Chinese Face/Off

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hongkong a Study in Economic Freedom

HongKOng A Study In Economic Freedom Alvin Rabushka Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace Stanford University The 1976-77 William H. Abbott Lectures in International Business and Economics The University of Chicago • Graduate School of Business © 1979 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. ISBN 0-918584-02-7 Contents Preface and Acknowledgements vn I. The Evolution of a Free Society 1 The Market Economy 2 The Colony and Its People 10 Resources 12 An Economic History: 1841-Present 16 The Political Geography of Hong Kong 20 The Mother Country 21 The Chinese Connection 24 The Local People 26 The Open Economy 28 Summary 29 II. Politics and Economic Freedom 31 The Beginnings of Economic Freedom 32 Colonial Regulation 34 Constitutional and Administrative Framework 36 Bureaucratic Administration 39 The Secretariat 39 The Finance Branch 40 The Financial Secretary 42 Economic and Budgetary Policy 43 v Economic Policy 44 Capital Movements 44 Subsidies 45 Government Economic Services 46 Budgetary Policy 51 Government Reserves 54 Taxation 55 Monetary System 5 6 Role of Public Policy 61 Summary 64 III. Doing Business in Hong Kong 67 Location 68 General Business Requirements 68 Taxation 70 Employment and Labor Unions 74 Manufacturing 77 Banking and Finance 80 Some Personal Observations 82 IV. Is Hong Kong Unique? Its Future and Some General Observations about Economic Freedom 87 The Future of Hong Kong 88 Some Preliminary Observations on Free-Trade Economies 101 Historical Instances of Economic Freedom 102 Delos 103 Fairs and Fair Towns: Antwerp 108 Livorno 114 The Early British Mediterranean Empire: Gibraltar, Malta, and the Ionian Islands 116 A Preliminary Thesis of Economic Freedom 121 Notes 123 Vt Preface and Acknowledgments Shortly after the August 1976 meeting of the Mont Pelerin Society, held in St. -

Icons, Culture and Collective Identity of Postwar Hong Kong

Intercultural Communication Studies XXII: 1 (2013) R. MAK & C. CHAN Icons, Culture and Collective Identity of Postwar Hong Kong Ricardo K. S. MAK & Catherine S. CHAN Hong Kong Baptist University, Hong Kong S.A.R., China Abstract: Icons, which take the form of images, artifacts, landmarks, or fictional figures, represent mounds of meaning stuck in the collective unconsciousness of different communities. Icons are shortcuts to values, identity or feelings that their users collectively share and treasure. Through the concrete identification and analysis of icons of post-war Hong Kong, this paper attempts to highlight not only Hong Kong people’s changing collective needs and mental or material hunger, but also their continuous search for identity. Keywords: Icons, Hong Kong, Hong Kong Chinese, 1997, values, identity, lifestyle, business, popular culture, fusion, hybridity, colonialism, economic takeoff, consumerism, show business 1. Introduction: Telling Hong Kong’s Story through Icons It seems easy to tell the story of post-war Hong Kong. If merely delineating the sky-high synopsis of the city, the ups and downs, high highs and low lows are at once evidently remarkable: a collective struggle for survival in the post-war years, tremendous social instability in the 1960s, industrial take-off in the 1970s, a growth in economic confidence and cultural arrogance in the 1980s and a rich cultural upheaval in search of locality before the handover. The early 21st century might as well sum up the development of Hong Kong, whose history is long yet surprisingly short- propelled by capitalism, gnawing away at globalization and living off its elastic schizophrenia. -

The Status of Cantonese in the Education Policy of Hong Kong Kwai Sang Lee and Wai Mun Leung*

