Craters in Shadow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sky and Telescope

SkyandTelescope.com The Lunar 100 By Charles A. Wood Just about every telescope user is familiar with French comet hunter Charles Messier's catalog of fuzzy objects. Messier's 18th-century listing of 109 galaxies, clusters, and nebulae contains some of the largest, brightest, and most visually interesting deep-sky treasures visible from the Northern Hemisphere. Little wonder that observing all the M objects is regarded as a virtual rite of passage for amateur astronomers. But the night sky offers an object that is larger, brighter, and more visually captivating than anything on Messier's list: the Moon. Yet many backyard astronomers never go beyond the astro-tourist stage to acquire the knowledge and understanding necessary to really appreciate what they're looking at, and how magnificent and amazing it truly is. Perhaps this is because after they identify a few of the Moon's most conspicuous features, many amateurs don't know where Many Lunar 100 selections are plainly visible in this image of the full Moon, while others require to look next. a more detailed view, different illumination, or favorable libration. North is up. S&T: Gary The Lunar 100 list is an attempt to provide Moon lovers with Seronik something akin to what deep-sky observers enjoy with the Messier catalog: a selection of telescopic sights to ignite interest and enhance understanding. Presented here is a selection of the Moon's 100 most interesting regions, craters, basins, mountains, rilles, and domes. I challenge observers to find and observe them all and, more important, to consider what each feature tells us about lunar and Earth history. -

Pete Aldridge Well, Good Afternoon, Ladies and Gentlemen, and Welcome to the Fifth and Final Public Hearing of the President’S Commission on Moon, Mars, and Beyond

The President’s Commission on Implementation of United States Space Exploration Policy PUBLIC HEARING Asia Society 725 Park Avenue New York, NY Monday, May 3, and Tuesday, May 4, 2004 Pete Aldridge Well, good afternoon, ladies and gentlemen, and welcome to the fifth and final public hearing of the President’s Commission on Moon, Mars, and Beyond. I think I can speak for everyone here when I say that the time period since this Commission was appointed and asked to produce a report has elapsed at the speed of light. At least it seems that way. Since February, we’ve heard testimonies from a broad range of space experts, the Mars rovers have won an expanded audience of space enthusiasts, and a renewed interest in space science has surfaced, calling for a new generation of space educators. In less than a month, we will present our findings to the White House. The Commission is here to explore ways to achieve the President’s vision of going back to the Moon and on to Mars and beyond. We have listened and talked to experts at four previous hearings—in Washington, D.C.; Dayton, Ohio; Atlanta, Georgia; and San Francisco, California—and talked among ourselves and we realize that this vision produces a focus not just for NASA but a focus that can revitalize US space capability and have a significant impact on our nation’s industrial base, and academia, and the quality of life for all Americans. As you can see from our agenda, we’re talking with those experts from many, many disciplines, including those outside the traditional aerospace arena. -

List of Missions Using SPICE (PDF)

