31 the Pragmatic Functions of Turning Discourse Markers: “Danshi(但是)”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Literature of China in the Twentieth Century

BONNIE S. MCDOUGALL KA此1 LOUIE The Literature of China in the Twentieth Century 陪詞 Hong Kong University Press 挫芋臨眷戀犬,晶 lll 聶士 --「…- pb HOMAMnEPgUimmm nrRgnIWJM inαJ m1ιLOEbq HHny可 rryb的問可c3 們 unn 品 Fb 心 油 β 7 叫 J『 。 Bonnie McDougall and Kam Louie, 1997 ISBN 962 209 4449 First published in the United Kingdom in 1997 by C. Hurst & Co. (Publishers) Ltd. This soft cover edition published in 1997 by Hong Kong University Press is available in Hong Kong, China and Taiwan All righ臼 reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher. Printed in England CONTENTS Acknowledgements page v Chapters 1. Introduction 1 Part I. 1900-1937 2. Towards a New Culture 13 3. Poetry: The Transformation of the Past 31 4. Fiction: The Narrative Subject 82 5. Drama: Writing Performance 153 Part II. 1938-1965 6. Return to Tradition 189 7. Fiction: Searching for Typicality 208 8. Poetry: The Challenge of Popularisation 261 9. Drama: Performing for Politics 285 Part III. 1966-1989 10. The Reassertion of Modernity 325 11. Drama: Revolution and Reform 345 12. Fiction: Exploring Alternatives 368 13. Poe世y: The Challenge of Modernity 421 14. Conclusion 441 Further Reading 449 Glossary of Titles 463 Index 495 Vll INTRODUCTION Classical Chinese poet可 and the great traditional novels are widely admired by readers throughout the world. Chinese literature in this centu可 has not yet received similar acclaim. -

ABSTRACT Title of Document: the ANTI-CONFUCIAN CAMPAIGN

ABSTRACT Title of Document: THE ANTI-CONFUCIAN CAMPAIGN DURING THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION, AUGUST 1966-JANUARY 1967 Zehao Zhou, Doctor of Philosophy, 2011 Directed By: Professor James Gao, Department of History This dissertation examines the attacks on the Three Kong Sites (Confucius Temple, Confucius Mansion, Confucius Cemetery) in Confucius’s birthplace Qufu, Shandong Province at the start of the Cultural Revolution. During the height of the campaign against the Four Olds in August 1966, Qufu’s local Red Guards attempted to raid the Three Kong Sites but failed. In November 1966, Beijing Red Guards came to Qufu and succeeded in attacking the Three Kong Sites and leveling Confucius’s tomb. In January 1967, Qufu peasants thoroughly plundered the Confucius Cemetery for buried treasures. This case study takes into consideration all related participants and circumstances and explores the complicated events that interwove dictatorship with anarchy, physical violence with ideological abuse, party conspiracy with mass mobilization, cultural destruction with revolutionary indo ctrination, ideological vandalism with acquisitive vandalism, and state violence with popular violence. This study argues that the violence against the Three Kong Sites was not a typical episode of the campaign against the Four Olds with outside Red Guards as the principal actors but a complex process involving multiple players, intraparty strife, Red Guard factionalism, bureaucratic plight, peasant opportunism, social ecology, and ever- evolving state-society relations. This study also maintains that Qufu locals’ initial protection of the Three Kong Sites and resistance to the Red Guards were driven more by their bureaucratic obligations and self-interest rather than by their pride in their cultural heritage. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 142 4th International Conference on Education, Language, Art and Inter-cultural Communication (ICELAIC 2017) A Study on the Translation of "Sister" by Lu Yao under the Perspective of Translation Ethics Xiaohui Zhang Xi’an Fanyi University Xi’an, China Abstract—Under the new situation, the put forth of “the Belt Kejing's novella "the blue flower on handcuffs" won the fifth and Road” and the implementation of "going out" strategy, give Lu Xun Literature Award. There was a new round of creative Shaanxi literature a vigorous vitality. In 2011, the writing of writings wave in Shaanxi, which greatly enhances the brand overseas literature promotion program compiled the English influence of Shaanxi literary writers. At the same time, the version "short film collection of Shaanxi writers". In the process writers implemented Shaanxi literature overseas translation of promoting these literary works, both the translation referral plan (shorted for SLOT plan) and compiled and organization of the authorities, translators, the translation published a large-scale commemorative collection of sino- strategy and the publishers have an impact on the English russian "love of Russia", the English version of "Short story version, the quality of the translation and the publishing scope collection of Shaanxi writers". This is the first collectively while All of the these factors belong to the category of translation translated works of provincial Writers in China. In addition, ethics research. Therefore, the author, guided by the theory of translation ethics, analyzes the current situation of Shaanxi Ye Guangqin's English version "Qing mu chuan" has been literary works and guides the practice of translation. -

