Imperial-Time-Order Ideas, History, and Modern China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Literature of China in the Twentieth Century

BONNIE S. MCDOUGALL KA此1 LOUIE The Literature of China in the Twentieth Century 陪詞 Hong Kong University Press 挫芋臨眷戀犬,晶 lll 聶士 --「…- pb HOMAMnEPgUimmm nrRgnIWJM inαJ m1ιLOEbq HHny可 rryb的問可c3 們 unn 品 Fb 心 油 β 7 叫 J『 。 Bonnie McDougall and Kam Louie, 1997 ISBN 962 209 4449 First published in the United Kingdom in 1997 by C. Hurst & Co. (Publishers) Ltd. This soft cover edition published in 1997 by Hong Kong University Press is available in Hong Kong, China and Taiwan All righ臼 reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher. Printed in England CONTENTS Acknowledgements page v Chapters 1. Introduction 1 Part I. 1900-1937 2. Towards a New Culture 13 3. Poetry: The Transformation of the Past 31 4. Fiction: The Narrative Subject 82 5. Drama: Writing Performance 153 Part II. 1938-1965 6. Return to Tradition 189 7. Fiction: Searching for Typicality 208 8. Poetry: The Challenge of Popularisation 261 9. Drama: Performing for Politics 285 Part III. 1966-1989 10. The Reassertion of Modernity 325 11. Drama: Revolution and Reform 345 12. Fiction: Exploring Alternatives 368 13. Poe世y: The Challenge of Modernity 421 14. Conclusion 441 Further Reading 449 Glossary of Titles 463 Index 495 Vll INTRODUCTION Classical Chinese poet可 and the great traditional novels are widely admired by readers throughout the world. Chinese literature in this centu可 has not yet received similar acclaim. -

ABSTRACT Title of Document: the ANTI-CONFUCIAN CAMPAIGN

ABSTRACT Title of Document: THE ANTI-CONFUCIAN CAMPAIGN DURING THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION, AUGUST 1966-JANUARY 1967 Zehao Zhou, Doctor of Philosophy, 2011 Directed By: Professor James Gao, Department of History This dissertation examines the attacks on the Three Kong Sites (Confucius Temple, Confucius Mansion, Confucius Cemetery) in Confucius’s birthplace Qufu, Shandong Province at the start of the Cultural Revolution. During the height of the campaign against the Four Olds in August 1966, Qufu’s local Red Guards attempted to raid the Three Kong Sites but failed. In November 1966, Beijing Red Guards came to Qufu and succeeded in attacking the Three Kong Sites and leveling Confucius’s tomb. In January 1967, Qufu peasants thoroughly plundered the Confucius Cemetery for buried treasures. This case study takes into consideration all related participants and circumstances and explores the complicated events that interwove dictatorship with anarchy, physical violence with ideological abuse, party conspiracy with mass mobilization, cultural destruction with revolutionary indo ctrination, ideological vandalism with acquisitive vandalism, and state violence with popular violence. This study argues that the violence against the Three Kong Sites was not a typical episode of the campaign against the Four Olds with outside Red Guards as the principal actors but a complex process involving multiple players, intraparty strife, Red Guard factionalism, bureaucratic plight, peasant opportunism, social ecology, and ever- evolving state-society relations. This study also maintains that Qufu locals’ initial protection of the Three Kong Sites and resistance to the Red Guards were driven more by their bureaucratic obligations and self-interest rather than by their pride in their cultural heritage. -

Veda Publishing House of the Slovak Academy of Sciences Slovak Academy of Sciences