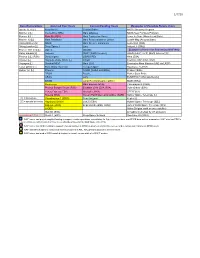

1/7/20 Data Restorations Selected Past Users Current/Pending Users Examples of Possible Future Users Apollo 15, 16 [L] Magellan [L] Cassini Orbiter NASA Discovery Program Mariner 2 [L] Clementine (NRL) Mars Odyssey NASA New Frontiers Program Mariner 9 [L] Mars 96 (RSA) Mars Exploration Rover Lunar IceCube (Moorehead State) Mariner 10 [L] Mars Pathfinder Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter LunaH-Map (Arizona State) Viking Orbiters [L] NEAR Mars Science Laboratory Luna-Glob (RSA) Viking Landers [L] Deep Space 1 Juno Aditya-L1 (ISRO) Pioneer 10/11/12 [L] Galileo MAVEN Examples of Users not Requesting NAIF Help Haley armada [L] Genesis SMAP (Earth Science) GOLD (LASP, UCF) (Earth Science) [L] Phobos 2 [L] (RSA) Deep Impact OSIRIS REx Hera (ESA) Ulysses [L] Huygens Probe (ESA) [L] InSight ExoMars RSP (ESA, RSA) Voyagers [L] Stardust/NExT Mars 2020 Emmirates Mars Mission (UAE via LASP) Lunar Orbiter [L] Mars Global Surveyor Europa Clipper Hayabusa-2 (JAXA) Helios 1,2 [L] Phoenix NISAR (NASA and ISRO) Proba-3 (ESA) EPOXI Psyche Parker Solar Probe GRAIL Lucy EUMETSAT GEO satellites [L] DAWN Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter MOM (ISRO) Messenger Mars Express (ESA) Chandrayan-2 (ISRO) Phobos Sample Return (RSA) ExoMars 2016 (ESA, RSA) Solar Orbiter (ESA) Venus Express (ESA) Akatsuki (JAXA) STEREO [L] Rosetta (ESA) Korean Pathfinder Lunar Orbiter (KARI) Spitzer Space Telescope [L] [L] = limited use Chandrayaan-1 (ISRO) New Horizons Kepler [L] [S] = special services Hayabusa (JAXA) JUICE (ESA) Hubble Space Telescope [S][L] Kaguya (JAXA) Bepicolombo (ESA, JAXA) James Webb Space Telescope [S][L] LADEE Altius (Belgian earth science satellite) ISO [S] (ESA) Armadillo (CubeSat, by UT at Austin) Last updated: 1/7/20 Smart-1 (ESA) Deep Space Network Spectrum-RG (RSA) NAIF has or had project-supplied funding to support mission operations, consultation for flight team members, and SPICE data archive preparation. -

10Great Features for Moon Watchers

Sinus Aestuum is a lava pond hemming the Imbrium debris. Mare Orientale is another of the Moon’s large impact basins, Beginning observing On its eastern edge, dark volcanic material erupted explosively and possibly the youngest. Lunar scientists think it formed 170 along a rille. Although this region at first appears featureless, million years after Mare Imbrium. And although “Mare Orien- observe it at several different lunar phases and you’ll see the tale” translates to “Eastern Sea,” in 1961, the International dark area grow more apparent as the Sun climbs higher. Astronomical Union changed the way astronomers denote great features for Occupying a region below and a bit left of the Moon’s dead lunar directions. The result is that Mare Orientale now sits on center, Mare Nubium lies far from many lunar showpiece sites. the Moon’s western limb. From Earth we never see most of it. Look for it as the dark region above magnificent Tycho Crater. When you observe the Cauchy Domes, you’ll be looking at Yet this small region, where lava plains meet highlands, con- shield volcanoes that erupted from lunar vents. The lava cooled Moon watchers tains a variety of interesting geologic features — impact craters, slowly, so it had a chance to spread and form gentle slopes. 10Our natural satellite offers plenty of targets you can spot through any size telescope. lava-flooded plains, tectonic faulting, and debris from distant In a geologic sense, our Moon is now quiet. The only events by Michael E. Bakich impacts — that are great for telescopic exploring. -

Planetary Science : a Lunar Perspective

APPENDICES APPENDIX I Reference Abbreviations AJS: American Journal of Science Ancient Sun: The Ancient Sun: Fossil Record in the Earth, Moon and Meteorites (Eds. R. 0.Pepin, et al.), Pergamon Press (1980) Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta Suppl. 13 Ap. J.: Astrophysical Journal Apollo 15: The Apollo 1.5 Lunar Samples, Lunar Science Insti- tute, Houston, Texas (1972) Apollo 16 Workshop: Workshop on Apollo 16, LPI Technical Report 81- 01, Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston (1981) Basaltic Volcanism: Basaltic Volcanism on the Terrestrial Planets, Per- gamon Press (1981) Bull. GSA: Bulletin of the Geological Society of America EOS: EOS, Transactions of the American Geophysical Union EPSL: Earth and Planetary Science Letters GCA: Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta GRL: Geophysical Research Letters Impact Cratering: Impact and Explosion Cratering (Eds. D. J. Roddy, et al.), 1301 pp., Pergamon Press (1977) JGR: Journal of Geophysical Research LS 111: Lunar Science III (Lunar Science Institute) see extended abstract of Lunar Science Conferences Appendix I1 LS IV: Lunar Science IV (Lunar Science Institute) LS V: Lunar Science V (Lunar Science Institute) LS VI: Lunar Science VI (Lunar Science Institute) LS VII: Lunar Science VII (Lunar Science Institute) LS VIII: Lunar Science VIII (Lunar Science Institute LPS IX: Lunar and Planetary Science IX (Lunar and Plane- tary Institute LPS X: Lunar and Planetary Science X (Lunar and Plane- tary Institute) LPS XI: Lunar and Planetary Science XI (Lunar and Plane- tary Institute) LPS XII: Lunar and Planetary Science XII (Lunar and Planetary Institute) 444 Appendix I Lunar Highlands Crust: Proceedings of the Conference in the Lunar High- lands Crust, 505 pp., Pergamon Press (1980) Geo- chim. -