Veda Publishing House of the Slovak Academy of Sciences Slovak Academy of Sciences

VEDA PUBLISHING HOUSE OF THE SLOVAK ACADEMY OF SCIENCES SLOVAK ACADEMY OF SCIENCES INSTITUTE OF LITERARY SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF ORIENTAL STUDIES EDITORS JOZEF GENZOR VIKTOR KRUPA ASIAN AND AFRICAN STUDIES SLOVAK ACADEMY OF SCIENCES BRATISLAVA INSTITUTE OF LITERARY SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF ORIENTAL STUDIES XXIII 1987 1988 VEDA, PUBLISHING HOUSE OF THE SLOVAK ACADEMY OF SCIENCES • BRATISLAVA CURZON PRESS • LONDON PUBLISHED OUTSIDE THE SOCIALIST COUNTRIES SOLELY BY CURZON PRESS LTD • LONDON ISBN 0 7007 0211 3 ISBN 0571 2 7 4 2 © VEDA, VYDAVATEĽSTVO SLOVENSKEJ AKADÉMIE VIED, 1988 CONTENTS A rtic le s G á I i k, Marián: Some Remarks on the Process of Emancipation in Modern Asian and African Literatures ................................................................................................................... 9 G ru ner, Fritz: Some Remarks on Developmental Tendencies in Chinese Contempo rary Literature since 1979 ....................................................................................................... 31 Doležalová, Anna: New Qualities in Contemporary Chinese Stories (1979 — Early 1 9 8 0 s ).................................................................................................................................. 45 Kalvodová, Dana: Time and Space Relations in Kong Shangren's Drama The Peach Blossom Fan ........................................................................................................................... 69 Kuťka, Karol: Some Reflections on the Atomic Bomb Literature and Literature on the Atomic -

Cultural Revolution

Chinese Fiction of the Cultural Revolution Lan Yang -w~*-~:tItB.~±. HONG KONG UNIVERSITY PRESS Hong Kong University Press 14/F Hing Wai Centre 7 Tin Wan Praya Road Aberdeen, Hong Kong © Hong Kong University Press 1998 ISBN 962 209 467 8 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in Hong Kong by Caritas Printing Training Centre. Contents List of Tables ix Foreword xi Preface xiii Introduction 1 • CR novels and CR agricultural novels 3 • Literary Policy and Theory in the Cultural Revolution 14 Part I Characterization of the Main Heroes 33 Introduction to Part I 35 1. Personal Background 39 2. Physical Qualities 49 • Strong Constitution and Vigorous Air 50 • Unsophisticated Features and Expression 51 • Dignified Manner and Awe~ Inspiring Bearing 52 • Big and Bright Piercing Eyes 53 • A Sonorous and Forceful Voice 53 vi • Contents 3. Ideological Qualities 61 • Consciousness of Class, Road and Line Struggles 61 • Consciousness of Altruism and Collectivism 66 4. Temperamental and Behavioural Qualities 75 • Categories of Temperamental and Behavioural Qualities 75 • Social and Cultural Foundations of Temperamental and Behavioural Qualities 88 5. Prominence Given to the Main Heroes 97 • Practice of the 'Three Prominences' 97 • Other Stock Points Concerning Prominence of the Main Heroes 118 Part II Lexical Style 121 Introduction to Part II 123 • Selection of the Sample 124 • Units and Levels of Analysis 125 • Categories of Stylistic Items versus References 127 • Exhaustive or Sample Measurement 128 • The Statistical Process 128 6. -

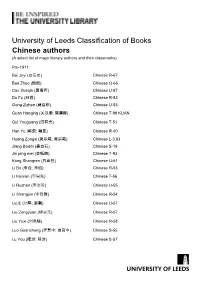

University of Leeds Classification of Books Chinese Authors (A Select List of Major Literary Authors and Their Classmarks)