VEDA PUBLISHING HOUSE OF THE SLOVAK ACADEMY OF SCIENCES SLOVAK ACADEMY OF SCIENCES INSTITUTE OF LITERARY SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF ORIENTAL STUDIES EDITORS JOZEF GENZOR VIKTOR KRUPA ASIAN AND AFRICAN STUDIES SLOVAK ACADEMY OF SCIENCES BRATISLAVA INSTITUTE OF LITERARY SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF ORIENTAL STUDIES XXIII 1987 1988 VEDA, PUBLISHING HOUSE OF THE SLOVAK ACADEMY OF SCIENCES • BRATISLAVA CURZON PRESS • LONDON PUBLISHED OUTSIDE THE SOCIALIST COUNTRIES SOLELY BY CURZON PRESS LTD • LONDON ISBN 0 7007 0211 3 ISBN 0571 2 7 4 2 © VEDA, VYDAVATEĽSTVO SLOVENSKEJ AKADÉMIE VIED, 1988 CONTENTS A rtic le s G á I i k, Marián: Some Remarks on the Process of Emancipation in Modern Asian and African Literatures ................................................................................................................... 9 G ru ner, Fritz: Some Remarks on Developmental Tendencies in Chinese Contempo rary Literature since 1979 ....................................................................................................... 31 Doležalová, Anna: New Qualities in Contemporary Chinese Stories (1979 — Early 1 9 8 0 s ).................................................................................................................................. 45 Kalvodová, Dana: Time and Space Relations in Kong Shangren's Drama The Peach Blossom Fan ........................................................................................................................... 69 Kuťka, Karol: Some Reflections on the Atomic Bomb Literature and Literature on the Atomic -

Cultural Revolution

Chinese Fiction of the Cultural Revolution Lan Yang -w~*-~:tItB.~±. HONG KONG UNIVERSITY PRESS Hong Kong University Press 14/F Hing Wai Centre 7 Tin Wan Praya Road Aberdeen, Hong Kong © Hong Kong University Press 1998 ISBN 962 209 467 8 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in Hong Kong by Caritas Printing Training Centre. Contents List of Tables ix Foreword xi Preface xiii Introduction 1 • CR novels and CR agricultural novels 3 • Literary Policy and Theory in the Cultural Revolution 14 Part I Characterization of the Main Heroes 33 Introduction to Part I 35 1. Personal Background 39 2. Physical Qualities 49 • Strong Constitution and Vigorous Air 50 • Unsophisticated Features and Expression 51 • Dignified Manner and Awe~ Inspiring Bearing 52 • Big and Bright Piercing Eyes 53 • A Sonorous and Forceful Voice 53 vi • Contents 3. Ideological Qualities 61 • Consciousness of Class, Road and Line Struggles 61 • Consciousness of Altruism and Collectivism 66 4. Temperamental and Behavioural Qualities 75 • Categories of Temperamental and Behavioural Qualities 75 • Social and Cultural Foundations of Temperamental and Behavioural Qualities 88 5. Prominence Given to the Main Heroes 97 • Practice of the 'Three Prominences' 97 • Other Stock Points Concerning Prominence of the Main Heroes 118 Part II Lexical Style 121 Introduction to Part II 123 • Selection of the Sample 124 • Units and Levels of Analysis 125 • Categories of Stylistic Items versus References 127 • Exhaustive or Sample Measurement 128 • The Statistical Process 128 6. -

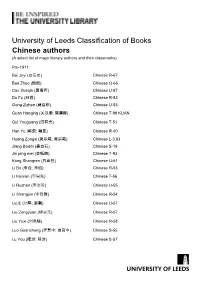

University of Leeds Classification of Books Chinese Authors (A Select List of Major Literary Authors and Their Classmarks)

