Reflections on Scotland, the Caribbean and the Atlantic World, C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

After the Treaties: a Social, Economic and Demographic History of Maroon Society in Jamaica, 1739-1842

University of Southampton Research Repository Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis and, where applicable, any accompanying data are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis and the accompanying data cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content of the thesis and accompanying research data (where applicable) must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder/s. When referring to this thesis and any accompanying data, full bibliographic details must be given, e.g. Thesis: Author (Year of Submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University Faculty or School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. University of Southampton Department of History After the Treaties: A Social, Economic and Demographic History of Maroon Society in Jamaica, 1739-1842 Michael Sivapragasam A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History June 2018 i ii UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY Doctor of Philosophy After the Treaties: A Social, Economic and Demographic History of Maroon Society in Jamaica, 1739-1842 Michael Sivapragasam This study is built on an investigation of a large number of archival sources, but in particular the Journals and Votes of the House of the Assembly of Jamaica, drawn from resources in Britain and Jamaica. Using data drawn from these primary sources, I assess how the Maroons of Jamaica forged an identity for themselves in the century under slavery following the peace treaties of 1739 and 1740. -

ROBERT BURNS and PASTORAL This Page Intentionally Left Blank Robert Burns and Pastoral

ROBERT BURNS AND PASTORAL This page intentionally left blank Robert Burns and Pastoral Poetry and Improvement in Late Eighteenth-Century Scotland NIGEL LEASK 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX26DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York # Nigel Leask 2010 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available Typeset by SPI Publisher Services, Pondicherry, India Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by MPG Books Group, Bodmin and King’s Lynn ISBN 978–0–19–957261–8 13579108642 In Memory of Joseph Macleod (1903–84), poet and broadcaster This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgements This book has been of long gestation. -

Ethical Record the Proceedings of the South Place Ethical Society

Ethical Record The Proceedings of the South Place Ethical Society Vol. 107 No. 1 £1.50 Jan-Feb, 2002 THE GENOCIDAL PRIMATE - A NOTE ON HOLOCAUST DAY When one sees how violent mankind has been, both to itself and to other species, it appears that, of the contemporary primate species, we have more in common with the spiteful meat-eating chimp than with the placid, vegetarian gorilla or the recently discovered, furiously promiscuous bonobo chimp. Our ancestors probably wiped out the Neanderthals in the course of their territorial disputes and with the final triumph of homo 'sapiens', rationalisations for genocide began to be invented (see the terrible 1 Sam. 15.3). Science tells us that human behaviour is the outcome of influences working throughout life on a plastic, gene-filled embryo. Now humanists are frequently expected, mistakenly in my view, to have faith in the natural goodness and inevitable progress of mankind. It would be more accurate however to believe in neither goodness nor evil as innate, embodied qualities. To be a humanist, it is sufficient to realise that we are each bound to justify our actions ourselves and, in strict logic, cannot defer our morality to any authority, real or imagined. The complicity of religious authorities in permitting agents of the Nazi genocidal machine to bear the 'Gott mit uns' (God is with Us) badge should be seen as an indelible blot on the ecclesiastical record. Death- camp inmates did well to ask 'Where is our God?' as their co-religionists choked in their Zyklon B 'showers'. To preserve the sentimental notion of a just God, some 'holocaust theologians' even stoop to blaming the victims. -

Msps with Dual Mandates

MSPs with Dual Mandates Session 5 (5 May 2016 to date) MSPs in Session 5 who were also MPs Name of MSP Party MSP for MP for Additional Notes Douglas Ross Con Highlands and Islands Moray Elected in the general election on 8 June 2017. Resigned as an MSP 11 June 2017. Ross Thomson Con North East Scotland Aberdeen South Elected in the general election on 8 June 2017. Resigned as an MSP 12 June 2017. MSPs in Session 5 who are also Councillors Name of MSP Party MSP for Councillor for Additional Notes Tom Mason Con North East Scotland Midstocket/ Rosemount Appointed as MSP for North East Scotland on 15 June 2017. He replaced Ross Thomson who resigned on 12 June 2017. MSPs in Session 5 who were also Councillors Name of MSP Party MSP for Councillor for Additional Notes Jeremy Balfour Con Lothian Corstorphine/Murrayfield Resigned as a Councillor 4 May 2017. Michelle Ballantyne Con South Scotland Selkirkshire Resigned as a Councillor 30 November 2017. She became the regional member for the Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party for South Scotland on 17 May 2017. She replaced Rachael Hamilton who resigned on 2 May 2017. Finlay Carson Con Galloway and West Dumfries Castle Douglas and Glenrothes Resigned as a Councillor 4 May 2017. Maurice Cory Con West Scotland Lomond North Resigned as a Councillor 4 May 2017. Page 1 of 8 MSPs with Dual Mandates Mairi Gougeon SNP Angus North and Mearns Brechin and Edzell Elected as Mairi Evans. Resigned as a Councillor 4 May 2017. Monica Lennon Lab Central Scotland Hamilton North and East Resigned as a Councillor 4 May 2017. -

