Lunar Impact Basins Revealed by Gravity Recovery and Interior

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LUNAR INTERACTIONS ABSTRACTS of PAPERS PRESENTED at the CONFERENCE on INTERACTIONS of the INTERPLANETARY PLASMA with the MODERN and ANCIENT MOON

LUNAR INTERACTIONS ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS PRESENTED AT THE CONFERENCE ON INTERACTIONS OF THE INTERPLANETARY PLASMA with the MODERN AND ANCIENT MOON ORGANIZED BY THE I. N 3 LUNAR SCIENCE INSTITUTE m I 3 AND THE I- 2 SPACE PHYSICS DEPARTMENT RICE UNIVERSITY sponsored by the NATIONAL AERONAUTICS m m AND 0 .. I-( OIW mrl SPACE ADMINISTRATION ZX CV OH IOI H WclU AND THE uux- V&H 0 NATIONAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION g,,,, wm. WWO@W u u ? ZZLOX€e HW5H vlOHU ffiMHrnfC 4 ffi H 2.~4~4a Edited by 3 dz ,.aV)ffiuJO ffiwcstn WPt.4" DAVID R. CRISWELL ,!a !a Pl r 4 W Pa4 %- rn ZW. and Or=4OcC+J fO Hi4 r WWF I rnU2.M ffiBZ* JOHN W. FREEMAN UUW4aJ I amor 0 alffiwffi E REPRODUCTION RESTRICTIONS OVERRIDDEN 2Z~OZ E 2 2 .: u Bmscientific ma Technical Information FaciLitX -eu $4 to) Copyright O 1974 by the Lunar Science Institute Conference held at George Williams College Lake Geneva Campus Williams Bay, Wisconsin 30 September - 4 October 1974 Compiled by and available from The Lunar Science Institute 3303 Nasa Road 1 Houston, Texas 77058 PREFACE The field of lunar science has essentially completed a period of exponential growth promoted by the national efforts of the 1960's to land on the moon. As normally happens in a diverse scientific community, the interpretations of specialized lunar data have reflected the precepts in the various specialized fields. Constant promotion of the broadest overviews between these diverse fields is appropriate to identify processes or phenomenon recog- nized in one avenue of investigation which may have great importance in explaining the data of other specialities. -

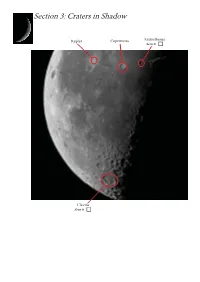

Craters in Shadow

Section 3: Craters in Shadow Kepler Copernicus Eratosthenes Seen it Clavius Seen it Section 3: Craters in Shadow Visibility: A pair of binoculars is the minimum requirement to see these features. When: Look for them when the terminator’s close by, typically a day before last quarter. Not all craters are best seen when the Sun is high in the lunar sky - in fact most aren’t! If craters aren’t par- ticularly bright or dark, they tend to disappear into the background when the Moon’s phase is close to full. These craters are best seen when the ‘terminator’ is nearby, or when the Sun is low in the lunar sky as seen from the crater. This causes oblique lighting to fall on the crater and create exaggerated shadows. Ultimately, this makes the crater look more dramatic and easier to see. We’ll use this effect for the next section on lunar mountains, but before we do, there are a couple of craters that we’d like to bring to your attention. Actually, the Moon is covered with a whole host of wonderful craters that look amazing when the lighting is oblique. During the summer and into the early autumn, it’s the later phases of the Moon are best positioned in the sky - the phases following full Moon. Unfortunately, this means viewing in the early hours but don’t worry as we’ve kept things simple. We just want to give you a taste of what a shadowed crater looks like for this marathon, so the going here is really pretty easy! First, locate the two craters Kepler and Copernicus which were marathon targets pointed out in Section 2. -

LCROSS (Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite) Observation Campaign: Strategies, Implementation, and Lessons Learned