University of Leeds Classification of Books Chinese authors (A select list of major literary authors and their classmarks) Pre-1911: Bai Juyi (白居易) Chinese R-67 Bao Zhao (鮑照) Chinese Q-66 Cao Xueqin (曹雪芹) Chinese U-87 Du Fu (杜甫) Chinese R-83 Gong Zizhen (龔自珍) Chinese U-53 Guan Hanqing (关汉卿; 關漢卿) Chinese T-99 KUAN Gui Youguang (归有光) Chinese T-51 Han Yu (韩愈; 韓愈) Chinese R-40 Huang Zongxi (黄宗羲; 黃宗羲) Chinese L-3.83 Jiang Baishi (姜白石) Chinese S-19 Jin ping mei (金瓶梅) Chinese T-93 Kong Shangren (孔尚任) Chinese U-51 Li Bo (李白; 李伯) Chinese R-53 Li Kaixian (李開先) Chinese T-56 Li Ruzhen (李汝珍) Chinese U-55 Li Shangyin (李商隱) Chinese R-54 Liu E (刘鹗; 劉鶚) Chinese U-57 Liu Zongyuan (柳宗元) Chinese R-57 Liu Yuxi (刘禹锡) Chinese R-58 Luo Guanzhong (罗贯中; 羅貫中) Chinese S-55 Lu You (陆游; 陸游) Chinese S-57 Ma Zhiyuan (马致远; 馬致遠) Chinese T-59 Meng Haoran (孟浩然) Chinese R-60 Ouyang Xiu (欧阳修; 歐陽修) Chinese S-64 Pu Songling (蒲松龄; 蒲松齡) Chinese U-70 Qu Yuan (屈原) Chinese Q-20 Ruan Ji (阮籍) Chinese Q-50 Shui hu zhuan (水浒传; 水滸傳) Chinese T-75 Su Manshu (苏曼殊; 蘇曼殊) Chinese U-99 SU Su Shi (苏轼; 蘇軾) Chinese S-78 Tang Xianzu (汤显祖; 湯顯祖) Chinese T-80 Tao Qian (陶潛) Chinese Q-81 Wang Anshi (王安石) Chinese S-89 Wang Shifu (王實甫) Chinese S-90 Wang Shizhen (王世貞) Chinese T-92 Wu Cheng’en (吳承恩) Chinese T-99 WU Wu Jingzi (吴敬梓; 吳敬梓) Chinese U-91 Wang Wei (王维; 王維) Chinese R-90 Ye Shi (叶适; 葉適) Chinese S-96 Yu Xin (庾信) Chinese Q-97 Yuan Mei (袁枚) Chinese U-96 Yuan Zhen (元稹) Chinese R-96 Zhang Juzheng (張居正) Chinese T-19 After 1911: [The catalogue should be used to verify classmarks in view of the on-going -

Han Yu Pin Yin / English Title Chinese Title Other Titles in NTU Library

Other titles in NTU Library (highlighted titles are displayed along with the autographed titles) Exhibited Title Author Call no. (NTU) Location Han Yu Pin Yin / English title Chinese Title 阿城 Acheng, 1949- Chang chi yu tong shi 常識與通識 PL2833.A3C456 HSS Library Pian di feng liu 遍地風流 PL2833.A3P581 HSS Library Shuang 爽 PL2877.S53S562 HSS Library Weinisi ri ji 威尼斯日記 PL2833.A3W415 HSS Library Xian hua xian shuo 閑話閑說 PL2833.A3X6 HSS Library Xiao cheng zhi chun 小城之春 PL2833.A3X6C HSS Library Zhen guang zhi zi 贞观之治 PL2833.A3Z63G HSS Library 艾青 Ai, Qing, 1910- Ai Qing ming zuo xin shang 艾青名作欣赏 PL2833.I2A288 HSS Library Ai Qing san wen 艾青散文 (2 vols) PL2833.I2D682 HSS Library Ai Qing tan shi 艾青谈诗 PL2333.A288 HSS library/Closed stack Ai Qing 艾青 PL2833.I2A288 HSS Library Bei fang 北方 PL2833.I2B422 HSS Library Cai se de shi 彩色的詩 PL2833.I2A288C HSS Library Chun tian 春天 PL2833.I2C559 HSS Library Dayanhe: wo de bao mu 大堰河 : 我的保姆 PL2833.I2D275 HSS Library Huan hu ji 歡呼集 PL2833.I2H874 HSS Library Lo ye ji 落叶集 PL2833.I2L964 HSS Library Shi lun 诗论 PL2307.A288Z HSS Library/closed stack 艾蕪 Ai, Wu. Ai Fu duan pian xiao shuo ji 艾芜短篇小说集 PL2736.I27A288D HSS Library Ai Fu duan pian xiao shuo xuan 艾芜短篇小说选 PL2736.I27A288W HSS Library Ai Fu xiao shuo xuan 艾芜小说选 PL2736.I27A288 HSS Library Ai Fu zhong pian xiao shuo ji 艾芜中篇小说集. PL2736.I27A288X HSS Library Ai Fu zhuan 艾芜传 PL2736.I27W246A HSS Library Liang ge shuo sheng po 兩個收生婆 PL3095.L693 HSS Library Sha ding Ai Fu de xiao shuo shi jie 沙汀艾芜的小说世界 PL2922.T8W246 HSS Library Wang shi sui xiang 往事随想 PL2736.I27W246 HSS Library -

