For the Good of Franco-Ontarians: Le Droit's Editorials, 1913-1933 Mario R. Gravelle a Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty O

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ishaq V Canada: “Social Science Facts” in Feminist Interventions Dana Phillips

Document generated on 09/25/2021 1:10 p.m. Windsor Yearbook of Access to Justice Recueil annuel de Windsor d'accès à la justice Ishaq v Canada: “Social Science Facts” in Feminist Interventions Dana Phillips Volume 35, 2018 Article abstract This article examines the role of social science in feminist intervener advocacy, URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1057069ar focusing on the 2015 case ofIshaq v Canada (Minister of Citizenship and DOI: https://doi.org/10.22329/wyaj.v35i0.5271 Immigration). InIshaq, a Muslim woman challenged a Canadian government policy requiring her to remove her niqab while reciting the citizenship oath. See table of contents The Federal Court of Appeal dismissed several motions for intervention by feminist and other equality-seeking organizations, emphasizing their improper reliance on unproven social facts and social science research. I argue that this Publisher(s) decision departs from the generous approach to public interest interventions sanctioned by the federal and other Canadian courts. More importantly, the Faculty of Law, University of Windsor Court’s characterization of the intervener submissions as relying on “social science facts” that must be established through the evidentiary record ISSN diminishes the capacity of feminist interveners to effectively support equality and access to justice for marginalized groups in practice. 2561-5017 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Phillips, D. (2018). Ishaq v Canada: “Social Science Facts” in Feminist Interventions. Windsor Yearbook of Access to Justice / Recueil annuel de Windsor d'accès à la justice, 35, 99–126. https://doi.org/10.22329/wyaj.v35i0.5271 Copyright (c), 2019 Dana Phillips This document is protected by copyright law. -

Canada East Equipment Dealers' Association (CEEDA)

Industry Update from Canada: Canada East Equipment Dealers' Association (CEEDA) Monday, 6 July 2020 In partnership with Welcome Michael Barton Regional Director, Canada Invest Northern Ireland – Americas For up to date information on Invest Northern Ireland in the Americas, follow us on LinkedIn & Twitter. Invest Northern Ireland – Americas @InvestNI_USA 2 Invest Northern Ireland – Americas: Export Continuity Support in the Face of COVID-19 Industry Interruption For the Canadian Agri-tech sector… Industry Updates Sessions with industry experts to provide Northern Ireland manufacturers with updates on the Americas markets to assist with export planning and preparation Today’s Update We are delighted to welcome Beverly Leavitt, President & CEO of the Canada East Equipment Dealers' Association (CEEDA). CEEDA represents Equipment Dealers in the Province of Ontario, and the Atlantic Provinces in the Canadian Maritimes. 3 Invest Northern Ireland – Americas: Export Continuity Support in the Face of COVID-19 Industry Interruption For the Canadian Agri-tech sector… Virtual Meet-the-Buyer programs designed to provide 1:1 support to connect Northern Ireland manufacturers with potential Canadian equipment dealers Ongoing dealer development in Eastern & Western Canada For new-to-market exporters, provide support, industry information and routes to market For existing exporters, market expansion and exploration of new Provinces 4 Invest Northern Ireland – Americas: Export Continuity Support in the Face of COVID-19 Industry Interruption For the Canadian -

From European Contact to Canadian Independence

From European Contact to Canadian Independence Standards SS6H4 The student will describe the impact of European contact on Canada. a. Describe the influence of the French and the English on the language and religion of Canada. b. Explain how Canada became an independent nation. From European Contact to Quebec’s Independence Movement • The First Nations are the native peoples of Canada. • They came from Asia over 12,000 years ago. • They crossed the Bering Land Bridge that joined Russia to Alaska. • There were 12 tribes that made up the First Nations. • The Inuit are one of the First Nation tribes. • They still live in Canada today. • In 1999, Canada’s government gave the Inuit Nunavut Territory in northeast Canada. • The first explorers to settle Canada were Norse invaders from the Scandinavian Peninsula. • In 1000 CE, they built a town on the northeast coast of Canada and established a trading relationship with the Inuit. • The Norse deserted the settlement for unknown reasons. • Europeans did not return to Canada until almost 500 years later… • The Italian explorer, John Cabot, sailed to Canada’s east coast in 1497. • Cabot claimed an area of land for England (his sponsor) and named it “Newfoundland”. •Jacques Cartier sailed up the St. Lawrence River in 1534. •He claimed the land for France. •French colonists named the area “New France”. • In 1608, Samuel de Champlain built the first permanent French settlement in New France— called Quebec. • The population grew slowly. • Many people moved inland to trap animals. • Hats made of beaver fur were in high demand in Europe. -

