to his teachings. I also wish to extend my gratitude to my school colleagues who encouraged me along the way and made this journey an enjoyable experience. I also wish to thank the late Emory Estes, who inspired me to pursue graduate studies. I am equally grateful to Luanne Frank for introducing me to Martin Heidegger’s theories early in my graduate career. This dissertation would not have come into being without that introduction or her guiding my journey through Heidegger’s theories. I must also thank my family and friends who have stood by my side throughout this long journey. -

« Palais Royaux D'abomey » (Benin)

« PALAIS ROYAUX D’ABOMEY » (BENIN) RAPPORT MISSION CONJOINTE DE SUIVI REACTIF CENTRE DU PATRIMOINE MONDIAL/ICOMOS/ICCROM DU 18 AU 22 AVRIL 2016 Sommaire REMERCIEMENTS .............................................................................................................................................. 4 Résumé et recommandations .......................................................................................................................... 5 I. ANTECEDENTS DE LA MISSION .................................................................................................................. 9 1.1. Historique ...................................................................................................................................... 9 1.2. Critère d’inscription sur la Liste du patrimoine mondial .......................................................... 10 1.3. Menaces pesant sur l’authenticité, soulevées dans le rapport d’évaluation de l’ICOMOS au moment de l’inscription .............................................................................................................. 12 1.4. Retrait du bien de la Liste du patrimoine mondial en péril ....................................................... 13 1.5. Examen de l’état de conservation par le Comité du patrimoine mondial ................................ 14 1.6. Justification de la mission ........................................................................................................... 15 1.7. Composition de la mission ......................................................................................................... -

The Skeletal Biology, Archaeology and History of the New York African Burial Ground: a Synthesis of Volumes 1, 2, and 3

THE NEW YORK AFRICAN BURIAL GROUND U.S. General Services Administration VOL. 4 The Skeletal Biology, Archaeology and History of the New York African Burial Ground: Burial African York New History and of the Archaeology Biology, Skeletal The THE NEW YORK AFRICAN BURIAL GROUND: Unearthing the African Presence in Colonial New York Volume 4 A Synthesis of Volumes 1, 2, and 3 Volumes of A Synthesis Prepared by Statistical Research, Inc Research, Statistical by Prepared . The Skeletal Biology, Archaeology and History of the New York African Burial Ground: A Synthesis of Volumes 1, 2, and 3 Prepared by Statistical Research, Inc. ISBN: 0-88258-258-5 9 780882 582580 HOWARD UNIVERSITY HUABG-V4-Synthesis-0510.indd 1 5/27/10 11:17 AM THE NEW YORK AFRICAN BURIAL GROUND: Unearthing the African Presence in Colonial New York Volume 4 The Skeletal Biology, Archaeology, and History of the New York African Burial Ground: A Synthesis of Volumes 1, 2, and 3 Prepared by Statistical Research, Inc. HOWARD UNIVERSITY PRESS WASHINGTON, D.C. 2009 Published in association with the United States General Services Administration The content of this report is derived primarily from Volumes 1, 2, and 3 of the series, The New York African Burial Ground: Unearthing the African Presence in Colonial New York. Application has been filed for Library of Congress registration. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. General Services Administration or Howard University. Published by Howard University Press 2225 Georgia Avenue NW, Suite 720 Washington, D.C. -

The Rise of Islamic Resurgence in Somalia

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/256191703 The Rise of Islamic Resurgence in Somalia Chapter · January 2013 DOI: 10.13140/2.1.4025.1843 CITATIONS READS 0 665 1 author: Valeria Saggiomo Università degli Studi di Napoli L'Orientale 11 PUBLICATIONS 9 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: decentralized cooperation and local governance in Senegal and Burkina Faso (2014) View project All content following this page was uploaded by Valeria Saggiomo on 08 March 2017. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. NOVA COLLECTANEA AFRICANA COLLANA DEL CENTRO DI STUDI AFRICANI IN SARDEGNA 2 Editor in Chief Bianca Maria Carcangiu Università degli Studi di Cagliari Editorial Board Catherine Coquer-Vidrovitch Université Paris Diderot — Paris 7, France Federico Cresti Università degli Studi di Catania, Italy Joan Haig University of Edinburgh, UK Habib Kazdaghli Université de Tunis-Manouba, Tunisia Nicola Melis Università di Cagliari, Italy Jean-Louis Triaud CEMAf — Université de Provence, France For information and contributions: http: // www.csas.it/ | [email protected] http: //affrica.org/ | [email protected] Work published with the contribution of: Provincia di Cagliari — Provincia de Casteddu, Ufficio di Presidenza Politics and Minorities in Africa Edited by Marisa Fois Alessandro Pes Contributors Gado Alzouma, Richard Goodridge, Henry Gyang Mang Mohamed Haji Ingiriis, Akin Iwilade, Giuseppe Maimone Alessia Melcangi, Sabelo J. Ndlovu--Gatsheni, Iwebunor Okwechime Yoon Jung Park, Mauro Piras, Valeria Saggiomo Elisabetta Spano, Bianca Maria Carcangiu Copyright © MMXIII ARACNE editrice S.r.l. www.aracneeditrice.it [email protected] via Raffaele Garofalo, 133/A–B 00173 Roma (06) 93781065 isbn 978–88–548–5700–1 No part of this book may be reproduced by print, photoprint, microfilm, microfiche, or any other means, without publisher’s authorization. -

Chapter Two: the Global Context: Asia, Europe, and Africa in the Early Modern Era

Chapter Two: The Global Context: Asia, Europe, and Africa in the Early Modern Era Contents 2.1 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................. 30 2.1.1 Learning Outcomes ....................................................................................... 30 2.2 EUROPE IN THE AGE OF DISCOVERY: PORTUGAL AND SPAIN ........................... 31 2.2.1 Portugal Initiates the Age of Discovery ............................................................. 31 2.2.2 The Spanish in the Age of Discovery ................................................................ 33 2.2.3 Before You Move On... ................................................................................... 35 Key Concepts ....................................................................................................35 Test Yourself ...................................................................................................... 36 2.3 ASIA IN THE AGE OF DISCOVERY: CHINESE EXPANSION DURING THE MING DYNASTY 37 2.3.1 Before You Move On... ................................................................................... 40 Key Concepts ................................................................................................... 40 Test Yourself .................................................................................................... 41 2.4 EUROPE IN THE AGE OF DISCOVERY: ENGLAND AND FRANCE ........................ 41 2.4.1 England and France at War ..........................................................................