Armenian Philology in the Modern Era

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Christians and Jews in Muslim Societies

Arabic and its Alternatives Christians and Jews in Muslim Societies Editorial Board Phillip Ackerman-Lieberman (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, USA) Bernard Heyberger (EHESS, Paris, France) VOLUME 5 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/cjms Arabic and its Alternatives Religious Minorities and Their Languages in the Emerging Nation States of the Middle East (1920–1950) Edited by Heleen Murre-van den Berg Karène Sanchez Summerer Tijmen C. Baarda LEIDEN | BOSTON Cover illustration: Assyrian School of Mosul, 1920s–1930s; courtesy Dr. Robin Beth Shamuel, Iraq. This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Murre-van den Berg, H. L. (Hendrika Lena), 1964– illustrator. | Sanchez-Summerer, Karene, editor. | Baarda, Tijmen C., editor. Title: Arabic and its alternatives : religious minorities and their languages in the emerging nation states of the Middle East (1920–1950) / edited by Heleen Murre-van den Berg, Karène Sanchez, Tijmen C. Baarda. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, 2020. | Series: Christians and Jews in Muslim societies, 2212–5523 ; vol. -

Vincentian Missions in the Islamic World

Vincentian Heritage Journal Volume 5 Issue 1 Article 1 Spring 1984 Vincentian Missions in the Islamic World Charles A. Frazee Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vhj Recommended Citation Frazee, Charles A. (1984) "Vincentian Missions in the Islamic World," Vincentian Heritage Journal: Vol. 5 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vhj/vol5/iss1/1 This Articles is brought to you for free and open access by the Vincentian Journals and Publications at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vincentian Heritage Journal by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Vincentian Missions in the Islamic World Charles A. Frazee When Saint Vincent de Paul organized the Congrega- tion of the Mission and the Daughters of Charity, one of his aims was to provide a group of men and women who would work in foreign lands on behalf of the Church. He held firm opinions on the need for such a mission since at the very heart of Christ's message was the charge to go to all nations preaching the Gospel. St. Vincent believed that the life of a missionary would win more converts than theological arguments. Hence his instructions to his dis- ciples were always meant to encourage them to lead lives of charity and concern for the poor. This article will describe the extension of Vincent's work into the Islamic world. Specifically, it will touch on the Vincentian experience in North Africa, the Ottoman Empire (including Turkey, the Near East, and Balkan countries), and Persia (Iran). -

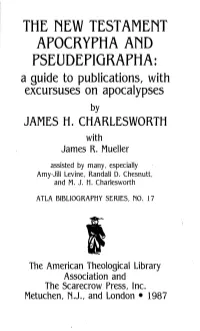

THE NEW TESTAMENT APOCRYPHA and PSEUDEPIQRAPHA: a Guide to Publications, with Excursuses on Apocalypses by JAMES H

THE NEW TESTAMENT APOCRYPHA AND PSEUDEPIQRAPHA: a guide to publications, with excursuses on apocalypses by JAMES H. CHARLESWORTH with James R. Mueller assisted by many, especially Amy-Jill Levine, Randall D. Chesnutt, and M. J. H. Charlesworth ATLA BIBLIOGRAPHY SERIES, MO. 17 The American Theological Library Association and The Scarecrow Press, Inc. Metuchen, N.J., and London • 1987 CONTENTS Editor's Foreword xiii Preface xv I. INTRODUCTION 1 A Report on Research 1 Description 6 Excluded Documents 6 1) Apostolic Fathers 6 2) The Nag Hammadi Codices 7 3) The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha 7 4) Early Syriac Writings 8 5) Earliest Versions of the New Testament 8 6) Fakes 9 7) Possible Candidates 10 Introductions 11 Purpose 12 Notes 13 II. THE APOCALYPSE OF JOHN—ITS THEOLOGY AND IMPACT ON SUBSEQUENT APOCALYPSES Introduction . 19 The Apocalypse and Its Theology . 19 1) Historical Methodology 19 2) Other Apocalypses 20 3) A Unity 24 4) Martyrdom 25 5) Assurance and Exhortation 27 6) The Way and Invitation 28 7) Transference and Redefinition -. 28 8) Summary 30 The Apocalypse and Its Impact on Subsequent Apocalypses 30 1) Problems 30 2) Criteria 31 3) Excluded Writings 32 4) Included Writings 32 5) Documents , 32 a) Jewish Apocalypses Significantly Expanded by Christians 32 b) Gnostic Apocalypses 33 c) Early Christian Apocryphal Apocalypses 34 d) Early Medieval Christian Apocryphal Apocalypses 36 6) Summary 39 Conclusion 39 1) Significance 39 2) The Continuum 40 3) The Influence 41 Notes 42 III. THE CONTINUUM OF JEWISH AND CHRISTIAN APOCALYPSES: TEXTS AND ENGLISH TRANSLATIONS Description of an Apocalypse 53 Excluded "Apocalypses" 54 A List of Apocalypses 55 1) Classical Jewish Apocalypses and Related Documents (c. -

