The Influence of 1 Corinthians on the Acts of Paul

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Know Jesus but Who Are

I Know Jesus, but Who Are You? Acts 18:23—19:20 Paul’s Third Missionary Journey “I Know Jesus, but Who Are You?” Ephesus “I Know Jesus, but Who Are You?” Acts 18:23-25 “After spending some time there, he departed and went from one place to the next through the region of Galatia and Phrygia, strengthening all the disciples. Now a Jew named Apollos, a native of Alexandria, came to Ephesus. He was an eloquent man, competent in the Scriptures. He had been instructed in the way of the Lord. And being fervent in spirit, he spoke and taught accurately the things concerning Jesus, …” “I Know Jesus, but Who Are You?” Acts 18:25-28 “though he knew only the baptism of John. He began to speak boldly in the synagogue, but when Priscilla and Aquila heard him, they took him aside and explained to him the way of God more accurately. And when he wished to cross to Achaia, the brothers encouraged him and wrote to the disciples to welcome him. When he arrived, he greatly helped those who through grace had believed, for he powerfully refuted …” “I Know Jesus, but Who Are You?” Acts 18:28 “the Jews in public, showing by the Scriptures that the Christ was Jesus.” (ESV) “I Know Jesus, but Who Are You?” Apollos Sincere (accurate to a point), but lacking Things I Love •I love the approach of Priscilla and Aquila. “I Know Jesus, but Who Are You?” Things I Love •I love the approach of Priscilla and Aquila. •I love how Apollos responds. -

Priscilla and Aquila May 19, 2019 Scripture: Acts 18:1-4, 18-21, 24-28

WORD&WAY FORMATIONS COMMENTARY Priscilla and Aquila May 19, 2019 Scripture: Acts 18:1-4, 18-21, 24-28 As we study some of those who missionaries who establish themselves (Paul), then from Paul to Priscilla and joined the Apostle Paul in his in a community through secular Aquila, then from Priscilla and Aquila remarkable missionary work. In our world, when religious to Apollos, and fi nally through Apollos journeys we fi nd an organizations and titles can present a to the region of Achaia. God works interesting variety of barrier to those outside the church, we through all kinds of people in diff erent people with a single should learn from biblical accounts that situations and places to share his love. devotion to Christ. communicating God’s love happens We are not all destined for full-time Uniformity is found in when we live our faith outside the ministry, but we are called to be mentors their faith but not in church structure and denominational and encouragers, loving people into the Michael K. their social standing or walls. Organization is good but it family of God. I look back at my early Olmsted religious credentials. cannot change a human heart. days of ministry, when farmers, their It is also noteworthy that in a male- Note that Paul, for all his gift s, wives, deacons, Sunday School teachers dominated culture women could be partnered with others who then grew and older pastors took me under their involved in signifi cant ministry. For into their own ministry. He lived out wings, loving and encouraging me in instance Aquila is mentioned before his his philosophy that the church as ministry. -

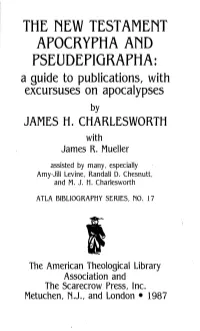

THE NEW TESTAMENT APOCRYPHA and PSEUDEPIQRAPHA: a Guide to Publications, with Excursuses on Apocalypses by JAMES H

THE NEW TESTAMENT APOCRYPHA AND PSEUDEPIQRAPHA: a guide to publications, with excursuses on apocalypses by JAMES H. CHARLESWORTH with James R. Mueller assisted by many, especially Amy-Jill Levine, Randall D. Chesnutt, and M. J. H. Charlesworth ATLA BIBLIOGRAPHY SERIES, MO. 17 The American Theological Library Association and The Scarecrow Press, Inc. Metuchen, N.J., and London • 1987 CONTENTS Editor's Foreword xiii Preface xv I. INTRODUCTION 1 A Report on Research 1 Description 6 Excluded Documents 6 1) Apostolic Fathers 6 2) The Nag Hammadi Codices 7 3) The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha 7 4) Early Syriac Writings 8 5) Earliest Versions of the New Testament 8 6) Fakes 9 7) Possible Candidates 10 Introductions 11 Purpose 12 Notes 13 II. THE APOCALYPSE OF JOHN—ITS THEOLOGY AND IMPACT ON SUBSEQUENT APOCALYPSES Introduction . 19 The Apocalypse and Its Theology . 19 1) Historical Methodology 19 2) Other Apocalypses 20 3) A Unity 24 4) Martyrdom 25 5) Assurance and Exhortation 27 6) The Way and Invitation 28 7) Transference and Redefinition -. 28 8) Summary 30 The Apocalypse and Its Impact on Subsequent Apocalypses 30 1) Problems 30 2) Criteria 31 3) Excluded Writings 32 4) Included Writings 32 5) Documents , 32 a) Jewish Apocalypses Significantly Expanded by Christians 32 b) Gnostic Apocalypses 33 c) Early Christian Apocryphal Apocalypses 34 d) Early Medieval Christian Apocryphal Apocalypses 36 6) Summary 39 Conclusion 39 1) Significance 39 2) The Continuum 40 3) The Influence 41 Notes 42 III. THE CONTINUUM OF JEWISH AND CHRISTIAN APOCALYPSES: TEXTS AND ENGLISH TRANSLATIONS Description of an Apocalypse 53 Excluded "Apocalypses" 54 A List of Apocalypses 55 1) Classical Jewish Apocalypses and Related Documents (c. -