University of Leeds Classification of Books Chinese authors (A select list of major literary authors and their classmarks) Pre-1911: Bai Juyi (白居易) Chinese R-67 Bao Zhao (鮑照) Chinese Q-66 Cao Xueqin (曹雪芹) Chinese U-87 Du Fu (杜甫) Chinese R-83 Gong Zizhen (龔自珍) Chinese U-53 Guan Hanqing (关汉卿; 關漢卿) Chinese T-99 KUAN Gui Youguang (归有光) Chinese T-51 Han Yu (韩愈; 韓愈) Chinese R-40 Huang Zongxi (黄宗羲; 黃宗羲) Chinese L-3.83 Jiang Baishi (姜白石) Chinese S-19 Jin ping mei (金瓶梅) Chinese T-93 Kong Shangren (孔尚任) Chinese U-51 Li Bo (李白; 李伯) Chinese R-53 Li Kaixian (李開先) Chinese T-56 Li Ruzhen (李汝珍) Chinese U-55 Li Shangyin (李商隱) Chinese R-54 Liu E (刘鹗; 劉鶚) Chinese U-57 Liu Zongyuan (柳宗元) Chinese R-57 Liu Yuxi (刘禹锡) Chinese R-58 Luo Guanzhong (罗贯中; 羅貫中) Chinese S-55 Lu You (陆游; 陸游) Chinese S-57 Ma Zhiyuan (马致远; 馬致遠) Chinese T-59 Meng Haoran (孟浩然) Chinese R-60 Ouyang Xiu (欧阳修; 歐陽修) Chinese S-64 Pu Songling (蒲松龄; 蒲松齡) Chinese U-70 Qu Yuan (屈原) Chinese Q-20 Ruan Ji (阮籍) Chinese Q-50 Shui hu zhuan (水浒传; 水滸傳) Chinese T-75 Su Manshu (苏曼殊; 蘇曼殊) Chinese U-99 SU Su Shi (苏轼; 蘇軾) Chinese S-78 Tang Xianzu (汤显祖; 湯顯祖) Chinese T-80 Tao Qian (陶潛) Chinese Q-81 Wang Anshi (王安石) Chinese S-89 Wang Shifu (王實甫) Chinese S-90 Wang Shizhen (王世貞) Chinese T-92 Wu Cheng’en (吳承恩) Chinese T-99 WU Wu Jingzi (吴敬梓; 吳敬梓) Chinese U-91 Wang Wei (王维; 王維) Chinese R-90 Ye Shi (叶适; 葉適) Chinese S-96 Yu Xin (庾信) Chinese Q-97 Yuan Mei (袁枚) Chinese U-96 Yuan Zhen (元稹) Chinese R-96 Zhang Juzheng (張居正) Chinese T-19 After 1911: [The catalogue should be used to verify classmarks in view of the on-going -

Han Yu Pin Yin / English Title Chinese Title Other Titles in NTU Library

Other titles in NTU Library (highlighted titles are displayed along with the autographed titles) Exhibited Title Author Call no. (NTU) Location Han Yu Pin Yin / English title Chinese Title 阿城 Acheng, 1949- Chang chi yu tong shi 常識與通識 PL2833.A3C456 HSS Library Pian di feng liu 遍地風流 PL2833.A3P581 HSS Library Shuang 爽 PL2877.S53S562 HSS Library Weinisi ri ji 威尼斯日記 PL2833.A3W415 HSS Library Xian hua xian shuo 閑話閑說 PL2833.A3X6 HSS Library Xiao cheng zhi chun 小城之春 PL2833.A3X6C HSS Library Zhen guang zhi zi 贞观之治 PL2833.A3Z63G HSS Library 艾青 Ai, Qing, 1910- Ai Qing ming zuo xin shang 艾青名作欣赏 PL2833.I2A288 HSS Library Ai Qing san wen 艾青散文 (2 vols) PL2833.I2D682 HSS Library Ai Qing tan shi 艾青谈诗 PL2333.A288 HSS library/Closed stack Ai Qing 艾青 PL2833.I2A288 HSS Library Bei fang 北方 PL2833.I2B422 HSS Library Cai se de shi 彩色的詩 PL2833.I2A288C HSS Library Chun tian 春天 PL2833.I2C559 HSS Library Dayanhe: wo de bao mu 大堰河 : 我的保姆 PL2833.I2D275 HSS Library Huan hu ji 歡呼集 PL2833.I2H874 HSS Library Lo ye ji 落叶集 PL2833.I2L964 HSS Library Shi lun 诗论 PL2307.A288Z HSS Library/closed stack 艾蕪 Ai, Wu. Ai Fu duan pian xiao shuo ji 艾芜短篇小说集 PL2736.I27A288D HSS Library Ai Fu duan pian xiao shuo xuan 艾芜短篇小说选 PL2736.I27A288W HSS Library Ai Fu xiao shuo xuan 艾芜小说选 PL2736.I27A288 HSS Library Ai Fu zhong pian xiao shuo ji 艾芜中篇小说集. PL2736.I27A288X HSS Library Ai Fu zhuan 艾芜传 PL2736.I27W246A HSS Library Liang ge shuo sheng po 兩個收生婆 PL3095.L693 HSS Library Sha ding Ai Fu de xiao shuo shi jie 沙汀艾芜的小说世界 PL2922.T8W246 HSS Library Wang shi sui xiang 往事随想 PL2736.I27W246 HSS Library -

