Reading Hong Kong Literature from the Periphery of Modern Chinese Literature : Liu Yichang Studies As an Example = 從現代中 國文學的邊缘看香港文學研究 : 以劉以鬯研究為例

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hong Kong Literature As Sinophone Literature = È'¯Èªžèªžç³

Journal of Modern Literature in Chinese 現代中文文學學報 Volume 8 Issue 2 Vol. 8.2 & 9.1 八卷二期及九卷一期 Article 2 (2008) 1-1-2008 Hong Kong literature as Sinophone literature = 華語語系香港文學 初論 Shu Mei SHIH University of California, Los Angeles Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.ln.edu.hk/jmlc Recommended Citation Shih, S.-m. (2008). Hong Kong literature as Sinophone literature = 華語語系香港文學初論. Journal of Modern Literature in Chinese, 8.2&9.1, 12-18. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Centre for Humanities Research 人文學科研究中心 at Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Modern Literature in Chinese 現代中文文學學報 by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. Hong Kong Literature as Sinophone Literature 華語語系香港文學初論 史書美 SHIH Shu-mei 加州大學洛杉磯分校亞洲語言文化系、 亞美研究系及比較文學系 Department of Comparative Literature, Asian Languages and Cultures, and Asian American Studies, University of California, Los Angeles A denotative meaning of the term “Sinophone,” as used by Sau-ling Wong in her work on Sinophone Chinese American literature to designate Chinese American literature written in Sinitic languages, is a productive way to start the investigation of the notion in terms of its connotative meanings.1 2 Connotation, by dictionary definition, is the practice that implies other characteristics and meanings beyond the term’s denotative meaning; ideas and feelings invoked in excess of the literal meaning; and, as a philosophical practice, the practice of identifying certain determining principles underlying the implied and invoked meanings, characteristics, ideas, and feelings. This short essay is a preliminary exploration of the connotative meanings of the category that I call Sinophone Hong Kong literature vis-a-vis the emergent field of Sinophone'studies as the study of Sinitic-language cultures, communities, and histories on the margins of China and Chineseness. -

The Literature of China in the Twentieth Century

BONNIE S. MCDOUGALL KA此1 LOUIE The Literature of China in the Twentieth Century 陪詞 Hong Kong University Press 挫芋臨眷戀犬,晶 lll 聶士 --「…- pb HOMAMnEPgUimmm nrRgnIWJM inαJ m1ιLOEbq HHny可 rryb的問可c3 們 unn 品 Fb 心 油 β 7 叫 J『 。 Bonnie McDougall and Kam Louie, 1997 ISBN 962 209 4449 First published in the United Kingdom in 1997 by C. Hurst & Co. (Publishers) Ltd. This soft cover edition published in 1997 by Hong Kong University Press is available in Hong Kong, China and Taiwan All righ臼 reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher. Printed in England CONTENTS Acknowledgements page v Chapters 1. Introduction 1 Part I. 1900-1937 2. Towards a New Culture 13 3. Poetry: The Transformation of the Past 31 4. Fiction: The Narrative Subject 82 5. Drama: Writing Performance 153 Part II. 1938-1965 6. Return to Tradition 189 7. Fiction: Searching for Typicality 208 8. Poetry: The Challenge of Popularisation 261 9. Drama: Performing for Politics 285 Part III. 1966-1989 10. The Reassertion of Modernity 325 11. Drama: Revolution and Reform 345 12. Fiction: Exploring Alternatives 368 13. Poe世y: The Challenge of Modernity 421 14. Conclusion 441 Further Reading 449 Glossary of Titles 463 Index 495 Vll INTRODUCTION Classical Chinese poet可 and the great traditional novels are widely admired by readers throughout the world. Chinese literature in this centu可 has not yet received similar acclaim. -