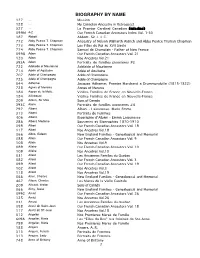

Biography by Name 127

BIOGRAPHY BY NAME 127 ... Missing 128 ... My Canadian Ancestry in Retrospect 327 ... Le Premier Cardinal Canadien (missing) 099M A-Z Our French Canadian Ancestors Index Vol. 1-30 187 Abbott Abbott, Sir J. J. C. 772 Abby Pearce T. Chapman Ancestry of Nelson Wilmarth Aldrich and Abby Pearce Truman Chapman 773 Abby Pearce T. Chapman Les Filles du Roi au XVII Siecle 774 Abby Pearce T. Chapman Samuel de Champlain - Father of New France 099B Adam Our French Canadian Ancestors Vol. 21 120 Adam Nos Ancetres Vol.21 393A Adam Portraits de familles pionnieres #2 722 Adelaide of Maurienne Adelaide of Maurienne 714 Adele of Aquitaine Adele of Aquitaine 707 Adele of Champagne Adele of Champagne 725 Adele of Champagne Adele of Champagne 044 Adhemar Jacques Adhemar, Premier Marchand a Drummondville (1815-1822) 728 Agnes of Merania Agnes of Merania 184 Aigron de la Motte Vieilles Familles de France en Nouvelle-France 184 Ailleboust Vieilles Familles de France en Nouvelle-France 209 Aitken, Sir Max Sons of Canada 393C Alarie Portraits de familles pionnieres #4 292 Albani Albani - Lajeunesse, Marie Emma 313 Albani Portraits de Femmes 406 Albani Biographie d'Albani - Emma Lajeunesse 286 Albani, Madame Souvenirs et Biographies 1870-1910 098 Albert Our French Canadian Ancestors Vol. 18 117 Albert Nos Ancetres Vol.18 066 Albro, Gideon New England Families - Genealogical and Memorial 088 Allain Our French Canadian Ancestors Vol. 9 108 Allain Nos Ancetres Vol.9 089 Allaire Our French Canadian Ancestors Vol. 10 109 Allaire Nos Ancetres Vol.10 031 Allard Les Anciennes Familles du Quebec 082 Allard Our French Canadian Ancestors Vol. -

Language Guarantees and the Power to Amend the Canadian Constitution

Language Guarantees and the Power to Amend the Canadian Constitution Armand L. C. de Mestral and William Fraiberg * Introduction An official language may be defined as one ordained by law to be used in the public institutions of a state; more particularly in its legislature and laws, its courts, its public administration and its public schools.1 In Canada, while language rights have historically been an issue of controversy, only a partial provision for official languages as above defined is to be found in the basic constitutional Acts. The British North America Act, in sec. 133,2 gives limited re- cognition to both Engish and French in the courts, laws, and legis- latures of Canada and Quebec. With the possible exception of Quebec, the Provinces would appear to have virtually unlimited freedom to legislate with respect to language in all spheres of public activity within their jurisdiction. English is the "official" language of Mani- toba by statute 3 and is the language of the courts of Ontario.4 While Alberta and Saskatchewan have regu'ated the language of their schools,5 they have not done so with respect to their courts and • Of the Editorial Board, McGill Law Journal; lately third law students. 'The distinction between an official language and that used in private dis- course is clearly drawn by the Belgian Constitution: Art. 23. "The use of the language spoken in Belgium is optional. This matter may be regulated only by law and only for acts of public authority and for judicial proceedings." Peaslee, A. J., Constitutions of Nations, Concord, Rumford Press, 1950, p. -

