Why Has IPO Underpricing Increased Over Time?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NATIONAL IDENTITY in SCOTTISH and SWISS CHILDRENIS and YDUNG Pedplets BODKS: a CDMPARATIVE STUDY

NATIONAL IDENTITY IN SCOTTISH AND SWISS CHILDRENIS AND YDUNG PEDPLEtS BODKS: A CDMPARATIVE STUDY by Christine Soldan Raid Submitted for the degree of Ph. D* University of Edinburgh July 1985 CP FOR OeOeRo i. TABLE OF CONTENTS PART0N[ paos Preface iv Declaration vi Abstract vii 1, Introduction 1 2, The Overall View 31 3, The Oral Heritage 61 4* The Literary Tradition 90 PARTTW0 S. Comparison of selected pairs of books from as near 1870 and 1970 as proved possible 120 A* Everyday Life S*R, Crock ttp Clan Kellyp Smithp Elder & Cc, (London, 1: 96), 442 pages Oohanna Spyrip Heidi (Gothat 1881 & 1883)9 edition usadq Haidis Lehr- und Wanderjahre and Heidi kann brauchan, was as gelernt hatq ill, Tomi. Ungerar# , Buchklubg Ex Libris (ZOrichp 1980)9 255 and 185 pages Mollie Hunterv A Sound of Chariatst Hamish Hamilton (Londong 197ý), 242 pages Fritz Brunner, Feliy, ill, Klaus Brunnerv Grall Fi7soli (ZGricýt=970). 175 pages Back Summaries 174 Translations into English of passages quoted 182 Notes for SA 189 B. Fantasy 192 George MacDonaldgat týe Back of the North Wind (Londant 1871)t ill* Arthur Hughesp Octopus Books Ltd. (Londong 1979)t 292 pages Onkel Augusta Geschichtenbuch. chosen and adited by Otto von Grayerzf with six pictures by the authorg Verlag von A. Vogel (Winterthurt 1922)p 371 pages ii* page Alison Fel 1# The Grey Dancer, Collins (Londong 1981)q 89 pages Franz Hohlerg Tschipog ill* by Arthur Loosli (Darmstadt und Neuwaid, 1978)9 edition used Fischer Taschenbuchverlagg (Frankfurt a M99 1981)p 142 pages Book Summaries 247 Translations into English of passages quoted 255 Notes for 58 266 " Historical Fiction 271 RA. -

Chicago Board Options Exchange Annual Report 2001

01 Chicago Board Options Exchange Annual Report 2001 cv2 CBOE ‘01 01010101010101010 01010101010101010 01010101010101010 01010101010101010 01010101010101010 CBOE is the largest and 01010101010101010most successful options 01010101010101010marketplace in the world. 01010101010101010 01010101010101010 01010101010101010 01010101010101010 01010101010101010 01010101010101010ifc1 CBOE ‘01 ONE HAS OPPORTUNITIES The NUMBER ONE Options Exchange provides customers with a wide selection of products to achieve their unique investment goals. ONE HAS RESPONSIBILITIES The NUMBER ONE Options Exchange is responsible for representing the interests of its members and customers. Whether testifying before Congress, commenting on proposed legislation or working with the Securities and Exchange Commission on finalizing regulations, the CBOE weighs in on behalf of options users everywhere. As an advocate for informed investing, CBOE offers a wide array of educational vehicles, all targeted at educating investors about the use of options as an effective risk management tool. ONE HAS RESOURCES The NUMBER ONE Options Exchange offers a wide variety of resources beginning with a large community of traders who are the most experienced, highly-skilled, well-capitalized liquidity providers in the options arena. In addition, CBOE has a unique, sophisticated hybrid trading floor that facilitates efficient trading. 01 CBOE ‘01 2 CBOE ‘01 “ TO BE THE LEADING MARKETPLACE FOR FINANCIAL DERIVATIVE PRODUCTS, WITH FAIR AND EFFICIENT MARKETS CHARACTERIZED BY DEPTH, LIQUIDITY AND BEST EXECUTION OF PARTICIPANT ORDERS.” CBOE MISSION LETTER FROM THE OFFICE OF THE CHAIRMAN Unprecedented challenges and a need for strategic agility characterized a positive but demanding year in the overall options marketplace. The Chicago Board Options Exchange ® (CBOE®) enjoyed a record-breaking fiscal year, with a 2.2% growth in contracts traded when compared to Fiscal Year 2000, also a record-breaker. -

