JETS) Is a Refereed Journal Published Biannu- Ally (Fall and Spring)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brief Regarding the Future of Regional News Submitted to The

Brief Regarding the Future of Regional News Submitted to the Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage By The Fédération nationale des communications – CSN April 18, 2016 Contents Contents ............................................................................................................................................................................ 3 Foreword .......................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................... 5 The role of the media in our society ..................................................................................................................... 7 The informative role of the media ......................................................................................................................... 7 The cultural role of the media ................................................................................................................................. 7 The news: a public asset ............................................................................................................................................ 8 Recent changes to Quebec’s media landscape .................................................................................................. 9 Print newspapers .................................................................................................................................................... -

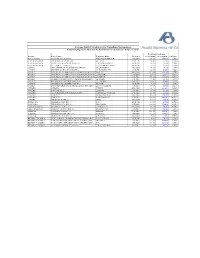

Average Daily Circulation for Canadian Newspapers Preliminary Figures As Filed with the Audit Bureau of Circulations -- Subject to Audit

Average Daily Circulation for Canadian Newspapers Preliminary Figures as Filed with the Audit Bureau of Circulations -- Subject to Audit Total Paid Circulation Province City (County) Newspaper Name Frequency As of 9/30/09 As of 9/30/08 % Change NOVA SCOTIA HALIFAX (HALIFAX CO.) CHRONICLE-HERALD AVG (M-F) 108 182 110 875 -2,43% NEW BRUNSWICK FREDERICTON (YORK CO.) GLEANER MON-FRI 20 863 21 553 -3,20% NEW BRUNSWICK MONCTON (WESTMORLAND CO.) TIMES-TRANSCRIPT MON-FRI 36 115 36 656 -1,48% NEW BRUNSWICK ST. JOHN (ST. JOHN CO.) TELEGRAPH-JOURNAL MON-FRI 32 574 32 946 -1,13% QUEBEC CHICOUTIMI (LE FJORD-DU-SAGUENAY) LE QUOTIDIEN AVG (M-F) 26 635 26 996 -1,34% QUEBEC GRANBY (LA HAUTE-YAMASKA) LA VOIX DE L'EST MON-FRI 14 951 15 483 -3,44% QUEBEC MONTREAL (COMMUNAUTE-URBAINE -DE-MONTREAL)GAZETTE AVG (M-F) 147 668 143 782 2,70% QUEBEC MONTREAL (COMMUNAUTE-URBAINE- DE-MONTREAL)LE DEVOIR AVG (M-F) 26 099 26 181 -0,31% QUEBEC MONTREAL (COMMUNAUTE-URBAINE- DE-MONTREAL)LA PRESSE AVG (M-F) 198 306 200 049 -0,87% QUEBEC QUEBEC (COMMUNAUTE- URBAINE-DE-QUEBEC) LE SOLEIL AVG (M-F) 77 032 81 724 -5,74% QUEBEC SHERBROOKE (SHERBROOKE CO.) LA TRIBUNE AVG (M-F) 31 617 32 006 -1,22% QUEBEC SHERBROOKE (SHERBROOKE CO.) RECORD MON-FRI 4 367 4 539 -3,79% QUEBEC TROIS-RIVIERES (FRANCHEVILLE CEN. DIV. (MRC) LE NOUVELLISTE AVG (M-F) 41 976 41 886 0,21% ONTARIO OTTAWA CITIZEN AVG (M-F) 118 373 124 654 -5,04% ONTARIO OTTAWA-HULL LE DROIT AVG (M-F) 35 146 34 538 1,76% ONTARIO THUNDER BAY (THUNDER BAY DIST.) CHRONICLE-JOURNAL AVG (M-F) 25 495 26 112 -2,36% ONTARIO TORONTO GLOBE AND MAIL AVG (M-F) 301 820 329 504 -8,40% ONTARIO TORONTO NATIONAL POST AVG (M-F) 150 884 190 187 -20,67% ONTARIO WINDSOR (ESSEX CO.) STAR AVG (M-F) 61 028 66 080 -7,65% MANITOBA BRANDON (CEN. -