OTT !~ LEI 7Une/Futy 1995 ,-Dedicated to `Preserving Our Budt .Heritage

Estabtished in x967 Votume 22, No . x, HERITAGE r~ Celebrating our 20 year ~OTT !~ LEI 7une/futy 1995 ,-Dedicated to `Preserving Our Budt .Heritage Heritage Ottawa's New President Membership Alert! by Louise Goatee Call it summer malaise, call it mailbox Dear Heritage Activist, years. It has been great fun to set up an overload . What ever the reason, "Interiors Symposium", stage lectures on Heritage Ottawa's membership rolls I would like to inform you that Heritage preservation, help organize the auction of need rejuvenating! If each recipient of Ottawa has a new president! this newsletter introduced ONE NEW architectural drawings, gather members to MEMBER, we would meet the obliga- Jennifer Rosebrugh has been a member of rally and share ideas with others on the tions of our (shoe-string) 1995 budget Heritage Ottawa for years and has recently future of our past . I have met a great many and continue the fight to protect working abroad . She who share the passion to save, care returned home from people Ottawa's built heritage. Can you help Canada's historical is very interested in the conservation of for and make use of spread the word? Friends, neighbours, heritage architecture and has already architecture . While there are many fasci- colleagues... We need YOUR assistance. proved to be a willing and capable mem- nating aspects to the heritage field, I feel Annual dues are $15 .00 (student/senior), ber of the heritage community. Jennifer Heritage Ottawa's primary role is still to $20 .00 for individuals, $25 .00 for a fami- was one of the stronger voices who man- prevent any further demolition of our older ly and $50 .00 for a patron membership . -

Downloaded from the Historica 8E79-6Cf049291510)

Petroglyphs in Writing-On- “Language has always LANGUAGE POLICY & Stone Provincial 1774 Park, Alberta, The Quebec Act is passed by the British parliament. To Message been, and remains, RELATIONS IN CANADA: (Dreamstime.com/ TIMELINE Photawa/12622594). maintain the support of the French-speaking majority to Teachers at the heart of the in Québec, the act preserves freedom of religion and canadian experience.” reinstates French civil law. Demands from the English This guide is an introduction to the Official Languages Graham Fraser, minority that only English-speaking Protestants could Act and the history of language policy in Canada, and Time immemorial vote or hold office are rejected. former Commissioner is not exhaustive in its coverage. The guide focuses An estimated 300 to 450 languages are spoken of Official Languages primarily on the Act itself, the factors that led to its Flags of Québec and La Francophonie, 2018 by Indigenous peoples living in what will become (2006-2016) (Dreamstime.com/Jerome Cid/142899004). creation, and its impact and legacy. It touches on key modern Canada. The Mitred Minuet (courtesy moments in the history of linguistic policy in Canada, Library and though teachers may wish to address topics covered 1497 Archives inguistic plurality is a cornerstone of modern Canadian identity, but the history of language in Canada/ e011156641). in Section 1 in greater detail to provide a deeper Canada is not a simple story. Today, English and French enjoy equal status in Canada, although John Cabot lands somewhere in Newfoundland or understanding of the complex nature of language Lthis has not always been the case. -