Erinnerungen Und Briefe

Diese PDF-Datei ist ein Teil von Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall: Erinnerungen und Briefe Version 1 2011.07 Briefe von 1790 bis Ende 1819 – 3 Bände, Graz 2011 Herausgegeben von Walter Höflechner und Alexandra Wagner Das Gesamtwerk findet sich unter: http://gams.uni-graz.at/hp – 1588 – 2 BRIEFLISTEN Zu den Brieflisten ist zu bemerken, dass die Namen der SchreiberInnen nicht bearbeiteter Briefe in der Regel – wohl auch jener bei BACHOFEN-ECHT – auf Grundlage der Briefunterschriften eruiert wurden und dass in diesem Umstand ein Unsicherheitsfaktor gegeben ist, der bedacht sein will. Dies betrifft natürlich auch die Zuweisung eines Familiennamens an ein bestimmtes Individuum innerhalb dieser Familie, was insbesondere beim Adel problematisch sein kann. Festzuhalten ist weiters, dass die Anzahl der Briefe, wie sie bei BACHOFEN-ECHT angegeben ist, mitunter von der nun tatsächlich eruierten Zahl der Briefe erheblich differiert. – 1589 – 2.1 Verzeichnis der SchreiberInnen von an HP gerichteten Briefen, wie sie bei Bachofen-Echt 546–570 verzeichnet sind, samt darüber hinausgehenden Ergänzungen Anzahl Identifi- der kations- Briefe nummer Namens- und Standesangabe nach BACHOFEN-ECHT bei der Bach- Person ofen- Echt 1 Abdul Hassan, Arabische Briefe 5 2 Abdul Medschid, Sultan, 1839-1861 1 3 Aberdeen G. Hamilton Campbell Earl of, englischer Gesandter in 3 Wien 4 Acerbi Josef Ritter von, k. k. Generalkonsul in in Ägypten 22 5 Ahmet Fethi Pascha, Großmeister der türkischen Artillerie 3 6 Acland Sir Thomas Dyke, Mitglied des englischen Parlamentes 65 7 Acland Leopold, Sohn des vorigen 3 8 Adelburg Edler von, Pera und Wien 5 9 Adelung Friedrich von, russischer Staatsrat 15 10 Aershen Baron (Wien) 1 11 Albani Giuseppe, Bischof von Bologna, Kardinal 1 12 Albarelli Theresa Vordoni, Padua, Verona, ohne Ortsangabe 5 13 Alexander I. -

The Lower Nobility in the Kingdom of Bohemia in the Early 15Th Century

| 73 The lower nobility in the Kingdom of Bohemia in the early 15 th century, based on the example of Jan Sádlo of Smilkov Silvie Van ēurova Preliminary communication UDK 177.6:32>(437.3)“14“ Abstract During the Hussite revolution, the lower nobility became an important, complex and powerful political force and exerted considerable influence over the Czech Kingdom. The life of Jan Sádlo of Smilkov is used as an example of a lower nobleman who, due to the political situation, was able to become an influential person and become involved in political developments prior to the revolution and in the revolution’s first year. The story of his life offers some possible interpretations of the events that may have impacted the lower nobility’s life at the beginning of 15 th century. Keywords : Lower nobility, Jan Sádlo of Smilkov, pre-Hussite period, Deeds of Complaint, Hussite revolution In the pre-Hussite period, the lower nobility represented a largely heterogeneous and also quite numerous class of medieval society. The influence of this social group on the growing crisis in the pre-Hussite period, its very involvement in the revolution and its in many regards not inconsiderable role during the Hussite Wars have been explored by several generations of historians thus far (Hole ēek 1979, 83-106; Polívka 1982b, Mezník 1987; Pla ēek 2008, Grant 2015). Yet new, unexplored issues still arise regarding the lower nobility’s property (Polívka 1978: 261-272, Jurok 2000: 63-64, Šmahel 2001: 230-242), its local position (Petrá Ÿ 1994: Mezník 1999: 129-137, 362-375; Mlate ēek 2004) and continuity, as well as kinship ties (Mlate ēek 2014) and its involvement in politics. -

