Explore 12 Great Lunar Targets Sharpen Your Observing Skills on the Moon’S Craters, Lava Flows, and an Elusive Letter X

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

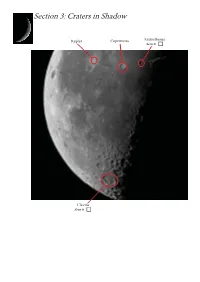

Craters in Shadow

Section 3: Craters in Shadow Kepler Copernicus Eratosthenes Seen it Clavius Seen it Section 3: Craters in Shadow Visibility: A pair of binoculars is the minimum requirement to see these features. When: Look for them when the terminator’s close by, typically a day before last quarter. Not all craters are best seen when the Sun is high in the lunar sky - in fact most aren’t! If craters aren’t par- ticularly bright or dark, they tend to disappear into the background when the Moon’s phase is close to full. These craters are best seen when the ‘terminator’ is nearby, or when the Sun is low in the lunar sky as seen from the crater. This causes oblique lighting to fall on the crater and create exaggerated shadows. Ultimately, this makes the crater look more dramatic and easier to see. We’ll use this effect for the next section on lunar mountains, but before we do, there are a couple of craters that we’d like to bring to your attention. Actually, the Moon is covered with a whole host of wonderful craters that look amazing when the lighting is oblique. During the summer and into the early autumn, it’s the later phases of the Moon are best positioned in the sky - the phases following full Moon. Unfortunately, this means viewing in the early hours but don’t worry as we’ve kept things simple. We just want to give you a taste of what a shadowed crater looks like for this marathon, so the going here is really pretty easy! First, locate the two craters Kepler and Copernicus which were marathon targets pointed out in Section 2. -

Glossary Glossary

Glossary Glossary Albedo A measure of an object’s reflectivity. A pure white reflecting surface has an albedo of 1.0 (100%). A pitch-black, nonreflecting surface has an albedo of 0.0. The Moon is a fairly dark object with a combined albedo of 0.07 (reflecting 7% of the sunlight that falls upon it). The albedo range of the lunar maria is between 0.05 and 0.08. The brighter highlands have an albedo range from 0.09 to 0.15. Anorthosite Rocks rich in the mineral feldspar, making up much of the Moon’s bright highland regions. Aperture The diameter of a telescope’s objective lens or primary mirror. Apogee The point in the Moon’s orbit where it is furthest from the Earth. At apogee, the Moon can reach a maximum distance of 406,700 km from the Earth. Apollo The manned lunar program of the United States. Between July 1969 and December 1972, six Apollo missions landed on the Moon, allowing a total of 12 astronauts to explore its surface. Asteroid A minor planet. A large solid body of rock in orbit around the Sun. Banded crater A crater that displays dusky linear tracts on its inner walls and/or floor. 250 Basalt A dark, fine-grained volcanic rock, low in silicon, with a low viscosity. Basaltic material fills many of the Moon’s major basins, especially on the near side. Glossary Basin A very large circular impact structure (usually comprising multiple concentric rings) that usually displays some degree of flooding with lava. The largest and most conspicuous lava- flooded basins on the Moon are found on the near side, and most are filled to their outer edges with mare basalts. -

8.5 X 13.5 Doublelines.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-74128-6 - Exploring the Solar System with Binoculars: A Beginner’s Guide to the Sun, Moon, and Planets Stephen James O’Meara’s Index More information Index Adams, John Couch, 96 Carrington, Richard C., 15 degree of condensation (DC) of, Agesinax, 24 Carroll, Lewis, 60 111–112 Aionwantha (Hiawatha), 45 Ceres, 70, 99–101 estimating the brightness of, Airy, George Biddell, 50, 51, 55 discovery and history as a planet, 111–112 Alcock, George, 116 99–100 In–Out method, 111 Allen, Richard Hinckley, 136 general description of, 99, Modified–Out method, 111–112 Alphonsus VI (King of Portugal), 104 100–101 experience helps in observing, 112 Andersen, Hans Christian, 92 how to find, 101 flaring in brightness, 111 Arago, Francois, 59 Chaikin, Andrew, 54 how to locate and identify, 110 Araki, Genichi, 116 Challis, James, 50 in history, relating to, 103–108 Arend, Silvio, 115 Chambers, George F., 8, 19 King David, 103 Aristotle, 65 Cheshire Cat, 60 Melville’s Moby-Dick, 107–108 Arlt, Rainer, 132 Children of God (cult), 108 Napoleon, 106 Arrehenius, Svente, 78, 79 Chinese Catalogue (Biot’s), 131–132 Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, 103–104 Arter, T. R., 131 Cicero (Roman emperor), 77 the broadside of the comets of Asteroid Belt, 101 City of God, The, 90 1680 and 1682, 104 brightest objects in, 101–102 Collins, Peter, 116 the death of Julius Caesar, 104 asteroids Cometographia, 103 the Middle Ages, 104 2003 EH1, 131 comets, 103–117 the Old Testament?, 103 3200 Phaeton, 142 1P (Halley), 103, 109, 114–115, the whaling ship -