A Prestigious Translator and Writer of Children’S Literature

A Study of Chinese Translations and Interpretations of H.C. Andersen's Tales History and Influence Li, Wenjie Publication date: 2014 Document version Early version, also known as pre-print Citation for published version (APA): Li, W. (2014). A Study of Chinese Translations and Interpretations of H.C. Andersen's Tales: History and Influence. Det Humanistiske Fakultet, Københavns Universitet. Download date: 01. okt.. 2021 FACULTY OF HUMANITIES UNIVERSITY OF COPENHAGEN PhD thesis Li Wenjie Thesis title A STUDY OF CHINESE TRANSLATIONS AND INTERPRETATIONS OF H.C. ANDERSEN’S TALES: HISTORY AND INFLUENCE Academic advisor: Henrik Gottlieb Submitted: 23/01/2014 Institutnavn: Institut for Engelsk, Germansk and Romansk Name of department: Department of English, Germanic and Romance Studies Author: Li Wenjie Titel og evt. undertitel: En undersøgelse af kinesisk oversættelse og fortolkninger af H. C. Andersens eventyr: historie og indflydelse Title / Subtitle: A Study of Chinese Translations and Interpretations of H.C. Andersen’s Tales: History and Influence Subject description: H. C. Andersen, Tales, Translation History, Interpretation, Chinese Translation Academic advisor: Henrik Gottlieb Submitted: 23. Jan. 2014 Declaration I hereby declare that this thesis is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge, it contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due acknowledgement has been made in the text. It has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification except as specified. Contents -

Hervé Renard Catalogue Spécial Asie

Hervé Renard Catalogue Spécial Asie Février 2018 Rue du Kriekenput, 83 1180 Bruxelles Tél. +32-2-375.47.49 e-mail: [email protected] uniquement par correspondance Bhoutan 1. FÖLLMI O., Bhoutan - Le temps d’un royaume, Paris, Editions de la Martinière, 1998, 25x32, rel.éd. avec jaquette, illustr. coul., 1041g., 15€ Birmanie 2. Burmese Monk’s Tales - Collected, translated and introduced by Maung Htin Aung, New York, Columbia University Press, 1966, 16x23, 181p., rel.éd. avec jaquette, 477g., 10€ 3. CUSHING J.N., Elementary Handbook of the Shan Language, Rangoon, American Baptist Mission Press, 1888, 14x20, 272p., rel.éd. sans jaquette, 410g., 10€ 4. VOSSION L., Grammaire Franco-Birmane, Paris, Editeur Ernest Leroux, 1891, 12x18, 111p., rel.éd. sans jaquette, 282g., 20€ 5. WADE J./BINNEY J.P., Anglo-Karen Dictionary (revised and abridged by Blackwell G.E.), Rangoon, Baptist Board of Publications, 1954, 13x19, 543p., rel.éd. sans jaquette, 334g., 10€ Cambodge 6. AUBOYER J., L’art khmer au musée Guimet (Paris), Paris, Editions Manesse, 1965, 25x33, 43p., en feuilles, illustr. n-b par L. Von Matt, 808g., 10€ 7. Chant de Paix - Poème au peuple Khmèr pour saluer l’édition cambodgienne du Vinaya Pitaka, la première corbeille du canon bouddhique, Institut Bouddhique, 25x16, br., 120g., 10€ 8. GITEAU M./GUERET D., L’art khmer - Reflet des civilisations d’Angkor, Paris, ASA Editions/Somogy Editions d’art, 1997, 27x31, 157p., rel.éd. avec jaquette, illustr. coul. par T. Renaut, 1450g. 15€ 9. GNOK T., La rose de Païlin, Paris, L’Harmattan, 1995, 13,5x21,5, 77p., br., 121gr., 10€ 10. -