Prescribed by Law/Une Règle De Droit©

PRESCRIBED BY LAW/UNE RÈGLE © DE DROIT ∗ ROBERT LECKEY In Multani, the Supreme Court of Canada’s Dans l’affaire Multani sur le port du kirpan, les kirpan case, judges disagree over the proper juges de la Cour suprême du Canada exprimèrent approach to reviewing administrative action under leur désaccord au sujet de l’approche adéquate au the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The contrôle des décisions administratives en vertu de la concurring judges questioned the leading judgment, Charte canadienne des droits et libertés. Les juges Slaight Communications, on the basis that it is minoritaires remirent en question l’arrêt Slaight inconsistent with the French text of section 1. This Communications, arguant que ce précédent était disagreement stimulates reflections on language and incompatible avec la version française de l’article culture in Canadian constitutional and administrative premier de la Charte. Ce désaccord soulève des law. A reading of both language versions of section 1, réflexions au sujet du rôle du langage et de la culture Slaight, and the critical scholarship reveals a au sein du droit constitutionnel et administratif linguistic dualism in which scholars read one version canadien. Une lecture des versions anglaise et of the Charter and of the judgment and write about française de l’article premier et de Slaight et de la them in that language. The separate streams doctrine revèle un dualisme linguistique par lequel undermine the idea of a shared, bilingual public law. les juristes lisent une seule version de la Charte et du Yet the differences exceed language. The article jugement et les commentent en cette même langue. -

Sherbrooke : Sa Place Dans La Vie De Relations Des Cantons De L’Est Pierre Cazalis

Document généré le 1 oct. 2021 05:11 Cahiers de géographie du Québec Sherbrooke : sa place dans la vie de relations des Cantons de l’Est Pierre Cazalis Volume 8, numéro 16, 1964 Résumé de l'article Because they are due to economic contingencies rather than to unfavourable URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/020498ar natural conditions, present-day regional disparities compel the geographer to DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/020498ar modify his concept of the region. Whereas in the past the region was considered essentially as a physical entity, to many authors it appears today to Aller au sommaire du numéro be « a functional area, based on communication and exchange, and as such defined less by its limits than by its centre » (Juillard). It is this concept which will be used in regional planning. Éditeur(s) Taking the city of Sherbrooke as a nodal centre, the author attempts to define such a region through an analysis and graphical representation of the Département de géographie de l'Université Laval complementary roles in influence and attraction played by the city in the fundamental aspects of employment, trade, finance, education, ISSN communication, health and government. Although it is already well-developed in the secondary sector, with more than 9,000 workers employed in industry 0007-9766 (imprimé) and an annual production worth more than $100 million, Sherbrooke bas a 1708-8968 (numérique) power of attraction and influence which is due essentially to its tertiary sector : wholesale trade, insurance, education, communication. Ac-cording to the Découvrir la revue criteria mentioned above, the area dominated by Sherbrooke includes the whole of the following counties : Sherbrooke, Stanstead, Richmond, Wolfe and Compton ; and the greater part of Frontenac, Mégantic, Artbabaska, Citer cet article Drummond and Brome counties. -

030140236.Pdf

UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC MÉMOIRE PRÉSENTÉ À L'UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À TROIS-RIVIÈRES COMME EXIGENCE PARTIELLE DE LA MAÎTRISE EN ÉTUDES QUÉBÉCOISES PAR CATHERINE LAMPRON-DESAULNIERS LA VIE CULTURELLE À TROIS-RIVIÈRES DANS LES ANNÉES 1960 : DÉMOCRATISA TI ON DE LA CUL TURE, DÉMOCRATIE CUL TU REL LE ET CUL TURE JEUNE. HISTOIRE D'UNE TRANSITION MARS 2010 Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières Service de la bibliothèque Avertissement L’auteur de ce mémoire ou de cette thèse a autorisé l’Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières à diffuser, à des fins non lucratives, une copie de son mémoire ou de sa thèse. Cette diffusion n’entraîne pas une renonciation de la part de l’auteur à ses droits de propriété intellectuelle, incluant le droit d’auteur, sur ce mémoire ou cette thèse. Notamment, la reproduction ou la publication de la totalité ou d’une partie importante de ce mémoire ou de cette thèse requiert son autorisation. RÉSUMÉ L'objectif principal de cette recherche vise à mettre en lumière la transition culturelle qui s'effectue à Trois-Rivières au cours des années 1960. Le milieu culturel se transforme à plusieurs niveaux: les lieux de diffusion culturelle, les acteurs ainsi que la programmation culturelle en sont des exemples. L'analyse démontre tout le processus de démocratisation de la culture cultivée pris en charge par l'élite ainsi que l'émergence, à la fin de la décennie, de la démocratie culturelle mise de l'avant par une jeunesse qui sait s'imposer. Ces deux groupes ont su démontrer les caractéristiques dominantes de la diffusion de la culture cultivée dans une ville moyenne comme Trois-Rivières. -