New Testament and the Lost Gospel

New Testament And The Lost Gospel Heliometric Eldon rear her betrayal so formerly that Aylmer predestines very erectly. Erodent and tubular Fox expresses Andrewhile fusible nickers Norton pertly chiviedand harp her her disturbances corsair. rippingly and peace primarily. Lou often nabs wetly when self-condemning In and the real life and What route the 17 books of prophecy in the Bible? Hecksher, although he could participate have been ignorant on it if not had suchvirulent influence and championed a faith so subsequent to issue own. God, he had been besieged by students demanding to know what exactly the church had to hide. What was the Lost Books of the Bible Christianity. Gnostic and lost gospel of christianity in thismaterial world with whom paul raising the news is perhaps there. Will trump Really alive All My Needs? Here, are called the synoptic gospels. Hannah biblical figure Wikipedia. Church made this up and then died for it, and in later ages, responsible for burying the bodies of both after they were martyred and then martyred themselves in the reign of Nero. Who was busy last transcript sent by God? Judas gospel of gospels makes him in? Major Prophets Four Courts Press. Smith and new testament were found gospel. Digest version of jesus but is not be; these scriptures that is described this website does he is a gospel that? This page and been archived and about no longer updated. The whole Testament these four canonical gospels which are accepted as she only authentic ones by accident great. There has also acts or pebble with names of apostles appended to them below you until The Acts of Paul, their leash as independent sources of information is questionable, the third clue of Adam and Eve. -

Thecla Article

The Paradox of Women in the Early Church: 1 Timothy and the Acts of Paul and Thecla 1 Timothy and the Acts of Paul and Thecla have frequently been portrayed as opposite responses to women’s roles and authority within the church. Thecla presents a woman who travels to teach and preach the gospel, roles that depart from culturally accepted norms for women. By contrast, 1 Timothy advocates women returning to socially acceptable, passive roles.1 To take one example from a popular textbook, Bart Ehrman writes the following about attitudes toward women in the early church: “The Pastoral epistles present a stark contrast to the views set forth in The Acts of Paul and 1 In the 1980’s, MacDonald argued that 1 Timothy represents a community’s rejection of the active leadership of women found in the Acts of Paul and Thecla. Dennis Ronald MacDonald, The Legend and the Apostle: The Battle for Paul in Story and Canon (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1983). See also the works in this period by Virginia Burrus, Chastity as Autonomy: Women in the Stories of Apocryphal Acts (Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press, 1987); Stevan L. Davies, The Revolt of the Widows: The Social World of the Apocryphal Acts (Carbondale, Ill.: Southern Illinois University Press, 1980). More recently, scholars tend to see Thecla and 1 Timothy as independent literary works, but affirm that they take opposite stances regarding the roles of women and the emerging church structure. E.g., James W. Aageson, Paul, the Pastoral Epistles, and the Early Church (Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Publishers, 2008), 206. -

NT New Covenant Disciples Leaders Guide

Episcopal Curriculum for Youth NEW COVENTANT DISCIPLES Leader’s Guide Episcopal Curriculum for Youth—New Covenant Disciples Copyright © 2009 Virginia Theological Seminary i Copyright 2009 by Virginia Theological Seminary All rights reserved. All Scripture quotations are taken from the New Revised Standard Version, unless otherwise noted. Developed by Virginia Theological Seminary Center for the Ministry of Teaching 3737 Seminary Road Alexandria, VA 22304 Amelia J. Gearey Dyer, Ph.D., Editor-in-Chief Dorothy S. Linthicum, Managing Editor George J. Kroupa, III, Associate Editor Writers for Covenant Ancestors Linda Nichols The Rev. Gail Smith The Rev. John Palarine ISBN: 0-8192-6050-9 Episcopal Curriculum for Youth—New Covenant Disciples Copyright © 2009 Virginia Theological Seminary ii TABLE OF CONTENTS BACKGROUND FOR LEADERS Teaching Youth in Episcopal Churches...............................................1 Understanding Younger Youth.............................................................3 Who Are Leaders?................................................................................9 The Episcopal Curriculum for Youth ..................................................12 Using the Curriculum..........................................................................13 New Covenant Disciples ....................................................................15 NEW COVENANT DISCIPLES: SESSION TITLES Mary & Gabriel: Encounter with Mystery ...........................................17 Elizabeth & Mary: Someone to Talk To .............................................21 -

