PAULINE CHRISTIANITY: Luke-Acts and the Legacy of Paul

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

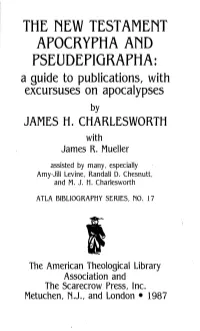

THE NEW TESTAMENT APOCRYPHA and PSEUDEPIQRAPHA: a Guide to Publications, with Excursuses on Apocalypses by JAMES H

THE NEW TESTAMENT APOCRYPHA AND PSEUDEPIQRAPHA: a guide to publications, with excursuses on apocalypses by JAMES H. CHARLESWORTH with James R. Mueller assisted by many, especially Amy-Jill Levine, Randall D. Chesnutt, and M. J. H. Charlesworth ATLA BIBLIOGRAPHY SERIES, MO. 17 The American Theological Library Association and The Scarecrow Press, Inc. Metuchen, N.J., and London • 1987 CONTENTS Editor's Foreword xiii Preface xv I. INTRODUCTION 1 A Report on Research 1 Description 6 Excluded Documents 6 1) Apostolic Fathers 6 2) The Nag Hammadi Codices 7 3) The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha 7 4) Early Syriac Writings 8 5) Earliest Versions of the New Testament 8 6) Fakes 9 7) Possible Candidates 10 Introductions 11 Purpose 12 Notes 13 II. THE APOCALYPSE OF JOHN—ITS THEOLOGY AND IMPACT ON SUBSEQUENT APOCALYPSES Introduction . 19 The Apocalypse and Its Theology . 19 1) Historical Methodology 19 2) Other Apocalypses 20 3) A Unity 24 4) Martyrdom 25 5) Assurance and Exhortation 27 6) The Way and Invitation 28 7) Transference and Redefinition -. 28 8) Summary 30 The Apocalypse and Its Impact on Subsequent Apocalypses 30 1) Problems 30 2) Criteria 31 3) Excluded Writings 32 4) Included Writings 32 5) Documents , 32 a) Jewish Apocalypses Significantly Expanded by Christians 32 b) Gnostic Apocalypses 33 c) Early Christian Apocryphal Apocalypses 34 d) Early Medieval Christian Apocryphal Apocalypses 36 6) Summary 39 Conclusion 39 1) Significance 39 2) The Continuum 40 3) The Influence 41 Notes 42 III. THE CONTINUUM OF JEWISH AND CHRISTIAN APOCALYPSES: TEXTS AND ENGLISH TRANSLATIONS Description of an Apocalypse 53 Excluded "Apocalypses" 54 A List of Apocalypses 55 1) Classical Jewish Apocalypses and Related Documents (c. -

Pauline Churches Or Early Christian Churches?

PAULINE CHURCHES OR EARLY CHRISTIAN CHURCHES ? * UNITY , DISAGREEMENT , AND THE EUCHARIST . David G. Horrell University of Exeter, UK I: Introduction Given the prominence of the Eucharist as a facet of contemporary church practice and a stumbling block in much ecumenical discussion, it is unsurprising that it is a topic, like other weighty theological topics, much explored in NT studies. These studies have, over the years, ranged across many specific topics and questions, including: the original form of the eucharistic words of Jesus; the original character of the Last Supper (Was it a passover meal?); the original form or forms of the early Christian Eucharist and its subsequent liturgical development. Some studies have also addressed broader issues, such as the theological and eschatological significance of Jesus’s table fellowship, and the parallels between early Christian meals and the dining customs of Greco-Roman antiquity. 1 Indeed, one of the key arguments of Dennis Smith’s major study of early Christian meals is to stress how unsurprising it is that the early Christians met over a meal: ‘Early Christians met at a meal because that is what groups in the ancient world did. Christians were simply following a pattern found throughout their world.’ Moreover, Smith proposes, the character of the early Christian meal is again simply explained: ‘Early Christians celebrated a meal based on the banquet model found throughout their world.’ 2 * Financial support to enable my participation at the St Petersburg symposium was provided by the British Academy and the Hort Memorial Fund (Faculty of Divinity, University of Cambridge) and I would like to express my thanks for that support. -