Language Planning and Education of Adult Immigrants in Canada

London Review of Education DOI:10.18546/LRE.14.2.10 Volume14,Number2,September2016 Language planning and education of adult immigrants in Canada: Contrasting the provinces of Quebec and British Columbia, and the cities of Montreal and Vancouver CatherineEllyson Bem & Co. CarolineAndrewandRichardClément* University of Ottawa Combiningpolicyanalysiswithlanguagepolicyandplanninganalysis,ourarticlecomparatively assessestwomodelsofadultimmigrants’languageeducationintwoverydifferentprovinces ofthesamefederalcountry.Inordertodoso,wefocusspecificallyontwoquestions:‘Whydo governmentsprovidelanguageeducationtoadults?’and‘Howisitprovidedintheconcrete settingoftwoofthebiggestcitiesinCanada?’Beyonddescribingthetwomodelsofadult immigrants’ language education in Quebec, British Columbia, and their respective largest cities,ourarticleponderswhetherandinwhatsensedemography,languagehistory,andthe commonfederalframeworkcanexplainthesimilaritiesanddifferencesbetweenthetwo.These contextualelementscanexplainwhycitiescontinuetohavesofewresponsibilitiesregarding thesettlement,integration,andlanguageeducationofnewcomers.Onlysuchunderstandingwill eventuallyallowforproperreformsintermsofcities’responsibilitiesregardingimmigration. Keywords: multilingualcities;multiculturalism;adulteducation;immigration;languagelaws Introduction Canada is a very large country with much variation between provinces and cities in many dimensions.Onesuchaspect,whichremainsacurrenthottopicfordemographicandhistorical reasons,islanguage;morespecifically,whyandhowlanguageplanningandpolicyareenacted -

Brief Regarding the Future of Regional News Submitted to The

Brief Regarding the Future of Regional News Submitted to the Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage By The Fédération nationale des communications – CSN April 18, 2016 Contents Contents ............................................................................................................................................................................ 3 Foreword .......................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................... 5 The role of the media in our society ..................................................................................................................... 7 The informative role of the media ......................................................................................................................... 7 The cultural role of the media ................................................................................................................................. 7 The news: a public asset ............................................................................................................................................ 8 Recent changes to Quebec’s media landscape .................................................................................................. 9 Print newspapers .................................................................................................................................................... -

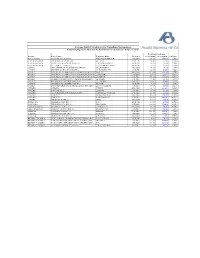

Average Daily Circulation for Canadian Newspapers Preliminary Figures As Filed with the Audit Bureau of Circulations -- Subject to Audit

Average Daily Circulation for Canadian Newspapers Preliminary Figures as Filed with the Audit Bureau of Circulations -- Subject to Audit Total Paid Circulation Province City (County) Newspaper Name Frequency As of 9/30/09 As of 9/30/08 % Change NOVA SCOTIA HALIFAX (HALIFAX CO.) CHRONICLE-HERALD AVG (M-F) 108 182 110 875 -2,43% NEW BRUNSWICK FREDERICTON (YORK CO.) GLEANER MON-FRI 20 863 21 553 -3,20% NEW BRUNSWICK MONCTON (WESTMORLAND CO.) TIMES-TRANSCRIPT MON-FRI 36 115 36 656 -1,48% NEW BRUNSWICK ST. JOHN (ST. JOHN CO.) TELEGRAPH-JOURNAL MON-FRI 32 574 32 946 -1,13% QUEBEC CHICOUTIMI (LE FJORD-DU-SAGUENAY) LE QUOTIDIEN AVG (M-F) 26 635 26 996 -1,34% QUEBEC GRANBY (LA HAUTE-YAMASKA) LA VOIX DE L'EST MON-FRI 14 951 15 483 -3,44% QUEBEC MONTREAL (COMMUNAUTE-URBAINE -DE-MONTREAL)GAZETTE AVG (M-F) 147 668 143 782 2,70% QUEBEC MONTREAL (COMMUNAUTE-URBAINE- DE-MONTREAL)LE DEVOIR AVG (M-F) 26 099 26 181 -0,31% QUEBEC MONTREAL (COMMUNAUTE-URBAINE- DE-MONTREAL)LA PRESSE AVG (M-F) 198 306 200 049 -0,87% QUEBEC QUEBEC (COMMUNAUTE- URBAINE-DE-QUEBEC) LE SOLEIL AVG (M-F) 77 032 81 724 -5,74% QUEBEC SHERBROOKE (SHERBROOKE CO.) LA TRIBUNE AVG (M-F) 31 617 32 006 -1,22% QUEBEC SHERBROOKE (SHERBROOKE CO.) RECORD MON-FRI 4 367 4 539 -3,79% QUEBEC TROIS-RIVIERES (FRANCHEVILLE CEN. DIV. (MRC) LE NOUVELLISTE AVG (M-F) 41 976 41 886 0,21% ONTARIO OTTAWA CITIZEN AVG (M-F) 118 373 124 654 -5,04% ONTARIO OTTAWA-HULL LE DROIT AVG (M-F) 35 146 34 538 1,76% ONTARIO THUNDER BAY (THUNDER BAY DIST.) CHRONICLE-JOURNAL AVG (M-F) 25 495 26 112 -2,36% ONTARIO TORONTO GLOBE AND MAIL AVG (M-F) 301 820 329 504 -8,40% ONTARIO TORONTO NATIONAL POST AVG (M-F) 150 884 190 187 -20,67% ONTARIO WINDSOR (ESSEX CO.) STAR AVG (M-F) 61 028 66 080 -7,65% MANITOBA BRANDON (CEN. -

