Download Here

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography

Bibliography Archival Sources Ars¸ivi, Bas¸bakanlık Osmanlı (BOA) FO 195/237; 1841 FO 248/114 India Offi ce G/29/27. In Arabic Afghani, Ahmad al-. Sarab fi Iran: Kalima Sari‘a hawla al-Khumayni wa-Din al-Shi‘a, n.p., 1982. ‘Alawi, Hasan al-. Al-Shi‘a wal-Dawla al-Qawmiyya fi al-‘Iraq 1914–1990, n.p., 1990. Alusi, Shukri al-. al-Misk al-Adhfar, Baghdad: al-Maktaba al-‘Arabiyya, 1930. Alusi, Shihab al-Din Mahmud al-. Al-Tibyan fi Sharh al-Burhan, 1249/1833. Amin, Muhsin al-. A‘yan al-Shi‘a, Sidon, vol. 40, 1957. Bahr al-‘Ulum, Muhammad Sadiq. “Muqaddima,” in Muhammad Mahdi b. Murtada Tabataba’i, Rijal al-Sayyid Bahr al-‘Ulum al-Ma‘ruf bil-Fawa’id al-Rijaliyya, Najaf: n.p, 1967. Din, Muhammad Hirz al-. Ma ‘arif al-Rijal fi Tarajim al-‘Ulama’ wal-Udaba’, Najaf, vol. 1, 1964–1965. Dujayli, Ja‘far (ed.). Mawsu‘at al-Najaf al-Ashraf, Beirut: Dar al-Adwa’, 1993. Fahs, Hani. Al-Shi‘a wal-Dawla fi Lubnan: Malamih fi al-Ru’ya wal-Dhakira, Beirut: Dar al-Andalus, 1996. Hamdani al-. Takmilat Ta’rikh al-Tabari, Beirut: al-Matba‘at al-Kathulikiyya, 1961. Hawwa, Sa‘id. Al-Islam, Beirut: Dar al-Kutub, 1969. ———. Al-Khumayniyya: Shudhudh fi al-‘Aqa’id Shudhudh fi al-Mawaqif, Beirut: Dar ‘Umar, 1987. ———. Hadhihi Tajribati wa-Hadhihi Shahadati, Beirut: Dar ‘Umar, 1988. Husri, Sati‘ al-. Mudhakkirati fi al-‘Iraq, 1921–1941, Beirut: Manshurat dar al- Tali‘a, 1967. Ibn Abi Ya‘la. Tabaqat al-Hanabila, Cairo: Matba‘at al-Sunna al-Muhammadiyya, 1952. -

“A Translation and Historical Commentary of Book One and Book Two of the Historia of Geōrgios Pachymerēs” 2004

“A Translation and Historical Commentary of Book One and Book Two of the Historia of Geōrgios Pachymerēs” Nathan John Cassidy, BA(Hons) (Canterbury) This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Western Australia. School of Humanities Classics and Ancient History 2004 ii iii Abstract A summary of what a historical commentary should aim to do is provided by Gomme and Walbank in the introductions to their famous and magisterial commentaries on Thoukydidēs and Polybios. From Gomme: A historical commentary on an historian must necessarily derive from two sources, a proper understanding of his own words, and what we can learn from other authorities . To see what gaps there are in his narrative [and to] examine the means of filling these gaps. (A. Gomme A Historical Commentary on Thucydides vol. 1 (London, 1959) 1) And from Walbank: I have tried to give full references to other relevant ancient authorities, and where the text raises problems, to define these, even if they could not always be solved. Primarily my concern has been with whatever might help elucidate what Polybius thought and said, and only secondarily with the language in which he said it, and the question whether others subsequently said something identical or similar. (F. Walbank A Historical Commentary on Polybius vol. 1 (London, 1957) vii) Both scholars go on to stress the need for the commentator to stick with the points raised by the text and to avoid the temptation to turn the commentary into a rival narrative. These are the principles which I have endeavoured to follow in my Historical Commentary on Books One and Two of Pachymerēs’ Historia. -