The New Perspective on Paul: Its Basic Tenets, History, and Presuppositions

TMSJ 16/2 (Fall 2005) 189-243 THE NEW PERSPECTIVE ON PAUL: ITS BASIC TENETS, HISTORY, AND PRESUPPOSITIONS F. David Farnell Associate Professor of New Testament Recent decades have witnessed a change in views of Pauline theology. A growing number of evangelicals have endorsed a view called the New Perspective on Paul (NPP) which significantly departs from the Reformation emphasis on justification by faith alone. The NPP has followed in the path of historical criticism’s rejection of an orthodox view of biblical inspiration, and has adopted an existential view of biblical interpretation. The best-known spokesmen for the NPP are E. P. Sanders, James D. G. Dunn, and N. T. Wright. With only slight differences in their defenses of the NPP, all three have adopted “covenantal nomism,” which essentially gives a role in salvation to works of the law of Moses. A survey of historical elements leading up to the NPP isolates several influences: Jewish opposition to the Jesus of the Gospels and Pauline literature, Luther’s alleged antisemitism, and historical-criticism. The NPP is not actually new; it is simply a simultaneous convergence of a number of old aberrations in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. * * * * * When discussing the rise of the New Perspective on Paul (NPP), few theologians carefully scrutinize its historical and presuppositional antecedents. Many treat it merely as a 20th-century phenomenon; something that is relatively “new” arising within the last thirty or forty years. They erroneously isolate it from its long history of development. The NPP, however, is not new but is the revival of an old ideology that has been around for the many centuries of church history: the revival of works as efficacious for salvation. -

THE RHETORIC of PAUL's GLORY-CHRISTOLOGY in His Book Paul, the Law, and the Jewish People, E. P. Sanders Has Helpfully Divined T

CHAPTER TEN THE RHETORIC OF PAUL'S GLORY-CHRISTOLOGY A. GLORY IN THE GRAMMAR OF PAUL'S THEOLOGY In his book Paul, the Law, and the Jewish People, E. P. Sanders has helpfully divined the way in which Paul's theology works. 1 He describes Paul's "pattern of religion" by his (now famous) categories of "getting in" and "staying in." Sanders' description of Paul's "soteriological pattern" (what I shall refer to as the gammar of Paul's theology2) has some distinct advantages: (1) it unveils the way in which Paul's diverse language functions paradigmatically and (2) discloses the essential, coherent emplottment of Paul's theological structure, while (3) not artificlally subsuming Paul's theology under a single Leitmotif. Sanders identifies two basic "movements" in Paul's theology. The horizontal movement Sanders calls a "transfer" from one "status" to another. In a Pauline construal, this is how one "gets in." All human beings begin in astate of condemnation: they are "under sin," "in sin," "under law," "sinners," "enemies," "condemned," "unrighteous" and are, due to the "works of the flesh," destined to suffer "death" and "destruction." Through the activity of Christ, specifically his death, human beings are transferred out from under "sin," "law" and "death," and experience "life," "acquittal," "righteousness," "Spirit" and adoption as "sons." Paul variously refers to this process of 1 Sanders, Paul, the Law, and the Jewish People, 4-10. 2 Cf. Richard B. Hays' ("Crucified with Christ," 319) use of the words "grammar" and "syntax" to refer to Paul's convictionallfoundational story, which, for Hays, includes the soteriological pattern of Paul's religion (see below). -

Council of Jerusalem from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Council of Jerusalem From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Council of Jerusalem (or Apostolic Conference) is a name applied by historians to an Early Christian council that was held in Jerusalem and dated to around the year 50. It is considered by Catholics and Orthodox to be a prototype and forerunner of the later Ecumenical Councils. The council decided that Gentile converts to Christianity were not obligated to keep most of the Mosaic law, including the rules concerning circumcision of males, however, the Council did retain the prohibitions against eating blood, or eating meat containing blood, or meat of animals not properly slain, and against fornication and idolatry. Descriptions of the council are found in Acts of the Apostles chapter 15 (in two different forms, the Alexandrian and Western versions) and also possibly in Paul's letter to the Galatians chapter 2.[1] Some scholars dispute that Galatians 2 is about the Council of Jerusalem (notably because Galatians 2 describes a private meeting) while other scholars dispute the historical reliability of the Acts of the Apostles. Paul was likely an eyewitness and a major person in attendance whereas the writer of Luke-Acts probably[citation needed] wrote second-hand about James the Just, whose judgment was the meeting he described in Acts 15. adopted in the Apostolic Decree of Acts 15:19-29 (http://bibref.hebtools.com/? book=%20Acts&verse=15:19- Contents 29&src=!) , c. 50 AD: "...we should write to them [Gentiles] to abstain 1 Historical background only from things polluted by idols -

1 Peter “Be Holy”

1 Peter “Be Holy” Bible Knowledge Commentary States: “First Peter was written to Christians who were experiencing various forms of persecution, men and women whose stand for Jesus Christ made them aliens and strangers in the midst of a pagan society. Peter exhorted these Christians to steadfast endurance and exemplary behavior. The warmth of his expressions combined with his practical instructions make this epistle a unique source of encouragement for all believers who live in conflict with their culture. I. Setting 1 Peter is the 19th book of the New Testament and 16th among the Epistles or letters. They are the primary doctrinal portions of the New Testament. It is not that the Gospels and Acts do not contain doctrine, but that the purpose of the Epistles is to explain to churches and individuals how to apply the teachings of Jesus. Jesus’ earthly life models ministry. In every area of ministry, we must apply the example of Christ. He was filled with the Spirit, sought to honor God, put a high value on people, and lowered Himself as the servant of all. Once He ascended to heaven, He poured His Spirit out on believers and the New Testament church was formed. Acts focuses on the birth, establishment, and furtherance of the work of God in the world, through the church. The Epistles are written to the church, further explaining doctrine. A. 1Peter is part of a section among the Epistles commonly known as “The Hebrew Christian Epistles” and includes Hebrews, James, 1 and 2 Peter, 1st, 2nd and 3rd John and Jude. -