Chinese Literature in the Second Half of a Modern Century: a Critical Survey

CHINESE LITERATURE IN THE SECOND HALF OF A MODERN CENTURY A CRITICAL SURVEY Edited by PANG-YUAN CHI and DAVID DER-WEI WANG INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS • BLOOMINGTON AND INDIANAPOLIS William Tay’s “Colonialism, the Cold War Era, and Marginal Space: The Existential Condition of Five Decades of Hong Kong Literature,” Li Tuo’s “Resistance to Modernity: Reflections on Mainland Chinese Literary Criticism in the 1980s,” and Michelle Yeh’s “Death of the Poet: Poetry and Society in Contemporary China and Taiwan” first ap- peared in the special issue “Contemporary Chinese Literature: Crossing the Bound- aries” (edited by Yvonne Chang) of Literature East and West (1995). Jeffrey Kinkley’s “A Bibliographic Survey of Publications on Chinese Literature in Translation from 1949 to 1999” first appeared in Choice (April 1994; copyright by the American Library Associ- ation). All of the essays have been revised for this volume. This book is a publication of Indiana University Press 601 North Morton Street Bloomington, IN 47404-3797 USA http://www.indiana.edu/~iupress Telephone orders 800-842-6796 Fax orders 812-855-7931 Orders by e-mail [email protected] © 2000 by David D. W. Wang All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses’ Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences— Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. -

ABSTRACT Title of Document: the ANTI-CONFUCIAN CAMPAIGN

ABSTRACT Title of Document: THE ANTI-CONFUCIAN CAMPAIGN DURING THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION, AUGUST 1966-JANUARY 1967 Zehao Zhou, Doctor of Philosophy, 2011 Directed By: Professor James Gao, Department of History This dissertation examines the attacks on the Three Kong Sites (Confucius Temple, Confucius Mansion, Confucius Cemetery) in Confucius’s birthplace Qufu, Shandong Province at the start of the Cultural Revolution. During the height of the campaign against the Four Olds in August 1966, Qufu’s local Red Guards attempted to raid the Three Kong Sites but failed. In November 1966, Beijing Red Guards came to Qufu and succeeded in attacking the Three Kong Sites and leveling Confucius’s tomb. In January 1967, Qufu peasants thoroughly plundered the Confucius Cemetery for buried treasures. This case study takes into consideration all related participants and circumstances and explores the complicated events that interwove dictatorship with anarchy, physical violence with ideological abuse, party conspiracy with mass mobilization, cultural destruction with revolutionary indo ctrination, ideological vandalism with acquisitive vandalism, and state violence with popular violence. This study argues that the violence against the Three Kong Sites was not a typical episode of the campaign against the Four Olds with outside Red Guards as the principal actors but a complex process involving multiple players, intraparty strife, Red Guard factionalism, bureaucratic plight, peasant opportunism, social ecology, and ever- evolving state-society relations. This study also maintains that Qufu locals’ initial protection of the Three Kong Sites and resistance to the Red Guards were driven more by their bureaucratic obligations and self-interest rather than by their pride in their cultural heritage. -

Destination Hong Kong: Negotiating Locality in Hong Kong Novels 1945-1966 Xianmin Shen University of South Carolina - Columbia

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2015 Destination Hong Kong: Negotiating Locality in Hong Kong Novels 1945-1966 Xianmin Shen University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Shen, X.(2015). Destination Hong Kong: Negotiating Locality in Hong Kong Novels 1945-1966. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/3190 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DESTINATION HONG KONG: NEGOTIATING LOCALITY IN HONG KONG NOVELS 1945-1966 by Xianmin Shen Bachelor of Arts Tsinghua University, 2007 Master of Philosophy of Arts Hong Kong Baptist University, 2010 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2015 Accepted by: Jie Guo, Major Professor Michael Gibbs Hill, Committee Member Krista Van Fleit Hang, Committee Member Katherine Adams, Committee Member Lacy Ford, Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Xianmin Shen, 2015 All Rights Reserved. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Several institutes and individuals have provided financial, physical, and academic supports that contributed to the completion of this dissertation. First the Department of Literatures, Languages, and Cultures at the University of South Carolina have supported this study by providing graduate assistantship. The Carroll T. and Edward B. Cantey, Jr. Bicentennial Fellowship in Liberal Arts and the Ceny Fellowship have also provided financial support for my research in Hong Kong in July 2013. -

