Evidence for Exposed Water Ice in the Moon's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SPECIAL Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 Collides with Jupiter

SL-9/JUPITER ENCOUNTER - SPECIAL Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 Collides with Jupiter THE CONTINUATION OF A UNIQUE EXPERIENCE R.M. WEST, ESO-Garching After the Storm Six Hectic Days in July eration during the first nights and, as in other places, an extremely rich data The recent demise of comet Shoe ESO was but one of many profes material was secured. It quickly became maker-Levy 9, for simplicity often re sional observatories where observations evident that infrared observations, es ferred to as "SL-9", was indeed spectac had been planned long before the critical pecially imaging with the far-IR instru ular. The dramatic collision of its many period of the "SL-9" event, July 16-22, ment TIMMI at the 3.6-metre telescope, fragments with the giant planet Jupiter 1994. It is now clear that practically all were perfectly feasible also during day during six hectic days in July 1994 will major observatories in the world were in time, and in the end more than 120,000 pass into the annals of astronomy as volved in some way, via their telescopes, images were obtained with this facility. one of the most incredible events ever their scientists or both. The only excep The programmes at most of the other predicted and witnessed by members of tions may have been a few observing La Silla telescopes were also successful, this profession. And never before has a sites at the northernmost latitudes where and many more Gigabytes of data were remote astronomical event been so ac the bright summer nights and the very recorded with them. -

A Wunda-Full World? Carbon Dioxide Ice Deposits on Umbriel and Other Uranian Moons

Icarus 290 (2017) 1–13 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Icarus journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/icarus A Wunda-full world? Carbon dioxide ice deposits on Umbriel and other Uranian moons ∗ Michael M. Sori , Jonathan Bapst, Ali M. Bramson, Shane Byrne, Margaret E. Landis Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Carbon dioxide has been detected on the trailing hemispheres of several Uranian satellites, but the exact Received 22 June 2016 nature and distribution of the molecules remain unknown. One such satellite, Umbriel, has a prominent Revised 28 January 2017 high albedo annulus-shaped feature within the 131-km-diameter impact crater Wunda. We hypothesize Accepted 28 February 2017 that this feature is a solid deposit of CO ice. We combine thermal and ballistic transport modeling to Available online 2 March 2017 2 study the evolution of CO 2 molecules on the surface of Umbriel, a high-obliquity ( ∼98 °) body. Consid- ering processes such as sublimation and Jeans escape, we find that CO 2 ice migrates to low latitudes on geologically short (100s–1000 s of years) timescales. Crater morphology and location create a local cold trap inside Wunda, and the slopes of crater walls and a central peak explain the deposit’s annular shape. The high albedo and thermal inertia of CO 2 ice relative to regolith allows deposits 15-m-thick or greater to be stable over the age of the solar system. -

The Cold Traps Near South Pole of the Moon

THE COLD TRAPS NEAR SOUTH POLE OF THE MOON. Berezhnoy A.A., Kozlova E.A., Shevchenko V.V. Sternberg State Astronomical Institute, Moscow University, Russia, Moscow, Universitetski pr., 13, 199992. [email protected] According to the data from “Lunar Let us note that NH3 content in the lunar Prospector” [1] the areas of high hydrogen regolith is relatively low, because the main N- content in the lunar south pole region coincide containing compound is molecular nitrogen here with the areas of such craters as Faustini (87.2º [5]. The stability of SO2 subsurface ice requires S, 75.8º E), Cabeus (85.2º S, 323º E) and other the diurnal surface temperature of less than 65 crates. We have allocated a number of craters K. However, volatile species may be which can be considered as "cold traps " in the chemisorbed by the dust particles at the surface. south pole region of the Moon (Figure 1). Some In this case we can expect the existence of from these craters has properties similar to those chemisorbed water, CO2, and SO2 at the content of the echo coming from icy satellites of Jupiter less than 0.1 wt%. and from the southern polar cap of Mars. Polar rovers or penetrators with mass We estimate the total permanently spectrometers can detect these species. For shadowed area in the lunar northern polar region solving the question of the origin of lunar polar at 28 260,2 km2. The total permanently volatiles we must determine isotopic shadowed area in the region of the south pole of composition of these species. -