Space Sci Rev DOI 10.1007/s11214-011-9759-y LCROSS (Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite) Observation Campaign: Strategies, Implementation, and Lessons Learned Jennifer L. Heldmann · Anthony Colaprete · Diane H. Wooden · Robert F. Ackermann · David D. Acton · Peter R. Backus · Vanessa Bailey · Jesse G. Ball · William C. Barott · Samantha K. Blair · Marc W. Buie · Shawn Callahan · Nancy J. Chanover · Young-Jun Choi · Al Conrad · Dolores M. Coulson · Kirk B. Crawford · Russell DeHart · Imke de Pater · Michael Disanti · James R. Forster · Reiko Furusho · Tetsuharu Fuse · Tom Geballe · J. Duane Gibson · David Goldstein · Stephen A. Gregory · David J. Gutierrez · Ryan T. Hamilton · Taiga Hamura · David E. Harker · Gerry R. Harp · Junichi Haruyama · Morag Hastie · Yutaka Hayano · Phillip Hinz · Peng K. Hong · Steven P. James · Toshihiko Kadono · Hideyo Kawakita · Michael S. Kelley · Daryl L. Kim · Kosuke Kurosawa · Duk-Hang Lee · Michael Long · Paul G. Lucey · Keith Marach · Anthony C. Matulonis · Richard M. McDermid · Russet McMillan · Charles Miller · Hong-Kyu Moon · Ryosuke Nakamura · Hirotomo Noda · Natsuko Okamura · Lawrence Ong · Dallan Porter · Jeffery J. Puschell · John T. Rayner · J. Jedadiah Rembold · Katherine C. Roth · Richard J. Rudy · Ray W. Russell · Eileen V. Ryan · William H. Ryan · Tomohiko Sekiguchi · Yasuhito Sekine · Mark A. Skinner · Mitsuru Sôma · Andrew W. Stephens · Alex Storrs · Robert M. Suggs · Seiji Sugita · Eon-Chang Sung · Naruhisa Takatoh · Jill C. Tarter · Scott M. Taylor · Hiroshi Terada · Chadwick J. Trujillo · Vidhya Vaitheeswaran · Faith Vilas · Brian D. Walls · Jun-ihi Watanabe · William J. Welch · Charles E. Woodward · Hong-Suh Yim · Eliot F. Young Received: 9 October 2010 / Accepted: 8 February 2011 © The Author(s) 2011. -

Glossary Glossary

Glossary Glossary Albedo A measure of an object’s reflectivity. A pure white reflecting surface has an albedo of 1.0 (100%). A pitch-black, nonreflecting surface has an albedo of 0.0. The Moon is a fairly dark object with a combined albedo of 0.07 (reflecting 7% of the sunlight that falls upon it). The albedo range of the lunar maria is between 0.05 and 0.08. The brighter highlands have an albedo range from 0.09 to 0.15. Anorthosite Rocks rich in the mineral feldspar, making up much of the Moon’s bright highland regions. Aperture The diameter of a telescope’s objective lens or primary mirror. Apogee The point in the Moon’s orbit where it is furthest from the Earth. At apogee, the Moon can reach a maximum distance of 406,700 km from the Earth. Apollo The manned lunar program of the United States. Between July 1969 and December 1972, six Apollo missions landed on the Moon, allowing a total of 12 astronauts to explore its surface. Asteroid A minor planet. A large solid body of rock in orbit around the Sun. Banded crater A crater that displays dusky linear tracts on its inner walls and/or floor. 250 Basalt A dark, fine-grained volcanic rock, low in silicon, with a low viscosity. Basaltic material fills many of the Moon’s major basins, especially on the near side. Glossary Basin A very large circular impact structure (usually comprising multiple concentric rings) that usually displays some degree of flooding with lava. The largest and most conspicuous lava- flooded basins on the Moon are found on the near side, and most are filled to their outer edges with mare basalts. -