Li Ling Ngan

Beyond Cantonese: Articulation, Narrative and Memory in Contemporary Sinophone Hong Kong, Singaporean and Malaysian Literature by Li Ling Ngan A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of East Asian Studies University of Alberta © Li Ling Ngan, 2019 Abstract This thesis examines Cantonese in Sinophone literature, and the time- and place- specific memories of Cantonese speaking communities in Hong Kong, Singapore, and Malaysia after the year 2000. Focusing on the literary works by Wong Bik-wan (1961-), Yeng Pway Ngon (1947-) and Li Zishu (1971-), this research demonstrates how these three writers use Cantonese as a conduit to evoke specific memories in order to reflect their current identity. Cantonese narratives generate uniquely Sinophone critique in and of their respective places. This thesis begins by examining Cantonese literature through the methodological frameworks of Sinophone studies and memory studies. Chapter One focuses on Hong Kong writer Wong Bik-wan’s work Children of Darkness and analyzes how vulgar Cantonese connects with involuntary autobiographical memory and the relocation of the lost self. Chapter Two looks at Opera Costume by Singaporean writer Yeng Pway Ngon and how losing connection with one’s mother tongue can lose one’s connection with their familial memories. Chapter Three analyzes Malaysian writer Li Zishu’s short story Snapshots of Chow Fu and how quotidian Cantonese simultaneously engenders crisis of memory and the rejection of the duty to remember. These works demonstrate how Cantonese, memory, and identity, are transnationally linked in space and time. This thesis concludes with thinking about the future direction of Cantonese cultural production. -

Veda Publishing House of the Slovak Academy of Sciences Slovak Academy of Sciences

VEDA PUBLISHING HOUSE OF THE SLOVAK ACADEMY OF SCIENCES SLOVAK ACADEMY OF SCIENCES INSTITUTE OF LITERARY SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF ORIENTAL STUDIES EDITORS JOZEF GENZOR VIKTOR KRUPA ASIAN AND AFRICAN STUDIES SLOVAK ACADEMY OF SCIENCES BRATISLAVA INSTITUTE OF LITERARY SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF ORIENTAL STUDIES XXIII 1987 1988 VEDA, PUBLISHING HOUSE OF THE SLOVAK ACADEMY OF SCIENCES • BRATISLAVA CURZON PRESS • LONDON PUBLISHED OUTSIDE THE SOCIALIST COUNTRIES SOLELY BY CURZON PRESS LTD • LONDON ISBN 0 7007 0211 3 ISBN 0571 2 7 4 2 © VEDA, VYDAVATEĽSTVO SLOVENSKEJ AKADÉMIE VIED, 1988 CONTENTS A rtic le s G á I i k, Marián: Some Remarks on the Process of Emancipation in Modern Asian and African Literatures ................................................................................................................... 9 G ru ner, Fritz: Some Remarks on Developmental Tendencies in Chinese Contempo rary Literature since 1979 ....................................................................................................... 31 Doležalová, Anna: New Qualities in Contemporary Chinese Stories (1979 — Early 1 9 8 0 s ).................................................................................................................................. 45 Kalvodová, Dana: Time and Space Relations in Kong Shangren's Drama The Peach Blossom Fan ........................................................................................................................... 69 Kuťka, Karol: Some Reflections on the Atomic Bomb Literature and Literature on the Atomic -

University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Film Studies Hong Kong Cinema Since 1997: The Response of Filmmakers Following the Political Handover from Britain to the People’s Republic of China by Sherry Xiaorui Xu Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2012 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Film Studies Doctor of Philosophy HONG KONG CINEMA SINCE 1997: THE RESPONSE OF FILMMAKERS FOLLOWING THE POLITICAL HANDOVER FROM BRITAIN TO THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA by Sherry Xiaorui Xu This thesis was instigated through a consideration of the views held by many film scholars who predicted that the political handover that took place on the July 1 1997, whereby Hong Kong was returned to the sovereignty of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) from British colonial rule, would result in the “end” of Hong Kong cinema. -

