Quebec's Filiation Regime, the Roy Report's Recommendations, and the 'Interest of the Child'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ntract Law Eform in Quebec

Vol . 60 September 1982 Septembre No . 3 NTRACT LAW EFORM IN QUEBEC P.P.C . HAANAPPEL* Montreal I. Introduction . Most of the law of contractual obligations in Quebec is contained in 1982 CanLIIDocs 22 the Civil Code of Lower Canada of 1966. 1 As is the case with the large majority of civil codes in the world, the Civil Code of Quebec was conceived, written and brought into force in a pre-industrialized environment. Its philosophy is one of individualism and economic liberalism . Much has changed in the socio-economic conditions of Quebec since 1866. The state now plays a far more active and im- portant role in socio-economic life than it did in the nineteenth century. More particularly in the field of contracts, the principle of equality of contracting parties or in.other words the principle of equal bargaining power has been severely undermined . Economic distribution chan- nels have become much longer than in 1866, which has had a pro- found influence especially on the contract of sale. Today products are rarely bought directly from their producer, but are purchased through one or more intermediaries so that there will then be no direct con- tractual link between producer (manufacturer) and user (consumer).' Furthermore, the Civil Code of 1866 is much more preoccupied with immoveables (land and buildings) than it .is with moveables (chat- tels) . Twentieth century commercial transactions, however, more often involve moveable than immoveable objects . * P.P.C. Haanappel, of the Faculty of Law, McGill University, Montreal. This article is a modified version of a paper presented by the author to ajoint session of the Commercial and Consumer Law, Contract Law and Comparative Law Sections of the 1981 Conference of the Canadian Association of Law Teachers. -

Res Extra Commercium and the Barriers Faced When Seeking the Repatriation and Return of Potent Cultural Objects

American Indian Law Journal Volume 4 Issue 2 Article 5 May 2017 Res Extra Commercium and the Barriers Faced When Seeking the Repatriation and Return of Potent Cultural Objects Sara Gwendolyn Ross Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/ailj Part of the Cultural Heritage Law Commons, Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Ross, Sara Gwendolyn (2017) "Res Extra Commercium and the Barriers Faced When Seeking the Repatriation and Return of Potent Cultural Objects," American Indian Law Journal: Vol. 4 : Iss. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/ailj/vol4/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications and Programs at Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Indian Law Journal by an authorized editor of Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Res Extra Commercium and the Barriers Faced When Seeking the Repatriation and Return of Potent Cultural Objects Cover Page Footnote Sara Ross is a Ph.D. Candidate and Joseph-Armand Bombardier CGS Doctoral Scholar at Osgoode Hall Law School in Toronto, Canada. Sara holds five previous degrees, including a B.A. in French Language and Literature from the University of Alberta; B.A. Honours in Anthropology from McGill; both a civil law degree (B.C.L.) and common law degree (L.L.B.) from the McGill Faculty of Law; and an L.L.M, from the University of Ottawa. -

Brief Regarding the Future of Regional News Submitted to The

Brief Regarding the Future of Regional News Submitted to the Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage By The Fédération nationale des communications – CSN April 18, 2016 Contents Contents ............................................................................................................................................................................ 3 Foreword .......................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................... 5 The role of the media in our society ..................................................................................................................... 7 The informative role of the media ......................................................................................................................... 7 The cultural role of the media ................................................................................................................................. 7 The news: a public asset ............................................................................................................................................ 8 Recent changes to Quebec’s media landscape .................................................................................................. 9 Print newspapers .................................................................................................................................................... -

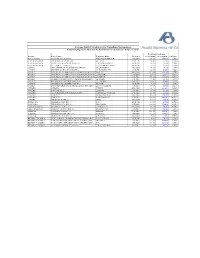

Average Daily Circulation for Canadian Newspapers Preliminary Figures As Filed with the Audit Bureau of Circulations -- Subject to Audit