Economics of Slavery Essay

1 From: The Oxford Handbook of Slavery in the Americas, ed. Robert L. Paquette and Mark M. Smith (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2010) The Economics of Slavery Peter A. Coclanis Writing on the economics of slavery is in some ways an impossibly difficult task, for the subject’s limits and bounds are viewed by many as virtually coterminous with those of slavery itself. Indeed, such an assignment has become increasingly difficult over time, as economists incorporate more and more areas of human experience into their interpretive clutches. Whereas at one time almost everyone conceded the material realm to economics, but cordoned off spiritual concerns, economists now make claims on such concerns as well, bringing the emotions, the psyche, and even the soul under the discipline’s dominion. It is thus a long way from the ancient Greeks, whose original sense of economics concerned the rules, customs, and laws (nomos) of the house or household (oikos), to Nobelist Gary Becker, for whom the decision to bear children is interpretively akin to the decision to purchase a refrigerator or car, to more recent writers who have written on the economics of attention, interpreted the rise of religion and the origin of fear in economic terms, and linked behavioral expressions ranging from sexual orientation to laughter to cruelty to economic variables. 2 This said, here we shall focus on issues of traditional concern to economic historians of slavery, to wit: the origins of and motivations/rationales for slavery; pattern and variation in the institution both across space and over time; questions relating to slavery’s profitability; the developmental effects of slavery; and the reasons for its demise. -

Supplement to the BELFAST GAZETTE, Slst DECEMBER, 1983

1180 Supplement to THE BELFAST GAZETTE, SlST DECEMBER, 1983 David John COFFEY, Chief Wireless Technician, Police Authority, Northern Ireland. Samuel Cahoon COWAN, General Secretary, Ulster Savings Committee. ST. JAMES'S PALACE, LONDON, S.W.L Margaret Marilyn, Mrs. CRAIG, Vice President, Road 31st December 1983 Safety Council of Northern Ireland ; Member, RoSPA National Road Safety Committee. THE QUEEN has been graciously pleased to approve the Frederick DALY. For services to Golf. award of the British Empire Medal (Civil Division) to the undermentioned : Ivy Ethel Mary, Mrs. ELLIOTT, District Nurse, Florence- court, Co. Fermanagh. British Empire Medal Margaret Teresa, Mrs. GALLAGHER, Member, Police (Civil Division) Authority for Northern Ireland. Hugh Allen BLACK, Deputy Superintendent (Security William Aiken HAMILTON, Charge Nurse and Acting and Warders), Ulster Museum. Nursing Officer, Bannvale Hospital, Gilford, Co. Down. William Henry Gornal BLACK, lately Joiner, Lambeg William John HAMILTON, Chief Superintendent, Royal Industrial Research Association. Ulster Constabulary. Sydney BRIGGS, Ward Orderly, Daisy Hill Hospital, Michael Robert HENDRA, Member, Northern Ireland Newry. Paraplegic Association. Robert Charles BROWN, Messenger, Department of the William Stanley IRWIN, Chief Superintendent, Royal Environment. Northern Ireland. Ulster Constabulary. Samuel James GOURLEY, Repository Assistant I, Public Miss Margaret Helen JEFFREY, General Secretary, Sandes Record Office of Northern Ireland. Soldiers' and Airmen's Homes, Northern Ireland. Joseph Alexander McGORMAN, lately Senior Foreman, Miss Mary Elizabeth KENNEDY, Brigade Secretary, Ulster Sheltered Employment Ltd. Northern Ireland Division, the Girls' Brigade. Samuel McMULLAN, Senior Supervisor, Department of Miss Patricia MULHOLLAND. For services to the Irish Agriculture, Northern Ireland. Ballet Company. Samuel Frederick MARTIN. Sergeant, Royal Ulster Con- Fergus Anthony WHEELER. -