Evidence for Thermal-Stress-Induced Rockfalls on Mars Impact Crater Slopes

Icarus 342 (2020) 113503 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Icarus journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/icarus Evidence for thermal-stress-induced rockfalls on Mars impact crater slopes P.-A. Tesson a,b,*, S.J. Conway b, N. Mangold b, J. Ciazela a, S.R. Lewis c, D. M�ege a a Space Research Centre, Polish Academy of Science, Wrocław, Poland b Laboratoire de Plan�etologie et G�eodynamique UMR 6112, CNRS, Nantes, France c School of Physical Sciences, The Open University, Walton Hall, Milton Keynes MK7 6AA, UK ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Here we study rocks falling from exposed outcrops of bedrock, which have left tracks on the slope over which Mars, surface they have bounced and/or rolled, in fresh impact craters (1–10 km in diameter) on Mars. The presence of these Thermal stress tracks shows that these rocks have fallen relatively recently because aeolian processes are known to infill Ices topographic lows over time. Mapping of rockfall tracks indicate trends in frequency with orientation, which in Solar radiation � � turn depend on the latitudinal position of the crater. Craters in the equatorial belt (between 15 N and 15 S) Weathering exhibit higher frequencies of rockfall on their north-south oriented slopes compared to their east-west ones. � Craters >15 N/S have notably higher frequencies on their equator-facing slopes as opposed to the other ori entations. We computed solar radiation on the surface of crater slopes to compare insolation patterns with the spatial distribution of rockfalls, and found statistically significant correlations between maximum diurnal inso lation and rockfall frequency. -

Feature of the Month – January 2016 Galilaei

A PUBLICATION OF THE LUNAR SECTION OF THE A.L.P.O. EDITED BY: Wayne Bailey [email protected] 17 Autumn Lane, Sewell, NJ 08080 RECENT BACK ISSUES: http://moon.scopesandscapes.com/tlo_back.html FEATURE OF THE MONTH – JANUARY 2016 GALILAEI Sketch and text by Robert H. Hays, Jr. - Worth, Illinois, USA October 26, 2015 03:32-03:58 UT, 15 cm refl, 170x, seeing 8-9/10 I sketched this crater and vicinity on the evening of Oct. 25/26, 2015 after the moon hid ZC 109. This was about 32 hours before full. Galilaei is a modest but very crisp crater in far western Oceanus Procellarum. It appears very symmetrical, but there is a faint strip of shadow protruding from its southern end. Galilaei A is the very similar but smaller crater north of Galilaei. The bright spot to the south is labeled Galilaei D on the Lunar Quadrant map. A tiny bit of shadow was glimpsed in this spot indicating a craterlet. Two more moderately bright spots are east of Galilaei. The western one of this pair showed a bit of shadow, much like Galilaei D, but the other one did not. Galilaei B is the shadow-filled crater to the west. This shadowing gave this crater a ring shape. This ring was thicker on its west side. Galilaei H is the small pit just west of B. A wide, low ridge extends to the southwest from Galilaei B, and a crisper peak is south of H. Galilaei B must be more recent than its attendant ridge since the crater's exterior shadow falls upon the ridge. -

Martian Crater Morphology

ANALYSIS OF THE DEPTH-DIAMETER RELATIONSHIP OF MARTIAN CRATERS A Capstone Experience Thesis Presented by Jared Howenstine Completion Date: May 2006 Approved By: Professor M. Darby Dyar, Astronomy Professor Christopher Condit, Geology Professor Judith Young, Astronomy Abstract Title: Analysis of the Depth-Diameter Relationship of Martian Craters Author: Jared Howenstine, Astronomy Approved By: Judith Young, Astronomy Approved By: M. Darby Dyar, Astronomy Approved By: Christopher Condit, Geology CE Type: Departmental Honors Project Using a gridded version of maritan topography with the computer program Gridview, this project studied the depth-diameter relationship of martian impact craters. The work encompasses 361 profiles of impacts with diameters larger than 15 kilometers and is a continuation of work that was started at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston, Texas under the guidance of Dr. Walter S. Keifer. Using the most ‘pristine,’ or deepest craters in the data a depth-diameter relationship was determined: d = 0.610D 0.327 , where d is the depth of the crater and D is the diameter of the crater, both in kilometers. This relationship can then be used to estimate the theoretical depth of any impact radius, and therefore can be used to estimate the pristine shape of the crater. With a depth-diameter ratio for a particular crater, the measured depth can then be compared to this theoretical value and an estimate of the amount of material within the crater, or fill, can then be calculated. The data includes 140 named impact craters, 3 basins, and 218 other impacts. The named data encompasses all named impact structures of greater than 100 kilometers in diameter. -