Sky and Telescope

SkyandTelescope.com The Lunar 100 By Charles A. Wood Just about every telescope user is familiar with French comet hunter Charles Messier's catalog of fuzzy objects. Messier's 18th-century listing of 109 galaxies, clusters, and nebulae contains some of the largest, brightest, and most visually interesting deep-sky treasures visible from the Northern Hemisphere. Little wonder that observing all the M objects is regarded as a virtual rite of passage for amateur astronomers. But the night sky offers an object that is larger, brighter, and more visually captivating than anything on Messier's list: the Moon. Yet many backyard astronomers never go beyond the astro-tourist stage to acquire the knowledge and understanding necessary to really appreciate what they're looking at, and how magnificent and amazing it truly is. Perhaps this is because after they identify a few of the Moon's most conspicuous features, many amateurs don't know where Many Lunar 100 selections are plainly visible in this image of the full Moon, while others require to look next. a more detailed view, different illumination, or favorable libration. North is up. S&T: Gary The Lunar 100 list is an attempt to provide Moon lovers with Seronik something akin to what deep-sky observers enjoy with the Messier catalog: a selection of telescopic sights to ignite interest and enhance understanding. Presented here is a selection of the Moon's 100 most interesting regions, craters, basins, mountains, rilles, and domes. I challenge observers to find and observe them all and, more important, to consider what each feature tells us about lunar and Earth history. -

Pete Aldridge Well, Good Afternoon, Ladies and Gentlemen, and Welcome to the Fifth and Final Public Hearing of the President’S Commission on Moon, Mars, and Beyond

The President’s Commission on Implementation of United States Space Exploration Policy PUBLIC HEARING Asia Society 725 Park Avenue New York, NY Monday, May 3, and Tuesday, May 4, 2004 Pete Aldridge Well, good afternoon, ladies and gentlemen, and welcome to the fifth and final public hearing of the President’s Commission on Moon, Mars, and Beyond. I think I can speak for everyone here when I say that the time period since this Commission was appointed and asked to produce a report has elapsed at the speed of light. At least it seems that way. Since February, we’ve heard testimonies from a broad range of space experts, the Mars rovers have won an expanded audience of space enthusiasts, and a renewed interest in space science has surfaced, calling for a new generation of space educators. In less than a month, we will present our findings to the White House. The Commission is here to explore ways to achieve the President’s vision of going back to the Moon and on to Mars and beyond. We have listened and talked to experts at four previous hearings—in Washington, D.C.; Dayton, Ohio; Atlanta, Georgia; and San Francisco, California—and talked among ourselves and we realize that this vision produces a focus not just for NASA but a focus that can revitalize US space capability and have a significant impact on our nation’s industrial base, and academia, and the quality of life for all Americans. As you can see from our agenda, we’re talking with those experts from many, many disciplines, including those outside the traditional aerospace arena. -