Average Daily Circulation for Canadian Newspapers Preliminary Figures as Filed with the Audit Bureau of Circulations -- Subject to Audit Total Paid Circulation Province City (County) Newspaper Name Frequency As of 9/30/09 As of 9/30/08 % Change NOVA SCOTIA HALIFAX (HALIFAX CO.) CHRONICLE-HERALD AVG (M-F) 108 182 110 875 -2,43% NEW BRUNSWICK FREDERICTON (YORK CO.) GLEANER MON-FRI 20 863 21 553 -3,20% NEW BRUNSWICK MONCTON (WESTMORLAND CO.) TIMES-TRANSCRIPT MON-FRI 36 115 36 656 -1,48% NEW BRUNSWICK ST. JOHN (ST. JOHN CO.) TELEGRAPH-JOURNAL MON-FRI 32 574 32 946 -1,13% QUEBEC CHICOUTIMI (LE FJORD-DU-SAGUENAY) LE QUOTIDIEN AVG (M-F) 26 635 26 996 -1,34% QUEBEC GRANBY (LA HAUTE-YAMASKA) LA VOIX DE L'EST MON-FRI 14 951 15 483 -3,44% QUEBEC MONTREAL (COMMUNAUTE-URBAINE -DE-MONTREAL)GAZETTE AVG (M-F) 147 668 143 782 2,70% QUEBEC MONTREAL (COMMUNAUTE-URBAINE- DE-MONTREAL)LE DEVOIR AVG (M-F) 26 099 26 181 -0,31% QUEBEC MONTREAL (COMMUNAUTE-URBAINE- DE-MONTREAL)LA PRESSE AVG (M-F) 198 306 200 049 -0,87% QUEBEC QUEBEC (COMMUNAUTE- URBAINE-DE-QUEBEC) LE SOLEIL AVG (M-F) 77 032 81 724 -5,74% QUEBEC SHERBROOKE (SHERBROOKE CO.) LA TRIBUNE AVG (M-F) 31 617 32 006 -1,22% QUEBEC SHERBROOKE (SHERBROOKE CO.) RECORD MON-FRI 4 367 4 539 -3,79% QUEBEC TROIS-RIVIERES (FRANCHEVILLE CEN. DIV. (MRC) LE NOUVELLISTE AVG (M-F) 41 976 41 886 0,21% ONTARIO OTTAWA CITIZEN AVG (M-F) 118 373 124 654 -5,04% ONTARIO OTTAWA-HULL LE DROIT AVG (M-F) 35 146 34 538 1,76% ONTARIO THUNDER BAY (THUNDER BAY DIST.) CHRONICLE-JOURNAL AVG (M-F) 25 495 26 112 -2,36% ONTARIO TORONTO GLOBE AND MAIL AVG (M-F) 301 820 329 504 -8,40% ONTARIO TORONTO NATIONAL POST AVG (M-F) 150 884 190 187 -20,67% ONTARIO WINDSOR (ESSEX CO.) STAR AVG (M-F) 61 028 66 080 -7,65% MANITOBA BRANDON (CEN. -

Prescribed by Law/Une Règle De Droit©

PRESCRIBED BY LAW/UNE RÈGLE © DE DROIT ∗ ROBERT LECKEY In Multani, the Supreme Court of Canada’s Dans l’affaire Multani sur le port du kirpan, les kirpan case, judges disagree over the proper juges de la Cour suprême du Canada exprimèrent approach to reviewing administrative action under leur désaccord au sujet de l’approche adéquate au the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The contrôle des décisions administratives en vertu de la concurring judges questioned the leading judgment, Charte canadienne des droits et libertés. Les juges Slaight Communications, on the basis that it is minoritaires remirent en question l’arrêt Slaight inconsistent with the French text of section 1. This Communications, arguant que ce précédent était disagreement stimulates reflections on language and incompatible avec la version française de l’article culture in Canadian constitutional and administrative premier de la Charte. Ce désaccord soulève des law. A reading of both language versions of section 1, réflexions au sujet du rôle du langage et de la culture Slaight, and the critical scholarship reveals a au sein du droit constitutionnel et administratif linguistic dualism in which scholars read one version canadien. Une lecture des versions anglaise et of the Charter and of the judgment and write about française de l’article premier et de Slaight et de la them in that language. The separate streams doctrine revèle un dualisme linguistique par lequel undermine the idea of a shared, bilingual public law. les juristes lisent une seule version de la Charte et du Yet the differences exceed language. The article jugement et les commentent en cette même langue. -

