Evolution of Lunar Polar Ice Stability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

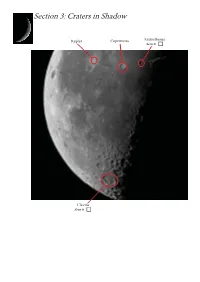

Craters in Shadow

Section 3: Craters in Shadow Kepler Copernicus Eratosthenes Seen it Clavius Seen it Section 3: Craters in Shadow Visibility: A pair of binoculars is the minimum requirement to see these features. When: Look for them when the terminator’s close by, typically a day before last quarter. Not all craters are best seen when the Sun is high in the lunar sky - in fact most aren’t! If craters aren’t par- ticularly bright or dark, they tend to disappear into the background when the Moon’s phase is close to full. These craters are best seen when the ‘terminator’ is nearby, or when the Sun is low in the lunar sky as seen from the crater. This causes oblique lighting to fall on the crater and create exaggerated shadows. Ultimately, this makes the crater look more dramatic and easier to see. We’ll use this effect for the next section on lunar mountains, but before we do, there are a couple of craters that we’d like to bring to your attention. Actually, the Moon is covered with a whole host of wonderful craters that look amazing when the lighting is oblique. During the summer and into the early autumn, it’s the later phases of the Moon are best positioned in the sky - the phases following full Moon. Unfortunately, this means viewing in the early hours but don’t worry as we’ve kept things simple. We just want to give you a taste of what a shadowed crater looks like for this marathon, so the going here is really pretty easy! First, locate the two craters Kepler and Copernicus which were marathon targets pointed out in Section 2. -

Planning a Mission to the Lunar South Pole

Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter: (Diviner) Audience Planning a Mission to Grades 9-10 the Lunar South Pole Time Recommended 1-2 hours AAAS STANDARDS Learning Objectives: • 12A/H1: Exhibit traits such as curiosity, honesty, open- • Learn about recent discoveries in lunar science. ness, and skepticism when making investigations, and value those traits in others. • Deduce information from various sources of scientific data. • 12E/H4: Insist that the key assumptions and reasoning in • Use critical thinking to compare and evaluate different datasets. any argument—whether one’s own or that of others—be • Participate in team-based decision-making. made explicit; analyze the arguments for flawed assump- • Use logical arguments and supporting information to justify decisions. tions, flawed reasoning, or both; and be critical of the claims if any flaws in the argument are found. • 4A/H3: Increasingly sophisticated technology is used Preparation: to learn about the universe. Visual, radio, and X-ray See teacher procedure for any details. telescopes collect information from across the entire spectrum of electromagnetic waves; computers handle Background Information: data and complicated computations to interpret them; space probes send back data and materials from The Moon’s surface thermal environment is among the most extreme of any remote parts of the solar system; and accelerators give planetary body in the solar system. With no atmosphere to store heat or filter subatomic particles energies that simulate conditions in the Sun’s radiation, midday temperatures on the Moon’s surface can reach the stars and in the early history of the universe before 127°C (hotter than boiling water) whereas at night they can fall as low as stars formed. -

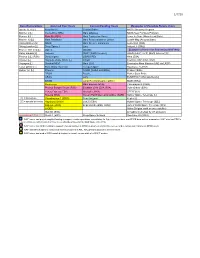

List of Missions Using SPICE (PDF)