LCROSS (Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite) Observation Campaign: Strategies, Implementation, and Lessons Learned

Space Sci Rev DOI 10.1007/s11214-011-9759-y LCROSS (Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite) Observation Campaign: Strategies, Implementation, and Lessons Learned Jennifer L. Heldmann · Anthony Colaprete · Diane H. Wooden · Robert F. Ackermann · David D. Acton · Peter R. Backus · Vanessa Bailey · Jesse G. Ball · William C. Barott · Samantha K. Blair · Marc W. Buie · Shawn Callahan · Nancy J. Chanover · Young-Jun Choi · Al Conrad · Dolores M. Coulson · Kirk B. Crawford · Russell DeHart · Imke de Pater · Michael Disanti · James R. Forster · Reiko Furusho · Tetsuharu Fuse · Tom Geballe · J. Duane Gibson · David Goldstein · Stephen A. Gregory · David J. Gutierrez · Ryan T. Hamilton · Taiga Hamura · David E. Harker · Gerry R. Harp · Junichi Haruyama · Morag Hastie · Yutaka Hayano · Phillip Hinz · Peng K. Hong · Steven P. James · Toshihiko Kadono · Hideyo Kawakita · Michael S. Kelley · Daryl L. Kim · Kosuke Kurosawa · Duk-Hang Lee · Michael Long · Paul G. Lucey · Keith Marach · Anthony C. Matulonis · Richard M. McDermid · Russet McMillan · Charles Miller · Hong-Kyu Moon · Ryosuke Nakamura · Hirotomo Noda · Natsuko Okamura · Lawrence Ong · Dallan Porter · Jeffery J. Puschell · John T. Rayner · J. Jedadiah Rembold · Katherine C. Roth · Richard J. Rudy · Ray W. Russell · Eileen V. Ryan · William H. Ryan · Tomohiko Sekiguchi · Yasuhito Sekine · Mark A. Skinner · Mitsuru Sôma · Andrew W. Stephens · Alex Storrs · Robert M. Suggs · Seiji Sugita · Eon-Chang Sung · Naruhisa Takatoh · Jill C. Tarter · Scott M. Taylor · Hiroshi Terada · Chadwick J. Trujillo · Vidhya Vaitheeswaran · Faith Vilas · Brian D. Walls · Jun-ihi Watanabe · William J. Welch · Charles E. Woodward · Hong-Suh Yim · Eliot F. Young Received: 9 October 2010 / Accepted: 8 February 2011 © The Author(s) 2011. -

No. 40. the System of Lunar Craters, Quadrant Ii Alice P

NO. 40. THE SYSTEM OF LUNAR CRATERS, QUADRANT II by D. W. G. ARTHUR, ALICE P. AGNIERAY, RUTH A. HORVATH ,tl l C.A. WOOD AND C. R. CHAPMAN \_9 (_ /_) March 14, 1964 ABSTRACT The designation, diameter, position, central-peak information, and state of completeness arc listed for each discernible crater in the second lunar quadrant with a diameter exceeding 3.5 km. The catalog contains more than 2,000 items and is illustrated by a map in 11 sections. his Communication is the second part of The However, since we also have suppressed many Greek System of Lunar Craters, which is a catalog in letters used by these authorities, there was need for four parts of all craters recognizable with reasonable some care in the incorporation of new letters to certainty on photographs and having diameters avoid confusion. Accordingly, the Greek letters greater than 3.5 kilometers. Thus it is a continua- added by us are always different from those that tion of Comm. LPL No. 30 of September 1963. The have been suppressed. Observers who wish may use format is the same except for some minor changes the omitted symbols of Blagg and Miiller without to improve clarity and legibility. The information in fear of ambiguity. the text of Comm. LPL No. 30 therefore applies to The photographic coverage of the second quad- this Communication also. rant is by no means uniform in quality, and certain Some of the minor changes mentioned above phases are not well represented. Thus for small cra- have been introduced because of the particular ters in certain longitudes there are no good determi- nature of the second lunar quadrant, most of which nations of the diameters, and our values are little is covered by the dark areas Mare Imbrium and better than rough estimates. -