Ignimbrites to Batholiths Ignimbrites to Batholiths: Integrating Perspectives from Geological, Geophysical, and Geochronological Data

Ignimbrites to batholiths Ignimbrites to batholiths: Integrating perspectives from geological, geophysical, and geochronological data Peter W. Lipman1,* and Olivier Bachmann2 1U.S. Geological Survey, Mail Stop 910, Menlo Park, California 94028, USA 2Institute of Geochemistry and Petrology, ETH Zurich, CH-8092 Zürich, Switzerland ABSTRACT related intrusions cooled and solidified soon shorter. Magma-supply estimates (from ages after zircon crystallization, as magma sup- and volcano-plutonic volumes) yield focused Multistage histories of incremental accu- ply waned. Some researchers interpret these intrusion-assembly rates sufficient to gener- mulation, fractionation, and solidification results as recording pluton assembly in small ate ignimbrite-scale volumes of eruptible during construction of large subvolcanic increments that crystallized rapidly, leading magma, based on published thermal models. magma bodies that remained sufficiently to temporal disconnects between ignimbrite Mid-Tertiary processes of batholith assembly liquid to erupt are recorded by Tertiary eruption and intrusion growth. Alternatively, associated with the SRMVF caused drastic ignimbrites, source calderas, and granitoid crystallization ages of the granitic rocks chemical and physical reconstruction of the intrusions associated with large gravity lows are here inferred to record late solidifica- entire lithosphere, probably accompanied by at the Southern Rocky Mountain volcanic tion, after protracted open-system evolution asthenospheric input. field (SRMVF). Geophysical -

Warfare in a Fragile World: Military Impact on the Human Environment

Recent Slprt•• books World Armaments and Disarmament: SIPRI Yearbook 1979 World Armaments and Disarmament: SIPRI Yearbooks 1968-1979, Cumulative Index Nuclear Energy and Nuclear Weapon Proliferation Other related •• 8lprt books Ecological Consequences of the Second Ihdochina War Weapons of Mass Destruction and the Environment Publish~d on behalf of SIPRI by Taylor & Francis Ltd 10-14 Macklin Street London WC2B 5NF Distributed in the USA by Crane, Russak & Company Inc 3 East 44th Street New York NY 10017 USA and in Scandinavia by Almqvist & WikseH International PO Box 62 S-101 20 Stockholm Sweden For a complete list of SIPRI publications write to SIPRI Sveavagen 166 , S-113 46 Stockholm Sweden Stoekholol International Peace Research Institute Warfare in a Fragile World Military Impact onthe Human Environment Stockholm International Peace Research Institute SIPRI is an independent institute for research into problems of peace and conflict, especially those of disarmament and arms regulation. It was established in 1966 to commemorate Sweden's 150 years of unbroken peace. The Institute is financed by the Swedish Parliament. The staff, the Governing Board and the Scientific Council are international. As a consultative body, the Scientific Council is not responsible for the views expressed in the publications of the Institute. Governing Board Dr Rolf Bjornerstedt, Chairman (Sweden) Professor Robert Neild, Vice-Chairman (United Kingdom) Mr Tim Greve (Norway) Academician Ivan M£ilek (Czechoslovakia) Professor Leo Mates (Yugoslavia) Professor -