Technology Fast 500

2001 Deloitte & Touche Technology Fast 500 www.fast500.com Leading the Way It’s been a tough year for the technology sector, and the com- Industry segments represented were relatively stable from panies on this year’s Deloitte & Touche Technology Fast 500 last year, with software companies again leading the way are not immune to the effects of the tech correction and the with 221 companies or 44 percent of the list. Notably, given slowing of the U.S. economy. Indeed, some Fast 500 compa- the malaise in the field, communications companies jumped nies have seen their businesses slow significantly in 2001 and from nine percent to 13 percent of the list.While Internet are struggling after five years of dramatic growth (the 2001 companies are prominent at the top of the list, as a group, Fast 500 measures five-year growth through fiscal 2000). they slid from 17 percent to 15 percent. With that said, this year’s Technology Fast 500 companies, as Geographical Shifts a group, found a way to grow even faster than their prede- After a one-year hiatus, the West resumed its position at the cessors.The 2001 Technology Fast 500 averaged a five-year head of the technology class, accounting for 32 percent of percentage revenue growth rate of 6,184 percent, compared the Fast 500, up from 27 percent. California was, by far, the to 3,956 percent for last year’s list.The top five companies biggest contributor to the list with 132 companies, including grew an average of 93,496 percent, compared to 59,367 percent two of the top three companies, calling the Golden State for last year’s top five. -

LIST of SECTION 13F SECURITIES ** PAGE 1 RUN TIME:09:57 Ivmool

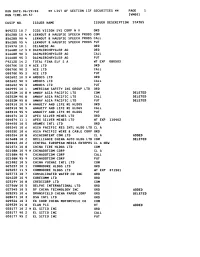

RUN DATE:06/29/00 ** LIST OF SECTION 13F SECURITIES ** PAGE 1 RUN TIME:09:57 IVMOOl CUSIP NO. ISSUER NAME ISSUER DESCRIPTION STATUS B49233 10 7 ICOS VISION SYS CORP N V ORD B5628B 10 4 * LERNOUT & HAUSPIE SPEECH PRODS COM B5628B 90 4 LERNOUT & HAUSPIE SPEECH PRODS CALL B5628B 95 4 LERNOUT 8 HAUSPIE SPEECH PRODS PUT D1497A 10 1 CELANESE AG ORD D1668R 12 3 * DAIMLERCHRYSLER AG ORD D1668R 90 3 DAIMLERCHRYSLER AG CALL D1668R 95 3 DAIMLERCHRYSLER AG PUT F9212D 14 2 TOTAL FINA ELF S A WT EXP 080503 G0070K 10 3 * ACE LTD ORD G0070K 90 3 ACE LTD CALL G0070K 95 3 ACE LTD PUT GO2602 10 3 * AMDOCS LTD ORD GO2602 90 3 AMDOCS LTD CALL GO2602 95 3 AMDOCS LTD PUT GO2995 10 1 AMERICAN SAFETY INS GROUP LTD ORD G0352M 10 8 * AMWAY ASIA PACIFIC LTD COM DELETED G0352M 90 8 AMWAY ASIA PACIFIC LTD CALL DELETED G0352M 95 8 AMWAY ASIA PACIFIC LTD PUT DELETED GO3910 10 9 * ANNUITY AND LIFE RE HLDGS ORD GO3910 90 9 ANNUITY AND LIFE RE HLDGS CALL GO3910 95 9 ANNUITY AND LIFE RE HLDGS PUT GO4074 10 3 APEX SILVER MINES LTD ORD GO4074 11 1 APEX SILVER MINES LTD WT EXP 110402 GO4450 10 5 ARAMEX INTL LTD ORD GO5345 10 6 ASIA PACIFIC RES INTL HLDG LTD CL A G0535E 10 6 ASIA PACIFIC WIRE & CABLE CORP ORD GO5354 10 8 ASIACONTENT COM LTD CL A ADDED G1368B 10 2 BRILLIANCE CHINA AUTO HLDG LTD COM DELETED 620045 20 2 CENTRAL EUROPEAN MEDIA ENTRPRS CL A NEW G2107X 10 8 CHINA TIRE HLDGS LTD COM G2108N 10 9 * CHINADOTCOM CORP CL A G2108N 90 9 CHINADOTCOM CORP CALL G2lO8N 95 9 CHINADOTCOM CORP PUT 621082 10 5 CHINA YUCHAI INTL LTD COM 623257 10 1 COMMODORE HLDGS LTD ORD 623257 11 -