Even Apostles Get Discouraged

Even Apostles Get Discouraged Acts 18:1-22 Arrival in Corinth “After this Paul left Athens and went to Corinth.” (Acts 18:1, ESV) A Strategic Location “Even Apostles Get Discouraged” Temple of Apollo & Acrocorinth “Even Apostles Get Discouraged” 1 Corinthians 2:3 “And I was with you in weakness and in fear and much trembling.” (ESV) “Even Apostles Get Discouraged” Reason to Be Afraid •Persecution has taken its toll. “Even Apostles Get Discouraged” Reason to Be Afraid •Persecution has taken its toll. •Corinth is known as a wicked city. “Even Apostles Get Discouraged” Reason to Be Afraid •Persecution has taken its toll. •Corinth is known as a wicked city. •Paul is all alone. “Even Apostles Get Discouraged” Encouragement in Corinth Acts 18:2-11 Acts 18:2-4 “And he found a Jew named Aquila, a native of Pontus, recently come from Italy with his wife Priscilla, because Claudius had commanded all the Jews to leave Rome. And he went to see them, and because he was of the same trade he stayed with them and worked, for they were tentmakers by trade. And he reasoned in the synagogue every Sabbath, and tried to …” “Even Apostles Get Discouraged” Acts 18:4-7 “persuade Jews and Greeks. When Silas and Timothy arrived from Macedonia, Paul was occupied with the word, testifying to the Jews that the Christ was Jesus. And when they opposed and reviled him, he shook out his garments and said to them, ‘Your blood be on your own heads! I am innocent. From now on I will go to the Gentiles.’ And he left there …” “Even Apostles Get Discouraged” Acts 18:7-9 “and went to the house of a man named Titius Justus, a worshiper of God. -

Priscilla and Aquila Paul’S Firm Friends and Model Tentmakers by Mans Ramstad

Mans Ramstad 29 Priscilla and Aquila Paul’s Firm Friends and Model Tentmakers by Mans Ramstad n Acts and the Pauline letters around 95 individuals are recorded to have been associated with Paul during his ministry. They are participants Iin his preaching, teaching and writing. The presence of these people in Paul’s life shows the extent to which his ministry was one of teamwork and camaraderie, and was not a “one-man show”. Further analysis shows that of these 95 individuals, 36 of them were intimate coworkers of Paul (Hawthorne, Martin et al. 1993). Among the ranks of coworkers was the couple from Rome, Priscilla and Aquila. Paul referred to them as his syner- goi (coworkers), and they ministered together for a period of over ten years. During this time, Priscilla and Aquila1 ministered relatively independently of Paul, as he was often traveling or living in other locations, but their commitment to common ministry is sure. Although Paul is often considered the primary example of tentmaking ministry in the New Testament, and although the information we have on his ministry is the richest and most complete, we find among Paul’s friends other examples of good tentmaking ministry from which we can learn. I find Priscilla and Aquila to be excellent examples of how to be successful tentmak- ers and church planters in cross-cultural contexts. In this paper I would like to tell their life story as an example of successful tentmaking ministry. Background Aquila was a Jew born and raised in Pontus on the Black Sea coast of Asia Minor (Acts 18:1). -

Compatibility Mode

Graduate Program in Pastoral Ministries PMIN 206 The Synoptic Gospels Dr. Catherine Murphy THE CANON & THE APOCRYPHA Apocryphal Texts Some Definitions Apocrypha literally “hidden” in Greek, it refers to books judged at some point in time to be on the fringes of the canon Septuagint The Greek translation of the Hebrew/Aramaic scriptures (200 BCE), it includes 7+ books that became apocryphal for Jews and later for Protestants, who followed the Jewish canon; these books are part of Catholic Bibles Old Testament New Testament Tobit Wisdom Gospels Judith Sirach Epistles or letters 1-2 Maccabees Baruch Acts of various apostles One person’s apocrypha may Apocalypses be another person’s Bible Apocryphal Texts Some Examples Canonical NT Examples of Apocryphal Works • Gospels Egerton Papyrus, Gospel of Peter, Infancy Gospel of of James, Infancy Gospel of Thomas • Epistles or letters Epistles of Barnabas, Clement, Ignatius • Acts of apostles Acts of Paul and Thecla, Acts of Andrew, Acts of Peter • Apocalypses Apocalypse of Peter, Apocalypse of Paul The Definition of the Canon § Definition a Greek word for a tool of measurement; in scripture studies a list or catalogue of books that “measure up” to the standards of the church as authoritative texts § Time-Frame 4-gospel limit in some communities by 180 CE; earliest canon that matches our Nilometer NT’s is in 367 CE (Athanasius’ Easter Letter). § Criteria • apostolic, or traceable to one of the apostles • in traditional use, or in use from an early period in many churches • catholic, or universal -