Phd 15.04.27 Versie 3

Promotor Prof. dr. Jan Dumolyn Vakgroep Geschiedenis Decaan Prof. dr. Marc Boone Rector Prof. dr. Anne De Paepe Nederlandse vertaling: Een Spiegel voor de Sultan. Staatsideologie in de Vroeg Osmaanse Kronieken, 1300-1453 Kaftinformatie: Miniature of Sultan Orhan Gazi in conversation with the scholar Molla Alâeddin. In: the Şakayıku’n-Nu’mâniyye, by Taşköprülüzâde. Source: Topkapı Palace Museum, H1263, folio 12b. Faculteit Letteren & Wijsbegeerte Hilmi Kaçar A Mirror for the Sultan State Ideology in the Early Ottoman Chronicles, 1300- 1453 Proefschrift voorgelegd tot het behalen van de graad van Doctor in de Geschiedenis 2015 Acknowledgements This PhD thesis is a dream come true for me. Ottoman history is not only the field of my research. It became a passion. I am indebted to Prof. Dr. Jan Dumolyn, my supervisor, who has given me the opportunity to take on this extremely interesting journey. And not only that. He has also given me moral support and methodological guidance throughout the whole process. The frequent meetings to discuss the thesis were at times somewhat like a wrestling match, but they have always been inspiring and stimulating. I also want to thank Prof. Dr. Suraiya Faroqhi and Prof. Dr. Jo Vansteenbergen, for their expert suggestions. My colleagues of the History Department have also been supportive by letting me share my ideas in development during research meetings at the department, lunches and visits to the pub. I would also like to sincerely thank the scholars who shared their ideas and expertise with me: Dimitris Kastritsis, Feridun Emecen, David Wrisley, Güneş Işıksel, Deborah Boucayannis, Kadir Dede, Kristof d’Hulster, Xavier Baecke and many others. -

© 2008 Hyeong-Jong

© 2011 Elise Soyun Ahn SEEING TURKISH STATE FORMATION PROCESSES: MAPPING LANGUAGE AND EDUCATION CENSUS DATA BY ELISE SOYUN AHN DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Educational Policy Studies in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2011 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Pradeep Dhillon, Chair Professor Douglas Kibbee Professor Fazal Rizvi Professor Thomas Schwandt Abstract Language provides an interesting lens to look at state-building processes because of its cross- cutting nature. For example, in addition to its symbolic value and appeal, a national language has other roles in the process, including: (a) becoming the primary medium of communication which permits the nation to function efficiently in its political and economic life, (b) promoting social cohesion, allowing the nation to develop a common culture, and (c) forming a primordial basis for self-determination. Moreover, because of its cross-cutting nature, language interventions are rarely isolated activities. Languages are adopted by speakers, taking root in and spreading between communities because they are legitimated by legislation, and then reproduced through institutions like the education and military systems. Pádraig Ó’ Riagáin (1997) makes a case for this observing that ―Language policy is formulated, implemented, and accomplishes its results within a complex interrelated set of economic, social, and political processes which include, inter alia, the operation of other non-language state policies‖ (p. 45). In the Turkish case, its foundational role in the formation of the Turkish nation-state but its linkages to human rights issues raises interesting issues about how socio-cultural practices become reproduced through institutional infrastructure formation. -

Zfwt Zeitschrift Für Die Welt Der Türken CORRUPTION of the OTTOMAN INHERITANCE SYSTEM and REFORM STUDIES CARRIED out in the 17

Zeitschrift für die Welt der Türken ZfWT Journal of World of Turks CORRUPTION OF THE OTTOMAN INHERITANCE SYSTEM AND REFORM STUDIES CARRIED OUT IN THE 17th CENTURY Zabit ACER∗ Abstract: The Turkish nation is one of the nations who have founded many States in the history and ever continued its names. Today 45 countries have been founded in the lands under the sovereignty of the Ottoman State, 31 countries under its authority and influence. The Ottoman State, being parallel to its continuously growing and following active policies in the world politics, continuously renovated itself. Contemporary and modern historians starts the stagnation of the Otoman State from late 16th century. Long lasting wars brought the corruption of economy along and the regression became inevitable when also added incompetence of the Statesmen. The most important factor in the stagnation of the Ottoman State became the change in the inheritance procedure. The corruption in the inheritance system became effective in the corruption of the army and navy. That there were great problems in Timarli Sipahis, taxes increased more and villagers fell into the hands of usurers churned agricultural system deeply and the people escaped leaving their villages. As a result, the State started the struggle to make reforms as of 17th century to eliminate emerging disorders. 17th century reforms made based on the power and violence couldn’t find much development opportunity. The most characteristic speciality of this term reforms is that they were made depending on persons. There wasn’t the effect of Europe in 119 renovations made and studies to bring the Ottoman State back to its previous powerful terms were made. -

Yemen As an Ottoman Frontier and Attempt to Build a Native Army: Asakir-I Hamidiye