Canada Questions and Answers for NCSEA International Subcommittee

NCSEA International Sub-committee conference call presentation - notes Dec. 17, 2019 QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS: CANADA 1. Can you provide any update as to when Canada is likely to ratify the 2007 Hague Convention? The following steps are still required before Canada can ratify the 2007 Convention: 1) Finalize the draft uniform act for the implementation of the 2007 Convention by interested Canadian provinces and territories; 2) Adoption of the uniform act by some provinces and territories; and 3) Finally, ratification of the Convention and extension to those provinces or territories that have adopted legislation and want the Convention to apply in their territory. 2. When the Convention comes into force, we understand that it may not necessarily apply to all provinces and territories. How will cases where a parent leaves a Convention province and goes to a non-Convention province be handled? Where a parent leaves a Convention province and goes to a non-Convention province, the file can be transferred to the non-Convention province for processing only if the requesting State has a reciprocity arrangement with the non-Convention province. If no reciprocity arrangement exists between the non-Convention province and the requesting State, then the applicant will need to obtain private counsel in Canada to assist them with their case. 3. REMO has recently had correspondence returned from the following address : Family Responsibility Office, Interjurisdictional Support Orders Unit, PO Box 600, Steeles West Post Office, Toronto, Ontario, M3J OK8, Canada-cover envelope suggests the office has moved. Can you confirm where REMO should write instead please? Ontario confirms this is the correct address. -

Sherbrooke : Sa Place Dans La Vie De Relations Des Cantons De L’Est Pierre Cazalis

Document généré le 1 oct. 2021 05:11 Cahiers de géographie du Québec Sherbrooke : sa place dans la vie de relations des Cantons de l’Est Pierre Cazalis Volume 8, numéro 16, 1964 Résumé de l'article Because they are due to economic contingencies rather than to unfavourable URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/020498ar natural conditions, present-day regional disparities compel the geographer to DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/020498ar modify his concept of the region. Whereas in the past the region was considered essentially as a physical entity, to many authors it appears today to Aller au sommaire du numéro be « a functional area, based on communication and exchange, and as such defined less by its limits than by its centre » (Juillard). It is this concept which will be used in regional planning. Éditeur(s) Taking the city of Sherbrooke as a nodal centre, the author attempts to define such a region through an analysis and graphical representation of the Département de géographie de l'Université Laval complementary roles in influence and attraction played by the city in the fundamental aspects of employment, trade, finance, education, ISSN communication, health and government. Although it is already well-developed in the secondary sector, with more than 9,000 workers employed in industry 0007-9766 (imprimé) and an annual production worth more than $100 million, Sherbrooke bas a 1708-8968 (numérique) power of attraction and influence which is due essentially to its tertiary sector : wholesale trade, insurance, education, communication. Ac-cording to the Découvrir la revue criteria mentioned above, the area dominated by Sherbrooke includes the whole of the following counties : Sherbrooke, Stanstead, Richmond, Wolfe and Compton ; and the greater part of Frontenac, Mégantic, Artbabaska, Citer cet article Drummond and Brome counties. -

030140236.Pdf

UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC MÉMOIRE PRÉSENTÉ À L'UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À TROIS-RIVIÈRES COMME EXIGENCE PARTIELLE DE LA MAÎTRISE EN ÉTUDES QUÉBÉCOISES PAR CATHERINE LAMPRON-DESAULNIERS LA VIE CULTURELLE À TROIS-RIVIÈRES DANS LES ANNÉES 1960 : DÉMOCRATISA TI ON DE LA CUL TURE, DÉMOCRATIE CUL TU REL LE ET CUL TURE JEUNE. HISTOIRE D'UNE TRANSITION MARS 2010 Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières Service de la bibliothèque Avertissement L’auteur de ce mémoire ou de cette thèse a autorisé l’Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières à diffuser, à des fins non lucratives, une copie de son mémoire ou de sa thèse. Cette diffusion n’entraîne pas une renonciation de la part de l’auteur à ses droits de propriété intellectuelle, incluant le droit d’auteur, sur ce mémoire ou cette thèse. Notamment, la reproduction ou la publication de la totalité ou d’une partie importante de ce mémoire ou de cette thèse requiert son autorisation. RÉSUMÉ L'objectif principal de cette recherche vise à mettre en lumière la transition culturelle qui s'effectue à Trois-Rivières au cours des années 1960. Le milieu culturel se transforme à plusieurs niveaux: les lieux de diffusion culturelle, les acteurs ainsi que la programmation culturelle en sont des exemples. L'analyse démontre tout le processus de démocratisation de la culture cultivée pris en charge par l'élite ainsi que l'émergence, à la fin de la décennie, de la démocratie culturelle mise de l'avant par une jeunesse qui sait s'imposer. Ces deux groupes ont su démontrer les caractéristiques dominantes de la diffusion de la culture cultivée dans une ville moyenne comme Trois-Rivières. -