1 UNITED STATES SECURITIES and EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C

1 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 13F FORM 13F COVER PAGE Report for the Calendar Year or Quarter Ended: September 30, 2000 Check here if Amendment [ ]; Amendment Number: This Amendment (Check only one.): [ ] is a restatement. [ ] adds new holdings entries Institutional Investment Manager Filing this Report: Name: AMERICAN INTERNATIONAL GROUP, INC. Address: 70 Pine Street New York, New York 10270 Form 13F File Number: 28-219 The Institutional Investment Manager filing this report and the person by whom it is signed represent that the person signing the report is authorized to submit it, that all information contained herein is true, correct and complete, and that it is understood that all required items, statements, schedules, lists, and tables, are considered integral parts of this form. Person Signing this Report on Behalf of Reporting Manager: Name: Edward E. Matthews Title: Vice Chairman -- Investments and Financial Services Phone: (212) 770-7000 Signature, Place, and Date of Signing: /s/ Edward E. Matthews New York, New York November 14, 2000 - ------------------------------- ------------------------ ----------------- (Signature) (City, State) (Date) Report Type (Check only one.): [X] 13F HOLDINGS REPORT. (Check if all holdings of this reporting manager are reported in this report.) [ ] 13F NOTICE. (Check if no holdings reported are in this report, and all holdings are reported in this report and a portion are reported by other reporting manager(s).) [ ] 13F COMBINATION REPORT. (Check -

§ 18. Impeachment of Judge Ritter

IMPEACHMENT POWERS Ch. 14 § 18 § 18. Impeachment of On June 1, 1933, the Committee Judge Ritter on the Judiciary reported House Resolution 163 (H. Rept. No. 191) Authorization of Investigation with committee amendments; the resolution was referred to the § 18.1 The Committee on the Committee of the Whole House on Judiciary reported in the 73d the state of the Union, since the Congress a resolution au- original resolution contained an thorizing an investigation appropriation.(21) into the conduct of Halsted On the same day, Hatton W. Ritter, a U.S. District Court Sumners, of Texas, Chairman of judge; the resolution was re- the Committee on the Judiciary, ferred to the Union Calendar asked unanimous consent to con- and considered and adopted sider House Resolution 163 in the in the House as in the Com- House as in the Committee of the mittee of the Whole by unani- Whole. The resolution and com- mous consent. mittee amendments read as fol- On May 29, 1933, Mr. J. Mark lows: Wilcox, of Florida, placed in the HOUSE RESOLUTION 163 hopper a resolution (H. Res. 163) authorizing the Committee on the Resolved, That the Committee on the Judiciary is authorized and directed, Judiciary to investigate the con- as a whole or by subcommittee, to in- duct of Halsted Ritter, District quire into and investigate the official Judge for the U.S. District Court conduct of Halsted L. Ritter, a district for the Southern District of Flor- judge for the United States District ida, to determine whether in the Court for the Southern District of Flor- opinion of the committee he had ida, to determine whether in the opin- been guilty of any high crime or ion of said committee he has been guilty of any high crime or mis- misdemeanor. -