Directors' Report to Shareholders

Directors’ Report to Shareholders The Power Corporation family of companies and investments had a very strong year in 2011, with stable results from the financial services businesses and a meaningful contribution from investing activities. While 2011 showed continued progress in global economic recovery, the year was nonetheless challenging. Interest rates were low and the economy and equity markets showed progress during the first half. This largely reversed itself during the second half of the year. Our results indicate that we have the risk-management culture, capital and liquidity to navigate these economic conditions successfully and that investment gains represent an attractive upside to our business. 2011 $499.6 $1,152 $574 BILLION MILLION MILLION CONSOLIDATED OPERATING DIVIDENDS ASSETS AND EARNINGS DECLARED ASSETS UNDER ATTRIBUTABLE TO MANAGEMENT PARTICIPATING SHAREHOLDERS Mission 13.0% $2.50 $1.16 Enhancing shareholder value RETURN ON OPERATING DIVIDENDS by actively managing operating EQUITY EARNINGS DECLARED BASED ON PER PER businesses and investments which OPERATING PARTICIPATING PARTICIPATING EARNINGS SHARE SHARE can generate long-term, sustainable growth in earnings and dividends. Value is best achieved through a prudent approach to risk and through responsible corporate citizenship. Power Corporation aims to act like an owner with a long-term perspective and a strategic vision anchored in strong core values. 6 POWER CORPORATION OF CANADA 2011 ANNUAL REPORT Power Corporation’s financial services companies are focused on providing protection, asset management, and retirement savings products and services. We continue to believe that the demographic trends affecting retirement savings, coupled with strong evidence that advice from a qualified financial advisor creates added value for our clients, reinforce the soundness of our strategy of building an advice-based multi-channel distribution platform in North America. -

2021 Ownership Groups - Canadian Daily Newspapers (74 Papers)

2021 Ownership Groups - Canadian Daily Newspapers (74 papers) ALTA Newspaper Group/Glacier (3) CN2i (6) Independent (6) Quebecor (2) Lethbridge Herald # Le Nouvelliste, Trois-Rivieres^^ Prince Albert Daily Herald Le Journal de Montréal # Medicine Hat News # La Tribune, Sherbrooke^^ Epoch Times, Vancouver Le Journal de Québec # The Record, Sherbrooke La Voix de l’Est, Granby^^ Epoch Times, Toronto Le Soleil, Quebec^^ Le Devoir, Montreal Black Press (2) Le Quotidien, Chicoutimi^^ La Presse, Montreal^ SaltWire Network Inc. (4) Red Deer Advocate Le Droit, Ottawa/Gatineau^^ L’Acadie Nouvelle, Caraquet Cape Breton Post # Vancouver Island Free Daily^ Chronicle-Herald, Halifax # The Telegram, St. John’s # Brunswick News Inc. (3) The Guardian, Charlottetown # Times & Transcript, Moncton # Postmedia Network Inc./Sun Media (33) The Daily Gleaner, Fredericton # National Post # The London Free Press Torstar Corp. (7) The Telegraph-Journal, Saint John # The Vancouver Sun # The North Bay Nugget Toronto Star # The Province, Vancouver # Ottawa Citizen # The Hamilton Spectator Continental Newspapers Canada Ltd.(3) Calgary Herald # The Ottawa Sun # Niagara Falls Review Penticton Herald The Calgary Sun # The Sun Times, Owen Sound The Peterborough Examiner The Daily Courier, Kelowna Edmonton Journal # St. Thomas Times-Journal St. Catharines Standard The Chronicle Journal, Thunder Bay The Edmonton Sun # The Observer, Sarnia The Tribune, Welland Daily Herald-Tribune, Grande Prairie The Sault Star, Sault Ste Marie The Record, Grand River Valley F.P. Canadian Newspapers LP (2) The Leader-Post, Regina # The Simcoe Reformer Winnipeg Free Press The StarPhoenix, Saskatoon # Beacon-Herald, Stratford TransMet (1) Brandon Sun Winnipeg Sun # The Sudbury Star Métro Montréal The Intelligencer, Belleville The Daily Press, Timmins Glacier Media (1) The Expositor, Brantford The Toronto Sun # Times Colonist, Victoria # The Brockville Recorder & Times The Windsor Star # The Chatham Daily News The Sentinel Review, Woodstock Globe and Mail Inc. -