16, We Begin the Publication of His Diary, So As to Possess in One Single Collection All His Writings Relative to the Congregation and His Ascetic and Mystical Life

St. EUGENE de MAZENOD DIARY (1791 - 1821) Translated by Michael Hughes, O.M.I. Oblate General Archives Via Aurelia, 290 Rome, 1999 Printed by MARIAN PRESS LTD. BATTLEFORD, SASKATCHEWAN, CANADA Table of Contents pp. Introduction ...................................................................................... 7 A Diary of the Exile in Italy (1721-1802).............................. 11 Introduction.................................................................................. 11 T e x t................................................................................................ 19 B Diary of a Stay in Paris (1805) ............................................ 103 Introduction.................................................................................. 103 T e x t................................................................................................ 109 C Diary of the Aix Christian Youth Congregation (1813-1821) ............................................................................... 121 Introduction.................................................................................. 121 T e x t................................................................................................ 233 D Diary of the Mission of Marignane (November 17 - December 1 5 ,1 8 1 6 )................................... 209 Introduction.................................................................................. 209 T ex t................................................................................................ 213 Illustrations -

An Historical Evaluation of the Covenants of the Prophet Muḥammad and 'Alī Ibn Abī Ṭālib in the Matenadaran "2279

religions Article An Historical Evaluation of the Covenants of the Prophet † Muh. ammad and ‘Alı¯ ibn Abı¯ T. alib¯ in the Matenadaran Gayane Mkrtumyan Faculty of Oriental Studies, Yerevan State University, Yerevan 0025, Armenia; [email protected] † I would like to thank Prof. Ibrahim Zein and Mr. Ahmed El-Wakil for their kind assistance in finalizing this article. Abstract: This article analyzes the manuscripts in the Matenadaran in Yerevan, Armenia that are ascribed to the Prophet Muh. ammad and ‘Al¯ı ibn Ab¯ı T. alib¯ and their translations into Farsi and Armenian. These important manuscripts have until now been neglected by scholars, and so we will here provide a general overview of them and how they were received by the Armenian Apostolic Church. I herein demonstrate how these documents were recognized by Muslim authorities, shedding light on how Muslim rulers managed the affairs of their Christian subjects. These documents, it would seem, also influenced the decrees of Muslim rulers to the Armenian Apostolic Church. Keywords: covenant; Prophet Muhammad; Ali ibn Abi Talib; Matenadaran; Armenia; Armenian Apostolic Church 1. Introduction Citation: Mkrtumyan, Gayane. 2021. The Matenadaran, which is officially known as the Mesrop Mashtots Institute of An Historical Evaluation of the Ancient Manuscripts, is the world’s largest repository of Armenian manuscripts. Situated Covenants of the Prophet in Yerevan, the capital of Armenia, the Matenadaran was established in 1959 CE during Muhammad and ‘Al¯ı ibn Ab¯ı Talib¯ in . the Soviet era, having incorporated the collection of manuscripts that was held by the the Matenadaran . Religions 12: 138. Armenian Church in Etchmiadzin. -

Eugène Boré and the Vincentian Missions in the Near East

Vincentian Heritage Journal Volume 5 Issue 1 Article 2 Spring 1984 Eugène Boré and the Vincentian Missions in the Near East Stafford Poole C.M. Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vhj Recommended Citation Poole, Stafford C.M. (1984) "Eugène Boré and the Vincentian Missions in the Near East," Vincentian Heritage Journal: Vol. 5 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vhj/vol5/iss1/2 This Articles is brought to you for free and open access by the Vincentian Journals and Publications at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vincentian Heritage Journal by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 59 Eugene Bore" and the Vincentian Missions in the Near East* Stafford Poole, G.M. Western Europeans have always been fascinated by the East but rarely more so than in the nineteenth century. A combination of factors quickened this interest and inau- gurated decades of exploration, investigation, exploitation, and converson. Archeology, linguistics, renewed interest in ancient history, biblical studies, economic expansion, political domination, exoticism, and arm-chair adventure - all were factors in this new pull to the east. Explorers and travelers, often subsidized by learned societies, visited these strange lands and published accounts that were eagerly devoured in the drawing-rooms of France and England. In politics and foreign policy the "Eastern Ques- tion" came to play a major and sometimes dominant role. In that same century the Roman Catholic Church, which in the aftermath of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic wars was undergoing a long period of recon- struction, centralization, and expansion, caught the fever and extended its missionary activities to the orient in a special way. -