Glossary Glossary

Glossary Glossary Albedo A measure of an object’s reflectivity. A pure white reflecting surface has an albedo of 1.0 (100%). A pitch-black, nonreflecting surface has an albedo of 0.0. The Moon is a fairly dark object with a combined albedo of 0.07 (reflecting 7% of the sunlight that falls upon it). The albedo range of the lunar maria is between 0.05 and 0.08. The brighter highlands have an albedo range from 0.09 to 0.15. Anorthosite Rocks rich in the mineral feldspar, making up much of the Moon’s bright highland regions. Aperture The diameter of a telescope’s objective lens or primary mirror. Apogee The point in the Moon’s orbit where it is furthest from the Earth. At apogee, the Moon can reach a maximum distance of 406,700 km from the Earth. Apollo The manned lunar program of the United States. Between July 1969 and December 1972, six Apollo missions landed on the Moon, allowing a total of 12 astronauts to explore its surface. Asteroid A minor planet. A large solid body of rock in orbit around the Sun. Banded crater A crater that displays dusky linear tracts on its inner walls and/or floor. 250 Basalt A dark, fine-grained volcanic rock, low in silicon, with a low viscosity. Basaltic material fills many of the Moon’s major basins, especially on the near side. Glossary Basin A very large circular impact structure (usually comprising multiple concentric rings) that usually displays some degree of flooding with lava. The largest and most conspicuous lava- flooded basins on the Moon are found on the near side, and most are filled to their outer edges with mare basalts. -

Project Selene: AIAA Lunar Base Camp

Project Selene: AIAA Lunar Base Camp AIAA Space Mission System 2019-2020 Virginia Tech Aerospace Engineering Faculty Advisor : Dr. Kevin Shinpaugh Team Members : Olivia Arthur, Bobby Aselford, Michel Becker, Patrick Crandall, Heidi Engebreth, Maedini Jayaprakash, Logan Lark, Nico Ortiz, Matthew Pieczynski, Brendan Ventura Member AIAA Number Member AIAA Number And Signature And Signature Faculty Advisor 25807 Dr. Kevin Shinpaugh Brendan Ventura 1109196 Matthew Pieczynski 936900 Team Lead/Operations Logan Lark 902106 Heidi Engebreth 1109232 Structures & Environment Patrick Crandall 1109193 Olivia Arthur 999589 Power & Thermal Maedini Jayaprakash 1085663 Robert Aselford 1109195 CCDH/Operations Michel Becker 1109194 Nico Ortiz 1109533 Attitude, Trajectory, Orbits and Launch Vehicles Contents 1 Symbols and Acronyms 8 2 Executive Summary 9 3 Preface and Introduction 13 3.1 Project Management . 13 3.2 Problem Definition . 14 3.2.1 Background and Motivation . 14 3.2.2 RFP and Description . 14 3.2.3 Project Scope . 15 3.2.4 Disciplines . 15 3.2.5 Societal Sectors . 15 3.2.6 Assumptions . 16 3.2.7 Relevant Capital and Resources . 16 4 Value System Design 17 4.1 Introduction . 17 4.2 Analytical Hierarchical Process . 17 4.2.1 Longevity . 18 4.2.2 Expandability . 19 4.2.3 Scientific Return . 19 4.2.4 Risk . 20 4.2.5 Cost . 21 5 Initial Concept of Operations 21 5.1 Orbital Analysis . 22 5.2 Launch Vehicles . 22 6 Habitat Location 25 6.1 Introduction . 25 6.2 Region Selection . 25 6.3 Locations of Interest . 26 6.4 Eliminated Locations . 26 6.5 Remaining Locations . 27 6.6 Chosen Location . -