YEMEN AS AN OTTOMAN FRONTIER AND ATTEMPT TO BUILD A NATIVE ARMY: ASAKİR-İ HAMİDİYE by ÖNDER EREN AKGÜL Submitted to the Graduate School of Sabancı University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Sabancı University July 2014 YEMEN AS AN OTTOMAN FRONTIER AND ATTEMPT TO BUILD A NATIVE ARMY: ASAKİR-İ HAMİDİYE APPROVED BY: Selçuk Akşin Somel …………………………. (Thesis Supervisor) Yusuf Hakan Erdem …………………………. Bahri Yılmaz …………………………. DATE OF APPROVAL: 25.07.2014 © Önder Eren Akgül 2014 All Rights Reserved YEMEN AS AN OTTOMAN FRONTIER AND ATTEMPT TO BUILD A NATIVE ARMY: ASAKİR-İ HAMİDİYE Önder Eren Akgül History, MA, 2014 Supervisor: Selçuk Akşin Somel Keywords: Colonialism, Imperialism, Native army, Ottoman frontiers, Ottoman imperialism ABSTRACT This thesis is a study of the Ottoman attempts to control its frontiers and the frontier populations by basing upon the experience of the native army (Asakir-i Hamidiye) organized by Ismail Hakkı Pasha, who was a governor of Yemen province, between 1800 and 1882. This thesis positions Yemen into the context of the literature produced for the frontier regions; and tries to investigate the dynamics of the institutions and practices pursued in Yemen that differentiated from the financial, military and judicial institutions of the Tanzimat-era. This thesis puts forth that the Ottoman Empire was not a passive audience of imperial competitions of the nineteenth century, but engaged into the imperial struggles by undertaking aggressive measures with an imperialist mind and strategy. Herein, with the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, the Ottoman ruling elites detected the Red Sea as a strategic region too. -

The London School of Economics and Political Science

The London School of Economics and Political Science The State as a Standard of Civilisation: Assembling the Modern State in Lebanon and Syria, 1800-1944 Andrew Delatolla A thesis submitted to the Department of International Relations of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, October 2017 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledge is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe on the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 101,793 words. 2 Acknowledgements This PhD has been much more than an academic learning experience, it has been a life experience and period of self-discovery. None of it would have been possible without the help and support from an amazing network of family, colleagues, and friends. First and foremost, a big thank you to the most caring, attentive, and conscientious supervisor one could hope for, Dr. Katerina Dalacoura. Her help, guidance, and critiques from the first draft chapter to the final drafts of the thesis have always been a source of clarity when there was too much clouding my thoughts. -

ALI KEMAL and the SABAH / PEYAM-I SABAH NEWSPAPER By

LIBERAL CRITICISM TOWARD THE UNIONIST POLICIES DURING THE GREAT WAR: ALI KEMAL AND THE SABAH / PEYAM-I SABAH NEWSPAPER by ONUR ÇAKMUR Submitted to the Institute of Social Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Sabancı University July 2018 © Onur Çakmur 2018 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT LIBERAL CRITICISM TOWARD THE UNIONIST POLICIES DURING THE GREAT WAR: ALİ KEMAL AND THE SABAH / PEYAM-I SABAH NEWSPAPER ONUR ÇAKMUR Master of Arts in Turkish Studies, July 2018 Thesis Advisor: Assoc. Prof. Selçuk Akşin Somel Keywords: Ali Kemal; Armistice press; First World War; Liberal opposition; Sabah newspaper The First World War that lasted from 1914 to 1918 occupies an important place in Turkish History. However, in comparison with the Turkish War of Independence, Ottoman experience of the Great War remains a relatively under-researched area. The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), which ruled the Ottoman Empire during the War, constituted a dictatorship and kept the opposition under strict censorship. During the armistice period, political pressure was lifted and the press became a platform for criticism about the wartime policies of the Unionists and its consequences. Therefore, this study primarily aims to analyze Sabah (from January 1920 onwards published as Peyam-ı Sabah), a leading newspaper of the opposition, with regard to its perspective on the War during the armistice period. The emphasis of the study will be on the editor-in- chief of the paper, Ali Kemal, an iconic figure of the period, who had been very influential especially in Sabah’s analyses regarding the War and the figures who were responsible in this debacle. -