1 Peter “Be Holy”

1 Peter “Be Holy” Bible Knowledge Commentary States: “First Peter was written to Christians who were experiencing various forms of persecution, men and women whose stand for Jesus Christ made them aliens and strangers in the midst of a pagan society. Peter exhorted these Christians to steadfast endurance and exemplary behavior. The warmth of his expressions combined with his practical instructions make this epistle a unique source of encouragement for all believers who live in conflict with their culture. I. Setting 1 Peter is the 19th book of the New Testament and 16th among the Epistles or letters. They are the primary doctrinal portions of the New Testament. It is not that the Gospels and Acts do not contain doctrine, but that the purpose of the Epistles is to explain to churches and individuals how to apply the teachings of Jesus. Jesus’ earthly life models ministry. In every area of ministry, we must apply the example of Christ. He was filled with the Spirit, sought to honor God, put a high value on people, and lowered Himself as the servant of all. Once He ascended to heaven, He poured His Spirit out on believers and the New Testament church was formed. Acts focuses on the birth, establishment, and furtherance of the work of God in the world, through the church. The Epistles are written to the church, further explaining doctrine. A. 1Peter is part of a section among the Epistles commonly known as “The Hebrew Christian Epistles” and includes Hebrews, James, 1 and 2 Peter, 1st, 2nd and 3rd John and Jude. -

Christians and Jews in the Ottoman Empire: the Abridged Edition

EXCERPTED FROM Christians and Jews in the Ottoman Empire: The Abridged Edition edited by Benjamin Braude Copyright © 2014 ISBNs: 978-1-58826-889-1 hc 978-1-58826-865-5 pb 1800 30th Street, Suite 314 Boulder, CO 80301 USA telephone 303.444.6684 fax 303.444.0824 This excerpt was downloaded from the Lynne Rienner Publishers website www.rienner.com Contents Preface vii List of Abbreviations ix Note on Transliteration x 1 Introduction 1 Benjamin Braude 2 Transformation of Zimmi into Askerî 51 İ. Metin Kunt 3 Foundation Myths of the Millet System 65 Benjamin Braude 4 The Rise of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople 87 Kevork B. Bardakjian 5 Ottoman Policy Toward the Jews and Jewish Attitudes Toward the Ottomans During the Fifteenth Century 99 Joseph R. Hacker 6 The Greek Millet in the Ottoman Empire 109 Richard Clogg 7 The Dual Role of the Armenian Amira Class Within the Ottoman Government and the Armenian Millet 133 Hagop Barsoumian 8 Foreign Merchants and the Minorities in Istanbul During the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries 147 Robert Mantran 9 The Transformation of the Economic Position of the Millets in the Nineteenth Century 159 Charles Issawi v vi Contents 10 The Millets as Agents of Change in the Nineteenth-Century Ottoman Empire 187 Roderic H. Davison 11 The Acid Test of Ottomanism: The Acceptance of Non-Muslims in the Late Ottoman Bureaucracy 209 Carter V. Findley 12 Communal Conflict in Ottoman Syria During the Reform Era: The Role of Political and Economic Factors 241 Moshe Ma‘oz 13 Communal Conflict in Nineteenth-Century Lebanon 257 Samir Khalaf 14 Unionist Relations with the Greek, Armenian, and Jewish Communities of the Ottoman Empire, 1908 –1914 287 Feroz Ahmad 15 The Political Situation of the Copts, 1798 –1923 325 Doris Behrens-Abouseif Selected Bibliography 347 About the Contributors 355 Index 357 About the Book 374 1 Introduction Benjamin Braude Thirty years ago the first edition of this book appeared. -

Time After Pentecost

This is a digital copy of a book that was preserved for generations on library shelves before it was carefully scanned by Google as part of a project to make the world’s books discoverable online. It has survived long enough for the copyright to expire and the book to enter the public domain. A public domain book is one that was never subject to copyright or whose legal copyright term has expired. Whether a book is in the public domain may vary country to country. Public domain books are our gateways to the past, representing a wealth of history, culture and knowledge that’s often difficult to discover. Marks, notations and other marginalia present in the original volume will appear in this file - a reminder of this book’s long journey from the publisher to a library and finally to you. Usage guidelines Google is proud to partner with libraries to digitize public domain materials and make them widely accessible. Public domain books belong to the public and we are merely their custodians. Nevertheless, this work is expensive, so in order to keep providing this resource, we have taken steps to prevent abuse by commercial parties, including placing technical restrictions on automated querying. We also ask that you: + Make non-commercial use of the files We designed Google Book Search for use by individuals, and we request that you use these files for personal, non-commercial purposes. + Refrain from automated querying Do not send automated queries of any sort to Google’s system: If you are conducting research on machine translation, optical character recognition or other areas where access to a large amount of text is helpful, please contact us. -