JRASC-2007-04-Hr.Pdf

Publications and Products of April / avril 2007 Volume/volume 101 Number/numéro 2 [723] The Royal Astronomical Society of Canada Observer’s Calendar — 2007 The award-winning RASC Observer's Calendar is your annual guide Created by the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada and richly illustrated by photographs from leading amateur astronomers, the calendar pages are packed with detailed information including major lunar and planetary conjunctions, The Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada Le Journal de la Société royale d’astronomie du Canada meteor showers, eclipses, lunar phases, and daily Moonrise and Moonset times. Canadian and U.S. holidays are highlighted. Perfect for home, office, or observatory. Individual Order Prices: $16.95 Cdn/ $13.95 US RASC members receive a $3.00 discount Shipping and handling not included. The Beginner’s Observing Guide Extensively revised and now in its fifth edition, The Beginner’s Observing Guide is for a variety of observers, from the beginner with no experience to the intermediate who would appreciate the clear, helpful guidance here available on an expanded variety of topics: constellations, bright stars, the motions of the heavens, lunar features, the aurora, and the zodiacal light. New sections include: lunar and planetary data through 2010, variable-star observing, telescope information, beginning astrophotography, a non-technical glossary of astronomical terms, and directions for building a properly scaled model of the solar system. Written by astronomy author and educator, Leo Enright; 200 pages, 6 colour star maps, 16 photographs, otabinding. Price: $19.95 plus shipping & handling. Skyways: Astronomy Handbook for Teachers Teaching Astronomy? Skyways Makes it Easy! Written by a Canadian for Canadian teachers and astronomy educators, Skyways is Canadian curriculum-specific; pre-tested by Canadian teachers; hands-on; interactive; geared for upper elementary, middle school, and junior-high grades; fun and easy to use; cost-effective. -

Planetary Science : a Lunar Perspective

APPENDICES APPENDIX I Reference Abbreviations AJS: American Journal of Science Ancient Sun: The Ancient Sun: Fossil Record in the Earth, Moon and Meteorites (Eds. R. 0.Pepin, et al.), Pergamon Press (1980) Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta Suppl. 13 Ap. J.: Astrophysical Journal Apollo 15: The Apollo 1.5 Lunar Samples, Lunar Science Insti- tute, Houston, Texas (1972) Apollo 16 Workshop: Workshop on Apollo 16, LPI Technical Report 81- 01, Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston (1981) Basaltic Volcanism: Basaltic Volcanism on the Terrestrial Planets, Per- gamon Press (1981) Bull. GSA: Bulletin of the Geological Society of America EOS: EOS, Transactions of the American Geophysical Union EPSL: Earth and Planetary Science Letters GCA: Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta GRL: Geophysical Research Letters Impact Cratering: Impact and Explosion Cratering (Eds. D. J. Roddy, et al.), 1301 pp., Pergamon Press (1977) JGR: Journal of Geophysical Research LS 111: Lunar Science III (Lunar Science Institute) see extended abstract of Lunar Science Conferences Appendix I1 LS IV: Lunar Science IV (Lunar Science Institute) LS V: Lunar Science V (Lunar Science Institute) LS VI: Lunar Science VI (Lunar Science Institute) LS VII: Lunar Science VII (Lunar Science Institute) LS VIII: Lunar Science VIII (Lunar Science Institute LPS IX: Lunar and Planetary Science IX (Lunar and Plane- tary Institute LPS X: Lunar and Planetary Science X (Lunar and Plane- tary Institute) LPS XI: Lunar and Planetary Science XI (Lunar and Plane- tary Institute) LPS XII: Lunar and Planetary Science XII (Lunar and Planetary Institute) 444 Appendix I Lunar Highlands Crust: Proceedings of the Conference in the Lunar High- lands Crust, 505 pp., Pergamon Press (1980) Geo- chim. -

July 2020 in This Issue Online Readers, ALPO Conference November 6-7, 2020 2 Lunar Calendar July 2020 3 Click on Images an Invitation to Join ALPO 3 for Hyperlinks