Planetary Surfaces

Chapter 4 PLANETARY SURFACES 4.1 The Absence of Bedrock A striking and obvious observation is that at full Moon, the lunar surface is bright from limb to limb, with only limited darkening toward the edges. Since this effect is not consistent with the intensity of light reflected from a smooth sphere, pre-Apollo observers concluded that the upper surface was porous on a centimeter scale and had the properties of dust. The thickness of the dust layer was a critical question for landing on the surface. The general view was that a layer a few meters thick of rubble and dust from the meteorite bombardment covered the surface. Alternative views called for kilometer thicknesses of fine dust, filling the maria. The unmanned missions, notably Surveyor, resolved questions about the nature and bearing strength of the surface. However, a somewhat surprising feature of the lunar surface was the completeness of the mantle or blanket of debris. Bedrock exposures are extremely rare, the occurrence in the wall of Hadley Rille (Fig. 6.6) being the only one which was observed closely during the Apollo missions. Fragments of rock excavated during meteorite impact are, of course, common, and provided both samples and evidence of co,mpetent rock layers at shallow levels in the mare basins. Freshly exposed surface material (e.g., bright rays from craters such as Tycho) darken with time due mainly to the production of glass during micro- meteorite impacts. Since some magnetic anomalies correlate with unusually bright regions, the solar wind bombardment (which is strongly deflected by the magnetic anomalies) may also be responsible for darkening the surface [I]. -

Chance, Luck and Statistics : the Science of Chance

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Alberta Gambling Research Institute Alberta Gambling Research Institute 1963 Chance, luck and statistics : the science of chance Levinson, Horace C. Dover Publications, Inc. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/41334 book Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca Chance, Luck and Statistics THE SCIENCE OF CHANCE (formerly titled: The Science of Chance) BY Horace C. Levinson, Ph. D. Dover Publications, Inc., New York Copyright @ 1939, 1950, 1963 by Horace C. Levinson All rights reserved under Pan American and International Copyright Conventions. Published in Canada by General Publishing Company, Ltd., 30 Lesmill Road, Don Mills, Toronto, Ontario. Published in the United Kingdom by Constable and Company, Ltd., 10 Orange Street, London, W.C. 2. This new Dover edition, first published in 1963. is a revised and enlarged version ot the work pub- lished by Rinehart & Company in 1950 under the former title: The Science of Chance. The first edi- tion of this work, published in 1939, was called Your Chance to Win. International Standard Rook Number: 0-486-21007-3 Libraiy of Congress Catalog Card Number: 63-3453 Manufactured in the United States of America Dover Publications, Inc. 180 Varick Street New York, N.Y. 10014 PREFACE TO DOVER EDITION THE present edition is essentially unchanged from that of 1950. There are only a few revisions that call for comment. On the other hand, the edition of 1950 contained far more extensive revisions of the first edition, which appeared in 1939 under the title Your Chance to Win. One major revision was required by the appearance in 1953 of a very important work, a life of Cardan,* a brief account of whom is given in Chapter 11. -

Conceptual Human-System Interface Design for a Lunar Access Vehicle

Conceptual Human-System Interface Design for a Lunar Access Vehicle Mary Cummings Enlie Wang Cristin Smith Jessica Marquez Mark Duppen Stephane Essama Massachusetts Institute of Technology* Prepared For Draper Labs Award #: SC001-018 PI: Dava Newman HAL2005-04 September, 2005 http://halab.mit.edu e-mail: [email protected] *MIT Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Cambridge, MA 02139 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................... 1 1.1 THE GENERAL FRAMEWORK................................................................................ 1 1.2 ORGANIZATION.................................................................................................... 2 2 H-SI BACKGROUND AND MOTIVATION ........................................................ 3 2.1 APOLLO VS. LAV H-SI........................................................................................ 3 2.2 APOLLO VS. LUNAR ACCESS REQUIREMENTS ...................................................... 4 3 THE LAV CONCEPTUAL PROTOTYPE............................................................ 5 3.1 HS-I DESIGN ASSUMPTIONS ................................................................................ 5 3.2 THE CONCEPTUAL PROTOTYPE ............................................................................ 6 3.3 LANDING ZONE (LZ) DISPLAY............................................................................. 8 3.3.1 LZ Display Introduction................................................................................. -