A Prestigious Translator and Writer of Children’S Literature

A Study of Chinese Translations and Interpretations of H.C. Andersen's Tales History and Influence Li, Wenjie Publication date: 2014 Document version Early version, also known as pre-print Citation for published version (APA): Li, W. (2014). A Study of Chinese Translations and Interpretations of H.C. Andersen's Tales: History and Influence. Det Humanistiske Fakultet, Københavns Universitet. Download date: 01. okt.. 2021 FACULTY OF HUMANITIES UNIVERSITY OF COPENHAGEN PhD thesis Li Wenjie Thesis title A STUDY OF CHINESE TRANSLATIONS AND INTERPRETATIONS OF H.C. ANDERSEN’S TALES: HISTORY AND INFLUENCE Academic advisor: Henrik Gottlieb Submitted: 23/01/2014 Institutnavn: Institut for Engelsk, Germansk and Romansk Name of department: Department of English, Germanic and Romance Studies Author: Li Wenjie Titel og evt. undertitel: En undersøgelse af kinesisk oversættelse og fortolkninger af H. C. Andersens eventyr: historie og indflydelse Title / Subtitle: A Study of Chinese Translations and Interpretations of H.C. Andersen’s Tales: History and Influence Subject description: H. C. Andersen, Tales, Translation History, Interpretation, Chinese Translation Academic advisor: Henrik Gottlieb Submitted: 23. Jan. 2014 Declaration I hereby declare that this thesis is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge, it contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due acknowledgement has been made in the text. It has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification except as specified. Contents -

Hervé Renard Catalogue Spécial Asie

Hervé Renard Catalogue Spécial Asie Février 2018 Rue du Kriekenput, 83 1180 Bruxelles Tél. +32-2-375.47.49 e-mail: [email protected] uniquement par correspondance Bhoutan 1. FÖLLMI O., Bhoutan - Le temps d’un royaume, Paris, Editions de la Martinière, 1998, 25x32, rel.éd. avec jaquette, illustr. coul., 1041g., 15€ Birmanie 2. Burmese Monk’s Tales - Collected, translated and introduced by Maung Htin Aung, New York, Columbia University Press, 1966, 16x23, 181p., rel.éd. avec jaquette, 477g., 10€ 3. CUSHING J.N., Elementary Handbook of the Shan Language, Rangoon, American Baptist Mission Press, 1888, 14x20, 272p., rel.éd. sans jaquette, 410g., 10€ 4. VOSSION L., Grammaire Franco-Birmane, Paris, Editeur Ernest Leroux, 1891, 12x18, 111p., rel.éd. sans jaquette, 282g., 20€ 5. WADE J./BINNEY J.P., Anglo-Karen Dictionary (revised and abridged by Blackwell G.E.), Rangoon, Baptist Board of Publications, 1954, 13x19, 543p., rel.éd. sans jaquette, 334g., 10€ Cambodge 6. AUBOYER J., L’art khmer au musée Guimet (Paris), Paris, Editions Manesse, 1965, 25x33, 43p., en feuilles, illustr. n-b par L. Von Matt, 808g., 10€ 7. Chant de Paix - Poème au peuple Khmèr pour saluer l’édition cambodgienne du Vinaya Pitaka, la première corbeille du canon bouddhique, Institut Bouddhique, 25x16, br., 120g., 10€ 8. GITEAU M./GUERET D., L’art khmer - Reflet des civilisations d’Angkor, Paris, ASA Editions/Somogy Editions d’art, 1997, 27x31, 157p., rel.éd. avec jaquette, illustr. coul. par T. Renaut, 1450g. 15€ 9. GNOK T., La rose de Païlin, Paris, L’Harmattan, 1995, 13,5x21,5, 77p., br., 121gr., 10€ 10. -