1/7/20 Data Restorations Selected Past Users Current/Pending Users Examples of Possible Future Users Apollo 15, 16 [L] Magellan [L] Cassini Orbiter NASA Discovery Program Mariner 2 [L] Clementine (NRL) Mars Odyssey NASA New Frontiers Program Mariner 9 [L] Mars 96 (RSA) Mars Exploration Rover Lunar IceCube (Moorehead State) Mariner 10 [L] Mars Pathfinder Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter LunaH-Map (Arizona State) Viking Orbiters [L] NEAR Mars Science Laboratory Luna-Glob (RSA) Viking Landers [L] Deep Space 1 Juno Aditya-L1 (ISRO) Pioneer 10/11/12 [L] Galileo MAVEN Examples of Users not Requesting NAIF Help Haley armada [L] Genesis SMAP (Earth Science) GOLD (LASP, UCF) (Earth Science) [L] Phobos 2 [L] (RSA) Deep Impact OSIRIS REx Hera (ESA) Ulysses [L] Huygens Probe (ESA) [L] InSight ExoMars RSP (ESA, RSA) Voyagers [L] Stardust/NExT Mars 2020 Emmirates Mars Mission (UAE via LASP) Lunar Orbiter [L] Mars Global Surveyor Europa Clipper Hayabusa-2 (JAXA) Helios 1,2 [L] Phoenix NISAR (NASA and ISRO) Proba-3 (ESA) EPOXI Psyche Parker Solar Probe GRAIL Lucy EUMETSAT GEO satellites [L] DAWN Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter MOM (ISRO) Messenger Mars Express (ESA) Chandrayan-2 (ISRO) Phobos Sample Return (RSA) ExoMars 2016 (ESA, RSA) Solar Orbiter (ESA) Venus Express (ESA) Akatsuki (JAXA) STEREO [L] Rosetta (ESA) Korean Pathfinder Lunar Orbiter (KARI) Spitzer Space Telescope [L] [L] = limited use Chandrayaan-1 (ISRO) New Horizons Kepler [L] [S] = special services Hayabusa (JAXA) JUICE (ESA) Hubble Space Telescope [S][L] Kaguya (JAXA) Bepicolombo (ESA, JAXA) James Webb Space Telescope [S][L] LADEE Altius (Belgian earth science satellite) ISO [S] (ESA) Armadillo (CubeSat, by UT at Austin) Last updated: 1/7/20 Smart-1 (ESA) Deep Space Network Spectrum-RG (RSA) NAIF has or had project-supplied funding to support mission operations, consultation for flight team members, and SPICE data archive preparation. -

10Great Features for Moon Watchers

Sinus Aestuum is a lava pond hemming the Imbrium debris. Mare Orientale is another of the Moon’s large impact basins, Beginning observing On its eastern edge, dark volcanic material erupted explosively and possibly the youngest. Lunar scientists think it formed 170 along a rille. Although this region at first appears featureless, million years after Mare Imbrium. And although “Mare Orien- observe it at several different lunar phases and you’ll see the tale” translates to “Eastern Sea,” in 1961, the International dark area grow more apparent as the Sun climbs higher. Astronomical Union changed the way astronomers denote great features for Occupying a region below and a bit left of the Moon’s dead lunar directions. The result is that Mare Orientale now sits on center, Mare Nubium lies far from many lunar showpiece sites. the Moon’s western limb. From Earth we never see most of it. Look for it as the dark region above magnificent Tycho Crater. When you observe the Cauchy Domes, you’ll be looking at Yet this small region, where lava plains meet highlands, con- shield volcanoes that erupted from lunar vents. The lava cooled Moon watchers tains a variety of interesting geologic features — impact craters, slowly, so it had a chance to spread and form gentle slopes. 10Our natural satellite offers plenty of targets you can spot through any size telescope. lava-flooded plains, tectonic faulting, and debris from distant In a geologic sense, our Moon is now quiet. The only events by Michael E. Bakich impacts — that are great for telescopic exploring. -

Relative Ages

CONTENTS Page Introduction ...................................................... 123 Stratigraphic nomenclature ........................................ 123 Superpositions ................................................... 125 Mare-crater relations .......................................... 125 Crater-crater relations .......................................... 127 Basin-crater relations .......................................... 127 Mapping conventions .......................................... 127 Crater dating .................................................... 129 General principles ............................................. 129 Size-frequency relations ........................................ 129 Morphology of large craters .................................... 129 Morphology of small craters, by Newell J. Fask .................. 131 D, method .................................................... 133 Summary ........................................................ 133 table 7.1). The first three of these sequences, which are older than INTRODUCTION the visible mare materials, are also dominated internally by the The goals of both terrestrial and lunar stratigraphy are to inte- deposits of basins. The fourth (youngest) sequence consists of mare grate geologic units into a stratigraphic column applicable over the and crater materials. This chapter explains the general methods of whole planet and to calibrate this column with absolute ages. The stratigraphic analysis that are employed in the next six chapters first step in reconstructing -