Sky and Telescope

SkyandTelescope.com The Lunar 100 By Charles A. Wood Just about every telescope user is familiar with French comet hunter Charles Messier's catalog of fuzzy objects. Messier's 18th-century listing of 109 galaxies, clusters, and nebulae contains some of the largest, brightest, and most visually interesting deep-sky treasures visible from the Northern Hemisphere. Little wonder that observing all the M objects is regarded as a virtual rite of passage for amateur astronomers. But the night sky offers an object that is larger, brighter, and more visually captivating than anything on Messier's list: the Moon. Yet many backyard astronomers never go beyond the astro-tourist stage to acquire the knowledge and understanding necessary to really appreciate what they're looking at, and how magnificent and amazing it truly is. Perhaps this is because after they identify a few of the Moon's most conspicuous features, many amateurs don't know where Many Lunar 100 selections are plainly visible in this image of the full Moon, while others require to look next. a more detailed view, different illumination, or favorable libration. North is up. S&T: Gary The Lunar 100 list is an attempt to provide Moon lovers with Seronik something akin to what deep-sky observers enjoy with the Messier catalog: a selection of telescopic sights to ignite interest and enhance understanding. Presented here is a selection of the Moon's 100 most interesting regions, craters, basins, mountains, rilles, and domes. I challenge observers to find and observe them all and, more important, to consider what each feature tells us about lunar and Earth history. -

Planning a Mission to the Lunar South Pole

Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter: (Diviner) Audience Planning a Mission to Grades 9-10 the Lunar South Pole Time Recommended 1-2 hours AAAS STANDARDS Learning Objectives: • 12A/H1: Exhibit traits such as curiosity, honesty, open- • Learn about recent discoveries in lunar science. ness, and skepticism when making investigations, and value those traits in others. • Deduce information from various sources of scientific data. • 12E/H4: Insist that the key assumptions and reasoning in • Use critical thinking to compare and evaluate different datasets. any argument—whether one’s own or that of others—be • Participate in team-based decision-making. made explicit; analyze the arguments for flawed assump- • Use logical arguments and supporting information to justify decisions. tions, flawed reasoning, or both; and be critical of the claims if any flaws in the argument are found. • 4A/H3: Increasingly sophisticated technology is used Preparation: to learn about the universe. Visual, radio, and X-ray See teacher procedure for any details. telescopes collect information from across the entire spectrum of electromagnetic waves; computers handle Background Information: data and complicated computations to interpret them; space probes send back data and materials from The Moon’s surface thermal environment is among the most extreme of any remote parts of the solar system; and accelerators give planetary body in the solar system. With no atmosphere to store heat or filter subatomic particles energies that simulate conditions in the Sun’s radiation, midday temperatures on the Moon’s surface can reach the stars and in the early history of the universe before 127°C (hotter than boiling water) whereas at night they can fall as low as stars formed. -

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title Astrophysics in 2006 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5760h9v8 Journal Space Science Reviews, 132(1) ISSN 0038-6308 Authors Trimble, V Aschwanden, MJ Hansen, CJ Publication Date 2007-09-01 DOI 10.1007/s11214-007-9224-0 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Space Sci Rev (2007) 132: 1–182 DOI 10.1007/s11214-007-9224-0 Astrophysics in 2006 Virginia Trimble · Markus J. Aschwanden · Carl J. Hansen Received: 11 May 2007 / Accepted: 24 May 2007 / Published online: 23 October 2007 © Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2007 Abstract The fastest pulsar and the slowest nova; the oldest galaxies and the youngest stars; the weirdest life forms and the commonest dwarfs; the highest energy particles and the lowest energy photons. These were some of the extremes of Astrophysics 2006. We attempt also to bring you updates on things of which there is currently only one (habitable planets, the Sun, and the Universe) and others of which there are always many, like meteors and molecules, black holes and binaries. Keywords Cosmology: general · Galaxies: general · ISM: general · Stars: general · Sun: general · Planets and satellites: general · Astrobiology · Star clusters · Binary stars · Clusters of galaxies · Gamma-ray bursts · Milky Way · Earth · Active galaxies · Supernovae 1 Introduction Astrophysics in 2006 modifies a long tradition by moving to a new journal, which you hold in your (real or virtual) hands. The fifteen previous articles in the series are referenced oc- casionally as Ap91 to Ap05 below and appeared in volumes 104–118 of Publications of V.