A publication of the Lunar Section of ALPO Edited by David Teske: [email protected] 2162 Enon Road, Louisville, Mississippi, USA Recent back issues: http://moon.scopesandscapes.com/tlo_back.html July 2020 In This Issue Online readers, ALPO Conference November 6-7, 2020 2 Lunar Calendar July 2020 3 click on images An Invitation to Join ALPO 3 for hyperlinks. Observations Received 4 By the Numbers 7 Submission Through the ALPO Image Achieve 4 When Submitting Observations to the ALPO Lunar Section 9 Call For Observations Focus-On 9 Focus-On Announcement 10 2020 ALPO The Walter H. Haas Observer’s Award 11 Sirsalis T, R. Hays, Jr. 12 Long Crack, R. Hill 13 Musings on Theophilus, H. Eskildsen 14 Almost Full, R. Hill 16 Northern Moon, H. Eskildsen 17 Northwest Moon and Horrebow, H. Eskildsen 18 A Bit of Thebit, R. Hill 19 Euclides D in the Landscape of the Mare Cognitum (and Two Kipukas?), A. Anunziato 20 On the South Shore, R. Hill 22 Focus On: The Lunar 100, Features 11-20, J. Hubbell 23 Recent Topographic Studies 43 Lunar Geologic Change Detection Program T. Cook 120 Key to Images in this Issue 134 These are the modern Golden Days of lunar studies in a way, with so many new resources available to lu- nar observers. Recently, we have mentioned Robert Garfinkle’s opus Luna Cognita and the new lunar map by the USGS. This month brings us the updated, 7th edition of the Virtual Moon Atlas. These are all wonderful resources for your lunar studies. -

Facts & Features Lunar Surface Elevations Six Apollo Lunar

Greek Mythology Quadrants Maria & Related Features Lunar Surface Elevations Facts & Features Selene is the Moon and 12 234 the goddess of the Moon, 32 Diameter: 2,160 miles which is 27.3% of Earth’s equatorial diameter of 7,926 miles 260 Lacus daughter of the titans 71 13 113 Mare Frigoris Mare Humboldtianum Volume: 2.03% of Earth’s volume; 49 Moons would fit inside Earth 51 103 Mortis Hyperion and Theia. Her 282 44 II I Sinus Iridum 167 125 321 Lacus Somniorum Near Side Mass: 1.62 x 1023 pounds; 1.23% of Earth’s mass sister Eos is the goddess 329 18 299 Sinus Roris Surface Area: 7.4% of Earth’s surface area of dawn and her brother 173 Mare Imbrium Mare Serenitatis 85 279 133 3 3 3 Helios is the Sun. Selene 291 Palus Mare Crisium Average Density: 3.34 gm/cm (water is 1.00 gm/cm ). Earth’s density is 5.52 gm/cm 55 270 112 is often pictured with a 156 Putredinis Color-coded elevation maps Gravity: 0.165 times the gravity of Earth 224 22 237 III IV cresent Moon on her head. 126 Mare Marginis of the Moon. The difference in 41 Mare Undarum Escape Velocity: 1.5 miles/sec; 5,369 miles/hour Selenology, the modern-day 229 Oceanus elevation from the lowest to 62 162 25 Procellarum Mare Smythii Distances from Earth (measured from the centers of both bodies): Average: 238,856 term used for the study 310 116 223 the highest point is 11 miles. -

THE SHAPE and ELEVATION ANALYSIS of LUNAR CRATER's TRUE MARGIN. Bo Li1, Zongcheng Ling1, Jiang Zhang1, Zhongchen Wu1, Yuheng

46th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2015) 1709.pdf THE SHAPE AND ELEVATION ANALYSIS OF LUNAR CRATER'S TRUE MARGIN. Bo Li1, Zongcheng Ling1, Jiang Zhang1, Zhongchen Wu1, Yuheng Ni1, Jian Chen1.1 Shandong Provincial Key Laboratory of Optical Astronomy and Solar-Terrestrial Environment; Insitute of Space Sciences, Shandong University, Weihai 264209, China, ([email protected]). Introduction: Although rare for Earth and other plane- 1(xk-1, yk-1) starting at an arbitrary point P0 (x0, y0). The tary bodies, impact cratering is a common geologic location of the center of the crater C is calculated from process in planetary evolution history. The Moon is its centroid, pockmarked with literally billions of craters, which 푘−1 푥 푘−1 푦 퐶 = 푖=0 푖, 퐶 = 푖=0 푖 range in size from microscopic pits on the surfaces of 푥 푘 푦 푘 rock specimens to huge, circular impact basins with The shape of a depression’s boundary is de- hundreds or even thounds of kilometers in diameter. scribed by the polar function r θ with the origin lo- Recognition and evaluation of the impact processes cated at C. In order to extract depressions’ shapes can provide an essential interpretive tool for under- based on just a few points we calculate its Fourier ex- standing planets and their geologic evolution [1]. The pansion [3]: 푘−1 푠푖푛 (푛∗휃 ) 푘−1 푐표푠 (푛∗휃 ) 푘 regular and irregular shape and morphology of crater 푎 = 푖=0 푖 ; 푏 = 푖=0 푖 ; 푟 = . in different ages retain key information (e.g., impact 푛 푘 푛 푘 0 휋 direction and velocity) of the impact processes during The fourier coefficients ai, and bi pertain to its shape. -