Research Assessment Exercise 2020 Impact Case Study University: The

Research Assessment Exercise 2020 Impact Case Study University: The Chinese University of Hong Kong Unit of Assessment (UoA): 30 Title of case study: Promoting Public Awareness and Respect in Hong Kong Literature through the Endowment of Prof Lo Wai Luen (Xiao Si) (1) Summary of the impact (indicative maximum 100 words) Prof Lo Wai Luen’s research has been instrumental in establishing and re-evaluating the literary legacy of Hong Kong literature. Lo’s editorial scholarship and investigative research on early works and writers, including the breakthrough discovery of ‘literary landscapes’, has provided new perspectives on the cultural mobility of one of the most vibrant cosmopolitans in the world. Via Lo’s new, definitive editions, biographical and oral historical publications, online archives and public lectures, Hong Kong literature has reached new global audiences and through the reconfigured insights have enhanced public awareness and respect in one’s own culture. (2) Underpinning research (indicative maximum 500 words) Prof Lo’s research on Hong Kong literature spans her entire period of employment at CUHK (1979-2002; emeritus 2002-present) and covers two main areas: (i) the scholarly editing of early literary works and documents; (ii) investigations of the literary field of Hong Kong, including the restoration of previously unknown or missing texts. Lo was the first scholar to give Hong Kong’s often fragmented literary productions the level of attention they deserve and to consolidate its importance as one of the seminal intellectual forces of twentieth century culture. The significance of Hong Kong literature reaches well beyond the literary sphere into questions of political and social organisation, national identity and the role of the intellectual, and Lo’s work highlights the importance of Hong Kong literature in each of these spheres. -

Cultural Revolution

Chinese Fiction of the Cultural Revolution Lan Yang -w~*-~:tItB.~±. HONG KONG UNIVERSITY PRESS Hong Kong University Press 14/F Hing Wai Centre 7 Tin Wan Praya Road Aberdeen, Hong Kong © Hong Kong University Press 1998 ISBN 962 209 467 8 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in Hong Kong by Caritas Printing Training Centre. Contents List of Tables ix Foreword xi Preface xiii Introduction 1 • CR novels and CR agricultural novels 3 • Literary Policy and Theory in the Cultural Revolution 14 Part I Characterization of the Main Heroes 33 Introduction to Part I 35 1. Personal Background 39 2. Physical Qualities 49 • Strong Constitution and Vigorous Air 50 • Unsophisticated Features and Expression 51 • Dignified Manner and Awe~ Inspiring Bearing 52 • Big and Bright Piercing Eyes 53 • A Sonorous and Forceful Voice 53 vi • Contents 3. Ideological Qualities 61 • Consciousness of Class, Road and Line Struggles 61 • Consciousness of Altruism and Collectivism 66 4. Temperamental and Behavioural Qualities 75 • Categories of Temperamental and Behavioural Qualities 75 • Social and Cultural Foundations of Temperamental and Behavioural Qualities 88 5. Prominence Given to the Main Heroes 97 • Practice of the 'Three Prominences' 97 • Other Stock Points Concerning Prominence of the Main Heroes 118 Part II Lexical Style 121 Introduction to Part II 123 • Selection of the Sample 124 • Units and Levels of Analysis 125 • Categories of Stylistic Items versus References 127 • Exhaustive or Sample Measurement 128 • The Statistical Process 128 6. -

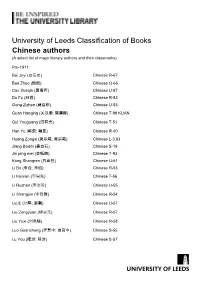

University of Leeds Classification of Books Chinese Authors (A Select List of Major Literary Authors and Their Classmarks)