Reflections on Scotland, the Caribbean and the Atlantic World, C

Morris, Michael (2013) Atlantic Archipelagos: A Cultural History of Scotland, the Caribbean and the Atlantic World, c.1740-1833. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/3863/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Atlantic Archipelagos: A Cultural History of Scotland, the Caribbean and the Atlantic World, c.1740-1833. Michael Morris Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Department of English Literature School of Critical Studies University of Glasgow September 2012 2 Abstract This thesis, situated between literature, history and memory studies participates in the modern recovery of the long-obscured relations between Scotland and the Caribbean. I develop the suggestion that the Caribbean represents a forgotten lieu de mémoire where Scotland might fruitfully ‘displace’ itself. Thus it examines texts from the Enlightenment to Romantic eras in their historical context and draws out their implications for modern national, multicultural, postcolonial concerns. Theoretically it employs a ‘transnational’ Atlantic Studies perspective that intersects with issues around creolisation, memory studies, and British ‘Four Nations’ history. -

List of Section 13F Securities, Third Quarter 2001

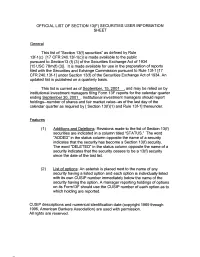

OFFICIAL LIST OF SECTION 13(F) SECURITIES USER INFORMATION SHEET General This list of "Section 13(f) securities" as defined by Rule 13f-I(c) [I7 CFR 240.13f-I (c)] is made available to the public pursuant to Section13 (f) (3) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 [I5 USC 78m(f) (3)]. It is made available for use in the preparation of reports filed with the Securities and Exhange Commission pursuant to Rule 13f-1 117 CFR 240.1 3f-I] under Section 13(f) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. An updated list is published on a quarterly basis. This list is current as of September, 15, 2001 ,and may be relied on by institutional investment managers filing Form 13F reports for the calendar quarter ending September 30, 2001 . Institutional investment managers should report holdings--number of shares and fair market value--as of the last day of the calendar quarter as required by [ Section 13(f)(l) and Rule 13f-I] thereunder. Features (1 ) Additions and Deletions: Revisions made to the list of Section 13(f) securities are indicated in a column titled "STATUS." The word "ADDED" in the status column opposite the name of a security indicates that the security has become a Section 13(f) security. The word "DELE-TED" in the status colurr~nopposite the name of a security indicates that the security ceases to be a 13(f) security since the date of the last list. (2) List of options: An asterisk is placed next to the name of any security having a listed option and each option is individually listed with its own CUSlP nurr~berimmediately below the name of the security having the option. -

Kathleen Beard Is Born August 10, 1908 in China • First Model T Produced by Ford • the Boy Emperor Pu Yi Is Chosen to Su

1908 Kathleen Beard is born August 10, 1908 in China First Model T produced by Ford The boy emperor Pu Yi is chosen to succeed the throne by the Empress Dowager. He was forced to abdicate in 1912 but was allowed to remain in the Forbidden City until 1924. Flora is 39 and teaching in Foochow, China Willard is 43, Ellen- 40, Phebe- 13, Gould- 12, Geraldine- 10, Dorothy- 7, Marjorie- 2, and Kathleen an infant. [This letter dated Feb. 2, 1908 was written from Foochow, China by Willard to his sister, Elizabeth. It is Chinese New Years and there have been many fire crackers going off all night. Sister, Flora, went on a five day houseboat trip. Small pox and measles are prevalent and they were all vaccinated that week. Letter donated to Yale by family in 2006.] Foochow, China Feb. 2nd 1908. My dear Elizabeth:- I‟m beginning this letter tonight almost sure that letters from you all are lying over in the P.O. But you will know that I am writing before being punched up. Today is the first day of the Chinese New Year. Every thing is quiet,- it was not quiet last night. Fire crackers were banging all night long- worse than in an American city where no restrictions are put on the small boy at Fourth of July. Every one is in his best and brightest. Flora walked over to the Y.M.C.A. with me this afternoon and she was much struck with the gorgeous head gear, coats, trousers, shoes, and trinkets she saw on people of all ages. -