Lee and Leung Multilingual Education 2012, 2:2 http://www.multilingual-education.com/2/1/2 RESEARCH Open Access The status of Cantonese in the education policy of Hong Kong Kwai Sang Lee and Wai Mun Leung* * Correspondence: waimun@ied. Abstract edu.hk Department of Chinese, The Hong After the handover of Hong Kong to China, a first-ever policy of “bi-literacy and Kong Institute of Education, Hong tri-lingualism” was put forward by the Special Administrative Region Government. Kong Under the trilingual policy, Cantonese, the most dominant local language, equally shares the official status with Putonghua and English only in name but not in spirit, as neither the promotion nor the funding approaches on Cantonese match its legal status. This paper reviews the status of Cantonese in Hong Kong under this policy with respect to the levels of government, education and curriculum, considers the consequences of neglecting Cantonese in the school curriculum, and discusses the importance of large-scale surveys for language policymaking. Keywords: the status of Cantonese, “bi-literacy and tri-lingualism” policy, language survey, Cantonese language education Background The adjustment of the language policy is a common phenomenon in post-colonial societies. It always results in raising the status of the regional vernacular, but the lan- guage of the ex-colonist still maintains a very strong influence on certain domains. Taking Singapore as an example, English became the dominant language in the work- place and families, and the local dialects were suppressed. It led to the degrading of both English and Chinese proficiency levels according to scholars’ evaluation (Goh 2009a, b). -

Hong Kong 20 Ans / 20 Films Rétrospective 20 Septembre - 11 Octobre

HONG KONG 20 ANS / 20 FILMS RÉTROSPECTIVE 20 SEPTEMBRE - 11 OCTOBRE À L’OCCASION DU 20e ANNIVERSAIRE DE LA RÉTROCESSION DE HONG KONG À LA CHINE CO-PRÉSENTÉ AVEC CREATE HONG KONG 36Infernal affairs CREATIVE VISIONS : HONG KONG CINEMA, 1997 – 2017 20 ANS DE CINÉMA À HONG KONG Avec la Cinémathèque, nous avons conçu une programmation destinée à célé- brer deux décennies de cinéma hongkongais. La période a connu un rétablis- sement économique et la consécration de plusieurs cinéastes dont la carrière est née durant les années 1990, sans compter la naissance d’une nouvelle génération d’auteurs. PERSISTANCE DE LA NOUVELLE VAGUE Notre sélection rend hommage à la créativité persistante des cinéastes de Hong Kong et au mariage improbable de deux tendances complémentaires : l’ambitieuse Nouvelle Vague artistique et le film d’action des années 1980. Bien qu’elle soit exclue de notre sélection, il est utile d’insister sur le fait que la production chinoise 20 ANS / FILMS KONG, HONG de cinéastes et de vedettes originaires de Hong Kong, tels que Jackie Chan, Donnie Yen, Stephen Chow et Tsui Hark, continue à caracoler en tête du box-office chinois. Les deux films Journey to the West avec Stephen Chow (le deuxième réalisé par Tsui Hark) et La Sirène (avec Stephen Chow également) ont connu un immense succès en République Populaire. Ils n’auraient pas été possibles sans l’œuvre antérieure de leurs auteurs, sans la souplesse formelle qui caractérise le cinéma de Hong Kong. L’histoire et l’avenir de l’industrie hongkongaise se lit clairement dans la carrière d’un pionnier de la Nouvelle Vague, Tsui Hark, qui a rodé son savoir-faire en matière d’effets spéciaux d’arts martiaux dans ses premières productions télévisuelles et cinématographiques à Hong Kong durant les années 70 et 80. -