Reading Hong Kong Literature from the Periphery of Modern Chinese Literature : Liu Yichang Studies As an Example = 從現代中 國文學的邊缘看香港文學研究 : 以劉以鬯研究為例

Journal of Modern Literature in Chinese 現代中文文學學報 Volume 10 Issue 1 Vol. 10.1 十卷一期 (Summer 2010) Article 10 7-1-2010 Reading Hong Kong literature from the periphery of modern Chinese literature : Liu Yichang studies as an example = 從現代中 國文學的邊缘看香港文學研究 : 以劉以鬯研究為例 Yuk Kwan, Amanda HSU Lingnan University, Hong Kong Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.ln.edu.hk/jmlc Recommended Citation Hsu, A. Y.-k. (2010). Reading Hong Kong literature from the periphery of modern Chinese literature: Liu Yichang studies as an example = 從現代中國文學的邊缘看香港文學研究 : 以劉以鬯研究為例. Journal of Modern Literature in Chinese, 10(1), 177-186. This JMLC Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Centre for Humanities Research 人文學科研究 中心 at Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Modern Literature in Chinese 現代中文文學學報 by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. process. His practice is a demonstration against this commercialized colonial city by conjuring up the unwanted excesses of a past that does not go away. For Liu, the lived experiences in everyday life can serve as a space of differences or a different mode of temporality that may not be entirely dominated by the totalization and rationalization of capitalism. His reaction to this problem is to turn to fiction. However, this represents a typical response to the problem, for it turns away from the conditions of active existence in favor of a world of contemplative reflection. It is also a kind of critique that emphasizes its critical role and intellectual engagement with consciousness. In other words, it is a form of resistance. -

Remapping the Past Leiden Series in Comparative Historiography

Remapping the Past Leiden Series in Comparative Historiography Editors Axel Schneider Susanne Weigelin-Schwiedrzik VOLUME 3 Remapping the Past Fictions of History in Deng’s China, 1979–1997 By Howard Y.F. Choy LEIDEN • BOSTON 2008 Sections of Chapter 2 have appeared in previous publications under the following titles and special thanks are due to the editors and anonymous reviewers: “‘To Construct an Unknown China’: Ethnoreligious Historiography in Zhang Chengzhi’s Islamic Fiction,” Positions: East Asia Culture Critique 14.3: 687–715. Copyright 2006. All rights reserved. Used by permission of the publisher, Duke University Press. “Historiographic Alternatives for China: Tibet in Contemporary Fiction by Tashi Dawa, Alai, and Ge Fei,” American Journal of Chinese Studies 12.1 (2005): 65–84. “In Quest(ion) of an ‘I’: Identity and Idiocy in Alai’s Red Poppies,” forthcoming Spring 2008 in Modern Tibetan Literature and Social Change, ed. Lauran Hartley and Patricia Schiaffini-Verdani (Duke University Press). This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Choy, Howard Y. F. (Howard Yuen Fung) Remapping the past : fictions of history in Deng’s China, 1979–1997 / By Howard Y.F. Choy. p. cm. – (Leiden series in comparative historiography) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-16704-9 (hbk. : alk. paper) 1. Chinese fiction–20th century–History and criticism. I. Title. II. Title: Fictions of history in Deng’s China, 1979–1997. PL2443.C4455 2008 895.1’090052–dc22 2008011344 ISSN 1574-4493 ISBN 978 90 04 16704 9 Copyright 2008 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. -