Les Aides Publiques À La Presse Écrite

Étude Les aides publiques à la presse écrite Produit par MCE Conseils pour la Fédération nationale des communications – CSN Octobre 2017 LES AIDES PUBLIQUES À LA PRESSE ÉCRITE Contrairement à plusieurs pays d’Europe, l’aide gouvernementale directe aux journaux imprimés ou numériques est pratiquement exclue des nombreux programmes d’aide en vigueur au Canada. Les périodiques, par exemple, reçoivent un soutien du fédéral, et les médias communautaires, l’aide de Québec. Seuls l’Ontario et le Québec ont ouvert cette porte depuis peu à la presse écrite quotidienne, entre autres, pour soutenir le virage numérique. Dans le dernier budget provincial, le gouvernement québécois a annoncé des mesures totalisant 24 M$ sur cinq ans pour soutenir le virage numérique des médias d’ici et 12 M$ de plus pour absorber les coûts de la taxe sur le recyclage. QUELQUES CHIFFRES : En 2016, le Canada comptait : 103 journaux quotidiens imprimés et leur site Internet (soit 19 de moins qu’en 2011) : . 90 quotidiens payants; . 13 quotidiens gratuits. VARIATION PROVINCE/TERRITOIRE NB DE TITRES 2016 NB DE TITRES 2011 5 ANS AB 11 13 -2 BC 14 25 -11 MB 4 4 - NB 4 4 - NL 2 2 - NS 5 6 -1 ON 43 47 -4 PE 2 2 - QC 13 14 -1 SK 4 4 - YT 1 1 - Canada 103 122 -19 Les quotidiens publient plus de 30 millions d’exemplaires chaque semaine. Les principaux quotidiens francophones sont : LE DEVOIR (Montréal) LE QUOTIDIEN (Saguenay) LE DROIT (Ottawa) LE SOLEIL (Québec) LE JOURNAL DE MONTRÉAL LA TRIBUNE (Sherbrooke) LE JOURNAL DE QUÉBEC LA VOIX DE L'EST (Granby) LE NOUVELLISTE (Trois-Rivières) L'ACADIE NOUVELLE (Nouveau-Brunswick) LA PRESSE (Montréal) 1 1 060 journaux régionaux hebdomadaires imprimés et leur site Internet. -

La Compagnie D'assurance Du Canada Sur La

La Compagnie d’Assurance du Canada sur la Vie A vis de convocation à l’assemblée BOOVFMMFEFTǂBDUJPOOBJSFT FUEFTǂUJUVMBJSFTEFQPMJDFEF Circulaire de sollicitation de procurations de la direction La Compagnie d’Assurance du Canada sur la Vie Siège social : Winnipeg (Manitoba) AVIS DE CONVOCATION À NOTRE ASSEMBLÉE ANNUELLE DES ACTIONNAIRES ET DES TITULAIRES DE POLICE DE 2020 Vous êtes invité à notre assemblée annuelle des actionnaires et des titulaires de police de 2020. Quand : Le jeudi 7 mai 2020 à 11 h (heure du Centre) Où : 100, rue Osborne Nord Winnipeg (Manitoba) Ordre du jour de l’assemblée : (1) recevoir les états financiers et les rapports de l’auditeur et de l’actuaire pour l’exercice clos le 31 décembre 2019; (2) élire les administrateurs représentant les titulaires de police; (3) nommer lesauditeurs; (4) régler les autres questions dûment soumises à l’assemblée. L’assemblée annuelle de Great-West Lifeco Inc. aura lieuau même moment et aumême endroit. Par ordre du conseil d’administration, le vice-président principal, secrétaire général et chef de la gouvernance, Winnipeg (Manitoba) Le 9 mars 2020 Jeremy W. Trickett Nous surveillons de pre`s l’e´volution de la situation du coronavirus (COVID-19); nous sommes sensibles aux inquie´tudes de nos actionnaires et de nos titulaires de police ence qui concerne lasante´ publique et les de´placements et sommesattentifs auxprotocoles qui pourraient eˆtre impose´s par les gouvernements fe´de´ral, provinciaux et locaux. Vous pouvez visionner l’assemble´e en direct au moyen de la webe´mission diffuse´e surle site Webcanadavie.com ouun enregistrement decelle-ci apre`s latenue de l’assemble´e. -