Semifinalists to Face Off for Beef Loving Texans' Best Butcher in Texas

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Sarah Flores, Hahn Public for Texas Beef Council 512-344-2045 [email protected] SEMIFINALISTS TO FACE OFF FOR BEEF LOVING TEXANS’ BEST BUTCHER IN TEXAS Texas Beef Council Selects Competitors to Battle for Coveted Finalist Spots AUSTIN, Texas – Feb. 23, 2017 –Texas Beef Council announces the top Semifinalists who will move on to compete in the Beef Loving Texans’ Best Butcher in Texas regional competition. The challenge, which pits butchers from across Texas against each other for the chance to win cash prizes and the esteemed title of Beef Loving Texans’ Best Butcher in Texas, has brought some of the state’s most talented butchers together – representing an art form that has been important to Texas’ cultural heritage. Regional semifinal rounds will be held throughout the state in Houston on March 4, Dallas on March 18 and San Antonio on April 1. In each city, Semifinalists will partake in a three-part challenge, which tests competitors on cut identification, along with their skills to cut to order and cut beef for retail merchandising. Each competitor will be equipped with Victorinox Swiss Army boning knives, a breaking knife, a cut resistant glove, a steel and a knife roll, to ensure everyone starts on an even playing field. Competitors will receive top marks based on their technique, creativity, presentation and consumer interaction. With culinary influencer/personality Jess Pryles emceeing, top industry professionals and culinary experts will weigh in in each region to determine the top three competitors who will move on to the final round at the Austin Food + Wine Festival on April 29. -

Bullet in the Head

JOHN WOO’S Bullet in the Head Tony Williams Hong Kong University Press The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © Tony Williams 2009 ISBN 978-962-209-968-5 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Condor Production Ltd., Hong Kong, China Contents Series Preface ix Acknowledgements xiii 1 The Apocalyptic Moment of Bullet in the Head 1 2 Bullet in the Head 23 3 Aftermath 99 Appendix 109 Notes 113 Credits 127 Filmography 129 1 The Apocalyptic Moment of Bullet in the Head Like many Hong Kong films of the 1980s and 90s, John Woo’s Bullet in the Head contains grim forebodings then held by the former colony concerning its return to Mainland China in 1997. Despite the break from Maoism following the fall of the Gang of Four and Deng Xiaoping’s movement towards capitalist modernization, the brutal events of Tiananmen Square caused great concern for a territory facing many changes in the near future. Even before these disturbing events Hong Kong’s imminent return to a motherland with a different dialect and social customs evoked insecurity on the part of a population still remembering the violent events of the Cultural Revolution as well as the Maoist- inspired riots that affected the colony in 1967. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

Lesson 1: Would You Like to Go to Hong Kong?

Key Stage 1-2: Hong Kong Lesson 1: Would you like to go to Hong Kong? This lesson will enable students to learn about concepts of scale, location and direction through maps of the journey to Hong Kong from their own location. Locational Knowledge Place Knowledge Key questions and ideas Teaching and learning activities Resources Knowledge of major continental Pupils consider how we - Where is London/Hong Starter Downloads land masses and oceans. travel between different Kong? Read the letter on the PowerPoint Would you like to travel to Hong Knowledge of globally places, and how the - Which countries do presentation inviting the pupils to travel to Kong? (PPT) significant cities and the characteristics of a place you fly over when Hong Kong, and pose the questions Lesson Plan PDF | MSWORD highest mountain range in the determine how we travel travelling by aeroplane World map: flight path from included in the lesson plan such as ‘which world. there. from London to Hong London to Hong Kong PDF | Continents and Oceans Kong? countries will you need to fly over?’ MSWORD Hong Kong is a significant city Europe, Asia, North Sea, - What is a city? What is Pupils use the globe, world map and/or in the world which will allow Pacific Ocean a country and what is a Google Maps or Earth to help them. Additional Resources students to learn about the North America, Atlantic continent? How do Globe location of continents - Europe Ocean they compare? Main Teaching World map and Asia, the location of major Countries - What is the difference Use the PowerPoint presentation to guide Atlas for each table or talk countries such as China and United Kingdom, China between an ocean and partner pair pupils through the journey they would take Russia, the location of major Cities a sea? Google Maps/ Earth (on mountain ranges – the London, Hong Kong - Which geographical if they travelled to Hong Kong. -

Representation of Females As Victims in Hong Kong Crime Films (2003-2015)