Personenregister

PERSONENREGISTER A Cheng = Zhang Acheng 阿城 C 694.215 A Cheng = Wang Acheng 阿成 C 694.254 A Lai 阿來 C 694.341 A Sheng 阿盛 C 698.301 A Ying = Qian Xingcun 阿英 C 687.038 Ai Juan 艾涓 C 694.348 Ai Mi 艾米 C 694.522 Ai Qing = Jiang Haicheng 艾青 C 687.054 Ai Wei 艾偉 C 694.434 Ai Wen 艾雯 C 698.315 Ai Wu = Tang Daogeng 艾蕪 C 687.055 Anni Baobei 安妮寶貝 C 694.437 Ba Jin = Li Feigan 巴金 C 687.022 Ba Ren = Wang Renshu 巴人 C 687.057 Bai Hua 白樺 C 694.101 Bai Juyi (auch Bo Juyi) 白居易 C 568 Bai Lang 白郎 C 687.151 Bai Qiu 白萩 C 698.322 Bai Ren 白刃 C 694.063 Bai Wei 白危 C 687.155 Bai Wei 白蘶 C 687.204 Bai Xianyong 白先勇 C 698.002 Bai Xiaoguang = Ma Jia 白曉光 C 687.046 Bai Ye = Fei Qi 白夜 C 687.163 Bao Mi 保密 C 698.105 Bao Xiaolin 包曉琳 C 694.559 Bei Cun 北村 C 694.323 Bei Dao = Zhao Zhenkai 北島 C 694.237 Bi Feiyu 畢飛宇 C 694.358 Bi Shumin 畢淑敏 C 694.319 Bi Ye 碧野 C 694.145 Bian Zhilin 卞之琳 C 687.105 Bing Xin = Xie Wanying 冰心 C 687.023 Bo Yang 柏楊 C 698.083 Personenregister 1 Cai Chusheng 蔡楚生 C 694.200 Cai Qilan = Lu'ermen Yufu 蔡奇蘭 C 698.248 Cai Tianxin 蔡天新 C 694.526 Cai Yanpei 蔡炎培 C 698.293 Cai Yuanpei 蔡元培 C 687.083 Can Xue = Deng Xiaohua 殘雪 C 694.246 Cang Langke 滄浪客 C 698.113 Cao Cao 曹操 C 544 Cao Guilin = Glen Cao 曹桂林 C 694.364 Cao Juren 曹聚仁 C 687.042 Cao Lijuan 曹麗娟 C 698.205 Cao Ming 草明 C 687.078 Cao Naiqian 曹乃謙 C 694.580 Cao Pi 曹丕 C 544 Cao Wenxuan 曹文軒 C 694.334 Cao Xueqin 曹雪芹 C 676 Cao Yu 曹禺 C 687.034 Cao Zhenglu 曹征路 C 694.576 Cao Zhi 曹植 C 544 Cao Zhuanmei = Du Ai 曹傳美 C 687.131 Cen Sang 岑桑 C 694.083 Cha Liangzheng = Mu Dan 查良錚 C 687.196 Chang Yao = Wang Changyao 昌耀 C 694.299 Chen Baichen -

Red Discipline

Red Discipline A Shandong Professor, Honglou meng, and the Rewriting of Literary History in the Early P.R.C. Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades am Fachbereich Geschichts- und Kulturwissenschaften der Freien Universität Berlin November 2012 vorgelegt von Marie-Theres Strauss aus Stuttgart Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades am Fachbereich Geschichts- und Kulturwissenschaften der Freien Universität Berlin November 2012 vorgelegt von Marie-Theres Strauss aus Stuttgart 1. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Erling von Mende 2. Gutacher: PD Dr. Ingo Schäfer Datum der Disputation: 25. Juni 2013 RED DISCIPLINE Table of Contents List of Abbreviations ...................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................... 2 Chapter One. A Shandong Professor ..................................................................................................... 13 1. The Problem of Sources ............................................................................................................... 15 2. The Problem of Narratives ......................................................................................................... 25 3. A Republican Education ............................................................................................................... 29 4. A Socialist Profession