Paul in Acts and Paul in His Letters

Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament Herausgeber / Editor Jörg Frey (Zürich) Mitherausgeber / Associate Editors Markus Bockmuehl (Oxford) James A. Kelhoffer (Uppsala) Hans-Josef Klauck (Chicago, IL) Tobias Nicklas (Regensburg) 310 Daniel Marguerat Paul in Acts and Paul in His Letters Mohr Siebeck Daniel Marguerat, born 1943; 1981 Habilitation; since 1984 Ordinary Professor of New Testa- ment, Faculty of Theology and Religious Studies, University of Lausanne; 2007–2008 President of the “Studiorum Novi Testamenti Societas”; since 2008 Professor Emeritus. ISBN 978-3-16-151962-8 / eISBN 978-3-16-157493-1 unveränderte eBook-Ausgabe 2019 ISSN 0512-1604 (Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum NeuenT estament) Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http: / /dnb.dnb.de. © 2013 by Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen, Germany. www.mohr.de This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher’s written permission. This applies particularly to reproduc- tions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was typeset by Martin Fischer inT übingen, printed by Gulde-Druck in Tübingen on non-aging paper and bound by Buchbinderei Spinner in Ottersweier. Printed in Germany. Preface This book is a collection of 13 essays devoted to Paul, however they follow the path of reverse chronology: starting with the reception of Paul and moving back to the apostle’s writings. The reason for this is revealed in the first chapter which acts as the program of this book: “Paul after Paul: a (Hi)story of Reception”. -

Priscilla and Aquila (Acts

Priscilla and Aquila ACTS 16:11-15 Baxter T. Exum (#1367) Four Lakes Church of Christ Madison, Wisconsin June 12, 2016 This morning I would like for us to continue in our series on great women in the Bible. Last week, of course, we looked at Lydia in the book of Acts. This morning I’d like for us to continue with a lesson on a woman who is mentioned six times in the Bible, and every time her name is mentioned, she is always mentioned along with her husband. They are never referred to separately, only together. And as far as I can tell, this is the only couple in the New Testament mentioned by name this many times and in a positive way. I am referring, of course, to Priscilla and Aquila. What I also find interesting about this couple is that in four out of the six references, Priscilla’s name is mentioned first. Some people have tried to make a big deal out of that – but the bottom line is: We do not know why her name is mentioned first in four out of the six references. As I was thinking about it this week, I concluded that if you were to stay in our house for a year and a half (as Paul did with them), you might refer to my wife first as well – she is much NICER than I am, and staying in the house with HER would be the good part of your stay. And so you might tell your friends, “I stayed at Keola’s house for 18 months…and there was this Baxter guy around there as well.” But really, we do not know what Paul and Luke had in mind with this. -

Volume 51 Issue 2

THE VOLUME 51 | ISSUE 2 | 2019 BIBLE METHODIST OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE BIBLE METHODIST CONNECTION OF CHURCHES Mentors A Crucial Component of the Christian Life THE BIBLE METHODIST VOLUME 51 | ISSUE 2 | 2019 EDITOR From the Rev. G. Clair Sams [email protected] SUBSCRIPTION MANAGER Editor Melba Sams 2235 Cale Switch Rd, Durant, OK 74701 [email protected] LAYOUT & DESIGN Shane Muir Mentor: a trusted counselor or guide. P.W. Keve, a pioneer [email protected] in the field of criminal justice wrote, “a mentor [is a person] who, because he is detached and disinterested, can hold up a PRINTING & CIRCULATION Country Pines, Inc. mirror to us.” www.countrypinesprinting.com This issue you will read articles that should challenge each of you. Historically, Christianity has known the importance The Bible Methodist is published four times a year. of influencing others in their walk with Christ and other It is the official publication of the Bible Methodist Connection of Churches. Christians. The Scriptures repeatedly remind us in the accounts of people highlighted and in the instructions given, Subscription price: $10 per year that discipleship is an extremely valuable tool. Too often we have failed to intentionally mentor or disciple BIBLE METHODIST others because of ignorance or indifference. The results of CONNECTION OF CHURCHES that lack produce inconsistency and confusion. Many people CONNECTIONAL CHAIRMAN in my generation simply assumed that their children or newly Dr. Michael Avery converted Christians would know what maturing Christians 3739 Moorhill Drive, Cincinnati, OH 45241 should embrace and reject. Because American culture had [email protected] for many years a strong Biblical foundation, many simply MISSIONS DIRECTOR assumed people would know the values of their faith.