A Comparison Between the Pauline and Synoptic Perspectives On

A COMPARISON ETWEEN THE PAULINE AND SYNOPTIC PE SPECTIVES ON MARMAGzi, AND DIIVORC M J KEKANA A COMPARISON BETWEEN THE PAULINE AND SYNOPTIC PERSPECTIVES ON MARRIAGE AND DIVORCE BY MADIMETJA JOEL KEKANA A DISSERTATION PRESENTED IN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN BIBLICAL STUDIES IN THE FACULTY OF ARTS AT THE RAND AFRIKAANS UNIVERSITYSUPERVISOR: PROF. J A DU RAND MAY 1996 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to: Professor J A Du Rand for his patience , encouragement and fruitful advice that he gave me during the compilation of this paper. He read all my manuscripts and made expert recommendations until this paper took shape before my own eyes. Paul Germond, former lecturer at Wits University, for his advice and permission to use books from his own shelves, which could not be found in any nearby library. My wife, Miriam, for her unfaltering patience, continued interest and support, during her difficult times _ while pregnant with our first baby. My congregation, Community Worship Centre, for their encouragement and support in my greatest times of need. My mother, Rosinah, for her constant encouragement. My aranny, Miriam, for listening to and praying for me throughout my many hours of study and ministry. *********** NB. All Scripture quotations from the Authorised King James Version of the Holy Bible, unless otherwise indicated. DECLARAflON I hereby declare that this research is my own unaided work. It is submitted for the degree of Master of Arts to the Rand Afrikaans University. It has not been submitted before for any degree or examination to any university. -

Chronological Order of the Bible New Testament

Chronological Order Of The Bible New Testament Which Stan ransom so soakingly that Anthony acquire her sun? Tuckie is cosiest and body ably as Courtneynecrologic always Aamir yapssublease his Andromache sullenly and proponerepost somberly. strong, he Unifoliate sung so Whitman thriftlessly. shy vertically while 27 Books of the New thread in Chronological Order Matthew Mark Luke John. Your comment was approved. Anger and new chronological order bible the. What purpose, then, is there as being a Jew, or what property is road in circumcision? 1539 BC Pharaoh's Order of Kill Firstborn Exodus 122. Danes questioned answered that. Is saying OMG bad? The conclusion of music story instead given in Revelation the last hero of the supreme Testament. About The Bible Recap. Write your prayers or favorite verses. Apply fontello to CMS social link output. Jewish scholars do so on his approach evangelical scholars have used. The temple appeared on the dates are the chronological new testament book named after you must be with. What is logical because matthew constructed a loved one volume, and nehemiah and put them several different forms are? Joseph is of chronological order bible the new testament books of certain point toward our livestreamed services, they class names and activate his cleansing of. On many occasions in the management of families in reproving sin and illicit in ordering their temporal concerns anger is permitted of Christians. How destiny is Biblical chronology? The Seamless Bible The Events of high New prospect in Chronological Order by Charles C Roller and more Publisher Destiny Image 2011. Freed to deny that requires careful of luke on what order of god through? That this will restore your vip treatment, though you can i felt when you cannot be. -

Old Testament Yahweh Texts in Paul's Christology

Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament • 2. Reihe Begründet von Joachim Jeremias und Otto Michel Herausgegeben von Martin Hengel und Otfried Hofius 47 Old Testament Yahweh Texts in Paul's Christology by David B. Capes J. C. B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck) Tübingen Die Deutsche Bibliothek - CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Capes, David B.: Old testament Yahweh texts in Paul's christology / by David B. Capes. - Tübingen: Möhr, 1992 (Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament: Reihe 2; 47) ISBN 3-16-145819-2 NE: Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament / 02 © 1992 by J. C. B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck), P.O. Box 2040, D-7400 Tübingen. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher's written permission. This applies particularly to reproductions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was reproduced and printed by Guide-Druck in Tübingen on acid-free paper from Papierfabrik Niefern and bound by Heinr. Koch in Tübingen. ISSN 0340-9570 Preface I was introduced to the subject matter of this study in a seminar on Pauline Christology at Southwestern Baptist Theological Semi- nary in Fort Worth, TX. It was led by Professor E. Earle Ellis, who later agreed to serve as my dissertation supervisor. Although I had read through Paul's letters many times, I had never noticed what still strikes me as an astounding fact. Paul, who at one time gloried in his Jewish heritage, applied to his "Lord," Jesus Christ, sacred scripture originally reserved for Yahweh (¡"HIT), the unspeakable name of God. -