Short Essay on the Notion of General Interest in Article 982 of the Civil Code of Québec Or Je Puise Mais N’Épuise ∗

SHORT ESSAY ON THE NOTION OF GENERAL INTEREST IN ARTICLE 982 OF THE CIVIL CODE OF QUÉBEC OR JE PUISE MAIS N’ÉPUISE ∗ Robert P. Godin † There is a beautiful stained glass window located in the library of the National Assembly of Québec showing a young person drawing water from a stream, that has a most appropriate title referring in a very subtle way to the fact that all the knowledge and information contained in the library is easily accessible and can be drawn upon without impairing its existence: “Je puise mais n’épuise ,” a literal translation of which could be “I do not deplete the source I draw upon.” The concept expressed in this image is appropriate to the many aspects of the current discourse with respect to water resources. It also serves to better illustrate the Legislature’s intention in qualifying the import of Article 982 of the Civil Code of Québec (C.C.Q.) with the notion of general interest . ∗ Editor’s Note: Citations herein generally conform to THE BLUEBOOK : A UNIFORM SYSTEM OF CITATION (Columbia Law Review Ass’n et al. eds., 18th ed. 2005). In order to make the citations more useful for Canadian practitioners, abbreviations and certain other conventions have been adopted from the CANADIAN GUIDE TO UNIFORM LEGAL CITATION [Manuel Canadien de la Référence Juridique] (McGill Law Journal eds., 4th ed. [Revue du droit de McGill, 4e éd.] 1998). † Professor Robert P. Godin is an Adjunct Professor at the Faculty of Law, McGill University, Montreal, Canada. He was appointed Senior Wainwright Fellow. This Article is the text of the author’s presentation at the Workshop on Water held at the Vermont Law School on October 24, 2009. -

The Hidden Ally: How the Canadian Supreme Court Has Advanced the Vitality of the Francophone Quebec Community

The Hidden Ally: How the Canadian Supreme Court Has Advanced the Vitality of the Francophone Québec Community DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Douglas S. Roberts, B.A., J.D., M.A. Graduate Program in French and Italian The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Professor Wynne Wong, Advisor Professor Danielle Marx-Scouras, Advisor Professor Jennifer Willging Copyright by Douglas S. Roberts 2015 Abstract Since the adoption of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1982, the Canadian Supreme Court has become a much more powerful and influential player in the Canadian political and social landscape. As such, the Court has struck down certain sections of the Charter of the French Language (Bill 101) as contrary to the Constitution, 1867 and the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. In Ford v. Québec, [1988] 2 S.C.R. 712, for instance, the Court found unconstitutional that portion of Bill 101 that required commercial signage to be in French only. After the decision was announced, public riots broke out in Montreal. As a result of this decision, one could conclude that the Court has, in fact, resisted Québec‘s attempts to protect and promote its own language and culture. In this dissertation, however, I argue that this perception is not justified, primarily because it fails to recognize how Canadian federalism protects diversity within the Confederation. Contrary to the initial public reaction to the Ford case, my contention is that the Court has, in fact, advanced and protected the vitality of Francophone Québec by developing three fundamental principles. -