3Rd Quarter, 2000

RUN DATE:10/06/00 ** LIST OF SECTION 13F SECURITIES ** PAGE 1 RUN TIME:14:34 IVMOOl CUSIP NO. ISSUER NAME ISSUER DESCRIPTION STATUS B49233 10 7 ICOS VISION SYS CORP N V ORD B5628B 10 4 * LERNOUT & HAUSPIE SPEECH PRODS COM B5628B 90 4 LERNOUT & HAUSPIE SPEECH PRODS CALL B5628B 95 4 LERNOUT & HAUSPIE SPEECH PRODS PUT D1497A 10 1 CELANESE AG ORD D1668R 12 3 * DAIMLERCHRYSLER AG ORD D1668R 90 3 DAIMLERCHRYSLER AG CALL D1668R 95 3 DAIMLERCHRYSLER AG PUT F9212D 14 2 TOTAL FINA ELF S A WT EXP 080503 G0070K 10 3 * ACE LTD ORD G0070K 90 3 ACE LTD CALL G0070K 95 3 ACE LTD PUT GO2602 10 3 * AMDOCS LTD ORD GO2602 90 3 AMDOCS LTD CALL GO2602 95 3 AMDOCS LTD PUT GO2995 10 1 AMERICAN SAFETY INS GROUP LTD ORD GO3910 10 9 * ANNUITY AND LIFE RE HLDGS ORD GO3910 90 9 ANNUITY AND LIFE RE HLDGS CALL GO3910 95 9 ANNUITY AND LIFE RE HLDGS PUT GO4074 10 3 APEX SILVER MINES LTD ORD GO4074 11 1 APEX SILVER MINES LTD WT EXP 110402 GO4397 10 8 * APW LTD COM ADDED GO4397 90 8 APW LTD CALL ADDED GO4397 95 8 APW LTD PUT ADDED GO4450 10 5 ARAMEX INTL LTD ORD GO5345 10 6 ASIA PACIFIC RES INTL HLDG LTD CL A G0535E 10 6 ASIA PACIFIC WIRE & CABLE CORP ORD GO5354 10 8 ASIACONTENT COM LTD CL A 620045 20 2 CENTRAL EUROPEAN MEDIA ENTRPRS CL A NEW G2107X 10 8 CHINA TIRE HLDGS LTD COM G2108N 10 9 * CHINADOTCOM CORP CL A G2108N 90 9 CHINADOTCOM CORP CALL G2108N 95 9 CHINADOTCOM CORP PUT 621082 10 5 CHINA YUCHAI INTL LTD COM 623257 10 1 COMMODORE HLDGS LTD ORD 623257 11 9 COMMODORE HLDGS LTD WT EXP 071501 623773 10 7 CONSOLIDATED WATER CO INC ORD G2422R 10 9 * CORECOMM LTD ORD G2422R 90 9 CORECOMM LTD CALL G2422R 95 9 CORECOMM LTD PUT G2519Y 10 8 CREDICORP LTD COM G2706W 10 5 DELPHI INTERNATIONAL LTD ORD 627545 10 5 DF CHINA TECHNOLOGY INC ORD G2759W 10 1 DIGITAL UNITED HOLDINGS LTD ORD ADDED 628471 10 3 DSG INTL LTD ORD 629526 10 3 EK CHOR CHINA MOTORCYCLE CO COM 629539 14 8 ELAN PLC R T 630177 10 2 * EL SIT10 INC ORD 630177 90 2 EL SIT10 INC CALL RUN DATE:10/06/00 ** LIST OF SECTION 13F SECURITIES ** PAGE 2 RUN TIME:14:34 IVMOOl CUSIP NO.