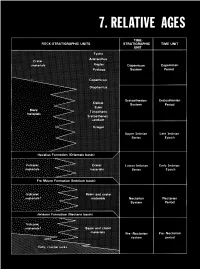

Relative Ages

CONTENTS Page Introduction ...................................................... 123 Stratigraphic nomenclature ........................................ 123 Superpositions ................................................... 125 Mare-crater relations .......................................... 125 Crater-crater relations .......................................... 127 Basin-crater relations .......................................... 127 Mapping conventions .......................................... 127 Crater dating .................................................... 129 General principles ............................................. 129 Size-frequency relations ........................................ 129 Morphology of large craters .................................... 129 Morphology of small craters, by Newell J. Fask .................. 131 D, method .................................................... 133 Summary ........................................................ 133 table 7.1). The first three of these sequences, which are older than INTRODUCTION the visible mare materials, are also dominated internally by the The goals of both terrestrial and lunar stratigraphy are to inte- deposits of basins. The fourth (youngest) sequence consists of mare grate geologic units into a stratigraphic column applicable over the and crater materials. This chapter explains the general methods of whole planet and to calibrate this column with absolute ages. The stratigraphic analysis that are employed in the next six chapters first step in reconstructing -

Astrophysics

National Aeronautics and Space Administration Astrophysics Committee on NASA Science Paul Hertz Mission Extensions Director, Astrophysics Division NRC Keck Center Science Mission Directorate Washington DC @PHertzNASA February 1-2, 2016 Why Astrophysics? Astrophysics is humankind’s scientific endeavor to understand the universe and our place in it. 1. How did our universe 2. How did galaxies, stars, 3. Are We Alone? begin and evolve? and planets come to be? These national strategic drivers are enduring 1972 1982 1991 2001 2010 2 Astrophysics Driving Documents http://science.nasa.gov/astrophysics/documents 3 Astrophysics Programs Physics of the Cosmos Cosmic Origins Exoplanet Exploration Program Program Program 1. How did our universe 2. How did galaxies, stars, 3. Are We Alone? begin and evolve? and planets come to be? Astrophysics Explorers Program Astrophysics Research Program James Webb Space Telescope Program (managed outside of Astrophysics Division until commissioning) 4 Astrophysics Programs and Missions Physics of the Cosmos Cosmic Origins Exoplanet Exploration Program Program Program Chandra Hubble Spitzer Kepler/K2 XMM-Newton (ESA) Herschel (ESA) WFIRST Fermi SOFIA Planck (ESA) LISA Pathfinder (ESA) Astrophysics Explorers Program Euclid (ESA) NuSTAR Swift Suzaku (JAXA) Athena (ESA) ASTRO-H (JAXA) NICER TESS L3 GW Obs (ESA) 3 SMEX and 2 MO in Phase A James Webb Space Telescope Program: Webb 5 Astrophysics Programs and Missions Physics of the Cosmos Cosmic Origins Exoplanet Exploration Program Program Program Missions in extended phase Chandra Hubble Spitzer Kepler/K2 XMM-Newton (ESA) Herschel (ESA) WFIRST Fermi SOFIA Planck (ESA) LISA Pathfinder (ESA) Astrophysics Explorers Program Euclid (ESA) NuSTAR Swift Suzaku (JAXA) Athena (ESA) ASTRO-H (JAXA) NICER TESS L3 GW Obs (ESA) 3 SMEX and 2 MO in Phase A James Webb Space Telescope Program: Webb 6 Astrophysics Mission Portfolio • NASA Astrophysics seeks to advance NASA’s strategic objectives in astrophysics as well as the science priorities of the Decadal Survey in Astronomy and Astrophysics. -