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

Lusardi 1999- Blackbeard Shipwreck Project with a Note on Unloading A

The Blackbeard Shipwreck Project, 1999: With a Note on Unloading a Cannon By: Wayne R. Lusardi NC Underwater Archaeological Conservation Laboratory Institute of Marine Sciences 3431 Arendell Street Morehead City, North Carolina 28557 Lusardi ii Table of Contents Introduction..........................................................................................................................................1 1999 Field Season.................................................................................................................................1 Figure 1: Two small cast-iron cannons during removal of concretion and associated ballast stones. ...................................................................................................................................1 The Artifacts .........................................................................................................................................2 Ship Parts and Equipment...................................................................................................................2 Arms...................................................................................................................................................2 Figure 2: Weight marks on breech of cannon C-21..............................................................3 Figure 3: Contents of cannon C-19 included three iron drift pins, a solid round shot and three wads of cordage.........................................................................................................3 -

Disingenuous Information About Clan Mactavish (The Clan Tavish Is an Ancient Highland Clan)

DISINGENUOUS INFORMATION ABOUT CLAN MACTAVISH (THE CLAN TAVISH IS AN ANCIENT HIGHLAND CLAN) BY PATRICK L. THOMPSON, CLAN MACTAVISH SEANNACHIE COPYRIGHT © 2018, PATRICK L. THOMPSON THIS DOCUMENT MAY NOT BE REPRODUCED, COPIED, OR STORED ON ANY OTHER SYSTEM WHATSOEVER, WITHOUT THE EXPRESSED WRITTEN PERMISSION OF THE AUTHOR. SANCTIONED CLAN MACTAVISH SOCIETIES OR THEIR MEMBERS MAY REPRODUCE AND USE THIS DOCUMENT WITHOUT PERMISSION OF THE AUTHOR. The more proper title of the clan is CLAN TAVISH (Scottish Gaelic: Clann Tamhais ), but it is commonly known as CLAN MACTAVISH (Scottish Gaelic: Clann MacTamhais ). The amount of disingenuous information found on the internet about Clan MacTavish is AMAZING! This document is meant to provide a clearer and truthful understanding of Clan MacTavish and its stature as recorded historically in Scotland. Certain statements/allegations made about Clan MacTavish will be addressed individually. Disingenuous statement 1: Thom(p)son is not MacTavish. That statement is extremely misleading. The Clans, Septs, and Regiments of the Scottish Highlands (CSRSH), 8th Edition, 1984, pp. 301, 554, Frank Adam, revised by Lord Lyon Sir Thomas Innes of Learney, states: pg. 111 Date of the 8th Edition of CSRSH is 1984, and pages 331 & 554 therein reflects that MacTavish is a clan, and that Thompson and Thomson are MacTavish septs. It does not say that ALL Thom(p)sons are of Clan MacTavish; as that would be a totally false assumption. Providing a reference footnote was the most expedient method to correct a long-held belief that MacTavish was a sept of Campbell, without reformatting the pages in this section. -

Claremen & Women in the Great War 1914-1918

Claremen & Women in The Great War 1914-1918 The following gives some of the Armies, Regiments and Corps that Claremen fought with in WW1, the battles and events they died in, those who became POW’s, those who had shell shock, some brothers who died, those shot at dawn, Clare politicians in WW1, Claremen courtmartialled, and the awards and medals won by Claremen and women. The people named below are those who partook in WW1 from Clare. They include those who died and those who survived. The names were mainly taken from the following records, books, websites and people: Peadar McNamara (PMcN), Keir McNamara, Tom Burnell’s Book ‘The Clare War Dead’ (TB), The In Flanders website, ‘The Men from North Clare’ Guss O’Halloran, findagrave website, ancestry.com, fold3.com, North Clare Soldiers in WW1 Website NCS, Joe O’Muircheartaigh, Brian Honan, Kilrush Men engaged in WW1 Website (KM), Dolores Murrihy, Eric Shaw, Claremen/Women who served in the Australian Imperial Forces during World War 1(AI), Claremen who served in the Canadian Forces in World War 1 (CI), British Army WWI Pension Records for Claremen in service. (Clare Library), Sharon Carberry, ‘Clare and the Great War’ by Joe Power, The Story of the RMF 1914-1918 by Martin Staunton, Booklet on Kilnasoolagh Church Newmarket on Fergus, Eddie Lough, Commonwealth War Grave Commission Burials in County Clare Graveyards (Clare Library), Mapping our Anzacs Website (MA), Kilkee Civic Trust KCT, Paddy Waldron, Daniel McCarthy’s Book ‘Ireland’s Banner County’ (DMC), The Clare Journal (CJ), The Saturday Record (SR), The Clare Champion, The Clare People, Charles E Glynn’s List of Kilrush Men in the Great War (C E Glynn), The nd 2 Munsters in France HS Jervis, The ‘History of the Royal Munster Fusiliers 1861 to 1922’ by Captain S. -