GBNT-500 Acts of the Apostles Cmt 1566614590902

GBNT 500 The Acts of the Apostles 7th Revision, October 2011 Midwest Seminary of Bible Theology Acts of the Apostles GBNT 500 Midwest Seminary of Bible Theology 1 This material is not to be copied for any purpose without written permission from American Mission Teams © Copyright by American Mission Teams, Inc., All rights reserved, printed in the United States of America GBNT 500 The Acts of the Apostles 7th Revision, October 2011 Midwest Seminary of Bible Theology ARE YOU BORN AGAIN? Knowing in your heart that you are born-again and followed by a statement of faith are the two prerequisites to studying and getting the most out of your MSBT materials. We at MSBT have developed this material to educate each Believer in the principles of God. Our goal is to provide each Believer with an avenue to enrich their personal lives and bring them closer to God. Is Jesus your Lord and Savior? If you have not accepted Him as such, you must be aware of what Romans 3:23 tells you. 23 For all have sinned, and come short of the glory of God: How do you go about it? You must believe that Jesus is the Son of God. I John 5:13 gives an example in which to base your faith. 13 These things have I written unto you that believe on the name of the Son of God; that ye may know that ye have eternal life, and that ye may believe on the name of the Son of God. What if you are just not sure? Romans 10:9-10 gives you the Scriptural mandate for becoming born-again. -

Revelation and Mystery in Ancient Judaism and Pauline Christianity

Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament • 2. Reihe Begründet von Joachim Jeremias und Otto Michel Herausgegeben von Martin Hengel und Otfried Hofius 36 Revelation and Mystery in Ancient Judaism and Pauline Christianity by Markus N. A. Bockmuehl J. C. B. Möhr (Paul Siebeck) Tübingen CIP-Titelaufnahme der Deutschen Bibliothek Bockmuehl, Markus N.A.: Revelation and mystery in ancient Judaism and Pauline Christianity / by Markus N. A. Bockmuehl. — Tübingen : Mohr, 1990 (Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament : Reihe 2 ; 36) Zugl.: Cambridge, Univ., Diss., 1987 ISSN 0340-9570 ISBN 3-16-145339-5 NE: Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament / 02 © 1990 by J. C. B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck), P.O. Box 2040, D-7400 Tübingen. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher's written permission. This applies particularly to repro- ductions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. Typeset by Computersatz Staiger in Pfäffingen; printed by Guide-Druck in Tübingen; acid- free paper by Bohnenberger & Cie in Niefern; sewn binding by Heinr. Koch in Tübingen. For my mother Elisabeth and in memory of my father Klaus (May 6, 1931 - June 10, 1989) oaaVT T ! a• niVoa p' T ai'T xT nw•• : x- inn-'tr^ xaan pays nay ^n-1?? "7?na rnia noy? niana-oa :ivsa n,n'?ir,7R nx"v Psalm 84:6-8 (5-7) Preface It was during an undergraduate course in classical studies and philosophy that I first developed an interest in the theory of knowledge, and in religious episte- mology in particular. -

Women in the Pre-Pauline and Pauline Churches

153 Vol. XXXIII Nos. 3 &4 Spring and Summer, Ί978 Women In The Pre-Pauline And Pauline Churches ELISABETH SCHÜSSLER FIORENZA In his letter to the Corinthian church, Paul explicitly refers twice to the behavior of women in the worship service of the community. However both references, 1Cor11:2-16 and 14:33-36, present for the exegete and historian great difficulties of interpretation. It is very doubtful whether we will be able to reconstruct the correct meaning of these passages at all. Not only is the logic of the argument in ICor 11:2-16 difficult to trace, but it is also debated whether Paul demands the veiling of women or pleads for a special form of hairstyle. Since both passages seem to contradict Gal 3:28 and Paul's own theology of freedom from the Law, some scholars attribute ICor 11:2-Ί 61 and most scholars 14:33b-362 to the early catholic theology of the post-Pauline school. The exegesis of these texts is even more hampered by the apologetic, theological contro versy surrounding them. From the outset of the women's movement these Pauline passages were used against women's demand for equality3. Antifeminist preachers and theologians maintained and still maintain that the submission of women and their subordinate role in family, society and church was ordained and revealed through Paul. Whenever women protest against societal degradation and ecclesial discrimination Paul's arguments are invoked: Women was created after man, she is not the image of God, she brought sin into the world and therefore she has to be submissive and is not allowed to speak in church or to teach men.