Explore 12 Great Lunar Targets Sharpen Your Observing Skills on the Moon’S Craters, Lava Flows, and an Elusive Letter X

Small-scope wonders 11 7 Explore 12 great lunar targets Sharpen your observing skills on the Moon’s craters, lava flows, and an elusive letter X. 2 1 by Michael E. Bakich he Moon offers something for every observer. It has a face that’s always changing. Following it telescopically T through a lunar month can be fascinating. Ironically, when the Moon is brightest (Full Moon) is the worst time to view it. From our perspective, the Sun is shining on the Moon from a point directly behind us, minimizing shad- ows and thus revealing scant detail. 4 The best lunar viewing times are from when the thin cres- 5 cent becomes visible after New Moon until about 2 days after First Quarter (evening sky) and from about 2 days before Last Quarter to almost New Moon (morning sky). Shadows are lon- ger then, and features stand out in sharp relief. 8 This is especially true along the Moon’s shadow line — called the terminator — which divides the light and dark portions. Before Full Moon, the terminator shows where sunrise is occur- 12 ring; after Full Moon, it marks the sunset line. 6 10 Along the terminator, you’ll see mountaintops protruding high enough to catch sunlight while the dark lower terrain sur- rounds them. On large crater floors, you can follow “wall shad- ows” cast by sides of craters hundreds of feet high. All these 1 Archimedes Crater lies at 30° north latitude centered between the features seem to change in real time, and the differences you eastern and western limbs. -

Slaves, Sex, and Transgression in Greek Old Comedy

Slaves, Sex, and Transgression in Greek Old Comedy By Daniel Christopher Walin A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Classics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Mark Griffith, Chair Professor Donald J. Mastronarde Professor Kathleen McCarthy Professor Emily Mackil Spring 2012 1 Abstract Slaves, Sex, and Transgression in Greek Old Comedy by Daniel Christopher Walin Doctor of Philosophy in Classics University of California, Berkeley Professor Mark Griffith, Chair This dissertation examines the often surprising role of the slave characters of Greek Old Comedy in sexual humor, building on work I began in my 2009 Classical Quarterly article ("An Aristophanic Slave: Peace 819–1126"). The slave characters of New and Roman comedy have long been the subject of productive scholarly interest; slave characters in Old Comedy, by contrast, have received relatively little attention (the sole extensive study being Stefanis 1980). Yet a closer look at the ancestors of the later, more familiar comic slaves offers new perspectives on Greek attitudes toward sex and social status, as well as what an Athenian audience expected from and enjoyed in Old Comedy. Moreover, my arguments about how to read several passages involving slave characters, if accepted, will have larger implications for our interpretation of individual plays. The first chapter sets the stage for the discussion of "sexually presumptive" slave characters by treating the idea of sexual relations between slaves and free women in Greek literature generally and Old Comedy in particular. I first examine the various (non-comic) treatments of this theme in Greek historiography, then its exploitation for comic effect in the fifth mimiamb of Herodas and in Machon's Chreiai. -