105. Yilinda Çanakkale Muharebelerine Bakiş © T.C

105. YILINDA ÇANAKKALE MUHAREBELERİNE BAKIŞ © T.C. KÜLTÜR VE TURİZM BAKANLIĞI ÇANAKKALE SAVAŞLARI GELİBOLU TARİHİ ALAN BAŞKANLIĞI 3692 Çanakkale Savaşları Kitapları Dizisi ISBN: 978-975-17-4793-8 Editör Katkı Sunanlar Barış BORLAT Eda Karaca Burhan SAYILIR Gökşen Özen Gülper Ulusoy Editör Yardımcısı Kübra Beşkonaklıoğlu Aslıhan KERVAN Nevim Arıkan Serhat Kahyaoğlu Yayına Hazırlayan Utkan Emre Er Redaktör Yasemin BİRTANE Birinci Baskı 500 adet Ankara, 2020 Tasarım ve Baskı Kapak Fotoğrafı Miralay Mustafa Kemal (ATATÜRK) 5846 sayılı Kanun’dan doğan tüm hakları (tasarım, çoğaltma, yayma, umuma iletim, temsil ve işleme) Çanakkale Savaşları Gelibolu Tarihi Alan Başkanlığına aittir. Her hakkı saklıdır. Kaynak gösterilerek yapılacak kısa alıntılar dışında yayıncının izni olmaksızın hiçbir yolla çoğaltılamaz. 105. Yılında Çanakkale Muharebelerine Bakış. Ankara: Kültür ve Turizm Bakanlığı, 2020. 514 s.; rnk. res.: 21 cm. (Kültür ve Turizm Bakanlığı yayınları; 3692, Çanakkale Savaşları Gelibolu Tarihi Alan Başkanlığı Çanakkale Savaşları Kitapları Dizisi). ISBN: 978-975-17-4793-8 I. Borlat, Barış, Sayılır, Burhan. II. seriler 956.1 Çanakkale siperlerinde saatlerce süren ateş muharebesinden galip çıkan er bakışlı yiğitler çevresi TAKDİM Çanakkale Tarihi Alanı, Birinci Dünya Savaşı muharebe alanları içerisinde günümüze kadar korunarak gelebilen nadir sahalardan birisidir. Bu nedenle gerek Avrupa’dan gerekse ülkemizden askerî tarih çalışması yürüten değerli araştırma- cıların da önemli bir çalışma sahasıdır. Bu durumun günümüze kadar gelebilme- sinde bölgenin önce Milli Park statüsü ile koruma altına alınması daha sonra Tarihi Alan Başkanlığı idari yapısına dönüşmesinin önemli bir yeri vardır. Günümüzde de bu yaklaşım ile “açık hava müzesi” olması yolunda çalışmalarımıza devam etmek- teyiz. Çanakkale Tarihi Alanı, eskiçağdan günümüze kadar tarihlenen birçok kül- tür ve yerleşime de ev sahipliği yapmıştır. -

Faculty of Humanities

FACULTY OF HUMANITIES The Faculty of Humanities was founded in 1993 due to the restoration with the provision of law legal decision numbered 496. It is the first faculty of the country with the name of The Faculty of Humanities after 1982. The Faculty started its education with the departments of History, Sociology, Art History and Classical Archaeology. In the first two years it provided education to extern and intern students. In the academic year of 1998-1999, the Department of Art History and Archaeology were divided into two separate departments as Department of Art History and Department of Archaeology. Then, the Department of Turkish Language and Literature was founded in the academic year of 1999-2000 , the Department of Philosophy was founded in the academic year of 2007-2008 and the Department of Russian Language and Literature was founded in the academic year of 2010- 2011. English prep school is optional for all our departments. Our faculty had been established on 5962 m2 area and serving in a building which is supplied with new and technological equipments in Yunusemre Campus. In our departments many research enhancement projects and Archaeology and Art History excavations that students take place are carried on which are supported by TÜBİTAK, University Searching Fund and Ministry of Culture. Dean : Vice Dean : Prof. Dr. Feriştah ALANYALI Vice Dean : Assoc. Prof. Dr. Erkan İZNİK Secretary of Faculty : Murat TÜRKYILMAZ STAFF Professors: Feriştah ALANYALI, H. Sabri ALANYALI, Erol ALTINSAPAN, Muzaffer DOĞAN, İhsan GÜNEŞ, Bilhan -

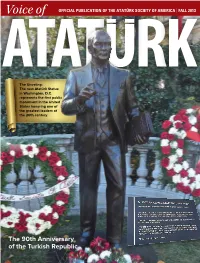

The 90Th Anniversary of the Turkish Republic CHAIRMAN’S COMMENTS the Atatürk Society of America Voice of 4731 Massachusetts Ave