Directors' Report to Shareholders

Directors’ Report to Shareholders The Power Corporation family of companies and investments had a very strong year in 2011, with stable results from the financial services businesses and a meaningful contribution from investing activities. While 2011 showed continued progress in global economic recovery, the year was nonetheless challenging. Interest rates were low and the economy and equity markets showed progress during the first half. This largely reversed itself during the second half of the year. Our results indicate that we have the risk-management culture, capital and liquidity to navigate these economic conditions successfully and that investment gains represent an attractive upside to our business. 2011 $499.6 $1,152 $574 BILLION MILLION MILLION CONSOLIDATED OPERATING DIVIDENDS ASSETS AND EARNINGS DECLARED ASSETS UNDER ATTRIBUTABLE TO MANAGEMENT PARTICIPATING SHAREHOLDERS Mission 13.0% $2.50 $1.16 Enhancing shareholder value RETURN ON OPERATING DIVIDENDS by actively managing operating EQUITY EARNINGS DECLARED BASED ON PER PER businesses and investments which OPERATING PARTICIPATING PARTICIPATING EARNINGS SHARE SHARE can generate long-term, sustainable growth in earnings and dividends. Value is best achieved through a prudent approach to risk and through responsible corporate citizenship. Power Corporation aims to act like an owner with a long-term perspective and a strategic vision anchored in strong core values. 6 POWER CORPORATION OF CANADA 2011 ANNUAL REPORT Power Corporation’s financial services companies are focused on providing protection, asset management, and retirement savings products and services. We continue to believe that the demographic trends affecting retirement savings, coupled with strong evidence that advice from a qualified financial advisor creates added value for our clients, reinforce the soundness of our strategy of building an advice-based multi-channel distribution platform in North America. -

2021 Ownership Groups - Canadian Daily Newspapers (74 Papers)

2021 Ownership Groups - Canadian Daily Newspapers (74 papers) ALTA Newspaper Group/Glacier (3) CN2i (6) Independent (6) Quebecor (2) Lethbridge Herald # Le Nouvelliste, Trois-Rivieres^^ Prince Albert Daily Herald Le Journal de Montréal # Medicine Hat News # La Tribune, Sherbrooke^^ Epoch Times, Vancouver Le Journal de Québec # The Record, Sherbrooke La Voix de l’Est, Granby^^ Epoch Times, Toronto Le Soleil, Quebec^^ Le Devoir, Montreal Black Press (2) Le Quotidien, Chicoutimi^^ La Presse, Montreal^ SaltWire Network Inc. (4) Red Deer Advocate Le Droit, Ottawa/Gatineau^^ L’Acadie Nouvelle, Caraquet Cape Breton Post # Vancouver Island Free Daily^ Chronicle-Herald, Halifax # The Telegram, St. John’s # Brunswick News Inc. (3) The Guardian, Charlottetown # Times & Transcript, Moncton # Postmedia Network Inc./Sun Media (33) The Daily Gleaner, Fredericton # National Post # The London Free Press Torstar Corp. (7) The Telegraph-Journal, Saint John # The Vancouver Sun # The North Bay Nugget Toronto Star # The Province, Vancouver # Ottawa Citizen # The Hamilton Spectator Continental Newspapers Canada Ltd.(3) Calgary Herald # The Ottawa Sun # Niagara Falls Review Penticton Herald The Calgary Sun # The Sun Times, Owen Sound The Peterborough Examiner The Daily Courier, Kelowna Edmonton Journal # St. Thomas Times-Journal St. Catharines Standard The Chronicle Journal, Thunder Bay The Edmonton Sun # The Observer, Sarnia The Tribune, Welland Daily Herald-Tribune, Grande Prairie The Sault Star, Sault Ste Marie The Record, Grand River Valley F.P. Canadian Newspapers LP (2) The Leader-Post, Regina # The Simcoe Reformer Winnipeg Free Press The StarPhoenix, Saskatoon # Beacon-Herald, Stratford TransMet (1) Brandon Sun Winnipeg Sun # The Sudbury Star Métro Montréal The Intelligencer, Belleville The Daily Press, Timmins Glacier Media (1) The Expositor, Brantford The Toronto Sun # Times Colonist, Victoria # The Brockville Recorder & Times The Windsor Star # The Chatham Daily News The Sentinel Review, Woodstock Globe and Mail Inc.