Water on the Moon, III. Volatiles & Activity

Water on The Moon, III. Volatiles & Activity Arlin Crotts (Columbia University) For centuries some scientists have argued that there is activity on the Moon (or water, as recounted in Parts I & II), while others have thought the Moon is simply a dead, inactive world. [1] The question comes in several forms: is there a detectable atmosphere? Does the surface of the Moon change? What causes interior seismic activity? From a more modern viewpoint, we now know that as much carbon monoxide as water was excavated during the LCROSS impact, as detailed in Part I, and a comparable amount of other volatiles were found. At one time the Moon outgassed prodigious amounts of water and hydrogen in volcanic fire fountains, but released similar amounts of volatile sulfur (or SO2), and presumably large amounts of carbon dioxide or monoxide, if theory is to be believed. So water on the Moon is associated with other gases. Astronomers have agreed for centuries that there is no firm evidence for “weather” on the Moon visible from Earth, and little evidence of thick atmosphere. [2] How would one detect the Moon’s atmosphere from Earth? An obvious means is atmospheric refraction. As you watch the Sun set, its image is displaced by Earth’s atmospheric refraction at the horizon from the position it would have if there were no atmosphere, by roughly 0.6 degree (a bit more than the Sun’s angular diameter). On the Moon, any atmosphere would cause an analogous effect for a star passing behind the Moon during an occultation (multiplied by two since the light travels both into and out of the lunar atmosphere). -

Glossary of Lunar Terminology

Glossary of Lunar Terminology albedo A measure of the reflectivity of the Moon's gabbro A coarse crystalline rock, often found in the visible surface. The Moon's albedo averages 0.07, which lunar highlands, containing plagioclase and pyroxene. means that its surface reflects, on average, 7% of the Anorthositic gabbros contain 65-78% calcium feldspar. light falling on it. gardening The process by which the Moon's surface is anorthosite A coarse-grained rock, largely composed of mixed with deeper layers, mainly as a result of meteor calcium feldspar, common on the Moon. itic bombardment. basalt A type of fine-grained volcanic rock containing ghost crater (ruined crater) The faint outline that remains the minerals pyroxene and plagioclase (calcium of a lunar crater that has been largely erased by some feldspar). Mare basalts are rich in iron and titanium, later action, usually lava flooding. while highland basalts are high in aluminum. glacis A gently sloping bank; an old term for the outer breccia A rock composed of a matrix oflarger, angular slope of a crater's walls. stony fragments and a finer, binding component. graben A sunken area between faults. caldera A type of volcanic crater formed primarily by a highlands The Moon's lighter-colored regions, which sinking of its floor rather than by the ejection of lava. are higher than their surroundings and thus not central peak A mountainous landform at or near the covered by dark lavas. Most highland features are the center of certain lunar craters, possibly formed by an rims or central peaks of impact sites. -

Issue #1 – 2012 October

TTSIQ #1 page 1 OCTOBER 2012 Introducing a new free quarterly newsletter for space-interested and space-enthused people around the globe This free publication is especially dedicated to students and teachers interested in space NEWS SECTION pp. 3-22 p. 3 Earth Orbit and Mission to Planet Earth - 13 reports p. 8 Cislunar Space and the Moon - 5 reports p. 11 Mars and the Asteroids - 5 reports p. 15 Other Planets and Moons - 2 reports p. 17 Starbound - 4 reports, 1 article ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ARTICLES, ESSAYS & MORE pp. 23-45 - 10 articles & essays (full list on last page) ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- STUDENTS & TEACHERS pp. 46-56 - 9 articles & essays (full list on last page) L: Remote sensing of Aerosol Optical Depth over India R: Curiosity finds rocks shaped by running water on Mars! L: China hopes to put lander on the Moon in 2013 R: First Square Kilometer Array telescopes online in Australia! 1 TTSIQ #1 page 2 OCTOBER 2012 TTSIQ Sponsor Organizations 1. About The National Space Society - http://www.nss.org/ The National Space Society was formed in March, 1987 by the merger of the former L5 Society and National Space institute. NSS has an extensive chapter network in the United States and a number of international chapters in Europe, Asia, and Australia. NSS hosts the annual International Space Development Conference in May each year at varying locations. NSS publishes Ad Astra magazine quarterly. NSS actively tries to influence US Space Policy. About The Moon Society - http://www.moonsociety.org The Moon Society was formed in 2000 and seeks to inspire and involve people everywhere in exploration of the Moon with the establishment of civilian settlements, using local resources through private enterprise both to support themselves and to help alleviate Earth's stubborn energy and environmental problems.