University of Leeds Classification of Books Chinese authors (A select list of major literary authors and their classmarks) Pre-1911: Bai Juyi (白居易) Chinese R-67 Bao Zhao (鮑照) Chinese Q-66 Cao Xueqin (曹雪芹) Chinese U-87 Du Fu (杜甫) Chinese R-83 Gong Zizhen (龔自珍) Chinese U-53 Guan Hanqing (关汉卿; 關漢卿) Chinese T-99 KUAN Gui Youguang (归有光) Chinese T-51 Han Yu (韩愈; 韓愈) Chinese R-40 Huang Zongxi (黄宗羲; 黃宗羲) Chinese L-3.83 Jiang Baishi (姜白石) Chinese S-19 Jin ping mei (金瓶梅) Chinese T-93 Kong Shangren (孔尚任) Chinese U-51 Li Bo (李白; 李伯) Chinese R-53 Li Kaixian (李開先) Chinese T-56 Li Ruzhen (李汝珍) Chinese U-55 Li Shangyin (李商隱) Chinese R-54 Liu E (刘鹗; 劉鶚) Chinese U-57 Liu Zongyuan (柳宗元) Chinese R-57 Liu Yuxi (刘禹锡) Chinese R-58 Luo Guanzhong (罗贯中; 羅貫中) Chinese S-55 Lu You (陆游; 陸游) Chinese S-57 Ma Zhiyuan (马致远; 馬致遠) Chinese T-59 Meng Haoran (孟浩然) Chinese R-60 Ouyang Xiu (欧阳修; 歐陽修) Chinese S-64 Pu Songling (蒲松龄; 蒲松齡) Chinese U-70 Qu Yuan (屈原) Chinese Q-20 Ruan Ji (阮籍) Chinese Q-50 Shui hu zhuan (水浒传; 水滸傳) Chinese T-75 Su Manshu (苏曼殊; 蘇曼殊) Chinese U-99 SU Su Shi (苏轼; 蘇軾) Chinese S-78 Tang Xianzu (汤显祖; 湯顯祖) Chinese T-80 Tao Qian (陶潛) Chinese Q-81 Wang Anshi (王安石) Chinese S-89 Wang Shifu (王實甫) Chinese S-90 Wang Shizhen (王世貞) Chinese T-92 Wu Cheng’en (吳承恩) Chinese T-99 WU Wu Jingzi (吴敬梓; 吳敬梓) Chinese U-91 Wang Wei (王维; 王維) Chinese R-90 Ye Shi (叶适; 葉適) Chinese S-96 Yu Xin (庾信) Chinese Q-97 Yuan Mei (袁枚) Chinese U-96 Yuan Zhen (元稹) Chinese R-96 Zhang Juzheng (張居正) Chinese T-19 After 1911: [The catalogue should be used to verify classmarks in view of the on-going -

The Compendium of Hong Kong Literature 1919-1949

Research Assessment Exercise 2020 Impact Case Study University: The Education University of Hong Kong Unit of Assessment (UoA): 30 Chinese language & literature Title of case study: The Compendium of Hong Kong Literature 1919-1949 (1) Summary of the impact This study describes the reception and impact of the project of The Compendium of Hong Kong Literature 1919-1949 (The Compendium), reviewing the major cultural contributions of The Compendium made to the general public significantly beyond academia, including the local and overseas non-academic institutional and governmental recognitions, media coverage of all kinds, educational influence, and the huge reach the project created in its wealth of post-publication events held in a variety of venues in Hong Kong and overseas. The far-reaching impacts of The Compendium feature prominently in their contribution to cultural preservation, education, public memorialisation, regional cultural exchange, and tourism. (2) Underpinning research The idea of compiling a compendium of Hong Kong literature dates back to as early as the 1980s but was not materialised due to the lack of manpower and resource. In 2009, Prof Leonard Chan Kwok- kou and Dr Chan Chi-tak brought up the idea again, officially and systematically embarking on its realisation. Taking the Compendia of Chinese New Literature (Shanghai, 1935) as the prime predecessor, an editorial committee consisting of local literary specialists was subsequently formed and the project of “The Compendium of Hong Kong Literature” launched. In view of the daunting sea of literary works, the first series of the project as reported here focuses on the period of 1919- 1949. The twelve-volume Compendium is a landmark in Hong Kong literary studies and a much- awaited showcase of Hong Kong literature as a body of literary works that should be considered in its own right.