![Arxiv:2003.06799V2 [Astro-Ph.EP] 6 Feb 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4215/arxiv-2003-06799v2-astro-ph-ep-6-feb-2021-614215.webp)

Arxiv:2003.06799V2 [Astro-Ph.EP] 6 Feb 2021

Thomas Ruedas1,2 Doris Breuer2 Electrical and seismological structure of the martian mantle and the detectability of impact-generated anomalies final version 18 September 2020 published: Icarus 358, 114176 (2021) 1Museum für Naturkunde Berlin, Germany 2Institute of Planetary Research, German Aerospace Center (DLR), Berlin, Germany arXiv:2003.06799v2 [astro-ph.EP] 6 Feb 2021 The version of record is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2020.114176. This author pre-print version is shared under the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). Electrical and seismological structure of the martian mantle and the detectability of impact-generated anomalies Thomas Ruedas∗ Museum für Naturkunde Berlin, Germany Institute of Planetary Research, German Aerospace Center (DLR), Berlin, Germany Doris Breuer Institute of Planetary Research, German Aerospace Center (DLR), Berlin, Germany Highlights • Geophysical subsurface impact signatures are detectable under favorable conditions. • A combination of several methods will be necessary for basin identification. • Electromagnetic methods are most promising for investigating water concentrations. • Signatures hold information about impact melt dynamics. Mars, interior; Impact processes Abstract We derive synthetic electrical conductivity, seismic velocity, and density distributions from the results of martian mantle convection models affected by basin-forming meteorite impacts. The electrical conductivity features an intermediate minimum in the strongly depleted topmost mantle, sandwiched between higher conductivities in the lower crust and a smooth increase toward almost constant high values at depths greater than 400 km. The bulk sound speed increases mostly smoothly throughout the mantle, with only one marked change at the appearance of β-olivine near 1100 km depth. -

Astrophysics

National Aeronautics and Space Administration Astrophysics Committee on NASA Science Paul Hertz Mission Extensions Director, Astrophysics Division NRC Keck Center Science Mission Directorate Washington DC @PHertzNASA February 1-2, 2016 Why Astrophysics? Astrophysics is humankind’s scientific endeavor to understand the universe and our place in it. 1. How did our universe 2. How did galaxies, stars, 3. Are We Alone? begin and evolve? and planets come to be? These national strategic drivers are enduring 1972 1982 1991 2001 2010 2 Astrophysics Driving Documents http://science.nasa.gov/astrophysics/documents 3 Astrophysics Programs Physics of the Cosmos Cosmic Origins Exoplanet Exploration Program Program Program 1. How did our universe 2. How did galaxies, stars, 3. Are We Alone? begin and evolve? and planets come to be? Astrophysics Explorers Program Astrophysics Research Program James Webb Space Telescope Program (managed outside of Astrophysics Division until commissioning) 4 Astrophysics Programs and Missions Physics of the Cosmos Cosmic Origins Exoplanet Exploration Program Program Program Chandra Hubble Spitzer Kepler/K2 XMM-Newton (ESA) Herschel (ESA) WFIRST Fermi SOFIA Planck (ESA) LISA Pathfinder (ESA) Astrophysics Explorers Program Euclid (ESA) NuSTAR Swift Suzaku (JAXA) Athena (ESA) ASTRO-H (JAXA) NICER TESS L3 GW Obs (ESA) 3 SMEX and 2 MO in Phase A James Webb Space Telescope Program: Webb 5 Astrophysics Programs and Missions Physics of the Cosmos Cosmic Origins Exoplanet Exploration Program Program Program Missions in extended phase Chandra Hubble Spitzer Kepler/K2 XMM-Newton (ESA) Herschel (ESA) WFIRST Fermi SOFIA Planck (ESA) LISA Pathfinder (ESA) Astrophysics Explorers Program Euclid (ESA) NuSTAR Swift Suzaku (JAXA) Athena (ESA) ASTRO-H (JAXA) NICER TESS L3 GW Obs (ESA) 3 SMEX and 2 MO in Phase A James Webb Space Telescope Program: Webb 6 Astrophysics Mission Portfolio • NASA Astrophysics seeks to advance NASA’s strategic objectives in astrophysics as well as the science priorities of the Decadal Survey in Astronomy and Astrophysics. -