Voice of OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE ATATÜRK SOCIETY OF AMERICA | FALL 2013 The Unveling: The new Atatürk Statue in Washington, D.C. represents the first public monument in the United States honoring one of the greatest leaders of the 20th century. The 90th Anniversary of the Turkish Republic CHAIRMAN’S COMMENTS The Atatürk Society of America Voice of 4731 Massachusetts Ave. NW CONTENTS Washington DC 20016 Phone 202 362 7173 Fax 202 363 4075 Mustafa Kemal’in Askerleriyiz... CHAIRMAN’S COMMENTS E-mail [email protected] 03 www.Ataturksociety.org Reversal of the Atatürk miracle— We are the soldiers of Mustafa Kemal... Destruction of Secular Democracy EXECUTIVE BOARD “There are two Mustafa Kemals. One, the flesh-and-blood Mustafa Kemal who now stands before Hudai Yavalar you and who will pass away. The other is you, all of you here who will go to the far corners of our President land to spread the ideals which must be defended with your lives if necessary. I stand for the nation's Prof. Bülent Atalay PRESIDENT’S COMMENTS dreams, and my life's work is to make them come true.” 04 Vice President —Mustafa Kemal Atatürk 10th of November — A day to Mourn Filiz Odabas-Geldiay Dr. Bulent Atalay Treasurer Members Believing secularism , democracy, science and technology Mirat Yavalar Aynur Uluatam Sumer 06 he year 2013 marked the 90th anniversary of the founding of the Turkish Republic. And ASA NEWS Secretary Ilknur Boray Hudai Yavalar 05 it was also the year of the most significant uprising in the history of Turkey. The chant Lecture by Dr. -

Yemen Valisi Ahmed Muhtar Paşa Dönemi Ve Yemen’De Osmanli Idaresi (1868-1909)

Çağdaş Türkiye Tarihi Araştırmaları Dergisi Journal Of Modern Turkish History Studies Geliş Tarihi : 02.08.2016 Kabul Tarihi: 26.07.2017 XVII/34 (2017-Bahar/Spring), ss. 5-42. YEMEN VALİSİ AHMED MUHTAR PAŞA DÖNEMİ VE YEMEN’DE OSMANLI İDARESİ (1868-1909) Durmuş AKALIN* Kamuran ŞİMŞEK** Öz Arap Yarımadası’nın güneyinde yer alan Yemen, Osmanlı Devleti sınırlarına dâhil olduğu andan itibaren son derece önem atfedilen topraklardan biri olmuştur. Osmanlı hâkimiyeti ilk olarak Yavuz Sultan Selim zamanında başlamışsa da asıl topraklara dâhil ediliş Hadım Süleyman Paşa iledir. Ne var ki bir süre devam eden hâkimiyetin ardından bölgeden çekilen Osmanlı idaresi, 1849’da Kıbrıslı Muavin Tevfik Paşa ile tekrar başlamıştır. 19. yüzyılın ortalarında Mısır ve Hicaz’dan toplanan kuvvetlerle girişilen bu operasyon sonuçsuz kalınca, Ahmed Muhtar Paşa’nın valiliğine kadar bölgede bir asayiş tesis edilememiştir. Yemen’de idarenin tesisini güçleştiren başlıca hadise sık sık yaşanan isyanlar olmuştur. Yemen’in bu karışık döneminde, İngilizler Aden’e yerleşmişler ve Süveyş Kanalı’nın açılmasıyla birlikte nüfuzlarını daha da arttırmışlardır. Bir süre sonra sadece İngilizler değil, başka büyük güçler de Kızıldeniz etrafına yerleşmeye başlamışlardır. Ancak Ahmed Muhtar Paşa, Yemen’de görev yaptığı süre içinde büyük bir askeri harekâta girişmiştir. Başarılı olan bu harekâtın neticesinde Ahmed Muhtar Paşa, mülki ve askeri alanda yeni bir teşkilatlanmaya teşebbüs etmiştir. Bu çalışmada Yemen’in önemi ve Ahmed Muhtar Paşa’nın valiliği üzerinde durulacaktır. Böylece bölgede girişilen faaliyetler ve Osmanlı Devleti’nin Yemen’deki varlığıyla ilgili bilgi birikimine bir zenginlik kazandırılması düşünülmektedir. Anahtar Kelimeler: Ahmed Muhtar Paşa, Osmanlı Devleti, Yemen, Kızıldeniz, San’a. THE GOVERNORATE OF YEMEN OF AHMED MUHTAR PASHA AND THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE OTTOMAN ADMINISTRATION IN YEMEN (1868-1909) Abstract The Yemen, located in the south of Arabian Peninsula, was one of the most important attributed to soil since Yemen was included in the Ottoman state borders.