The Literary Field of Twentieth-Century China Chinese Worlds

The Literary Field of Twentieth-Century China Chinese Worlds Chinese Worlds publishes high-quality scholarship, research monographs, and source collections on Chinese history and society from 1900 into the next century. "Worlds" signals the ethnic, cultural, and political multiformity and regional diversity of China, the cycles of unity and division through which China's modern history has passed, and recent research trends toward regional studies and local issues. It also signals that Chineseness is not contained within territorial borders - overseas Chinese communities in all countries and regions are also "Chinese worlds". The editors see them as part of a political, economic, social, and cultural continuum that spans the Chinese mainland, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macau, South-East Asia, and the world. The focus of Chinese Worlds is on modern politics and society and history. It includes both history in its broader sweep and specialist monographs on Chinese politics, anthropology, political economy, sociology, education, and the social-science aspects of culture and religions. The Literary Field of New Fourth Army Twentieth-Century China Communist Resistance along the Edited by Michel Hockx Yangtze and the Huai, 1938-1941 Gregor Benton Chinese Business in Malaysia Accumulation, Ascendance, A Road is Made Accommodation Communism in Shanghai 1920-1927 Edmund Terence Gomez Steve Smith Internal and International Migration The Bolsheviks and the Chinese Chinese Perspectives Revolution 1919-1927 Edited by Frank N. Pieke and Hein Mallee Alexander -

Liu, Anmeng Final Phd Thesis.Pdf (2.793Mb)

An ordinary China: Reading ‘small-town youth’ for difference in a northwestern county town A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Human Geography at the University of Canterbury By Anmeng Liu October 2020 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Writing this acknowledgement in complete solitude under a two-week quarantine in a Shanghai hotel room, I cannot help but be overwhelmed with thoughts and emotions. Montages of faces, voices and moments constantly form in my head – it is impossible to name all of those who were with me over the course of this challenging yet rewarding thesis journey. First and foremost, my sincere gratitude goes to Dr Kelly Dombroski for being the cornerstone of this PhD project. She was not only a source of academic guidance, but also a caring and inspiring mentor who has seen me through many difficult times both academically and personally. Kelly, thank you for taking me on, cultivating my potential and nurturing me with opportunities of all kinds along the way. I would also like to thank my co-supervisors Dr Zhifang Song and Dr Chris Chen for their priceless feedback and encouragement. My gratitude also goes to all the staff and postgraduates in the previous Department of Geography and the newly merged School of Earth and Environment — Thank you Prof Peyman Zawar-Reza, Prof David Conradson, Dr Kerryn Hawke, Adam Prana, Ambika Malik, Dr Alison Watkins, Benjamin Boosch, Caihuan Duojie, Dr Huong Do, Dr Helen Fitt, David Garcia, Dr Daisuke Seto, Julia Torres, Levi Mutambo, Rasool Porhemmat, Sonam Pem, Rajasweta Datta, Ririn Agnes Haryani, S M Waliuzzaman, Trias Rahardianto, Tingting Zhang, Zhuoga Qimei. -

The Analysis of Narrative Expression Forms in Contemporary Chinese Novels Yi-Duo BIAN

2021 International Conference on Education, Humanity and Language, Art (EHLA 2021) ISBN: 978-1-60595-137-9 The Analysis of Narrative Expression Forms in Contemporary Chinese Novels Yi-duo BIAN1,a,* 1College of Foreign Languages, Zhaotong University, Zhaotong, Yunnan, China [email protected] *corresponding author Keywords: Novel, Narrative framework, Embedded narrative, Experiential. Abstract. As an important part of literary form, novels have a wide audience. Novels play an important role in recording and reflecting the changes of history, society and people's spiritual consciousness. The novel has various forms of expression, and its narrative methods and techniques have been fully developed. Through the interpretation of the narrative expression of the novel, we can find that: with the development of the times, the change of social background, the change of people's spiritual ideology, the expression forms and methods of the novel also show diversity. Mining and refining the epitome of historical development from novels also reflects its importance as a literary carrier. 1. Introduction From the process of the history of human civilization, history needs to be recorded, analyzed and inherited. History and culture are the roots of a nation. Any nation has its own specific development history, which is closely related to its development background. There are many ways to record history, such as general history, chronological history, thematic history, character history, memoir, painting, physical preservation, image recording, etc. As a carrier, literary works have played an important role and occupied an important position in thousands of years of historical development. Literary works are not only recorders of history, but also living fossils of studying history.