Preliminary Science Report

7. Photographic Summary of Apollo 77 Mission James H. Sasser The geographical exploration of new frontiers mil Estar polyester base. Ektachrome EF S016S has usually occurred many years before scien- color film on a 2.5-mil Estar polyester base was tists visited and studied the areas in detail. For exposed on the lunar surface. Thc higher speed example, the existence of Antarctica as a conti- of this color film was expected to be more suit- nent was known from the time Charles Wilkes able for lunar surface photography because of explored 1500 miles of the coastline in 1840. tl~elow light levels anticipated and confirmed However, extensive Antarctic exploration did to exist on the lunar surface. Other color 70-mm not begin until the 20th century with the voy- exposures of the Earth and Moon were taken ages of Scott, Amundsen, Shackleton, and Byrd. on Ektachrome MS S036S color reversal film It was not until the International Geophysical on a 2.5-mil Estar polyester base. Year (July 1957 to December 1958) that scien- The 16-mm film taken during lunar module tists from 12 countries began conducting an (LM) descent provided the first accurate knowl- ambitious Antarctic research program. In this edge of the exact landing point on the lunar respect, the first manned lunar exploration was surface. The 70-mm photographs taken on the unique. The scientific experiments were care- lunar surface provided panoramic views of the fully planned, and the astronauts were trained surface near the landed LM and allowed de- as surrogates for scientists representing many tailed topographic mapping of the lunar surface disciplines. -

PROJECT PENGUIN Robotic Lunar Crater Resource Prospecting VIRGINIA POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE & STATE UNIVERSITY Kevin T

PROJECT PENGUIN Robotic Lunar Crater Resource Prospecting VIRGINIA POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE & STATE UNIVERSITY Kevin T. Crofton Department of Aerospace & Ocean Engineering TEAM LEAD Allison Quinn STUDENT MEMBERS Ethan LeBoeuf Brian McLemore Peter Bradley Smith Amanda Swanson Michael Valosin III Vidya Vishwanathan FACULTY SUPERVISOR AIAA 2018 Undergraduate Spacecraft Design Dr. Kevin Shinpaugh Competition Submission i AIAA Member Numbers and Signatures Ethan LeBoeuf Brian McLemore Member Number: 918782 Member Number: 908372 Allison Quinn Peter Bradley Smith Member Number: 920552 Member Number: 530342 Amanda Swanson Michael Valosin III Member Number: 920793 Member Number: 908465 Vidya Vishwanathan Dr. Kevin Shinpaugh Member Number: 608701 Member Number: 25807 ii Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................................................................ v List of Tables ................................................................................................................................................................vi List of Symbols ........................................................................................................................................................... vii I. Team Structure ........................................................................................................................................................... 1 II. Introduction .............................................................................................................................................................. -

Antarctic Treaty Handbook

Annex Proposed Renumbering of Antarctic Protected Areas Existing SPA’s Existing Site Proposed Year Annex V No. New Site Management Plan No. Adopted ‘Taylor Rookery 1 101 1992 Rookery Islands 2 102 1992 Ardery Island and Odbert Island 3 103 1992 Sabrina Island 4 104 Beaufort Island 5 105 Cape Crozier [redesignated as SSSI no.4] - - Cape Hallet 7 106 Dion Islands 8 107 Green Island 9 108 Byers Peninsula [redesignated as SSSI no. 6] - - Cape Shireff [redesignated as SSSI no. 32] - - Fildes Peninsula [redesignated as SSSI no.5] - - Moe Island 13 109 1995 Lynch Island 14 110 Southern Powell Island 15 111 1995 Coppermine Peninsula 16 112 Litchfield Island 17 113 North Coronation Island 18 114 Lagotellerie Island 19 115 New College Valley 20 116 1992 Avian Island (was SSSI no. 30) 21 117 ‘Cryptogram Ridge’ 22 118 Forlidas and Davis Valley Ponds 23 119 Pointe-Geologic Archipelago 24 120 1995 Cape Royds 1 121 Arrival Heights 2 122 Barwick Valley 3 123 Cape Crozier (was SPA no. 6) 4 124 Fildes Peninsula (was SPA no. 12) 5 125 Byers Peninsula (was SPA no. 10) 6 126 Haswell Island 7 127 Western Shore of Admiralty Bay 8 128 Rothera Point 9 129 Caughley Beach 10 116 1995 ‘Tramway Ridge’ 11 130 Canada Glacier 12 131 Potter Peninsula 13 132 Existing SPA’s Existing Site Proposed Year Annex V No. New Site Management Plan No. Adopted Harmony Point 14 133 Cierva Point 15 134 North-east Bailey Peninsula 16 135 Clark Peninsula 17 136 North-west White Island 18 137 Linnaeus Terrace 19 138 Biscoe Point 20 139 Parts of Deception Island 21 140 ‘Yukidori Valley’ 22 141 Svarthmaren 23 142 Summit of Mount Melbourne 24 118 ‘Marine Plain’ 25 143 Chile Bay 26 144 Port Foster 27 145 South Bay 28 146 Ablation Point 29 147 Avian Island [redesignated as SPA no. -