GBNT-500 Acts of the Apostles Cmt 1566614590902

GBNT 500 The Acts of the Apostles 7th Revision, October 2011 Midwest Seminary of Bible Theology Acts of the Apostles GBNT 500 Midwest Seminary of Bible Theology 1 This material is not to be copied for any purpose without written permission from American Mission Teams © Copyright by American Mission Teams, Inc., All rights reserved, printed in the United States of America GBNT 500 The Acts of the Apostles 7th Revision, October 2011 Midwest Seminary of Bible Theology ARE YOU BORN AGAIN? Knowing in your heart that you are born-again and followed by a statement of faith are the two prerequisites to studying and getting the most out of your MSBT materials. We at MSBT have developed this material to educate each Believer in the principles of God. Our goal is to provide each Believer with an avenue to enrich their personal lives and bring them closer to God. Is Jesus your Lord and Savior? If you have not accepted Him as such, you must be aware of what Romans 3:23 tells you. 23 For all have sinned, and come short of the glory of God: How do you go about it? You must believe that Jesus is the Son of God. I John 5:13 gives an example in which to base your faith. 13 These things have I written unto you that believe on the name of the Son of God; that ye may know that ye have eternal life, and that ye may believe on the name of the Son of God. What if you are just not sure? Romans 10:9-10 gives you the Scriptural mandate for becoming born-again. -

Minorities in the South Caucasus: New Visibility Amid Old Frustrations

DIRECTORATE-GENERAL FOR EXTERNAL POLICIES POLICY DEPARTMENT IN-DEPTH ANALYSIS Minorities in the South Caucasus: New visibility amid old frustrations Author: Fernando GARCÉS DE LOS FAYOS Abstract One of the most multi-ethnic regions on Europe’s periphery, the South Caucasus’s bumpy path to democracy has often been accompanied by ethnic conflict, stoked by nationalism. Since acquiring independence from the Soviet Union, secessionist movements have grown among local minorities in the areas surrounding the countries’ new, sovereign borders. The lack of state mechanisms to channel such sentiments has led to violent ethnic clashes with long-lasting consequences. Today still, a lack of experience in conflict resolution and power- sharing between dominant and minority communities hinders the development of common ground and democratic co-existence. Mechanisms which promote parliamentary representation, law-making and the oversight of minority rights are still largely absent. Although reforms in the South Caucasus have pushed for new laws to create greater accountability, instruments promoting inclusive dialogue with the minorities require further development. For the minorities of the South Caucasus, the most pressing issues are a lack of respect and the protection of their rights. For the sake of state-building and democratic development of the region, inclusive policies must be implemented with respect to ethnic minorities, through their political participation, including them in the higher levels of decision-making. DG EXPO/B/PolDep/Note/2014_104 June 2014 ST/1030125 PE 522.341 EN Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies This paper is an initiative of the Policy Department, DG EXPO. AUTHORS: Fernando GARCÉS DE LOS FAYOS with contributions from Nata KERESELIDZE, intern (based on a previous paper by Anastasia BASKINA, intern) Directorate-General for External Policies of the Union Policy Department SQM 03 Y 71 rue Wiertz 60 B-1047 Brussels Editorial Assistant: Györgyi MÁCSAI CONTACT: Feedback of all kinds is welcome. -

Eugène Boré and the Bulgarian Catholic Movement

Vincentian Heritage Journal Volume 16 Issue 2 Article 5 Fall 1995 Eugène Boré and the Bulgarian Catholic Movement Stafford Poole C.M. Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vhj Recommended Citation Poole, Stafford C.M. (1995) "Eugène Boré and the Bulgarian Catholic Movement," Vincentian Heritage Journal: Vol. 16 : Iss. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vhj/vol16/iss2/5 This Articles is brought to you for free and open access by the Vincentian Journals and Publications at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vincentian Heritage Journal by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 193 Eugene Bore' and the Bulgarian Catholic Movement BY STAFFORD POOLE, C.M.1 It has long been accepted among historians that nationalism was the dominant force in nineteenth-century Europe. The development of national consciousness among peoples, however, was varied and com- plex. At times it manifested itself in an attempt to achieve an ethnic identity and independence of foreign rule. At other times it involved a process of unification into a nation-state or an empire. In some countries it took on the characteristics of imperialism. A sense of national identity has often been linked with religious values, as in Ireland and Poland. For centuries Bulgaria, like most of the Balkans, was under the political and military rule of the Islamic Ottoman Empire, while the Bulgarian Church was subject to the Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Constantinople. As in some other countries nationalism began with a revival of the Bulgarian language and the spread of education.