Planning a Mission to the Lunar South Pole

Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter: (Diviner) Audience Planning a Mission to Grades 9-10 the Lunar South Pole Time Recommended 1-2 hours AAAS STANDARDS Learning Objectives: • 12A/H1: Exhibit traits such as curiosity, honesty, open- • Learn about recent discoveries in lunar science. ness, and skepticism when making investigations, and value those traits in others. • Deduce information from various sources of scientific data. • 12E/H4: Insist that the key assumptions and reasoning in • Use critical thinking to compare and evaluate different datasets. any argument—whether one’s own or that of others—be • Participate in team-based decision-making. made explicit; analyze the arguments for flawed assump- • Use logical arguments and supporting information to justify decisions. tions, flawed reasoning, or both; and be critical of the claims if any flaws in the argument are found. • 4A/H3: Increasingly sophisticated technology is used Preparation: to learn about the universe. Visual, radio, and X-ray See teacher procedure for any details. telescopes collect information from across the entire spectrum of electromagnetic waves; computers handle Background Information: data and complicated computations to interpret them; space probes send back data and materials from The Moon’s surface thermal environment is among the most extreme of any remote parts of the solar system; and accelerators give planetary body in the solar system. With no atmosphere to store heat or filter subatomic particles energies that simulate conditions in the Sun’s radiation, midday temperatures on the Moon’s surface can reach the stars and in the early history of the universe before 127°C (hotter than boiling water) whereas at night they can fall as low as stars formed. -

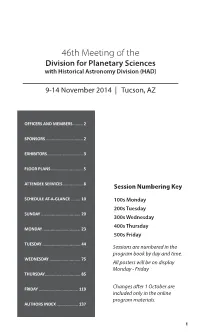

PDF Program Book

46th Meeting of the Division for Planetary Sciences with Historical Astronomy Division (HAD) 9-14 November 2014 | Tucson, AZ OFFICERS AND MEMBERS ........ 2 SPONSORS ............................... 2 EXHIBITORS .............................. 3 FLOOR PLANS ........................... 5 ATTENDEE SERVICES ................. 8 Session Numbering Key SCHEDULE AT-A-GLANCE ........ 10 100s Monday 200s Tuesday SUNDAY ................................. 20 300s Wednesday 400s Thursday MONDAY ................................ 23 500s Friday TUESDAY ................................ 44 Sessions are numbered in the program book by day and time. WEDNESDAY .......................... 75 All posters will be on display Monday - Friday THURSDAY.............................. 85 FRIDAY ................................. 119 Changes after 1 October are included only in the online program materials. AUTHORS INDEX .................. 137 1 DPS OFFICERS AND MEMBERS Current DPS Officers Heidi Hammel Chair Bonnie Buratti Vice-Chair Athena Coustenis Secretary Andrew Rivkin Treasurer Nick Schneider Education and Public Outreach Officer Vishnu Reddy Press Officer Current DPS Committee Members Rosaly Lopes Term Expires November 2014 Robert Pappalardo Term Expires November 2014 Ralph McNutt Term Expires November 2014 Ross Beyer Term Expires November 2015 Paul Withers Term Expires November 2015 Julie Castillo-Rogez Term Expires October 2016 Jani Radebaugh Term Expires October 2016 SPONSORS 2 EXHIBITORS Platinum Exhibitor Silver Exhibitors 3 EXHIBIT BOOTH ASSIGNMENTS 206 Applied