Redacted for Privacy Abstract Approved: John V

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF MIAH ALLAN BEAL for the Doctor of Philosophy (Name) (Degree) in Oceanography presented on August 12.1968 (Major) (Date) Title:Batymety and_Strictuof_thp..4rctic_Ocean Redacted for Privacy Abstract approved: John V. The history of the explordtion of the Central Arctic Ocean is reviewed.It has been only within the last 15 years that any signifi- cant number of depth-sounding data have been collected.The present study uses seven million echo soundings collected by U. S. Navy nuclear submarines along nearly 40, 000 km of track to construct, for the first time, a reasonably complete picture of the physiography of the basin of the Arctic Ocean.The use of nuclear submarines as under-ice survey ships is discussed. The physiography of the entire Arctic basin and of each of the major features in the basin are described, illustrated and named. The dominant ocean floor features are three mountain ranges, generally paralleling each other and the 40°E. 140°W. meridian. From the Pacific- side of the Arctic basin toward the Atlantic, they are: The Alpha Cordillera; The Lomonosov Ridge; andThe Nansen Cordillera. The Alpha Cordillera is the widest of the three mountain ranges. It abuts the continental slopes off the Canadian Archipelago and off Asia across more than550of longitude on each slope.Its minimum width of about 300 km is located midway between North America and Asia.In cross section, the Alpha Cordillera is a broad arch rising about two km, above the floor of the basin.The arch is marked by volcanoes and regions of "high fractured plateau, and by scarps500to 1000 meters high.The small number of data from seismology, heat flow, magnetics and gravity studies are reviewed.The Alpha Cordillera is interpreted to be an inactive mid-ocean ridge which has undergone some subsidence. -

Strategies for Detecting Biological Molecules on Titan

ASTROBIOLOGY Volume 18, Number 5, 2018 ª Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. DOI: 10.1089/ast.2017.1758 Strategies for Detecting Biological Molecules on Titan Catherine D. Neish,1 Ralph D. Lorenz,2 Elizabeth P. Turtle,2 Jason W. Barnes,3 Melissa G. Trainer,4 Bryan Stiles,5 Randolph Kirk,6 Charles A. Hibbitts,2 and Michael J. Malaska5 Abstract Saturn’s moon Titan has all the ingredients needed to produce ‘‘life as we know it.’’ When exposed to liquid water, organic molecules analogous to those found on Titan produce a range of biomolecules such as amino acids. Titan thus provides a natural laboratory for studying the products of prebiotic chemistry. In this work, we examine the ideal locales to search for evidence of, or progression toward, life on Titan. We determine that the best sites to identify biological molecules are deposits of impact melt on the floors of large, fresh impact craters, specifically Sinlap, Selk, and Menrva craters. We find that it is not possible to identify biomolecules on Titan through remote sensing, but rather through in situ measurements capable of identifying a wide range of biological molecules. Given the nonuniformity of impact melt exposures on the floor of a weathered impact crater, the ideal lander would be capable of precision targeting. This would allow it to identify the locations of fresh impact melt deposits, and/or sites where the melt deposits have been exposed through erosion or mass wasting. Determining the extent of prebiotic chemistry within these melt deposits would help us to understand how life could originate on a world very different from Earth.