Prescribed by Law/Une Règle De Droit©

PRESCRIBED BY LAW/UNE RÈGLE © DE DROIT ∗ ROBERT LECKEY In Multani, the Supreme Court of Canada’s Dans l’affaire Multani sur le port du kirpan, les kirpan case, judges disagree over the proper juges de la Cour suprême du Canada exprimèrent approach to reviewing administrative action under leur désaccord au sujet de l’approche adéquate au the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The contrôle des décisions administratives en vertu de la concurring judges questioned the leading judgment, Charte canadienne des droits et libertés. Les juges Slaight Communications, on the basis that it is minoritaires remirent en question l’arrêt Slaight inconsistent with the French text of section 1. This Communications, arguant que ce précédent était disagreement stimulates reflections on language and incompatible avec la version française de l’article culture in Canadian constitutional and administrative premier de la Charte. Ce désaccord soulève des law. A reading of both language versions of section 1, réflexions au sujet du rôle du langage et de la culture Slaight, and the critical scholarship reveals a au sein du droit constitutionnel et administratif linguistic dualism in which scholars read one version canadien. Une lecture des versions anglaise et of the Charter and of the judgment and write about française de l’article premier et de Slaight et de la them in that language. The separate streams doctrine revèle un dualisme linguistique par lequel undermine the idea of a shared, bilingual public law. les juristes lisent une seule version de la Charte et du Yet the differences exceed language. The article jugement et les commentent en cette même langue. -

Sherbrooke : Sa Place Dans La Vie De Relations Des Cantons De L’Est Pierre Cazalis

Document généré le 1 oct. 2021 05:11 Cahiers de géographie du Québec Sherbrooke : sa place dans la vie de relations des Cantons de l’Est Pierre Cazalis Volume 8, numéro 16, 1964 Résumé de l'article Because they are due to economic contingencies rather than to unfavourable URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/020498ar natural conditions, present-day regional disparities compel the geographer to DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/020498ar modify his concept of the region. Whereas in the past the region was considered essentially as a physical entity, to many authors it appears today to Aller au sommaire du numéro be « a functional area, based on communication and exchange, and as such defined less by its limits than by its centre » (Juillard). It is this concept which will be used in regional planning. Éditeur(s) Taking the city of Sherbrooke as a nodal centre, the author attempts to define such a region through an analysis and graphical representation of the Département de géographie de l'Université Laval complementary roles in influence and attraction played by the city in the fundamental aspects of employment, trade, finance, education, ISSN communication, health and government. Although it is already well-developed in the secondary sector, with more than 9,000 workers employed in industry 0007-9766 (imprimé) and an annual production worth more than $100 million, Sherbrooke bas a 1708-8968 (numérique) power of attraction and influence which is due essentially to its tertiary sector : wholesale trade, insurance, education, communication. Ac-cording to the Découvrir la revue criteria mentioned above, the area dominated by Sherbrooke includes the whole of the following counties : Sherbrooke, Stanstead, Richmond, Wolfe and Compton ; and the greater part of Frontenac, Mégantic, Artbabaska, Citer cet article Drummond and Brome counties.