REPRESENTATION OF FEMALES AS VICTIMS IN HONG KONG CRIME FILMS (2003-2015) Perspectives from One Nite in Mongkok, Protégé and The Stool Pigeon TINGTING HU (胡婷婷) MA. Media, Loughborough University, UK, 2011 BA. Arts, Shanghai Theatre Academy, China, 2010 This thesis is submitted for the degree of Master of Research Department of Media, Music, Communication and Cultural Studies Faculty of Arts Macquarie University, Sydney December 25, 2015 MRES Thesis 2015 Tingting HU (ID: 43765858) TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................................ iii CERTIFICATE OF AUTHORSHIP/ORIGINALITY .................................................. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................. v CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER 2 FEMINISM AND HONG KONG CRIME FILMS ................................. 7 Feminism and Film Studies .................................................................................................. 7 The Western Context ......................................................................................................... 7 The Chinese Context ....................................................................................................... 11 Crime Films and Violence Against Women ....................................................................... 15 Crime Films ................................................................................................................... -

Rumble in the Bronx Download Torrent Rumble in the Bronx

rumble in the bronx download torrent Rumble in the Bronx. A young man visiting and helping his uncle in New York City finds himself forced to fight a street gang and the mob with his martial art skills. Keong comes from Hong Kong to visit New York for his uncle's wedding. His uncle runs a market in the Bronx and Keong offers to help out while Uncle is on his honeymoon. During his stay in the Bronx, Keong befriends a neighbor kid and beats up some neighborhood thugs who cause problems at the market. Meanwhile, one of those petty thugs in the local gang stumbles into a criminal situation way over his head. Blinded by greed, his involvement draws his gang, the kid, Keong, and the whole neighborhood into a deadly crossfire. When the lazy cops fail to successfully resolve matters, Keong takes things into his own hands. Needless to say, much spectacular kung-fu and outrageous action sequences follow. Downloaded 15689 times 5/12/2017 12:26:07 AM. Download Torrent "Terremoto nel Bronx- Rumble in the Bronx (1995) ITA-ENG Ac3 5.1 SD H264 sub. " Titolo originale Hung fan kui Titolo internazionale Rumble in the Bronx Data di uscita 29 Agosto 1996 (Italia), 21 Gennaio 1995 (Hong Kong) Genere Commedia , Poliziesco , Thriller Anno 1995 Regia Stanley Tong Paese Canada, Hong Kong Durata 87 Min. Jackie Chan, Anita Mui, Françoise Yip, Bill Tung, Marc Akerstream, Garvin Cross, Morgan Lam, Carrie Cain-Sparks, Alecia Paget. Invitato a recarsi negli Stati Uniti per via di un matrimonio, un uomo riesce a portare sulla retta via una banda giovanile, rendendosi utile nello sconfiggere un boss mafioso. -