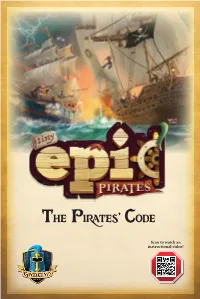

The Pirates' Code

The Pirates’ Code Scan to watch an instructional video! Components Legend Legend Legend Dread Legend Dread Dread Pirate Sure-fire Dread Pirate Sure-fire Pirate Sure-fire Pirate - Buccaneer Sure fire Buccaneer Buccaneer Buccaneer Swash 1 Market Mat Swash Buckler Swash Buckler Swash Buckler Buckler Corsair Corsair Corsair Corsair Pirate Pirate Pirate Pirate Sea Dog Sea Dog Sea Dog Repair Sea Dog Repair Repair Extort Repair Extort : Extort Cannons: Extort Cannons: Cannons: Rigging 1 Cannons Rigging 1 Rigging 1 1 Rigging 1 1 2 Port Tokens 1 1 4 Legend Mats 4 Helm Mats 16 Map Cards 8 8 6 6 6 4 4 4 2 2 2 1-4 1-4 1-3 1-3 1-3 1-2 1-2 1-2 . Cpt. Carmen RougeCpt Morgan Whitecloud FRONTS . Francisco de Guerra Cpt. Magnus BoltCpt BACKS 11 Merchant Cards 4 Double-Sided Captain Cards Alice O’Malice 1 Doc Blockley Lisa Legacy Sydney Sweetwater Buck Cannon Betty Blunderbuss Eliza Lucky Ursula Bane Willow Watch Taylor Truenorth Quartermaster Quigley Jolly Rodge Silent Seamus Lieutenant Flint Raina Rumor Black-Eyed Brutus Pale Pim 2 Salty Pete 2 Cutter Fang BACKS Sara Silver Jack “Fuse” Rogers Chopper Donovan Sally Suresight FRONTS Tina Trickshot 24 Crew Cards BACKS BACKS FRONTS 20 Search Tokens FRONTS 20 Order Tokens (5 in 4 colors) 2 4 Pirate Ships (in 4 colors) 2 Merchant Ships (in 2 colors) 1 Navy Ship 4 Captains (in 4 colors) 16 Deckhands 4 Legend Tokens 12 Treasures (4 in 4 colors) (in 4 colors) (3 in 4 colors) 1 Booty Bag 40 Booty Crates 4 Gold 3 Dice 12 Sure-fire Tokens (10 in 4 colors) Doubloons Prologue You helm a notorious pirate ship in the swashbuckling days of yore. -

The Construction of the Scottish Military Identity

RUINOUS PRIDE: THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE SCOTTISH MILITARY IDENTITY, 1745-1918 Calum Lister Matheson, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2011 APPROVED: Geoffrey Wawro, Major Professor Guy Chet, Committee Member Michael Leggiere, Committee Member Richard McCaslin, Chair of the Department of History James D. Meernik, Acting Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Matheson, Calum Lister. Ruinous pride: The construction of the Scottish military identity, 1745-1918. Master of Arts (History), August 2011, 120 pp., bibliography, 138 titles. Following the failed Jacobite Rebellion of 1745-46 many Highlanders fought for the British Army in the Seven Years War and American Revolutionary War. Although these soldiers were primarily motivated by economic considerations, their experiences were romanticized after Waterloo and helped to create a new, unified Scottish martial identity. This militaristic narrative, reinforced throughout the nineteenth century, explains why Scots fought and died in disproportionately large numbers during the First World War. Copyright 2011 by Calum Lister Matheson ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I: THE HIGHLAND WARRIOR MYTH ........................................................... 1 CHAPTER II: EIGHTEENTH CENTURY: THE BUTCHER‘S BILL ................................ 10 CHAPTER III: NINETEENTH CENTURY: THE THIN RED STREAK ............................ 44 CHAPTER IV: FIRST WORLD WAR: CULLODEN ON THE SOMME .......................... 68 CHAPTER V: THE GREAT WAR AND SCOTTISH MEMORY ................................... 102 BIBLIOGRAPHY ......................................................................................................... 112 iii CHAPTER I THE HIGHLAND WARRIOR MYTH Looking back over nearly a century, it is tempting to see the First World War as Britain‘s Armageddon. The tranquil peace of the Edwardian age was shattered as armies all over Europe marched into years of hellish destruction.