Rapport Final

Rapport final Analyse sur l’état de l’information locale au Québec présentée au Syndicat canadien de la fonction publique (SCFP) Influence Communication 1er février 2016 Influence Communication 505, boul. de Maisonneuve Ouest, Bureau 200 Montréal ( Québec ) H3A 3C2 1— Description du projet À la demande du SCFP, Influence Communication a réalisé un mandat d’analyse afin de dresser le portrait de l’information locale au Québec en 2001 et en 2015. 2— Méthodologie L’ensemble des données repose sur la collecte quotidienne d’information par Influence Communication dans les médias traditionnels du Québec, tant en anglais qu’en français : quotidiens, hebdos, magazines, radio, télévision et sites Web d’information. Le concept de poids médias ou de mesure utilisé dans la présente analyse est un indice quantitatif développé par Influence Communication. Il permet de mesurer la place qu’un individu, une organisation, un événement, une nouvelle ou un thème occupe dans un marché donné. Il ne tient pas compte de la valeur des arguments, ni du ton de la couverture. Les secteurs qui ne sont pas considérés sont : • les jeux télévisés • la publicité • les petites annonces • la chronique nécrologique • le cinéma Méthodologie du tableau 4,1 et 4,3 L’intérêt pour l’information régionale a été calculé en évaluant la totalité de l’intérêt pour une région, tout en évitant l’information dans la région propre. À titre d’exemple, nous avons analysé la somme de l’intérêt des médias de Saguenay pour les régions en excluant la couverture sur Saguenay afin d’éviter de fausser les résultats. Nous plaçons ensuite la somme du contenu régional sur l’ensemble de l’information au Québec pour obtenir les résultats. -

À Sherbrooke

Coup de théâtre qui pourrait Quelques incidents ont marqué la nuit à Sherbrooke Couronnes de fleurs SHERBROOKE — Plusieurs événe Selon quelques informations, il ap rait, elle aussi, occasionné des pro ments ont marque les premières heu pert qu'un individu aurait subit des blèmes au niveau des installations élec venant du cimetière res du matin à Sherbrooke. blessures aux coins des rues King et triques. Il nous a été possible de cons En premier lieu, un vol avec ef Ontario durant la nuit. On ignore pour tater de visu que la rue Wellington dénouer la crise jordanienne fraction aurait été commis dans le l’instant la cause des blessures qui nord s’est retrouver dans l’obscurité jetées dans un fossé quartier est de la ville au cours de la pourraient être dues à un chauffard pendant quelques minutes. D'autres nuit, mais il a été impossible d'oble- aussi bien que découler d'une bagarre. problèmes similaires ont dû se produi nir des rer. eignements supplémentai re ailleurs dans les limites de la cité (page 16) res, l'enquête étant en cours. L’orage qui a éclaté vers 3h., au- vu l’ampleur de l’orage. (page 3) iril. SHERBROOKE W.ft.ADAM im PURE MILK HUILE A CHAUFFAGE POELES et FOURNAISES PRODUITS LAITIERS SUPERIEURS _______ 569-9744_______ SERVICE COURTOIS METEO — Duna les Canton^ de l’Est ensoleille avec périodes nuageuses averses et orages au cours de I après-midi ou de la soiree chaud LIVRAISON A TOUS LES JOURS Minimum a Sherbrooke 5i a 60 Maximum de 75 a J»0 Apei\u pour samedi ensoleille et chaud „ Tel. -

TABLOID NOUVEAU GENRE Format Change and News Content in Quebec City's Le Soleil

TABLOID NOUVEAU GENRE Format change and news content in Quebec City’s Le Soleil Colette Brin and Genevie`ve Drolet Faced with growing competition and dwindling readership, especially among young people, some metropolitan newspapers have switched from a broadsheet to a smaller, easier to handle format. This strategy has been successful at least in the short term, and has been applied recently in Quebec by small-market newspapers owned by the Gesca chain. In April 2006, Le Soleil, the second-largest daily of the group, adopted a compact format and new design, accompanied by new content sections, changes in newsroom staff and management, as well as an elaborate marketing plan. In announcing the change to its readers, an article by the editor-in-chief focused on adapting the newspaper’s content to readers’ lifestyles and interests, as well as developing interactivity. The plan was met with some resistance in the newsroom and among readers. Based on a theoretical model of long-term change in journalism, briefly set out in the article, this study analyzes this case as it compares to the ‘‘communication journalism’’ paradigm. Specifically, it examines how tensions between competing conceptions of journalism are manifest in Le Soleil’s own coverage of the format change. KEYWORDS communication journalism; format change; journalism history; journalistic meta- discourse; newspapers; tabloidization Introduction A Newspaper’s Response to Changing Times: Format Change in Historical* Perspective After more than a century of publication as a broadsheet,