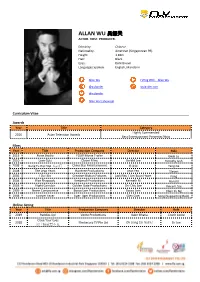

Allan Wu 吴振天 Actor

ALLAN WU 吴振天 ACTOR. HOST. PRODUCER. Ethnicity: Chinese Nationality: American (Singaporean PR) Height: 1.83m Hair: Black Eyes: Dark Brown Languages Spoken: English, Mandarin Allan Wu FLYing With... Allan Wu @wulander wulander.com @wulander Allan Wu's Showreel Curriculum Vitae Awards Year Title Category Highly Commended 2016 Asian Television Awards Best Entertainment Presenter/Host Films Year Title Production Company Director Role 2015 Poise Studio FOUR Movie Trailer Gwai Lo 2010 Love Cuts Clover Films Gerald Lee Timothy Goh 2008 Kung Fu Hip Hop 精武门 China Star Entertainment 傅华阳 Tang Ge 2008 The Leap Years Raintree Productions Jean Yeo Steven 2005 I Do I Do Creative Motion Pictures Jack Neo / Lim Boon Hwee Feng 2004 Rice Rhapsody Kenberoli Productions Kenneth Bi Ronald 2003 Night Corridor Golden Gate Productions Chi-Chiu Lee Vincent Sze 1999 Never Compromise Bosco Lam Productions Bosco Lam Chun Yu Ng 1998 Forever Fever Tiger Tiger Productions Glen Goei Seng (Supporting Role) Online Acting Year Title Production Company Director Role 2019 Paddles Up! Verite Productions Kabir Bhatia Coach Leslie Close Your Eyes 2018 Mediacorp TV Pte Ltd Oh Liang Cai 胡凉财 Dr Joe 闭上眼就看不见 Television Actor Year Title Production Company Director Role 2019 CLIF 5 Mediacorp TV Pte Ltd Oh Liang Cai Alexis 2018 Divided 分裂 Mediacorp TV Pte Ltd Lee Thean-jeen Inspector Wu Wenjie 2014 Mata Mata Season 2 MediaCorp TV Singapore Pte Ltd Alan Leong 2014 First Gear House Films Lead 2006 House Of Joy Mediacorp Studios Pte Ltd 罗温温 Zheng Sanji 2006 Xing Jing Er Ren Zhu Mediacorp -

Va.Orgjackie's MOVIES

Va.orgJACKIE'S MOVIES Jackie starred in his first movie at the age of eight and has been making movies ever since. Here's a list of Jackie's films: These are the films Jackie made as a child: ·Big and Little Wong Tin-Bar (1962) · The Lover Eternal (1963) · The Story of Qui Xiang Lin (1964) · Come Drink with Me (1966) · A Touch of Zen (1968) These are films where Jackie was a stuntman only: Fist of Fury (1971) Enter the Dragon (1973) The Himalayan (1975) Fantasy Mission Force (1982) Here is the complete list of all the rest of Jackie's movies: ·The Little Tiger of Canton (1971, also: Master with Cracked Fingers) · CAST : Jackie Chan (aka Chen Yuen Lung), Juan Hsao Ten, Shih Tien, Han Kyo Tsi · DIRECTOR : Chin Hsin · STUNT COORDINATOR : Chan Yuen Long, Se Fu Tsai · PRODUCER : Li Long Koon · The Heroine (1971, also: Kung Fu Girl) · CAST : Jackie Chan (aka Chen Yuen Lung), Cheng Pei-pei, James Tien, Jo Shishido · DIRECTOR : Lo Wei · STUNT COORDINATOR : Jackie Chan · Not Scared to Die (1973, also: Eagle's Shadow Fist) · CAST : Wang Qing, Lin Xiu, Jackie Chan (aka Chen Yuen Lung) · DIRECTOR : Zhu Wu · PRODUCER : Hoi Ling · WRITER : Su Lan · STUNT COORDINATOR : Jackie Chan · All in the Family (1975) · CAST : Linda Chu, Dean Shek, Samo Hung, Jackie Chan · DIRECTOR : Chan Mu · PRODUCER : Raymond Chow · WRITER : Ken Suma · Hand of Death (1976, also: Countdown in Kung Fu) · CAST : Dorian Tan, James Tien, Jackie Chan · DIRECTOR : John Woo · WRITER : John Woo · STUNT COORDINATOR : Samo Hung · New Fist of Fury (1976) · CAST : Jackie Chan, Nora Miao, Lo Wei, Han Ying Chieh, Chen King, Chan Sing · DIRECTOR : Lo Wei · STUNT COORDINATOR : Han Ying Chieh · Shaolin Wooden Men (1976) · CAST : Jackie Chan, Kam Kan, Simon Yuen, Lung Chung-erh · DIRECTOR : Lo Wei · WRITER : Chen Chi-hwa · STUNT COORDINATOR : Li Ming-wen, Jackie Chan · Killer Meteors (1977, also: Jackie Chan vs.