Graphical Evidence for the Solar Coronal Structure During the Maunder Minimum: Comparative Study of the Total Eclipse Drawings in 1706 and 1715

J. Space Weather Space Clim. 2021, 11,1 Ó H. Hayakawa et al., Published by EDP Sciences 2021 https://doi.org/10.1051/swsc/2020035 Available online at: www.swsc-journal.org Topical Issue - Space climate: The past and future of solar activity RESEARCH ARTICLE OPEN ACCESS Graphical evidence for the solar coronal structure during the Maunder minimum: comparative study of the total eclipse drawings in 1706 and 1715 Hisashi Hayakawa1,2,3,4,*, Mike Lockwood5,*, Matthew J. Owens5, Mitsuru Sôma6, Bruno P. Besser7, and Lidia van Driel – Gesztelyi8,9,10 1 Institute for Space-Earth Environmental Research, Nagoya University, 4648601 Nagoya, Japan 2 Institute for Advanced Researches, Nagoya University, 4648601 Nagoya, Japan 3 Science and Technology Facilities Council, RAL Space, Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, Harwell Campus, OX11 0QX Didcot, UK 4 Nishina Centre, Riken, 3510198 Wako, Japan 5 Department of Meteorology, University of Reading, RG6 6BB Reading, UK 6 National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, 1818588 Mitaka, Japan 7 Space Research Institute, Austrian Academy of Sciences, 8042 Graz, Austria 8 Mullard Space Science Laboratory, University College London, RH5 6NT Dorking, UK 9 LESIA, Observatoire de Paris, Université PSL, CNRS, Sorbonne Université, Université Paris Diderot, Sorbonne Paris Cité, 92195 Meudon, France 10 Konkoly Observatory, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, 1121 Budapest, Hungary Received 18 October 2019 / Accepted 29 June 2020 Abstract – We discuss the significant implications of three eye-witness drawings of the total solar eclipse on 1706 May 12 in comparison with two on 1715 May 3, for our understanding of space climate change. These events took place just after what has been termed the “deep Maunder Minimum” but fall within the “extended Maunder Minimum” being in an interval when the sunspot numbers start to recover. -

Lunar Impact Basins Revealed by Gravity Recovery and Interior

Lunar impact basins revealed by Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory measurements Gregory Neumann, Maria Zuber, Mark Wieczorek, James Head, David Baker, Sean Solomon, David Smith, Frank Lemoine, Erwan Mazarico, Terence Sabaka, et al. To cite this version: Gregory Neumann, Maria Zuber, Mark Wieczorek, James Head, David Baker, et al.. Lunar im- pact basins revealed by Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory measurements. Science Advances , American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), 2015, 1 (9), pp.e1500852. 10.1126/sci- adv.1500852. hal-02458613 HAL Id: hal-02458613 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02458613 Submitted on 26 Jun 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. RESEARCH ARTICLE PLANETARY SCIENCE 2015 © The Authors, some rights reserved; exclusive licensee American Association for the Advancement of Science. Distributed Lunar impact basins revealed by Gravity under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial License 4.0 (CC BY-NC). Recovery and Interior Laboratory measurements 10.1126/sciadv.1500852 Gregory A. Neumann,1* Maria T. Zuber,2 Mark A. Wieczorek,3 James W. Head,4 David M. H. Baker,4 Sean C. Solomon,5,6 David E. Smith,2 Frank G.